Weekly Insights 19 Aug 2022: GCC – on the path to fiscal sustainability?

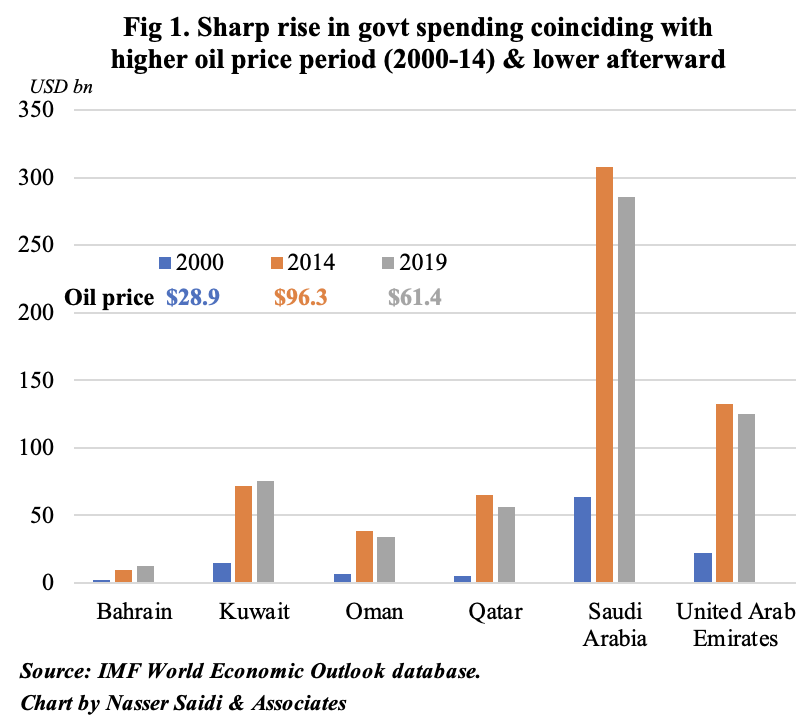

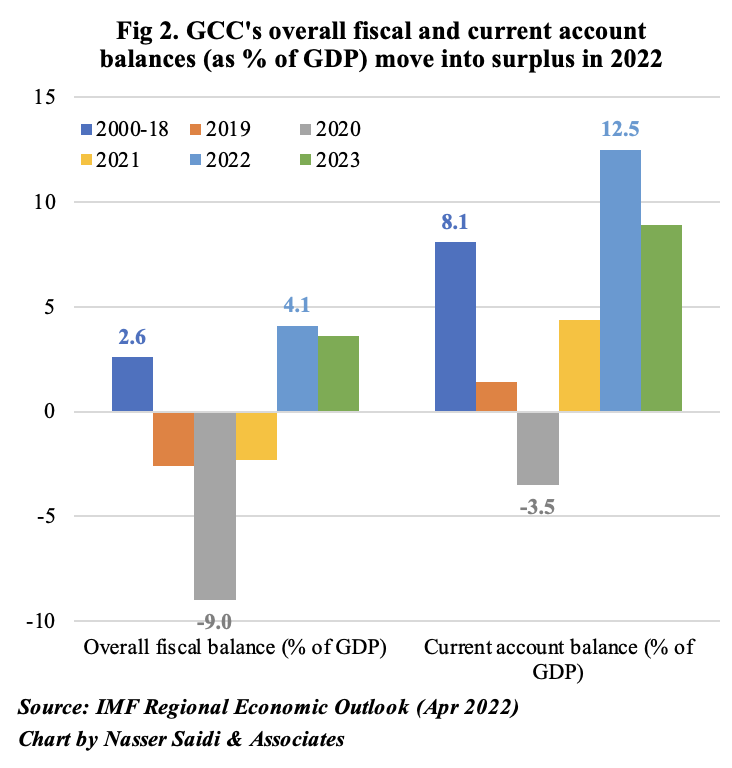

Many GCC nations have been practicing procyclical fiscal policies for decades i.e. spending would increase (or decrease) in boom (or recession) periods (in the context of oil market volatility). Higher oil prices led to increased government spending – most GCC nations saw spending grow around 5-fold between 2000 and 2019 (pre-Covid); in Qatar, it expanded ten-fold (see Fig 1).  It widened non-oil fiscal deficits (as % of non-oil GDP) but strengthened overall fiscal and external balances (see Fig 2). Following procyclicality in fiscal policy tends tohave near- and long-term implications: (a) a decline in spending would result in lower growth, in turn affecting the poorer segments of society more harshly (especially if social safety nets are minimal); (b) lower capital spending on long-gestation (productive) projects could negatively affect productivity growth and long-term growth prospects; and (c) lead to debt unsustainability. There has been a concerted effort towards fiscal consolidation in the past five years, with the most striking being non-oil revenue diversification efforts with the introduction of value added taxes and excise taxes.

It widened non-oil fiscal deficits (as % of non-oil GDP) but strengthened overall fiscal and external balances (see Fig 2). Following procyclicality in fiscal policy tends tohave near- and long-term implications: (a) a decline in spending would result in lower growth, in turn affecting the poorer segments of society more harshly (especially if social safety nets are minimal); (b) lower capital spending on long-gestation (productive) projects could negatively affect productivity growth and long-term growth prospects; and (c) lead to debt unsustainability. There has been a concerted effort towards fiscal consolidation in the past five years, with the most striking being non-oil revenue diversification efforts with the introduction of value added taxes and excise taxes.

Our Weekly Insights piece from last week showed evidence of a big shift this year, with oil producers shying away from a pro-cyclical fiscal policy stance, even as revenues surged thanks to higher oil prices. It is prudent to remember that 2020 was an exceptional year, with the GCC facing three simultaneous shocks – a slump in oil prices, dampened non-oil sector growth and increased Covid19 related spending. As a result, the GCC fiscal deficit as a percentage of GDP jumped to 9% in 2020 (2019:  1.8%) before falling to 1.1% in 2021 (Source: IMF). Oil and gas prices have recovered since then, with the windfall benefitting all oil and gas exporters to varying degrees, depending on the size of their exports and extent of subsidies of domestic consumption. Budget surpluses are being posted (estimated at more than 7% of GDP this year and next), but with no signs of fiscal slippage. Sound economic and fiscal policy recommends that revenue from windfalls, being temporary, should be saved, not spent. For now, this seems to be what governments are doing: spending levels are broadly in line with budget estimates (which were based on about USD 65 a barrel mark).

1.8%) before falling to 1.1% in 2021 (Source: IMF). Oil and gas prices have recovered since then, with the windfall benefitting all oil and gas exporters to varying degrees, depending on the size of their exports and extent of subsidies of domestic consumption. Budget surpluses are being posted (estimated at more than 7% of GDP this year and next), but with no signs of fiscal slippage. Sound economic and fiscal policy recommends that revenue from windfalls, being temporary, should be saved, not spent. For now, this seems to be what governments are doing: spending levels are broadly in line with budget estimates (which were based on about USD 65 a barrel mark).

With the recent uptick in inflationary pressure, some nations have announced food/ electricity/ subsidies and targeted safety nets: UAE and Saudi Arabia have extended financial support and also introduced price caps (on some food products, water, electricity, gasoline); Oman recently announced delaying plans to phase out its electricity subsidies (10 years instead of 5 previously).

Why is it different this time?

All policy indications and recent announcements are consistent with a commitment to fiscal discipline across the GCC, in order to maintain medium and long-term fiscal sustainability. The oil price shock of 2014-2015, Covid19 and the global intention to undertake an energy transition away from fossil fuels threatening the viability of dependence on oil and gas revenues, have all reinforced the commitment to fiscal discipline and economic diversification.

This is illustrated in the below:

- Increased diversification of the non-oil private sector: recent PMI readings indicate a strong recovery in the non-oil sector, boosted by strong domestic demand. In spite of the increase in input costs and output prices, confidence remains strong. This is in line with the ambitious Vision 2030 plans of Saudi Arabia, UAE’s emphasis on new sectors of growth (e.g. initiatives to boost industry/ manufacturing, FinTech/ Crypto, increasing non-oil exports with FTAs with at least 10 nations) and Qatar’s investments prior to the World Cup. This will tend to boost investor sentiment and support job creation in the private sector.

- Development of the local currency debt markets in many GCC nations adds to available funding options, in addition to the rollout of debt issuance laws. Borrowing to meet financial obligations will reduce the procyclicality of fiscal policy. The creation of government local currency debt markets,will enable corporates and financial institutions to issue local currency bonds and Sukuk, enabling the creation of a domestic yield and profit curves. Plans to refinance maturing debt instead of using revenue windfalls for repaying debt (as seen during the 2000-2008 oil price boom) will enhance fiscal sustainability. Even in Kuwait, where political deadlocks have delayed reform, there is a public debt law up for discussion (which would raise the debt ceiling and allow the nation to tap international markets).

- Diversification of the non-oil revenue base: most GCC nations have benefitted from increased revenue from taxes with the introduction of excise & value added taxes – 4 out of 6 GCC nations have implemented VAT. In Saudi Arabia, where VAT is highest at 15%, the share of tax revenues to non-oil GDP stood at 14.2% in 2021 (2020: 9.9%). There are signs of further reforms in this space with the GCC exploring new avenues of taxation be it UAE’s introduction of corporate tax from next year or Oman’s potential personal income taxes (for 2023).

- Efforts to increase privatisation, leading to capital market development: new listings of government-related enterprises (GREs) in the GCC are not only adding to the government coffers, but also opening sectors to private investment and participation, while additionally lowering risks of oil and gas becoming stranded assets. The listings of GREs will increase transparency (and overall governance) as well, given the regulatory requirement of financial disclosures.

- Addressing energy transition and net zero emissions commitments. Temperatures in the Middle East & Central Asia region have increased by 1.5 degrees Celsius in the past 3 decades (twice the global increase), and the IMF estimates that climate disasters could shave off 1-2 ppts from annual economic growth on a per capita basis. Hence adapting to climate change is an urgent need. The GCC’s NZE commitments support a drive to alternative sources of energy: this not only frees up oil and gas for export, but also leads to accumulation of foreign assets and international reserves, which can then be deployed for productive investment, including into renewable energy and decarbonisation.

But will the GCC hold steady… or will there be fiscal slippage?

As it stands, GCC countries will report both fiscal and external surpluses in 2022, and increase official reserves, all boosted by the windfall in oil revenues. However, there are looming risks and challenges:

- External and domestic risks. Potential tightening of global financial conditions along with monetary tightening by major countries (US, EU, UK), weaker-than-expected regional/ global economic recovery, uptick in inflation and related increase in subsidies, as well as public debt levels post-pandemic are some factors that may lead to slippage, especially if domestic reforms are unexpectedly delayed.

- Part of the windfall is being used to support ambitious megaprojects – this can be clearly seen in the case of Saudi Arabia. The ambitious plans of the Public Investment Fund and the National Development Fund expect investment spending to total about SAR 50bn and SAE 150bn annually. These could develop into a strain on the public sector balance sheet: so, regularly monitoring the activities of these entities is necessary to fully assess Saudi Arabia’s fiscal stance and position. (The example can be applied to any of the GCC nations in relation to their GREs.)

- Rapid growth of domestic debt markets: heavily indebted corporates and/ or GREs would be able to tap the markets to borrow more, creating potential contingent liabilities. FitchRatings estimates that aggregate GCC non-bank GRE debt rose to 37% of GDP in 2020 (an increase of 7 percentage points over 2019); though it has fallen in 2021, it remains much higher than pre-pandemic levels.

- Global monetary tightening. A period of lower oil prices from 2015 resulted in GCC average public debt levels rising from 24% of GDP in 2015 to 60% of GDP in 2021 while debt service burdens also grew (2021: 10%). Higher than expected interest payments due to global monetary tightening could become a potential burden. A tightening of financial conditions could increase borrowing costs, driving sovereign spreads higher, and be problematic for those with elevated debt levels (e.g. Bahrain).

- The rise in inflation rates has seen a subsequent increase in targeted subsidies / grants: financial support extended in the UAE and Saudi Arabia stand at USD 7.6bn and USD 5.33bn respectively. If these need to be extended due to persistent inflationary pressure, it might hamper reform efforts. Additionally, in the aftermath of Covid19, various programmes are in place to assist SMEs and start-ups in nations with higher unemployment rates: it remains to be seen what happens when support measures are phased out.

Concluding remarks

In the past, fiscal adjustments in the GCC have relied on expenditure cuts. But countries need to introduce growth enhancing fiscal reforms – e.g. current expenditure composition needs to be changed in the medium- to long-term (away from compensation of employees and subsidies). Already, there is an ongoing gradual reform of the long-standing social contract. In addition, the overall fiscal framework while allowing for deficit financing, should also focus on improving spending efficiency, along with the institution of fiscal rules for long-term fiscal sustainability.

Change will not happen overnight: oil will still be the main driver of growth so long as demand for oil remains strong. However, structural reforms – greater regional and international integration opening countries to domestic and foreign investment, , facilitating the establishment of business, liberalising residency requirements, improving indicators related to doing business and labour reforms among others – are needed to improve the non-oil private sector activity and are critical important for job creation, which is the policy imperative given the young demographics of the GCC countries.