“Global Economic Diversification Index 2024”, report released at the World Governments Summit, Feb 2024

“Global Economic Diversification Index 2024” was released by the Mohammed Bin Rashid School of Government (MBRSG) at the World Governments Summit held in Dubai on 12th Feb 2023. Dr. Nasser Saidi & Aathira Prasad were co-authors of the report, which was developed in cooperation with Keertana Subramani, Salma Refass and Fadi Salem (MBRSG) and Ben Shepherd (Developing Trade Consultants).

Access the latest and past reports as well as the underlying data on the website.

Economic diversification is a gradual, transformative process for countries that are dependent on commodities or a limited set of products or services.

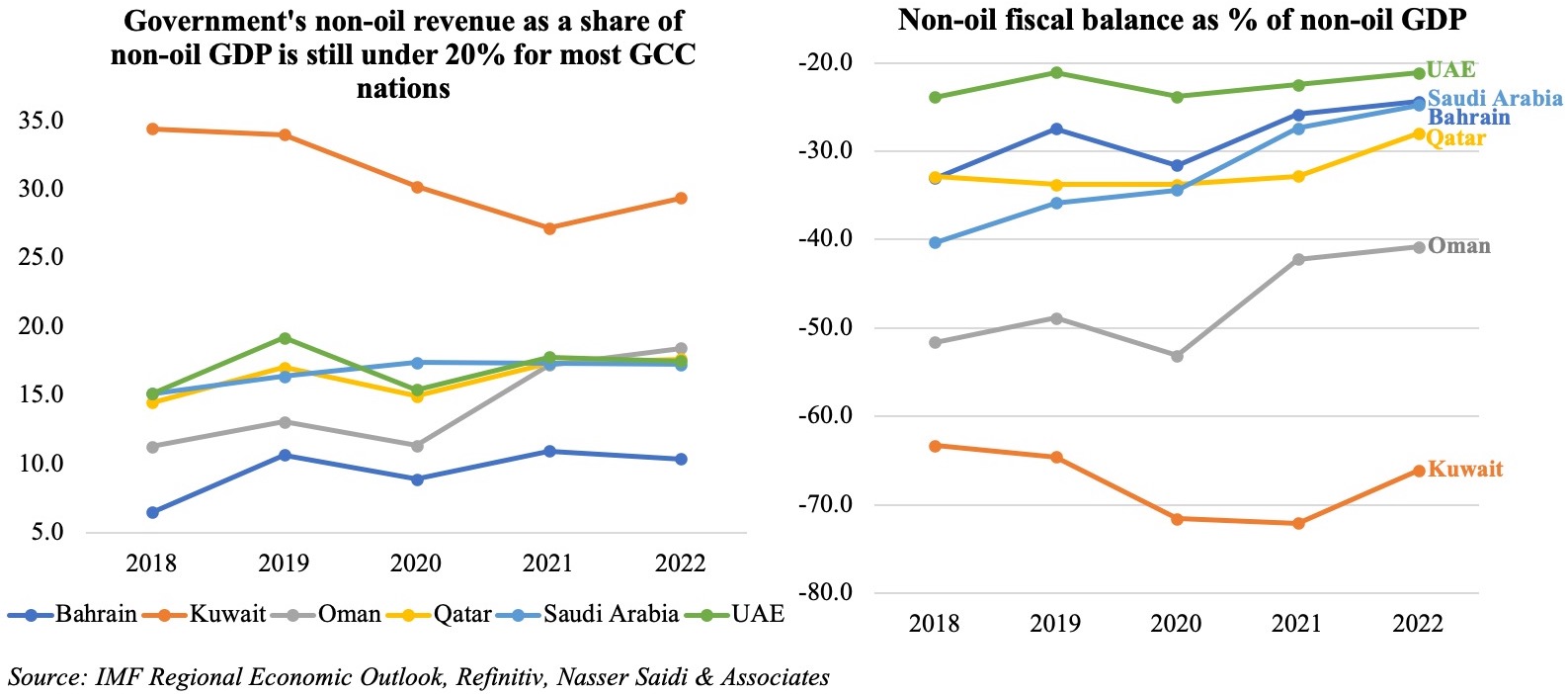

Diversification for commodity producers leads to greater macroeconomic stability, more sustainable growth patterns, enables a gradual move to higher value-added economic activities (from over-dependence on primary commodities) and helps lower trade concentration (i.e., increase a country’s ability to export a wider set of products to a larger set of trade partners). This requires active and productive private sector participation, and in parallel, governments need to rollout effective policy reforms (often structural) and undertake productive investments – while diversifying the government revenue base by raising non-commodity-related revenues.

The Global Economic Diversification Index (EDI), based on publicly available indicators, data and information,provides a quantitative measure of the state and evolution of the economic diversification of countries going back to 2000. The current edition expands the coverage of countries to a total of 112 countries (7 additional countries compared to the previous EDI edition) owing to improved data availability.

The United States, China and Germany retain the top 3 ranks in the EDI for 2022, with the top 10 nations having small margins between scores (implying the strength of diversification). Western European nations account for almost two-thirds of the top 20 highly-ranked nations and while 26 of the top 30 nations are high income, there are representatives from upper-middle income (China, Mexico, and Thailand) and one lower middle-income nation (India).

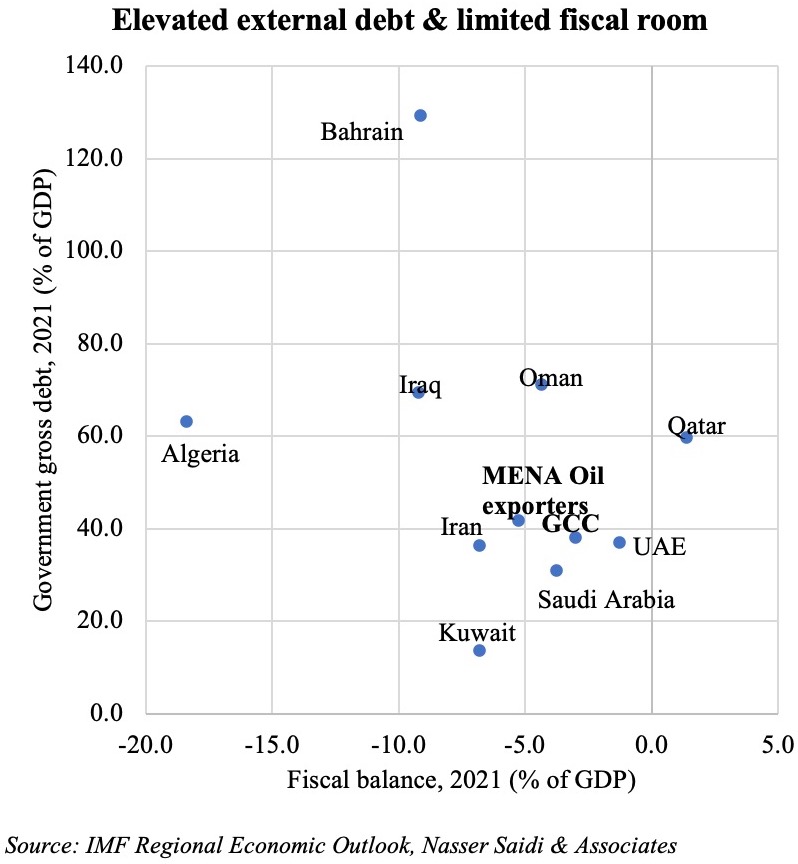

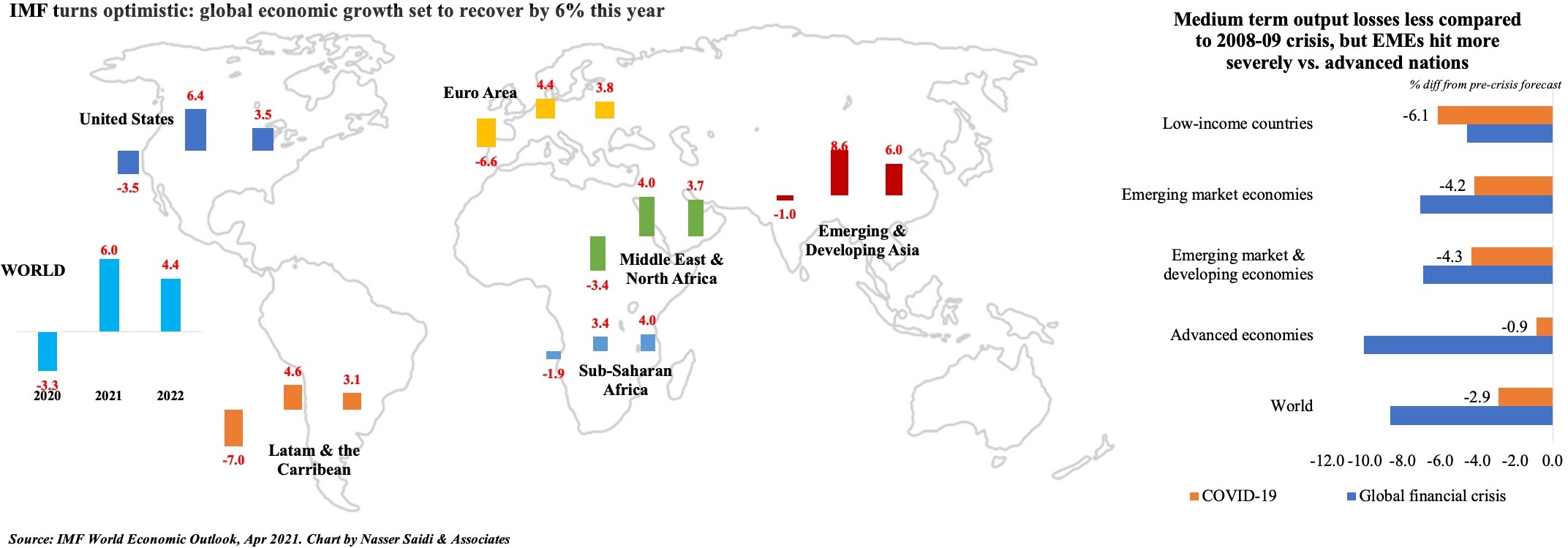

At the other end of the spectrum, however, the diversification process has been long and slow. Four nations – three from Sub-Saharan Africa alongside Kuwait from the Middle East and North Africa region (MENA) – continue to remain in the bottom 20 ranks of the EDI over the period. The share of MENA nations in the bottom 20 ranks fell to just 10% from one-fourth in 2000. At the same time, there were 13 Sub-Saharan African nations among the lowest 20-ranked nations in the year 2022 from nine in 2000. Furthermore, the catch up for lower ranked nations in the post-Covid era will be a tougher ask, given the long-term scarring effects and output loss induced by the pandemic in addition to an already limited fiscal space and existing debt burdens.

As the global economy slowly recovers post-pandemic, it is contending with a lasting structural change: the accelerated adoption of digital technologies, which has resulted in societal gains such as higher labour force participation rates and productivity gains among others (especially in nations where the basic infrastructure was already in place). Despite challenges in data availability in this realm, this edition of the EDI includes indicators that aim to capture the growth of the digital economy: three digital-specific indicators are added to the trade sub-index.

Using this updated list of indicators and availability of data, a revised trade+ (“trade-plus”) sub-index is calculated for the years 2010-2022, for a subset of 106 countries. The revised trade+ sub-index is also used to calculate a digital augmented EDI+ (“EDI-plus”) score and ranking. Other than the Sub-Saharan Africa region, all regional groups improved their trade+ sub-index scores in 2020-2022. While the top four ranked countries are the same in both the trade and trade+ sub-indices, of the bottom 20-ranked nations in the original trade sub-index, thirteen are worse-off when including digital indicators. This finding is in line with what other studies have shown i.e. if adoption is delayed, existing digital divides can widen leading to deteriorating outcomes and prospects in the absence of an acceleration of reforms. South Asia shows a significant upwards jump in trade+ scores over time and this is reflected as well in the EDI+ scores as well.

A clear outcome across countries is that digital economy investments improve trade diversification, notably through the ability to export services. For commodity producers and exporters, the report finds that they can strongly improve their overall EDI and trade rankings by investment in and adoption of new digital technology and its services. Additionally, country geographical size does not appear to be an impediment to economic diversification and EDI scores (e.g. highly-ranked nations such as Singapore, Ireland and Netherlands among others are relatively small economies, both in the EDI and EDI+ versions).

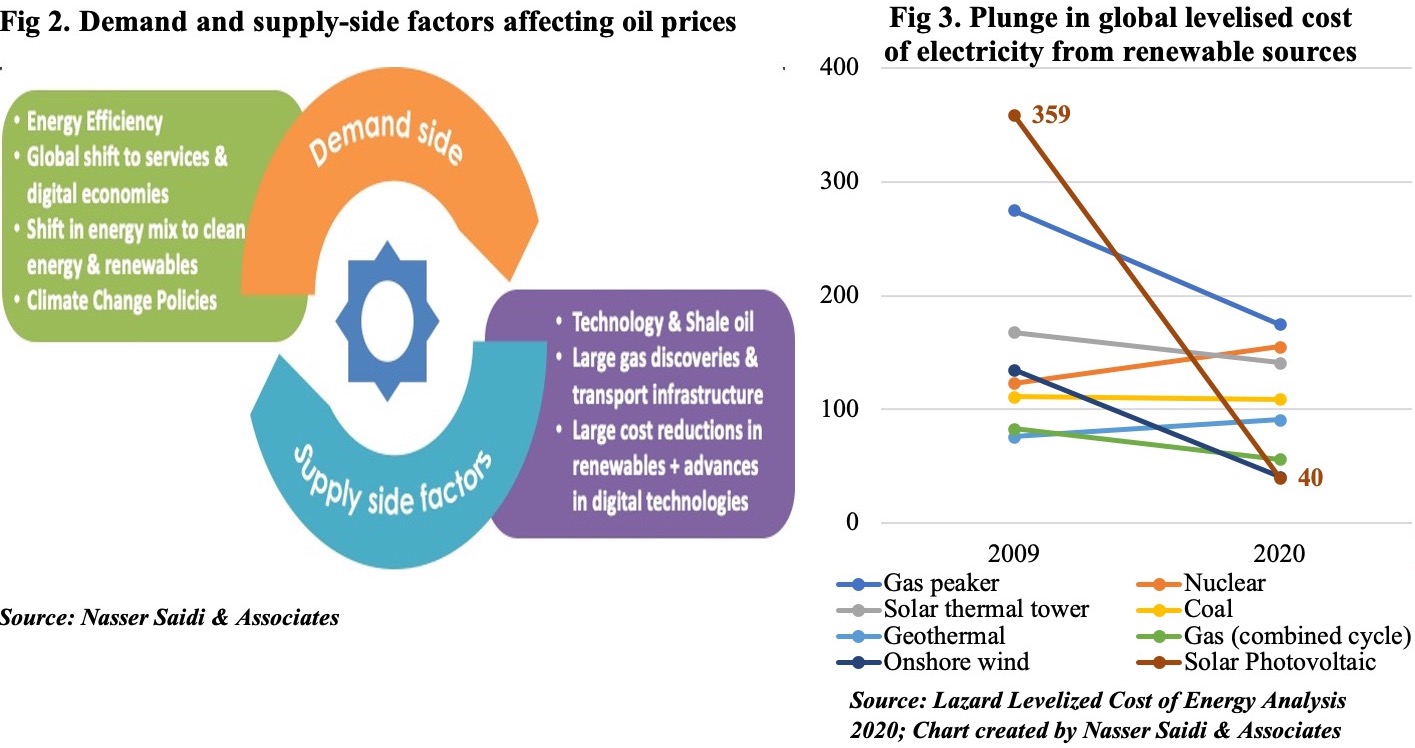

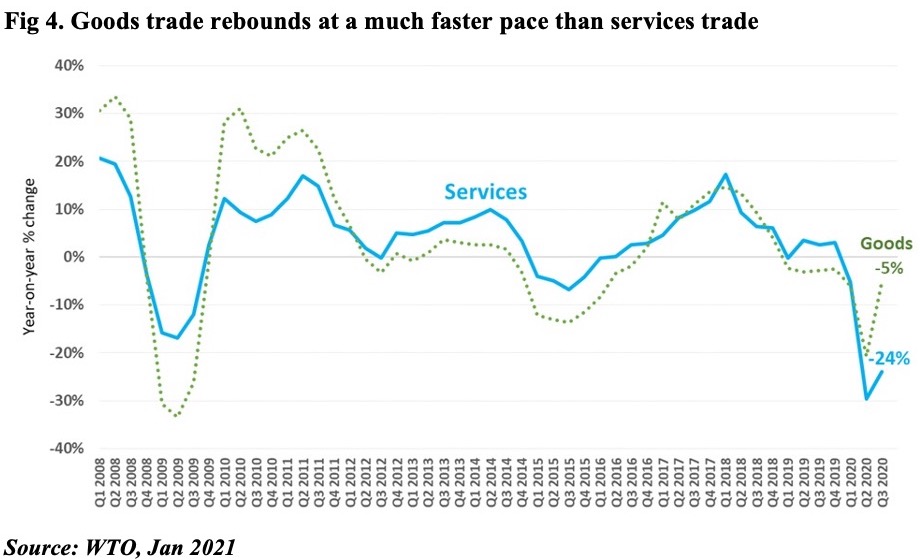

Commodity producing nations are vulnerable to volatility in commodity prices. Prices can be more or less volatile depending on the type of commodity. For instance, price of oil has been more volatile than the price of copper, wheat or cotton and other commodities, as shown by historical data. In the EDI sample of countries, more than 50% of the commodity dependent nations are reliant on fuels. The demand and supply shocks that occurred during the pandemic and those caused by ongoing wars, in addition to the planned energy transition to Net-Zero Emissions, increase the urgency for fossil fuel exporters to diversify – else these nations run the risk of being left with lower valued or stranded assets.

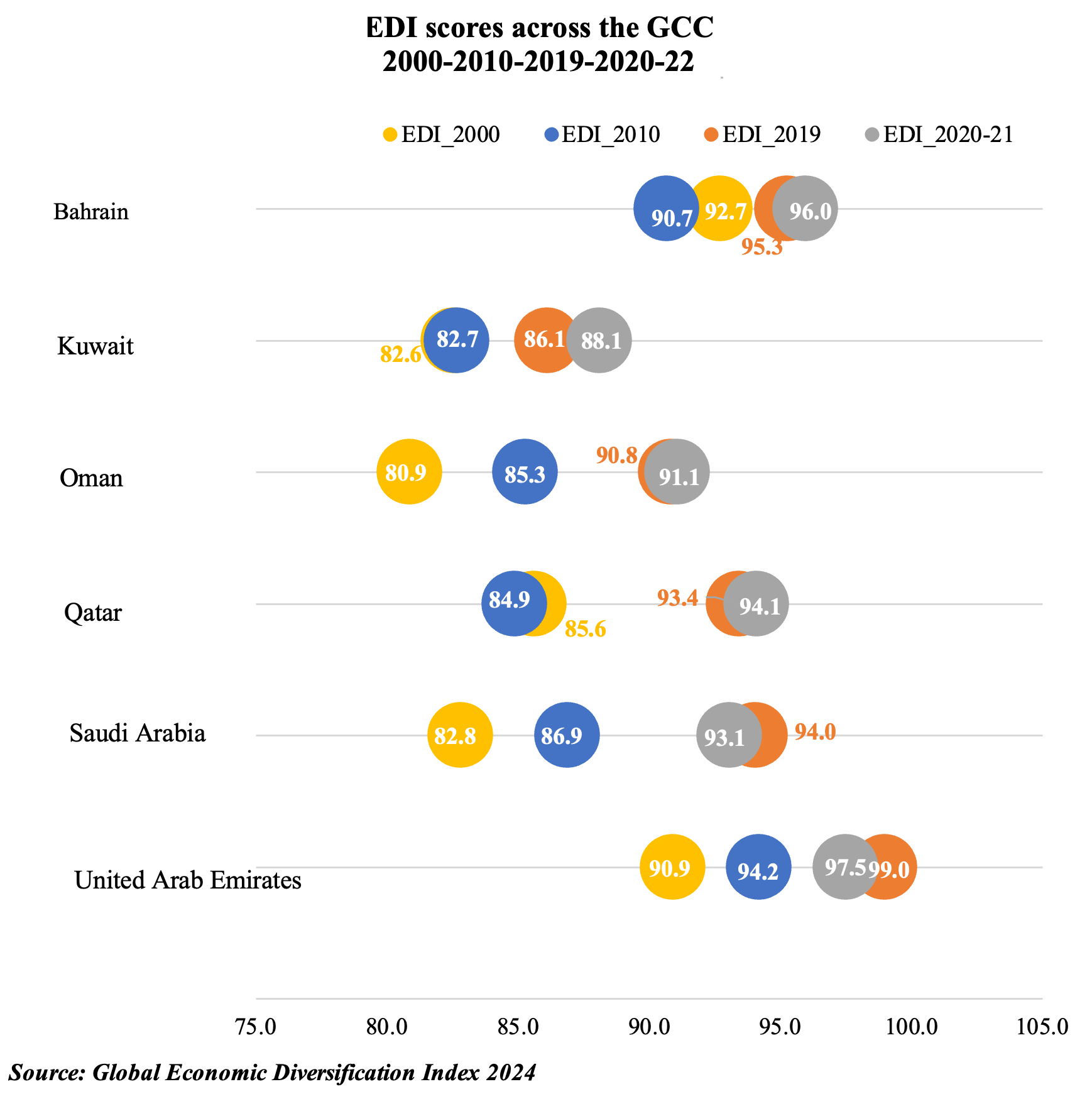

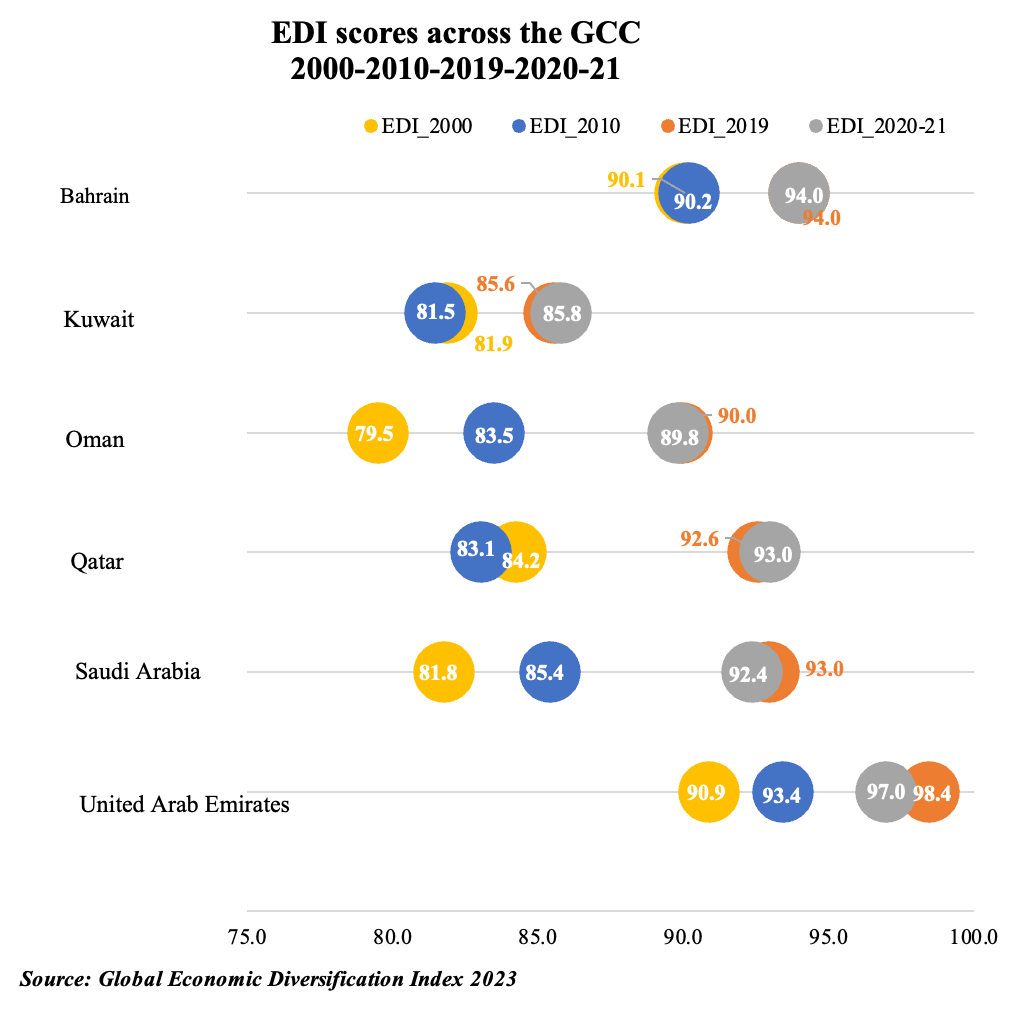

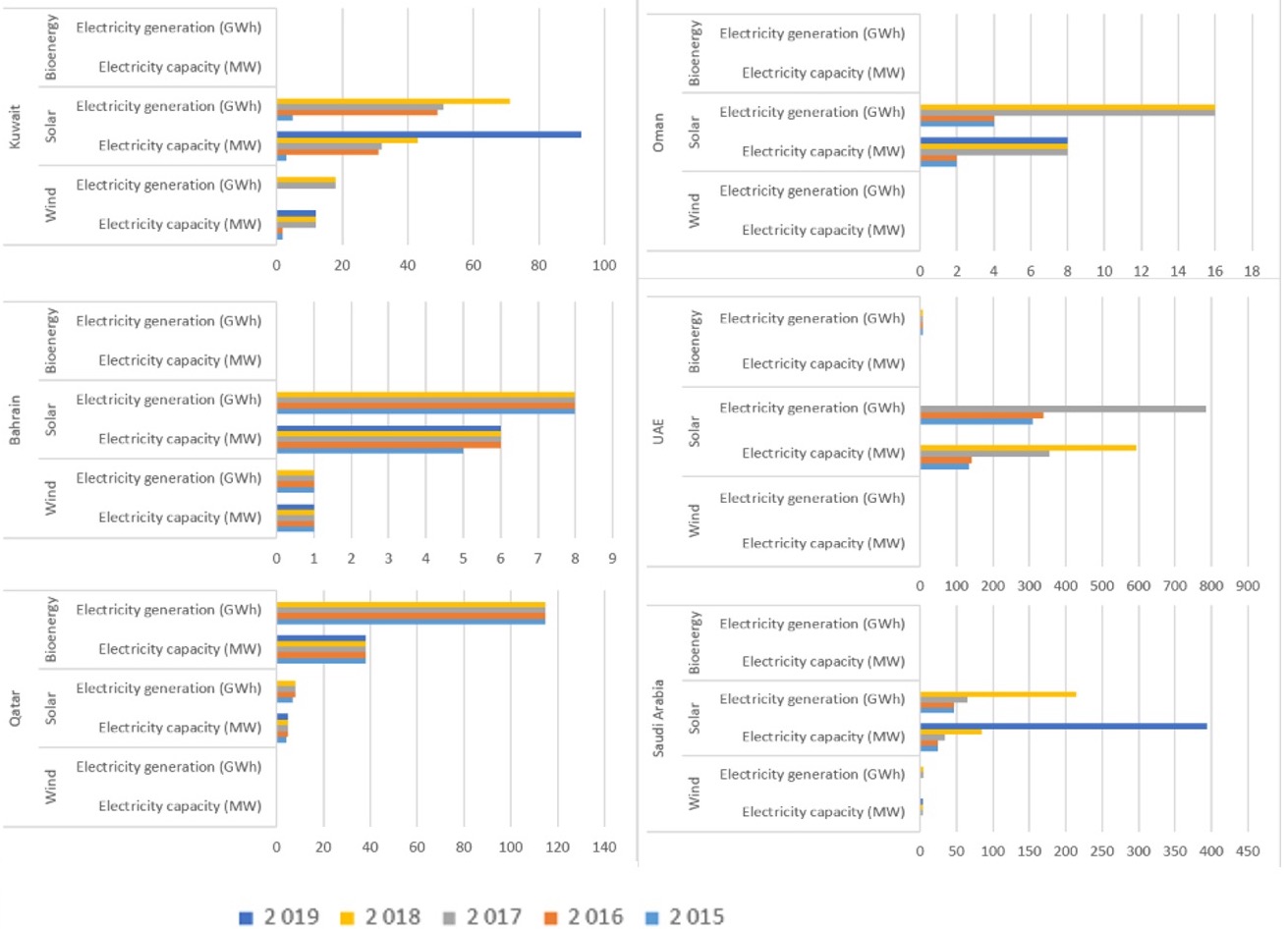

Sub-Saharan Africa’s commodity exporters posted the lowest EDI scores over time, with the 2020-2022 average score falling below the 2012-2015 period, underscoring not only the pandemic’s  negative impact on performance but also the divergent paces of recovery. However, both the MENA and Eastern Europe & Central Asia regions reported a slight improvement in the 2020-2022 period versus pre-pandemic scores: these nations were all fuel exporters (i.e. not exporters of any other commodities). The report also finds that countries that reduced (increased) the share of resource rents have seen an increase (decline) in EDI scores, but the relation is one of correlation and not causation. Among the GCC, UAE and Bahrain have higher EDI scores compared to their peers, while Saudi Arabia and Oman have both gained over 10-points in 2020-2022 compared to their EDI score in 2000. Improvements in GCC scores have resulted from the implementation of reforms at a much more aggressive pace after the pandemic – including incentives to invest in new tech sectors, plans to broaden tax bases, trade liberalisation through free trade agreements and improvements to regulatory and business environment among others facilitating rights of establishment and labour mobility – that support diversification efforts and provide long-term economic resilience.

negative impact on performance but also the divergent paces of recovery. However, both the MENA and Eastern Europe & Central Asia regions reported a slight improvement in the 2020-2022 period versus pre-pandemic scores: these nations were all fuel exporters (i.e. not exporters of any other commodities). The report also finds that countries that reduced (increased) the share of resource rents have seen an increase (decline) in EDI scores, but the relation is one of correlation and not causation. Among the GCC, UAE and Bahrain have higher EDI scores compared to their peers, while Saudi Arabia and Oman have both gained over 10-points in 2020-2022 compared to their EDI score in 2000. Improvements in GCC scores have resulted from the implementation of reforms at a much more aggressive pace after the pandemic – including incentives to invest in new tech sectors, plans to broaden tax bases, trade liberalisation through free trade agreements and improvements to regulatory and business environment among others facilitating rights of establishment and labour mobility – that support diversification efforts and provide long-term economic resilience.

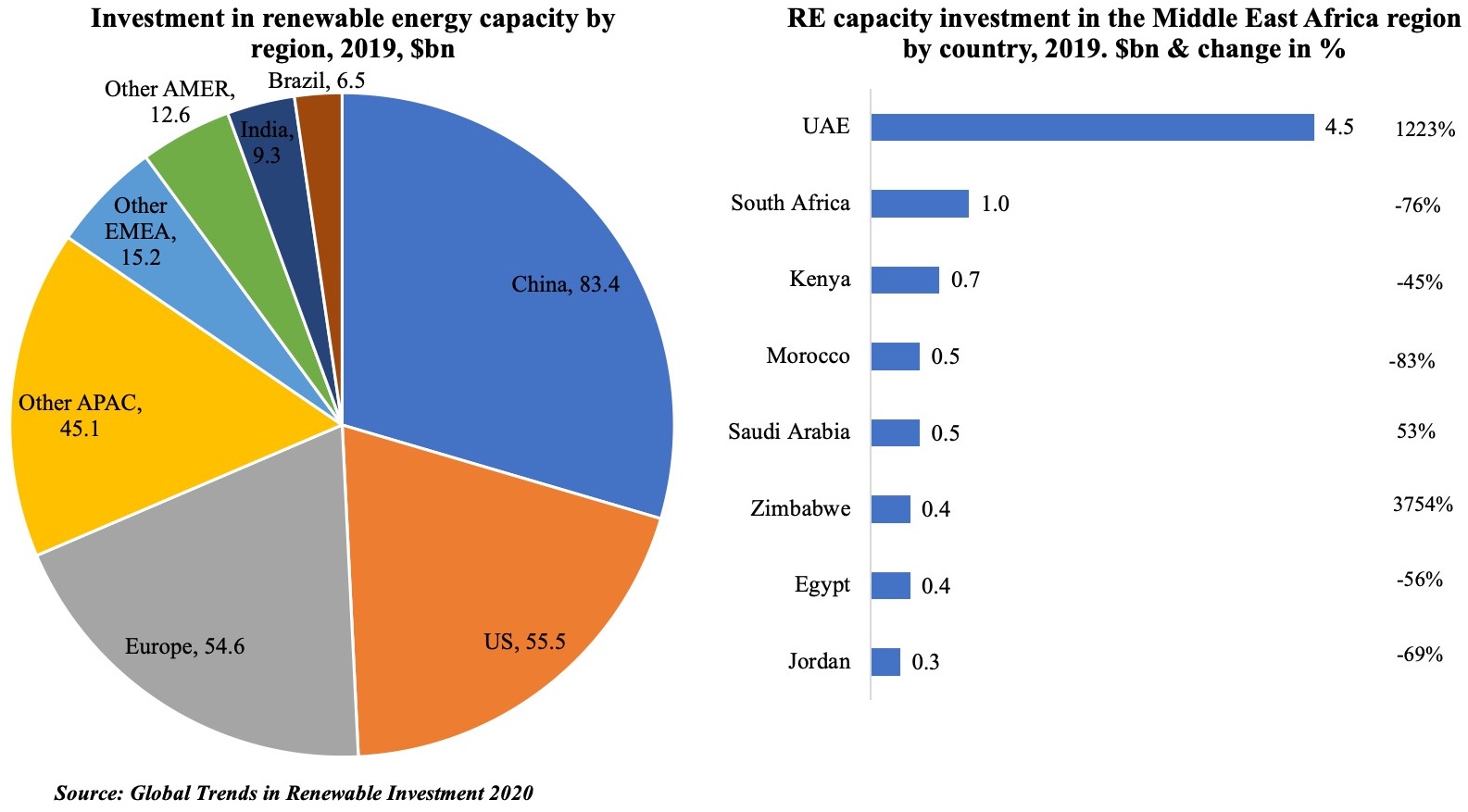

Lastly, the report highlights an increasingly relevant discussion related to climate change and the vulnerability of commodity-dependent nations. As countries adapt to and mitigate climate change risks, energy transition and “Green economy” investments, such as renewable energy, can play a key role in transforming economies and output structures. Fossil fuels are likely to remain in the global energy mix for decades, but a potential sustained decline in demand necessitates the roll-out of diversification policies at the earliest. With many oil-exporting nations in the Middle East already diversifying energy sources, potential export of clean energy from these nations could widen their export base (both in terms of products and trade partners). Furthermore, regional integration would aid diversification efforts of commodity producers and also provide a massive opportunity to link with domestic or regional value chains, adding to diversification efforts.

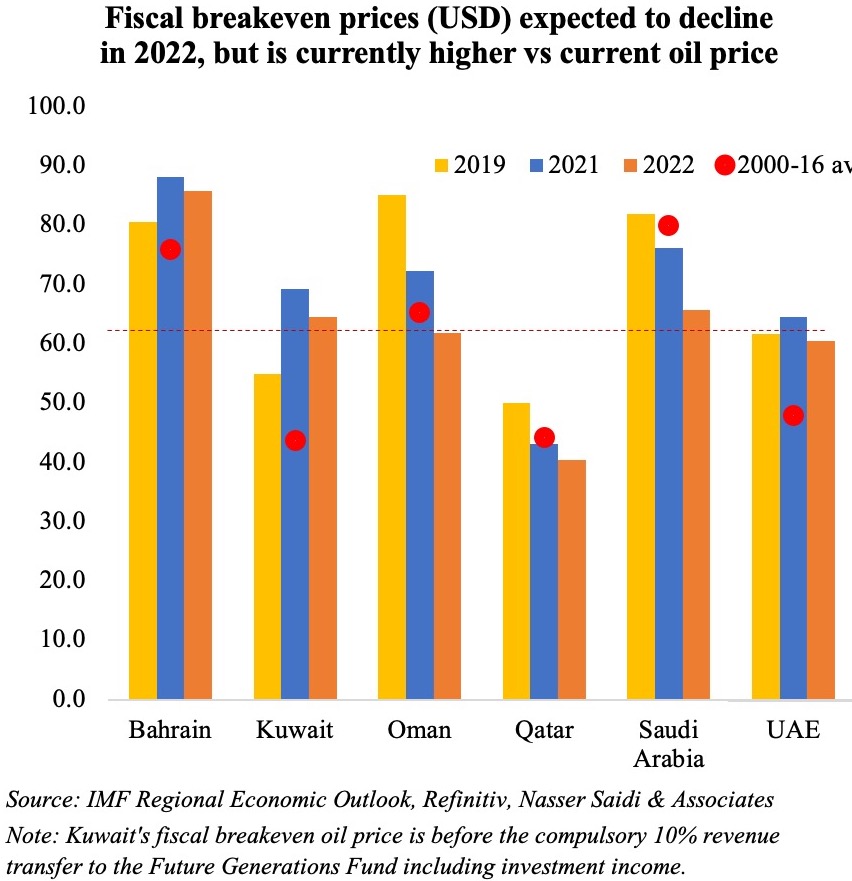

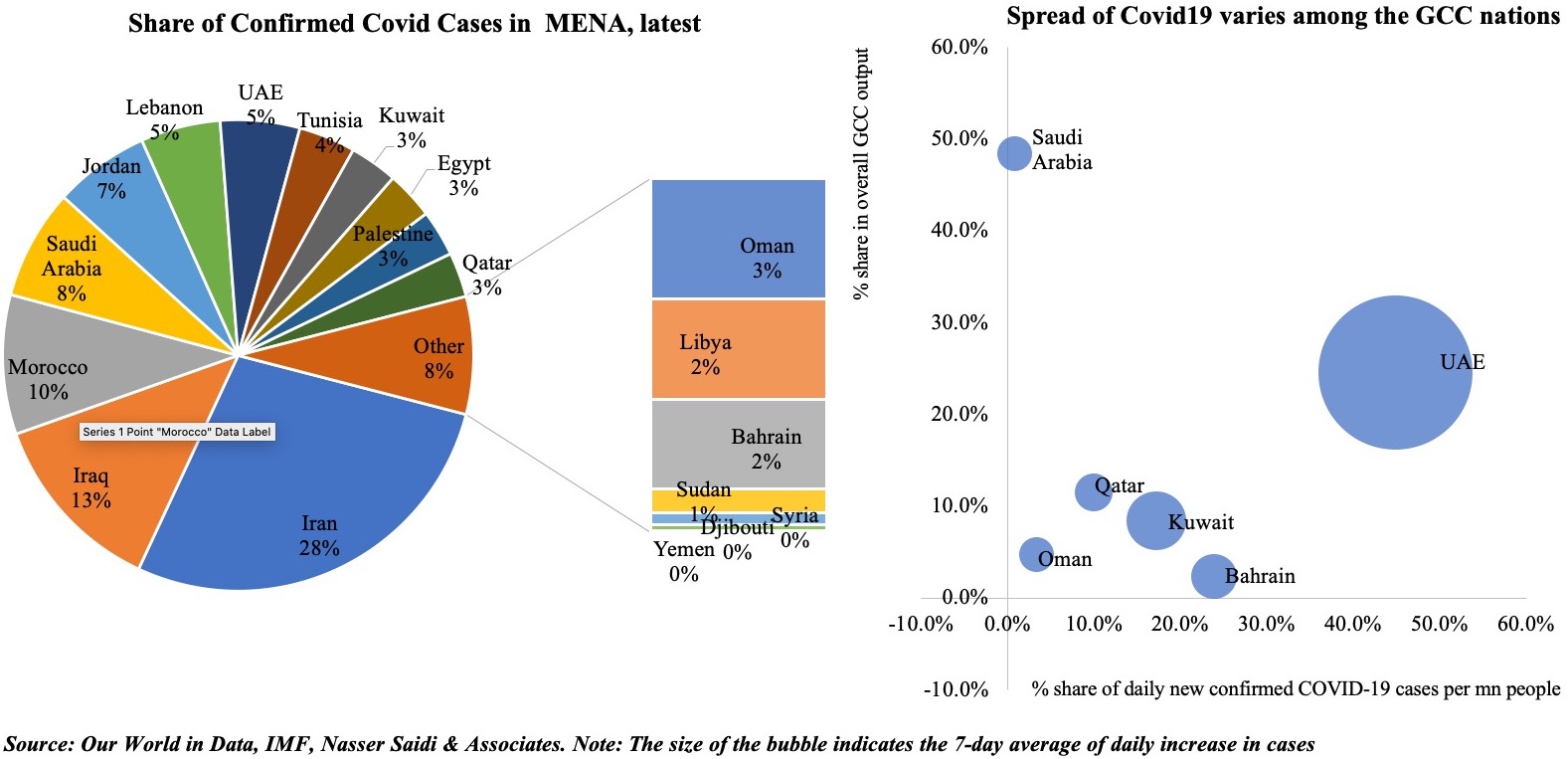

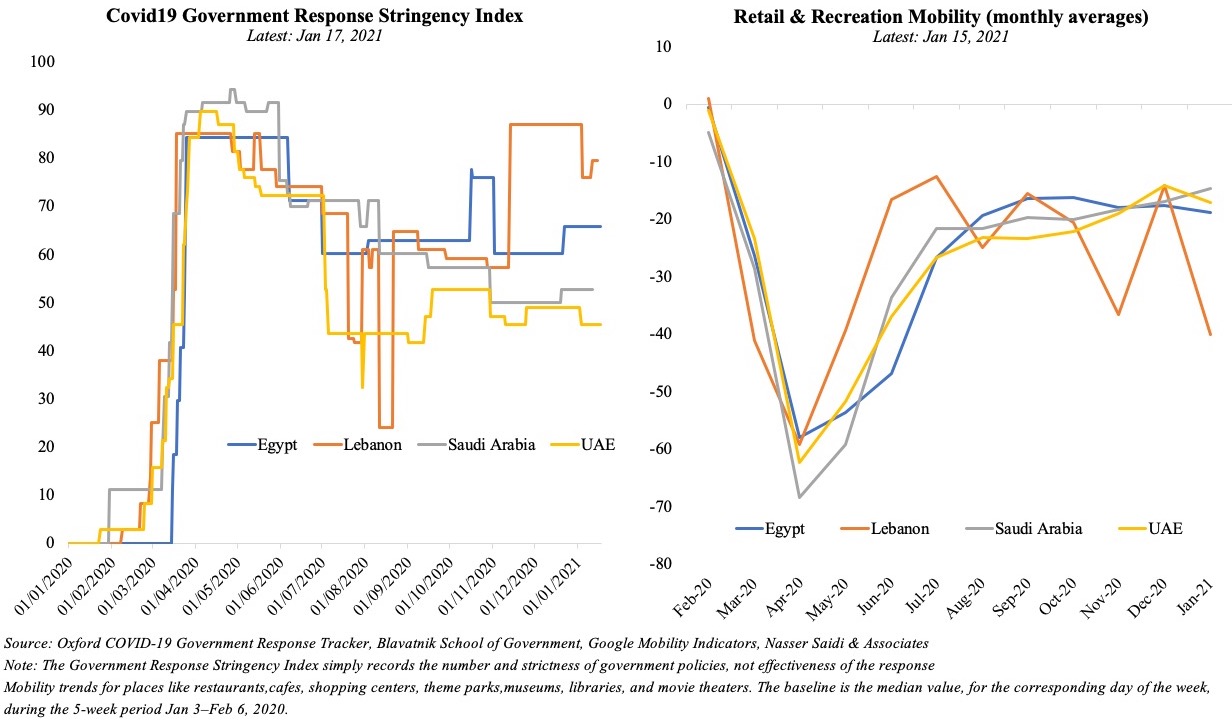

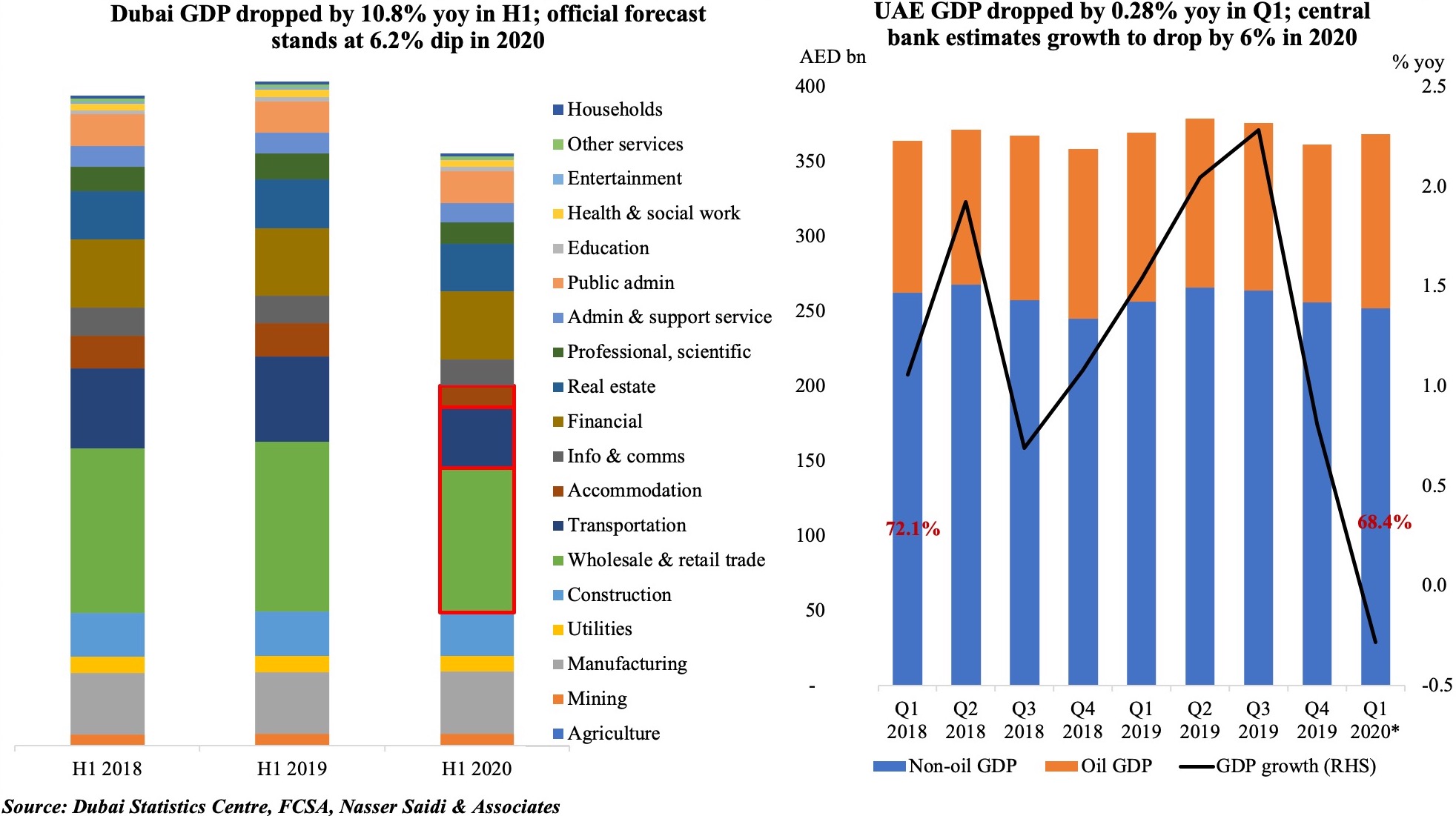

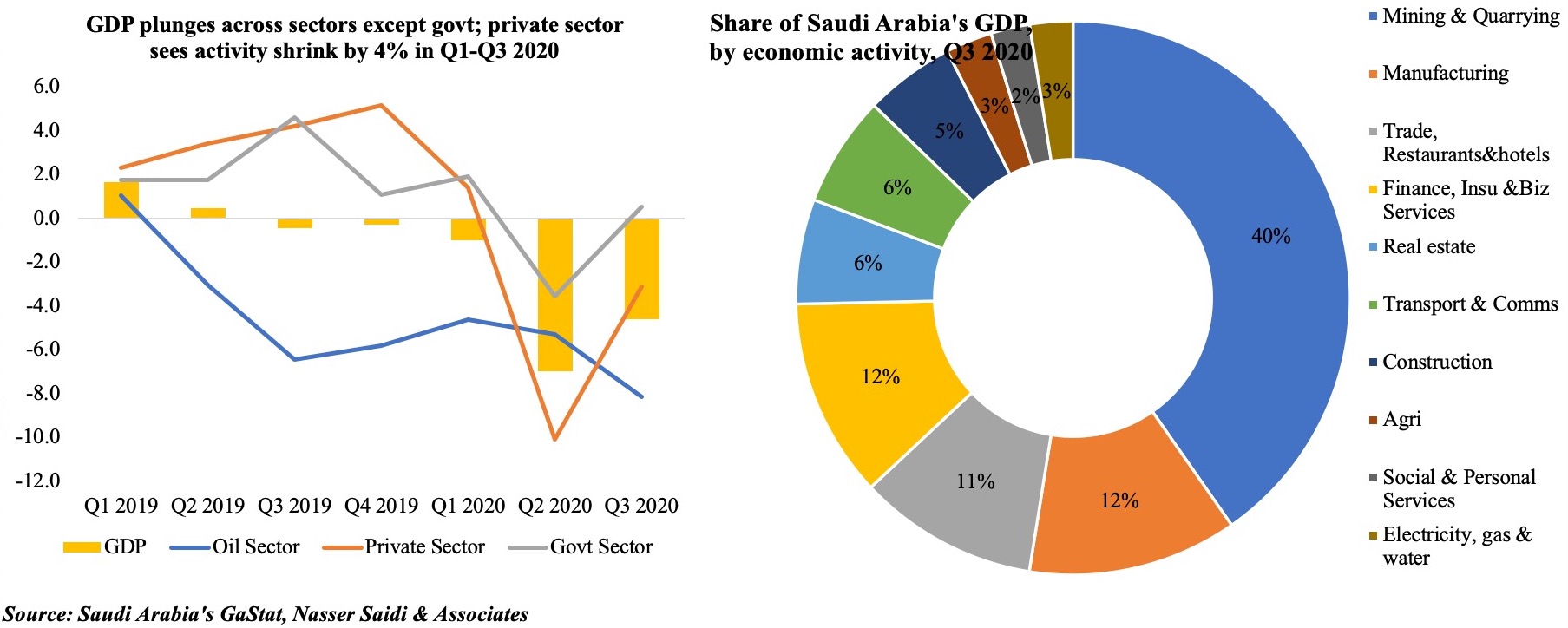

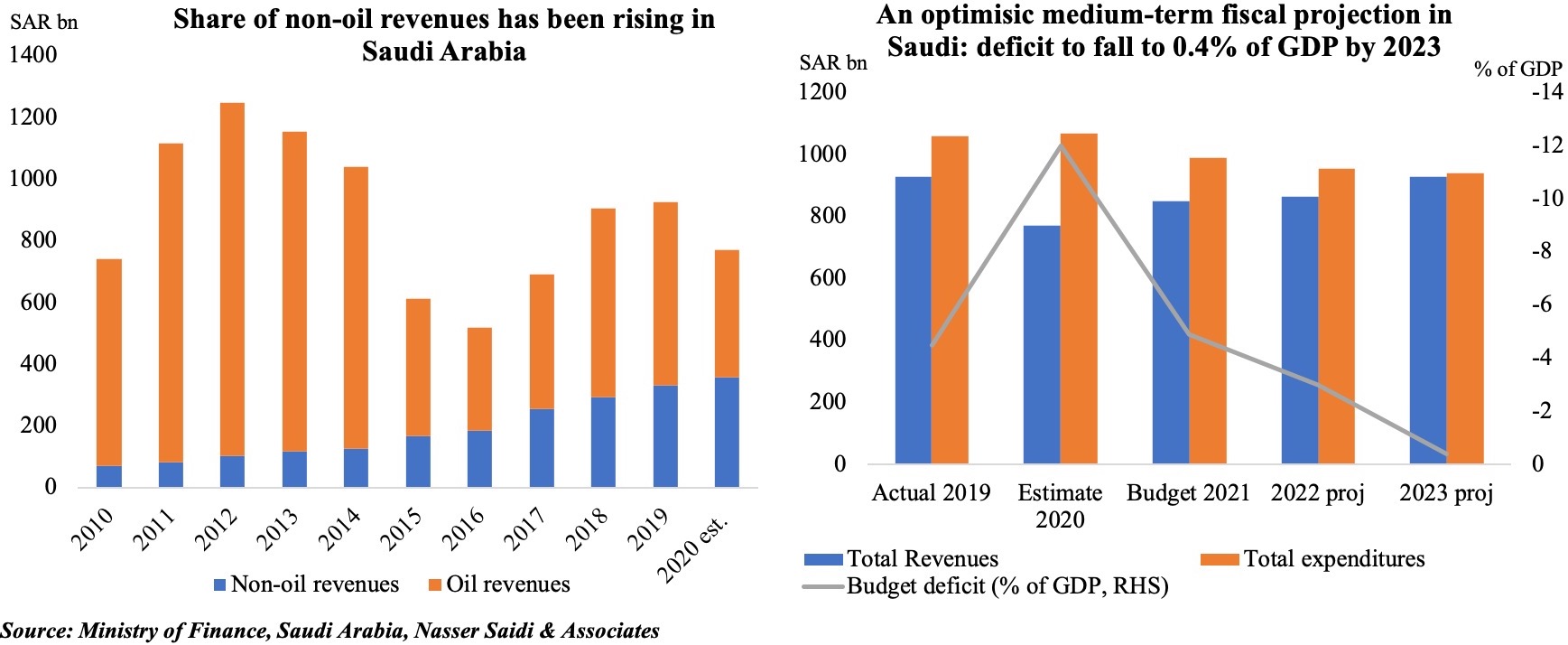

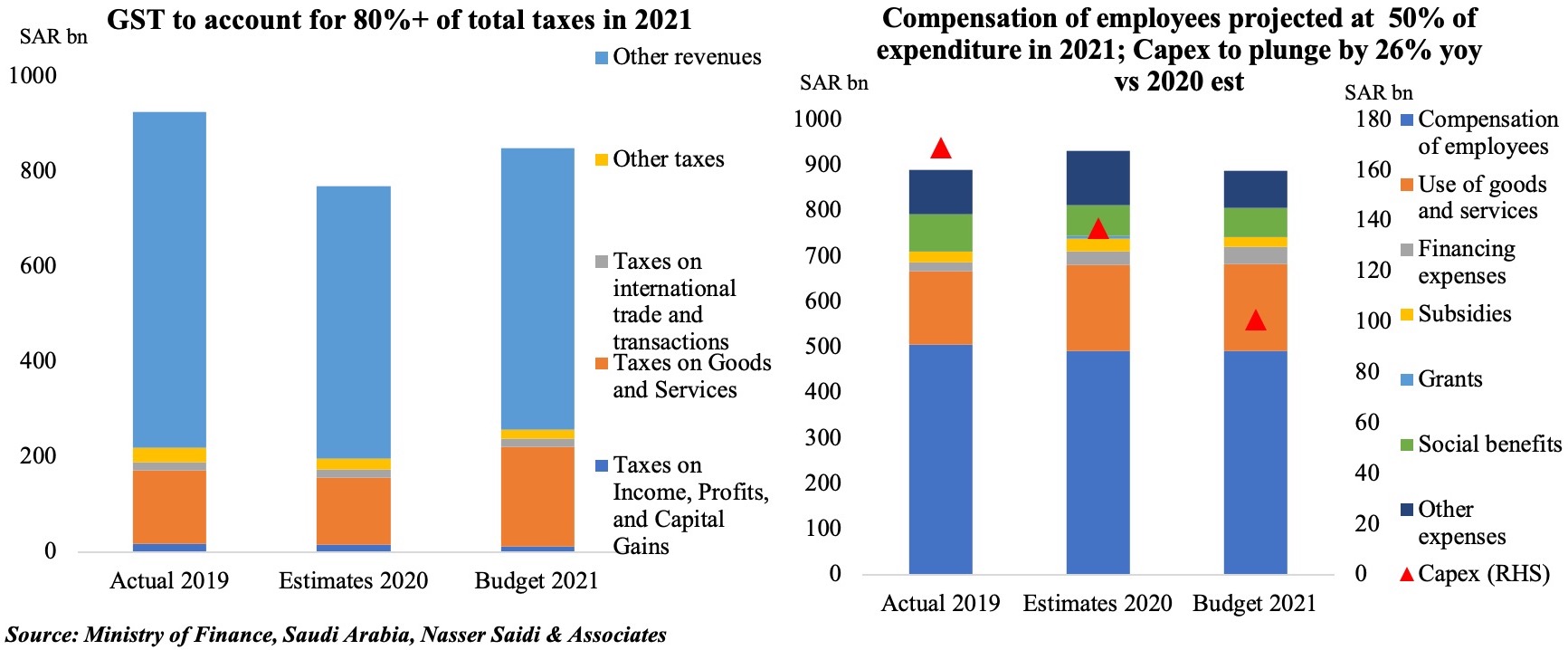

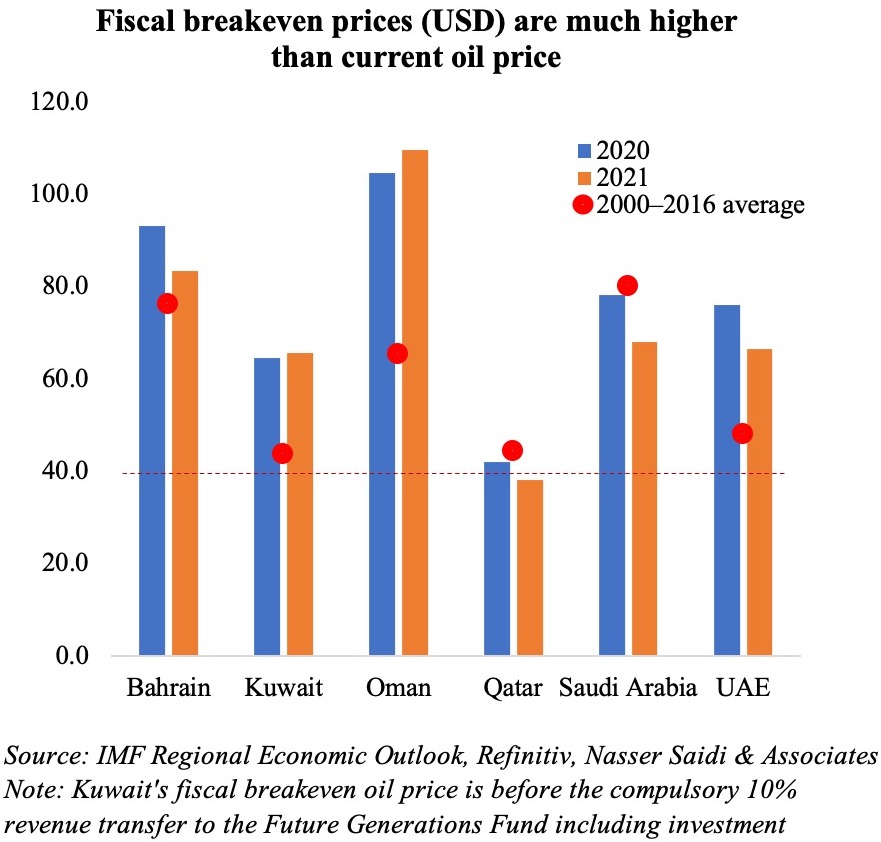

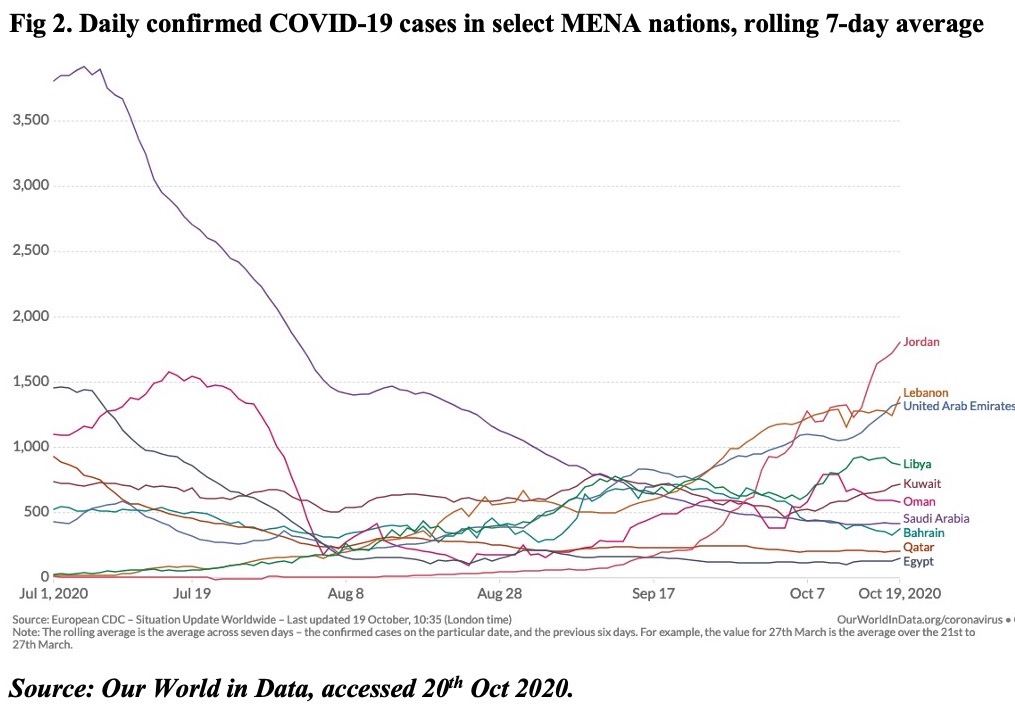

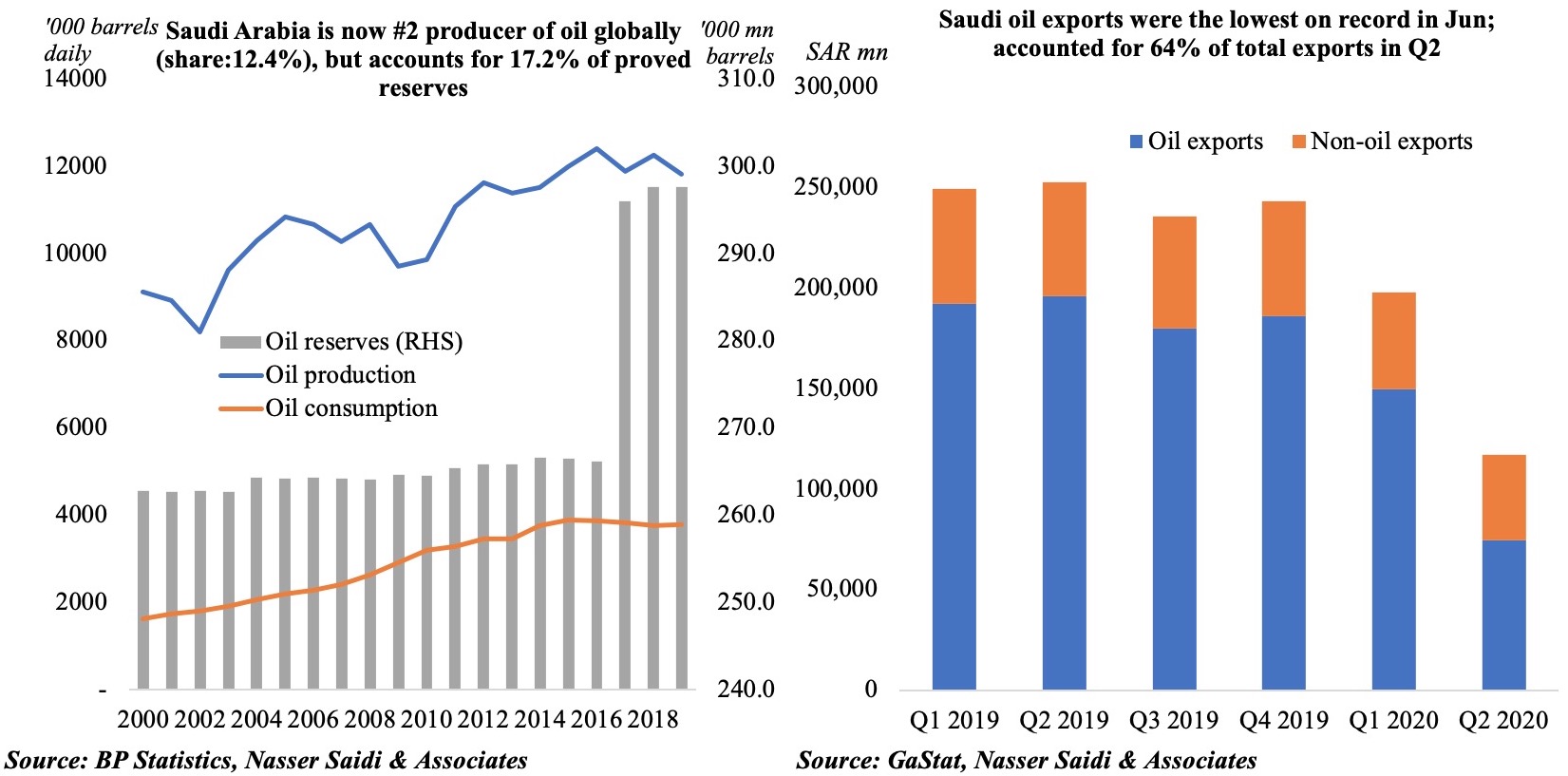

However, policy measures introduced to support the economy during the pandemic is creating immense fiscal strain. Fiscal deficits widened to 10.1% of GDP in 2020 in the MENA region from 3.8% in 2019. It was severe in the GCC as well: fiscal deficit widened to 7.6% of GDP last year (2019: -1.6%), as the impact was from both lower oil and non-oil revenues. The fiscal breakeven price this year ranges from a high USD 88.2 in Bahrain to a low USD 43.1 in Qatar. While, it is expected to decline across the board next year, it still remains higher than the current oil price levels for most nations. Given new rounds of restrictions and with oil demand not yet at pre-pandemic levels, the OPEC+’s recent decision to roll back production cuts are likely to depress oil prices. As real oil prices trend downward, fiscal sustainability becomes increasingly vulnerable.

However, policy measures introduced to support the economy during the pandemic is creating immense fiscal strain. Fiscal deficits widened to 10.1% of GDP in 2020 in the MENA region from 3.8% in 2019. It was severe in the GCC as well: fiscal deficit widened to 7.6% of GDP last year (2019: -1.6%), as the impact was from both lower oil and non-oil revenues. The fiscal breakeven price this year ranges from a high USD 88.2 in Bahrain to a low USD 43.1 in Qatar. While, it is expected to decline across the board next year, it still remains higher than the current oil price levels for most nations. Given new rounds of restrictions and with oil demand not yet at pre-pandemic levels, the OPEC+’s recent decision to roll back production cuts are likely to depress oil prices. As real oil prices trend downward, fiscal sustainability becomes increasingly vulnerable.

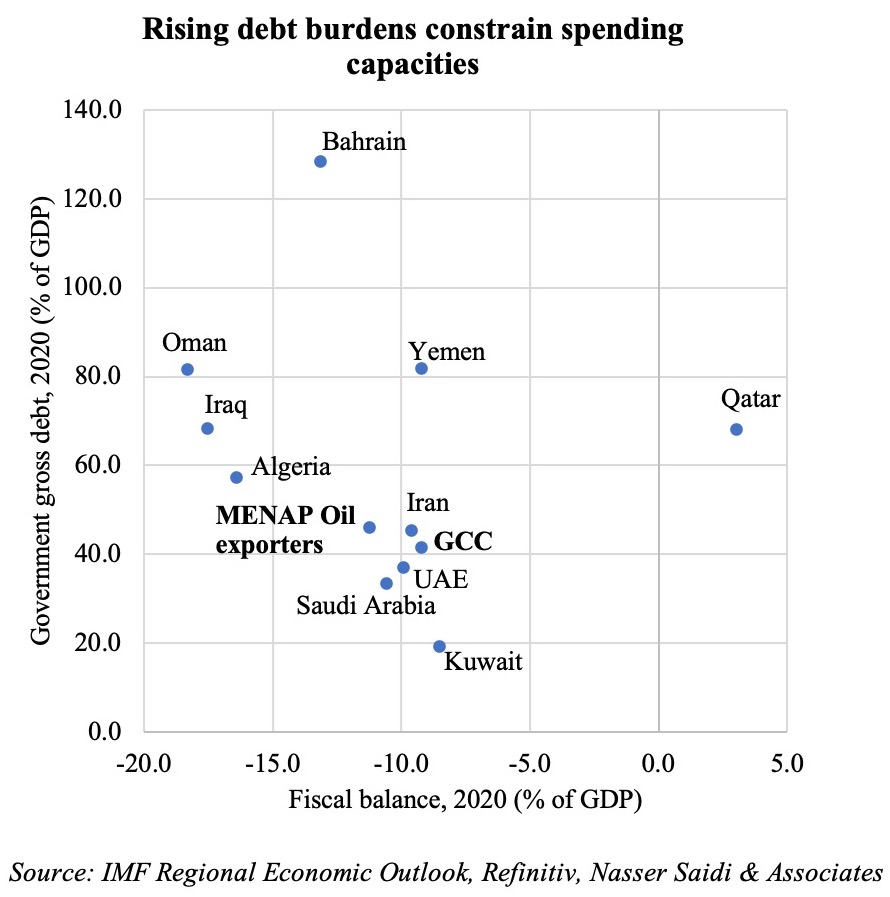

Higher deficits and negative economic growth resulted in governments resorting to multiple financing options: borrowing from commercial banks, tapping international and regional markets (bond issuances, commercial loans) as well as drawing down from international reserves at the central banks/ sovereign wealth funds. Government debt levels increased to 56.4% and 41% in the MENA and GCC regions last year. Though it is forecast to fall slightly this year, it still remains higher than the 2000-17 average of 36.2% and 24.6% respectively. The IMF estimates financing needs in the MENA to touch USD 919bn for this year and next. Public-financing requirements were likely to stay above 15% of GDP in most parts of the region through end-2022.

Higher deficits and negative economic growth resulted in governments resorting to multiple financing options: borrowing from commercial banks, tapping international and regional markets (bond issuances, commercial loans) as well as drawing down from international reserves at the central banks/ sovereign wealth funds. Government debt levels increased to 56.4% and 41% in the MENA and GCC regions last year. Though it is forecast to fall slightly this year, it still remains higher than the 2000-17 average of 36.2% and 24.6% respectively. The IMF estimates financing needs in the MENA to touch USD 919bn for this year and next. Public-financing requirements were likely to stay above 15% of GDP in most parts of the region through end-2022.

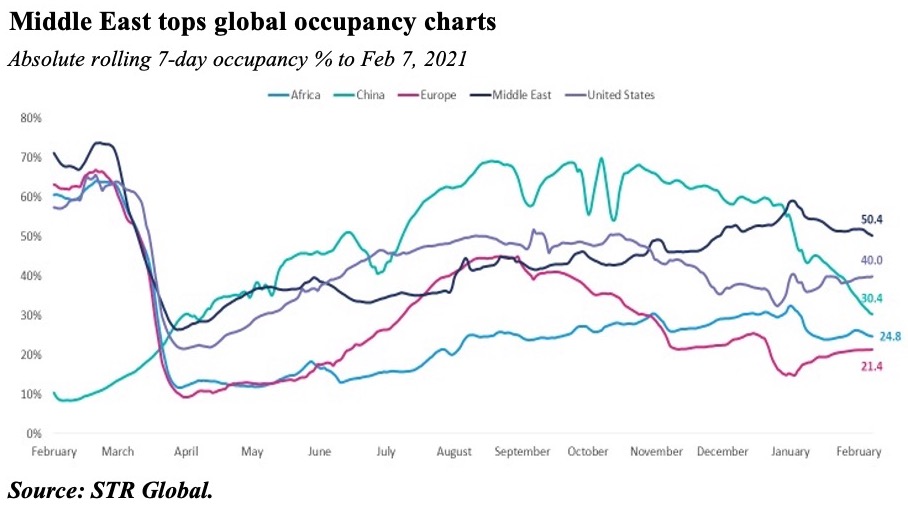

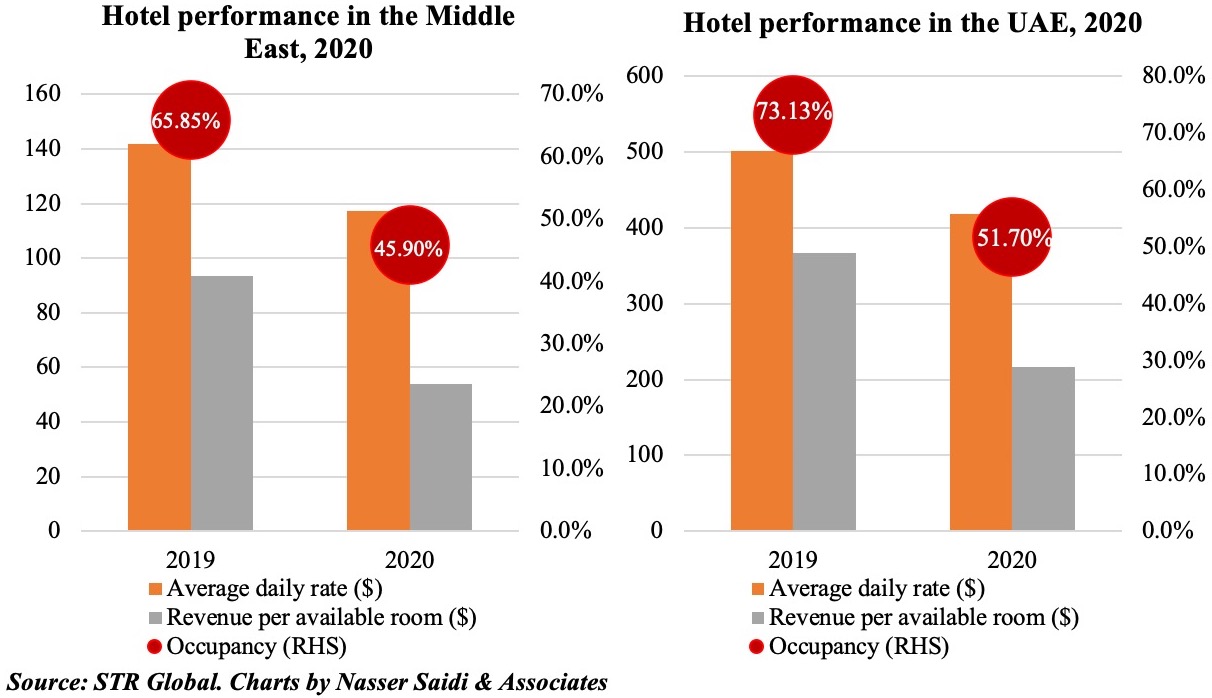

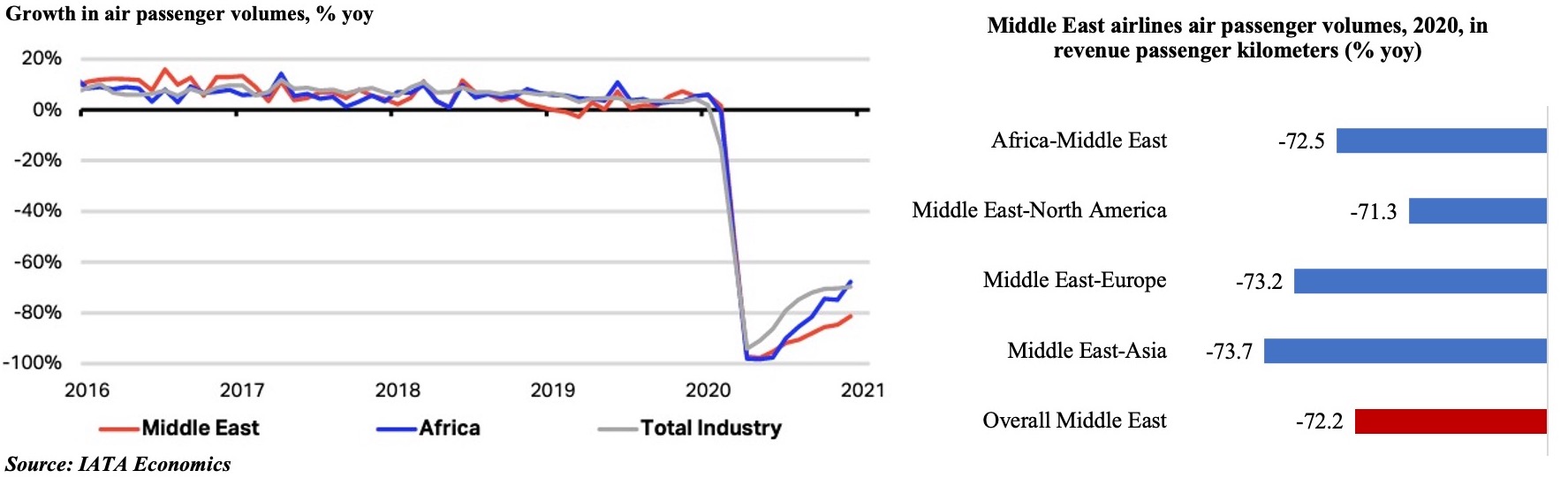

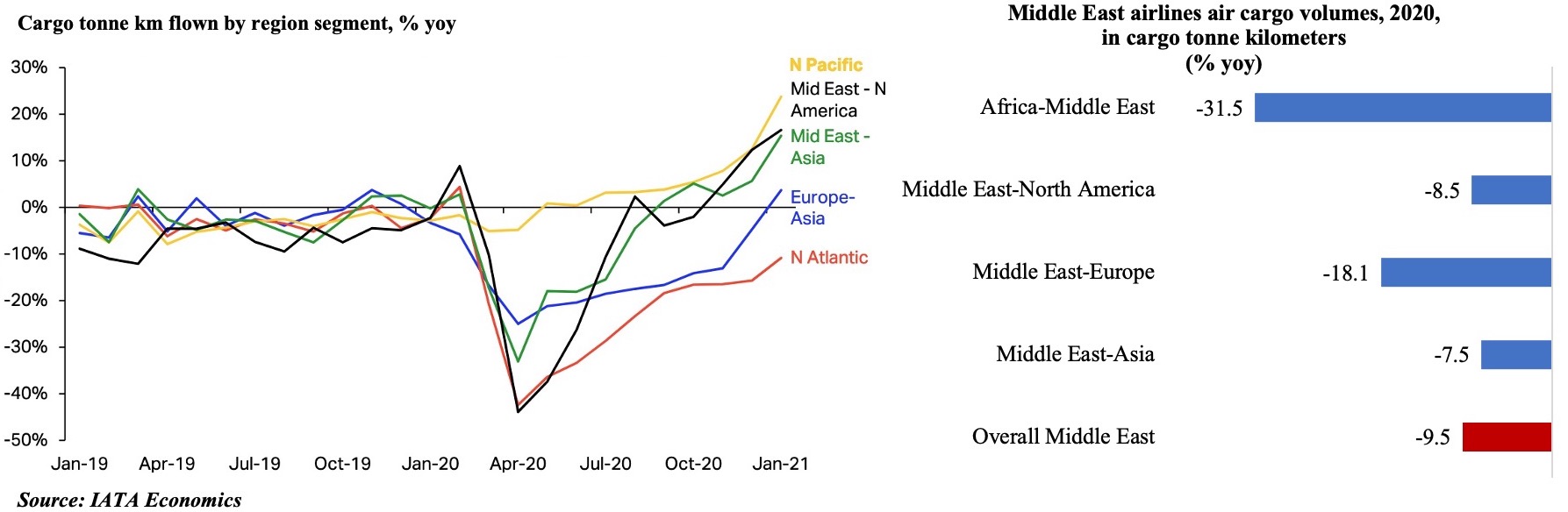

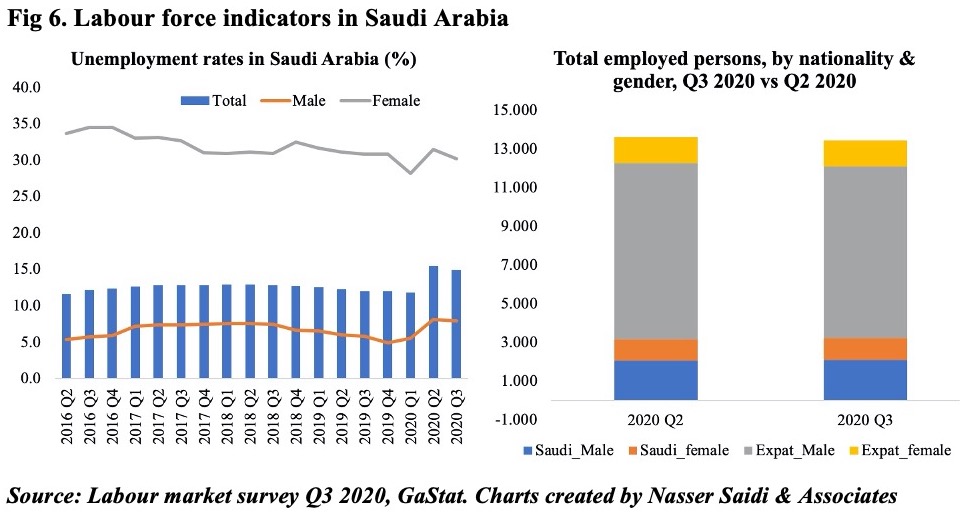

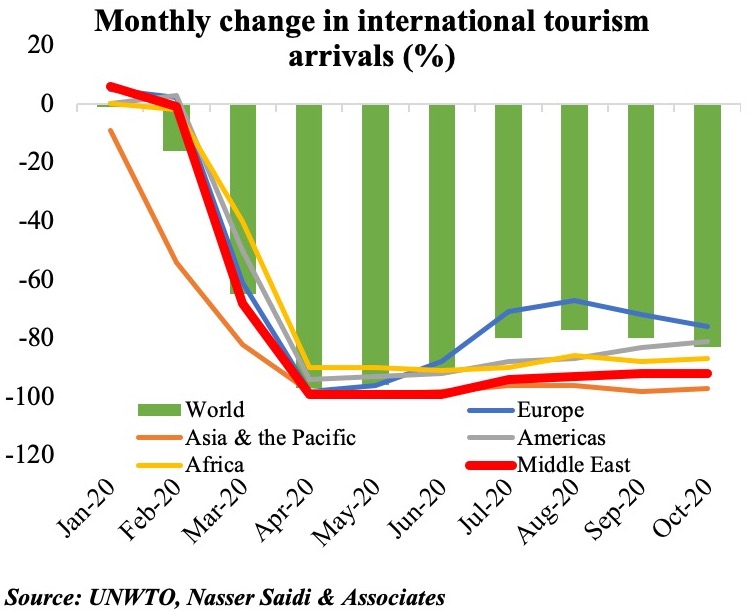

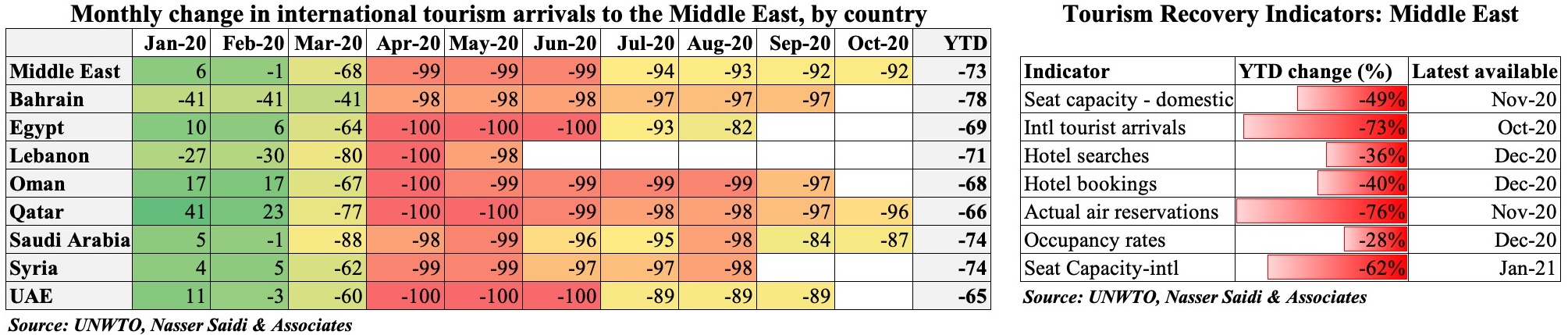

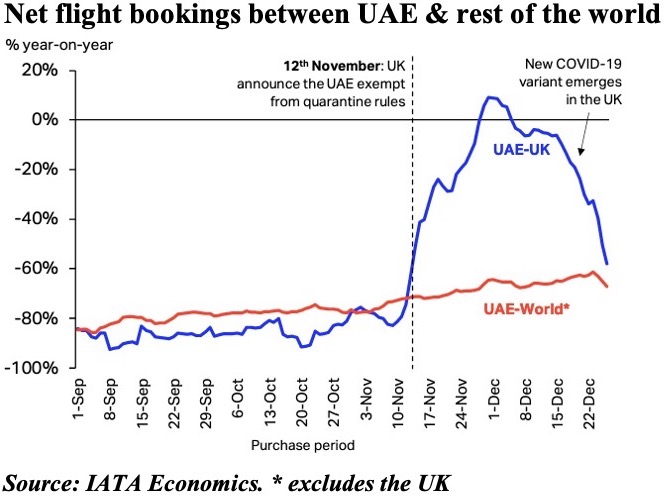

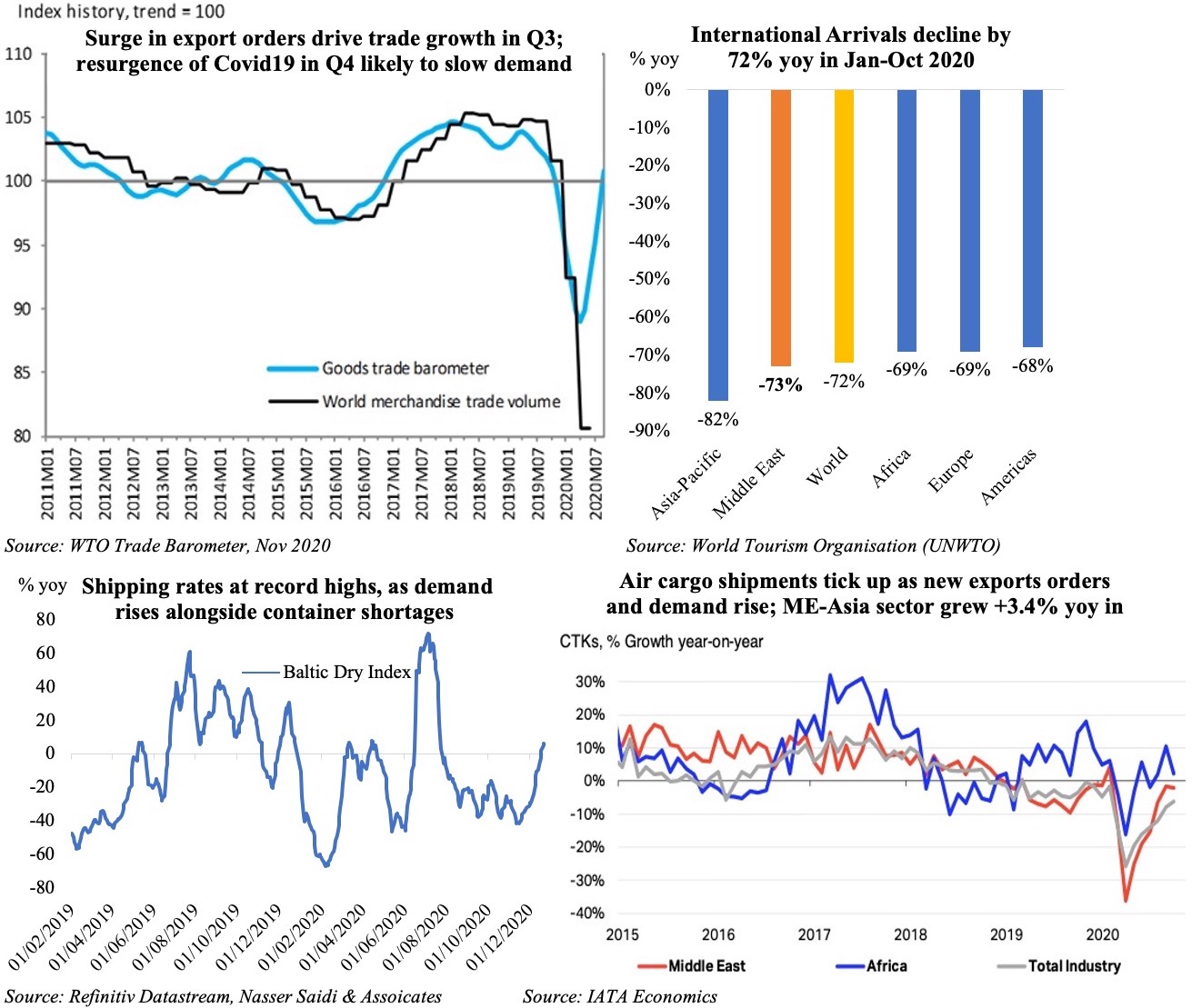

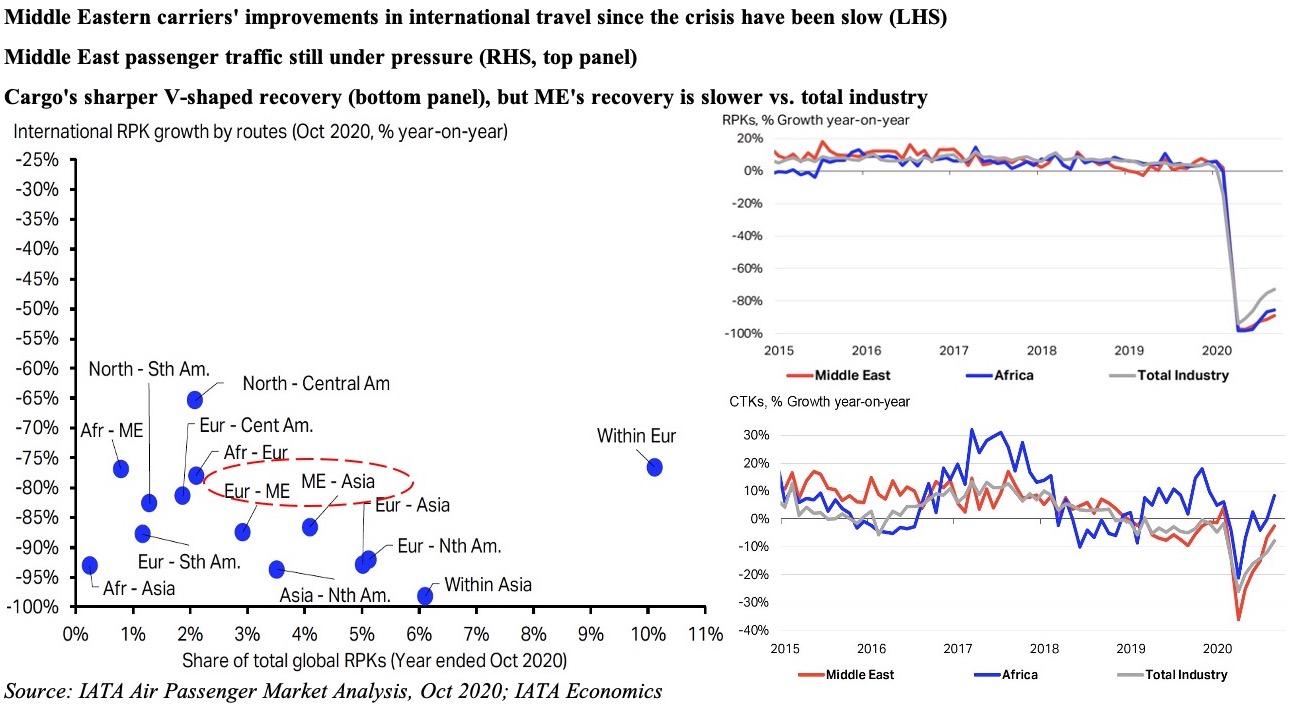

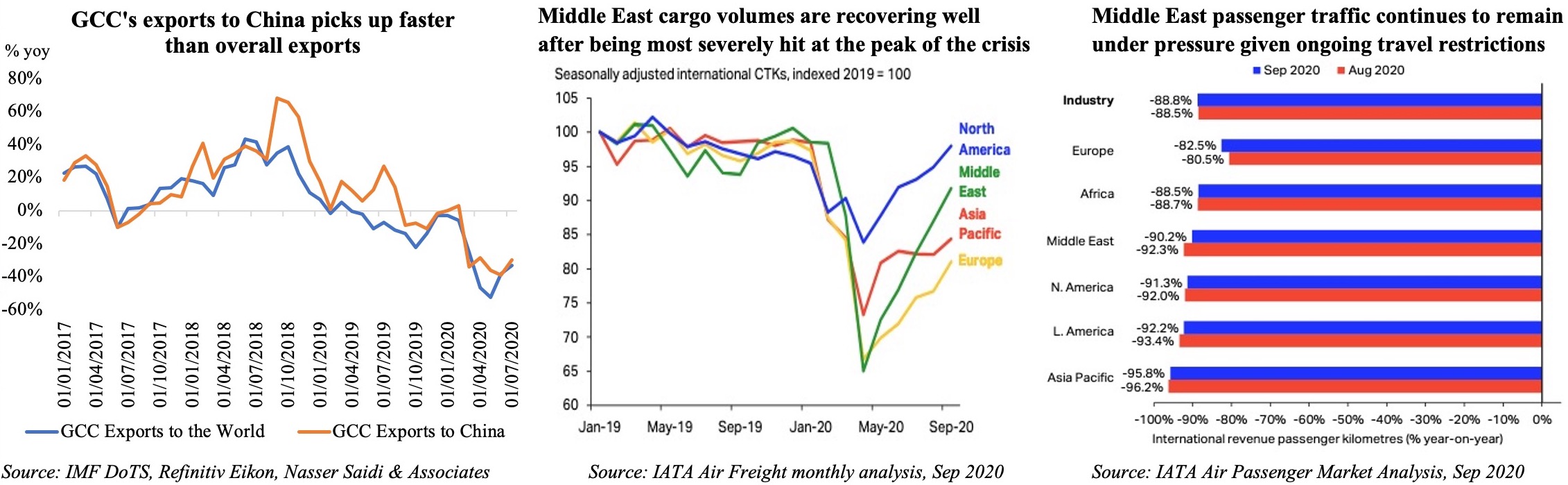

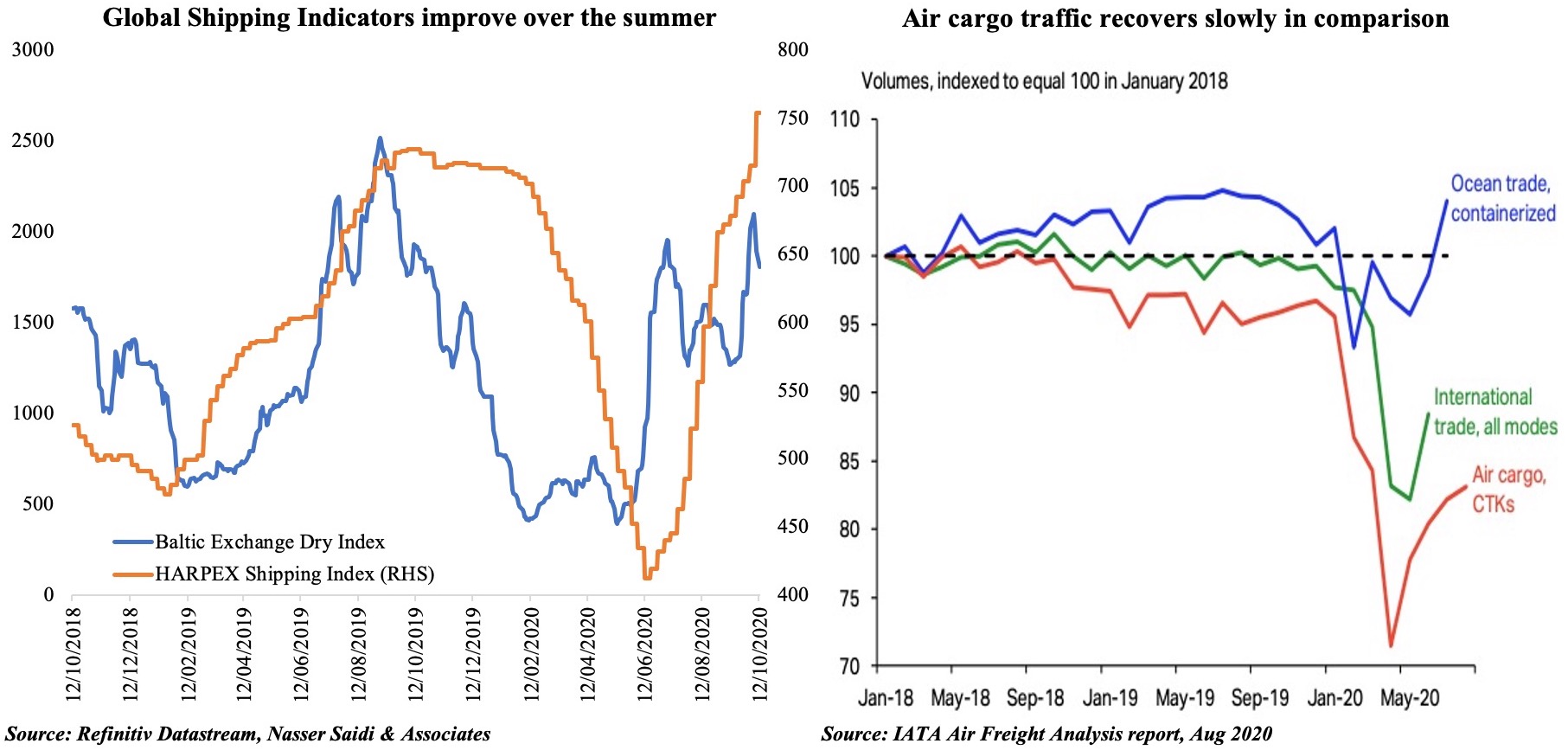

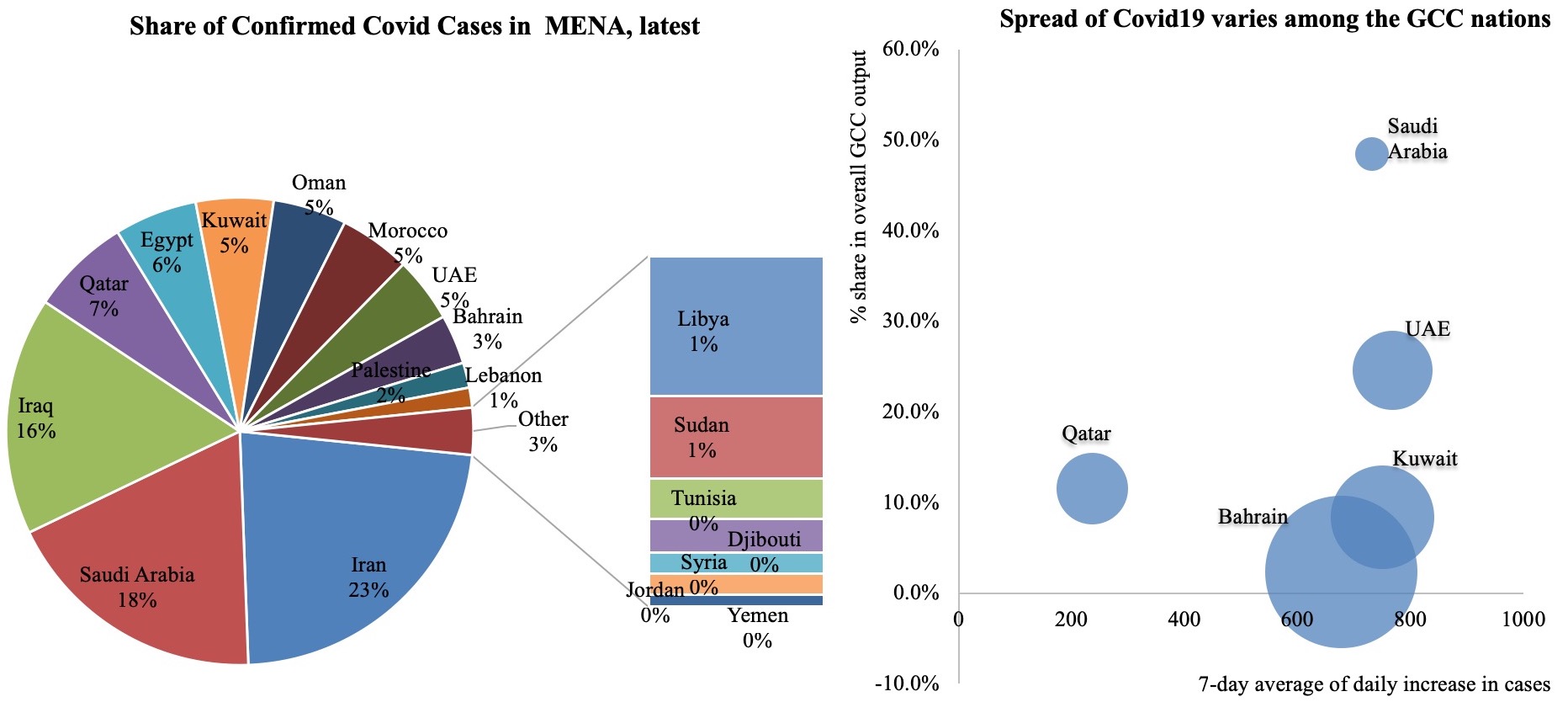

The UNWTO reported a 72% drop in international tourist arrivals during the Jan-Oct period, with the Middle East region continuing to lag its global counterparts in tourism arrivals (-73% year-to-date). International tourism as a share of total tourism is significantly high in Bahrain (97%) and UAE (83%), making these nations more vulnerable than say, Saudi Arabia, with its share at 26%. With air travel restrictions still in place in many nations, and hotels either closed or open at lower capacity, the road to recovery will be long.

The UNWTO reported a 72% drop in international tourist arrivals during the Jan-Oct period, with the Middle East region continuing to lag its global counterparts in tourism arrivals (-73% year-to-date). International tourism as a share of total tourism is significantly high in Bahrain (97%) and UAE (83%), making these nations more vulnerable than say, Saudi Arabia, with its share at 26%. With air travel restrictions still in place in many nations, and hotels either closed or open at lower capacity, the road to recovery will be long.

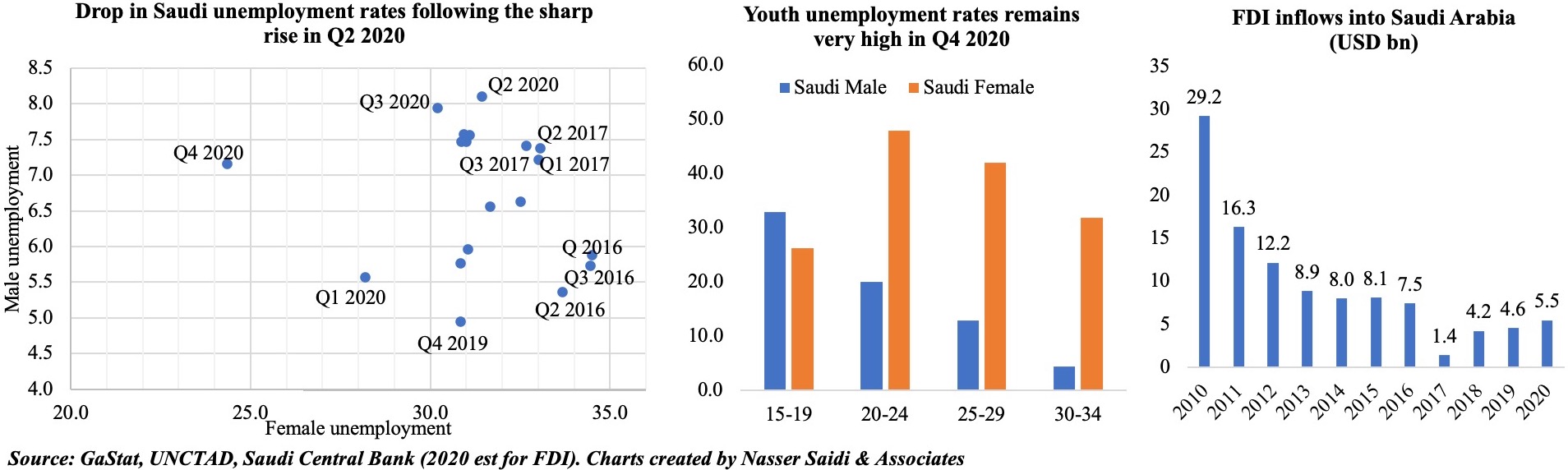

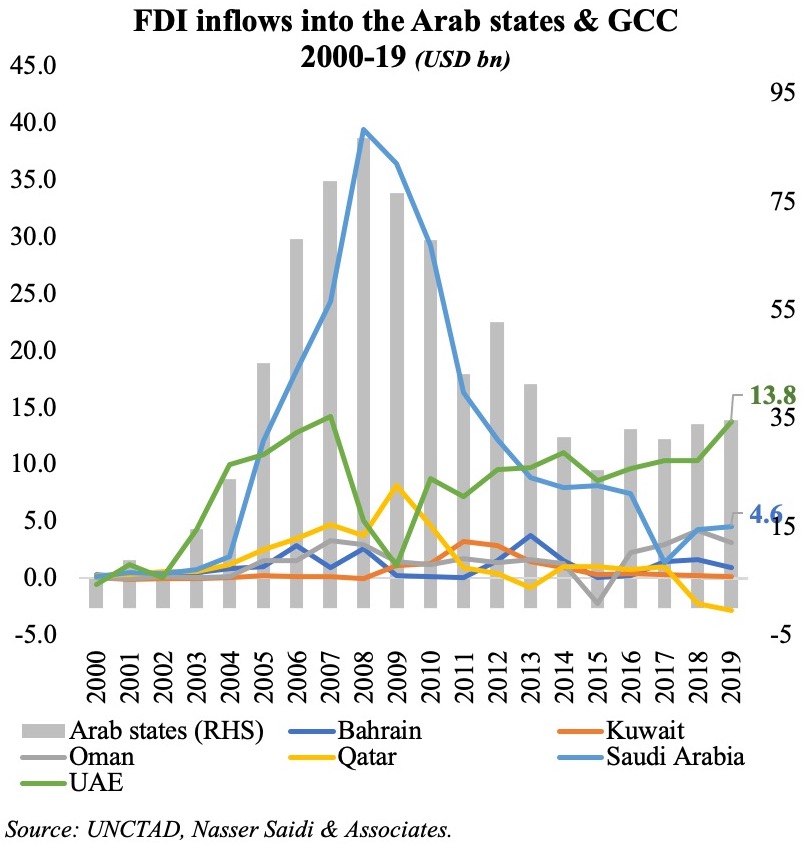

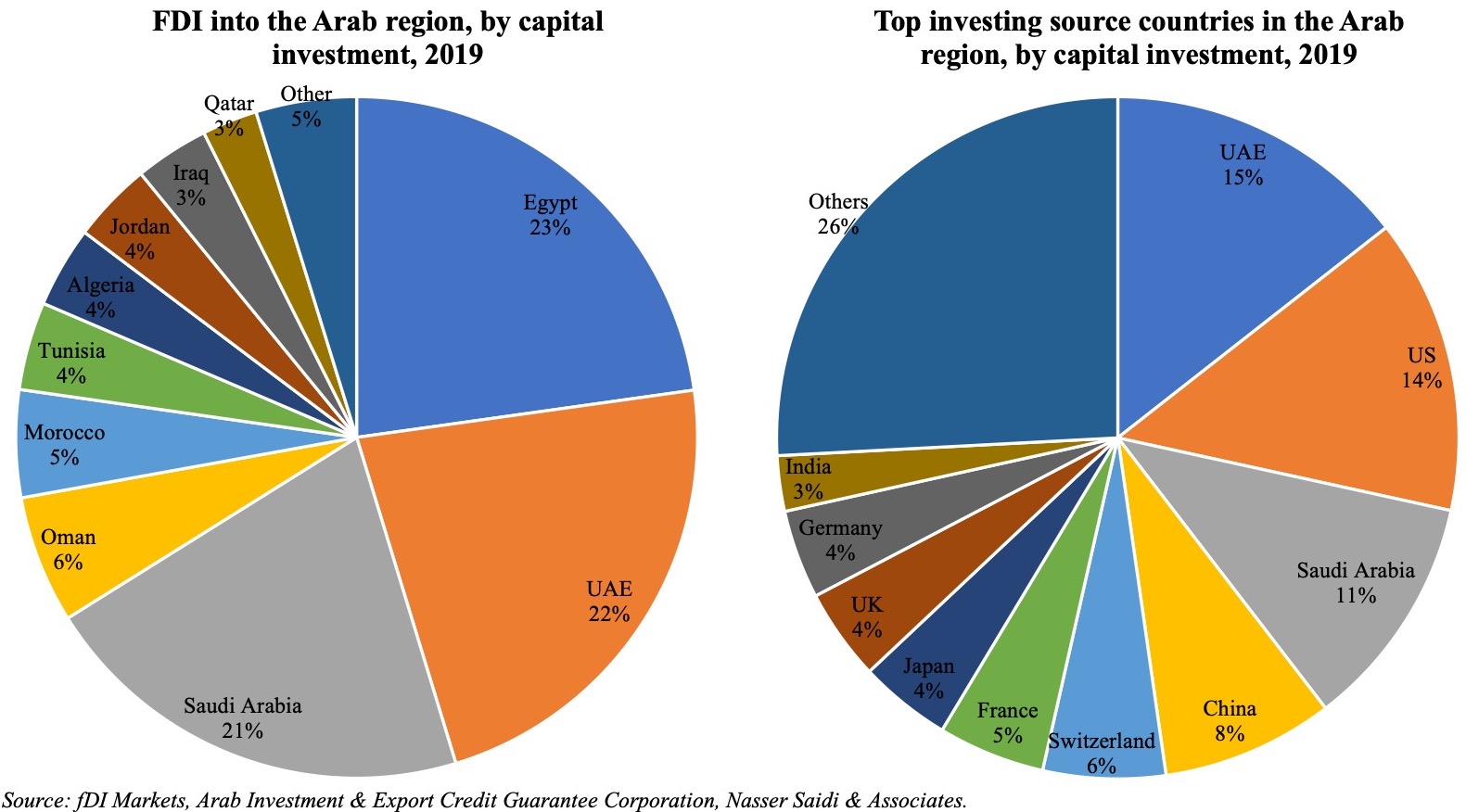

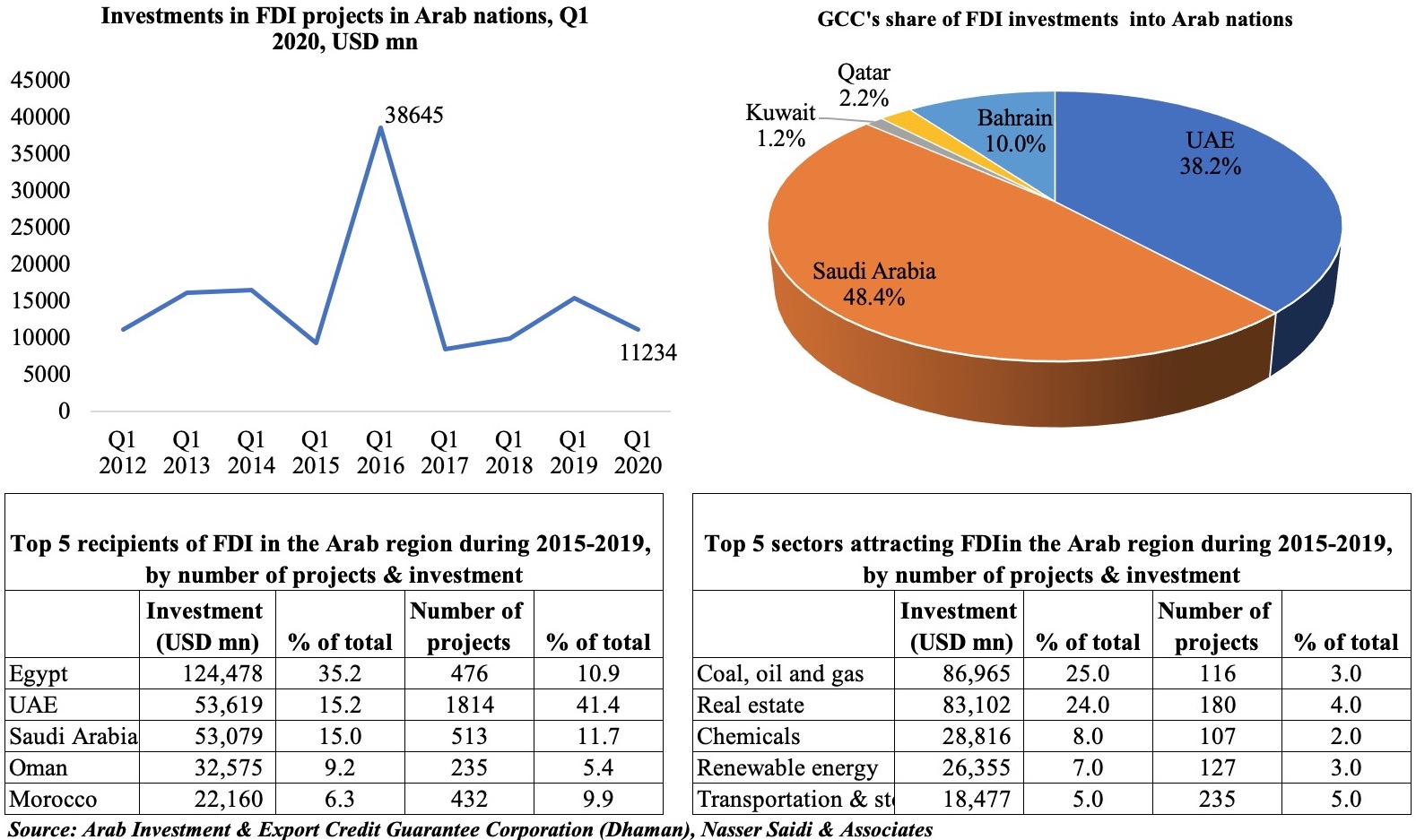

We focus on FDI in this Weekly Insight piece. FDI inflows are essential to the UAE’s diversification efforts, as it would not only create jobs, raise productivity and growth, but could also lead to transfer of technology/ technical know-how and promote competition in the market. According to the IMF, closing FDI gaps in the GCC could raise real non-oil GDP per capita growth by as much as 1 percentage point.

We focus on FDI in this Weekly Insight piece. FDI inflows are essential to the UAE’s diversification efforts, as it would not only create jobs, raise productivity and growth, but could also lead to transfer of technology/ technical know-how and promote competition in the market. According to the IMF, closing FDI gaps in the GCC could raise real non-oil GDP per capita growth by as much as 1 percentage point.

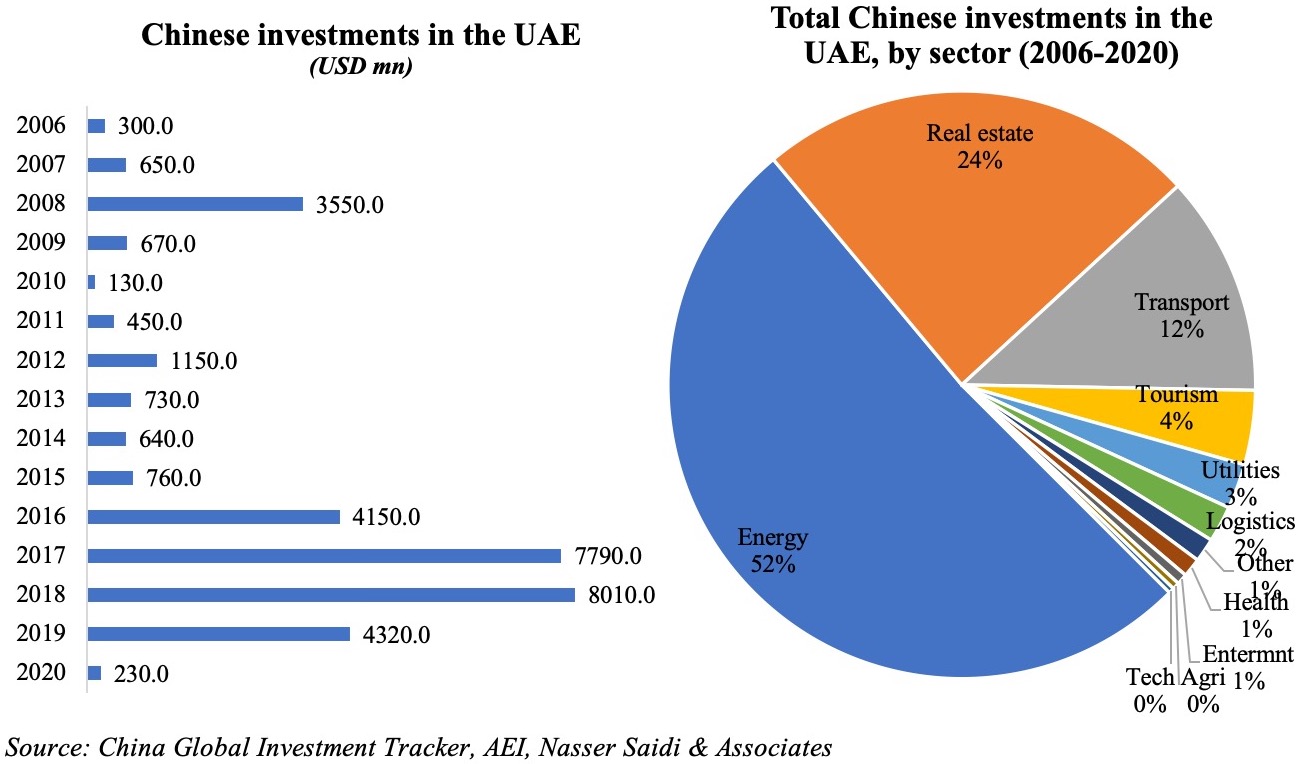

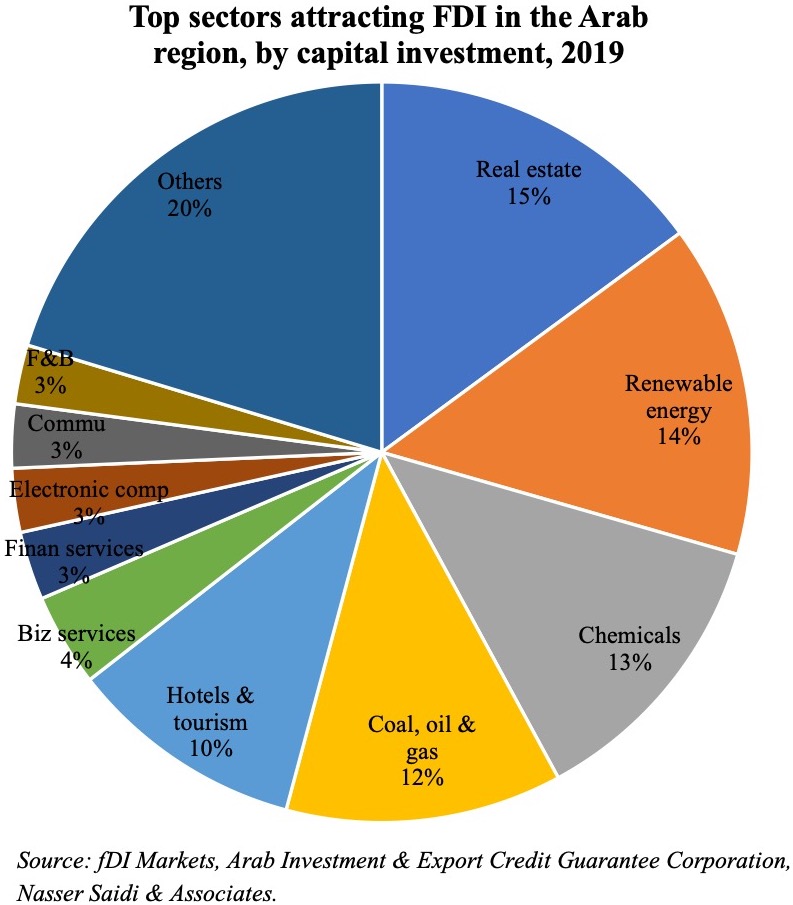

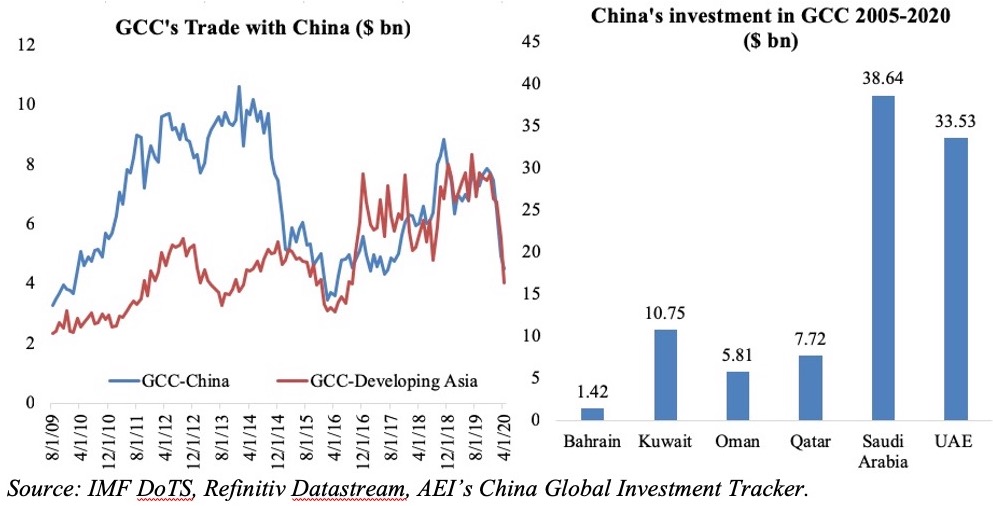

hinese projects tracked during Jan 2003-Mar 2020 (with the number of projects in double-digits in 2018 and 2019). According to AEI’s China Global Investment Tracker, the value of Chinese investments touched a high of USD 8bn in 2018, thanks to a handful of large projects (including with ACWA Power and Abu Dhabi Oil). Sector-wise, investments were concentrated in energy (both oil and gas as well as renewables), real estate and transport – together accounting for 87.8% of total investments during 2016-2020. This is largely in line with FDI inflows into the Arab region as well, with the top 5 sectors (real estate, renewables, chemicals, oil & gas and travel & tourism) accounting for close to two-thirds of total inflows in 2019.

hinese projects tracked during Jan 2003-Mar 2020 (with the number of projects in double-digits in 2018 and 2019). According to AEI’s China Global Investment Tracker, the value of Chinese investments touched a high of USD 8bn in 2018, thanks to a handful of large projects (including with ACWA Power and Abu Dhabi Oil). Sector-wise, investments were concentrated in energy (both oil and gas as well as renewables), real estate and transport – together accounting for 87.8% of total investments during 2016-2020. This is largely in line with FDI inflows into the Arab region as well, with the top 5 sectors (real estate, renewables, chemicals, oil & gas and travel & tourism) accounting for close to two-thirds of total inflows in 2019.

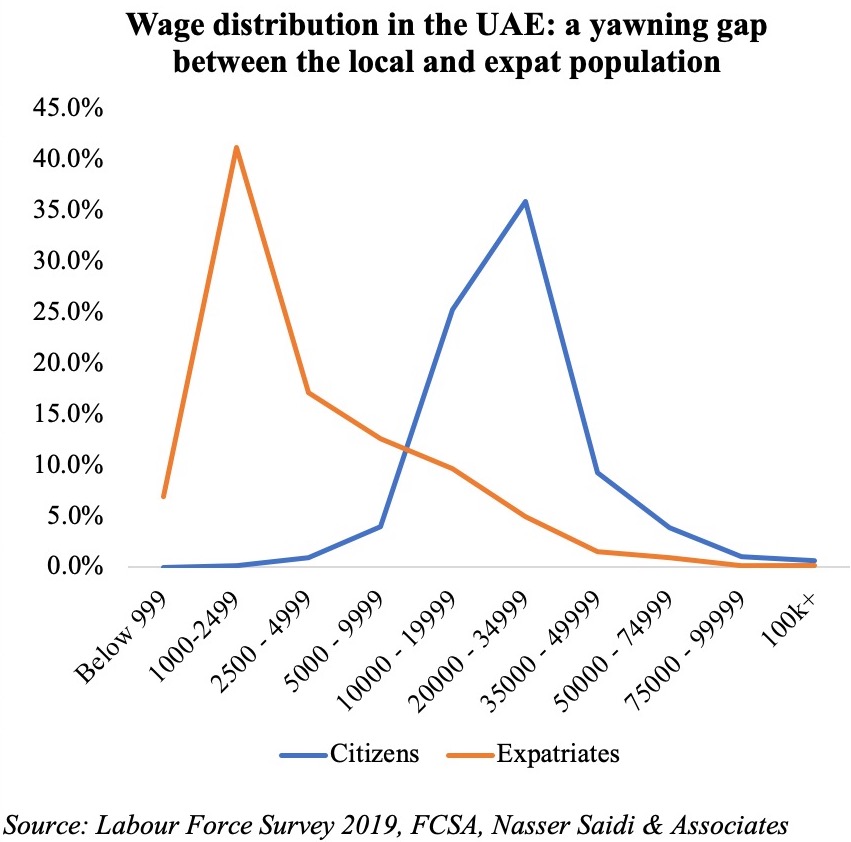

The Survey also confirms the disparity in wages between local and expat population: more than one-third of Emirati respondents disclosed receiving monthly wages between AED 20-35k (versus just 5% of expats in the same income bracket). This brings to the forefront two issues:

The Survey also confirms the disparity in wages between local and expat population: more than one-third of Emirati respondents disclosed receiving monthly wages between AED 20-35k (versus just 5% of expats in the same income bracket). This brings to the forefront two issues:

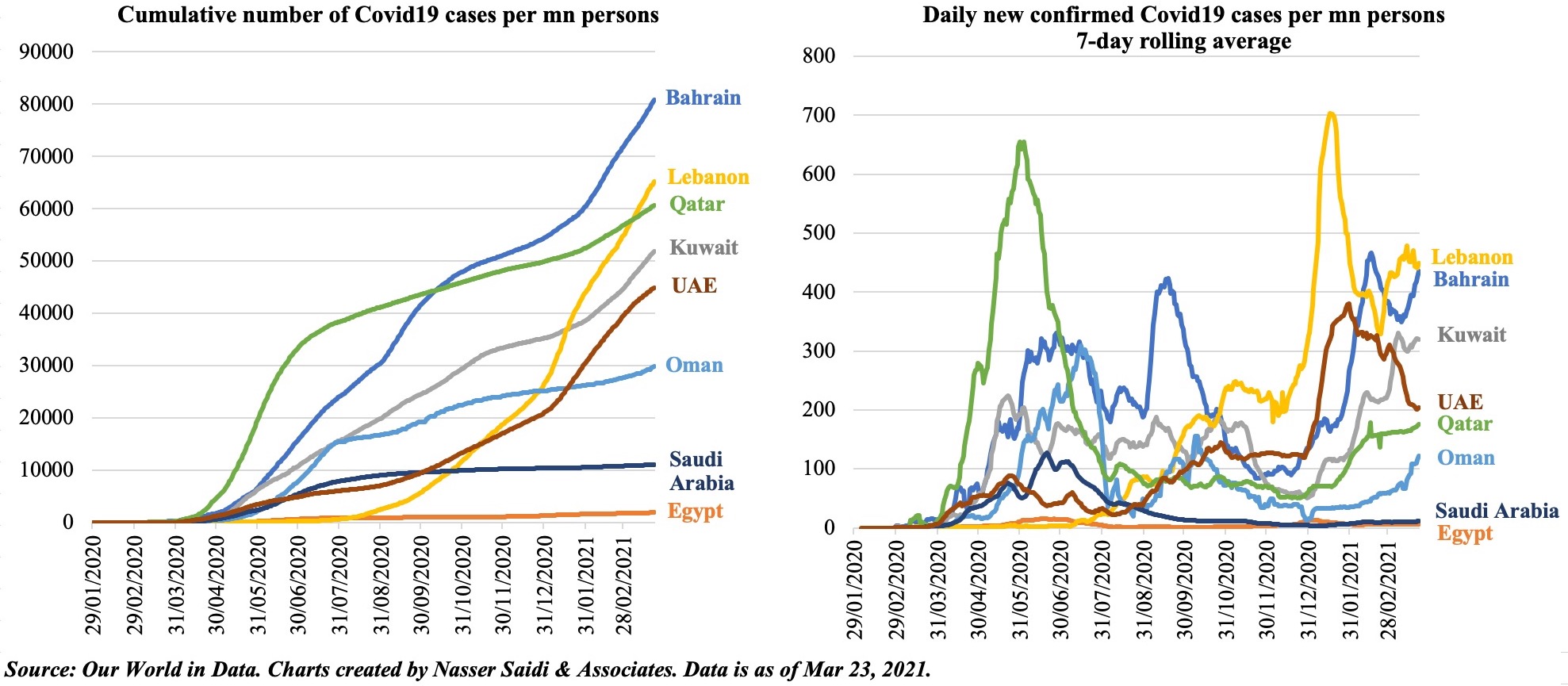

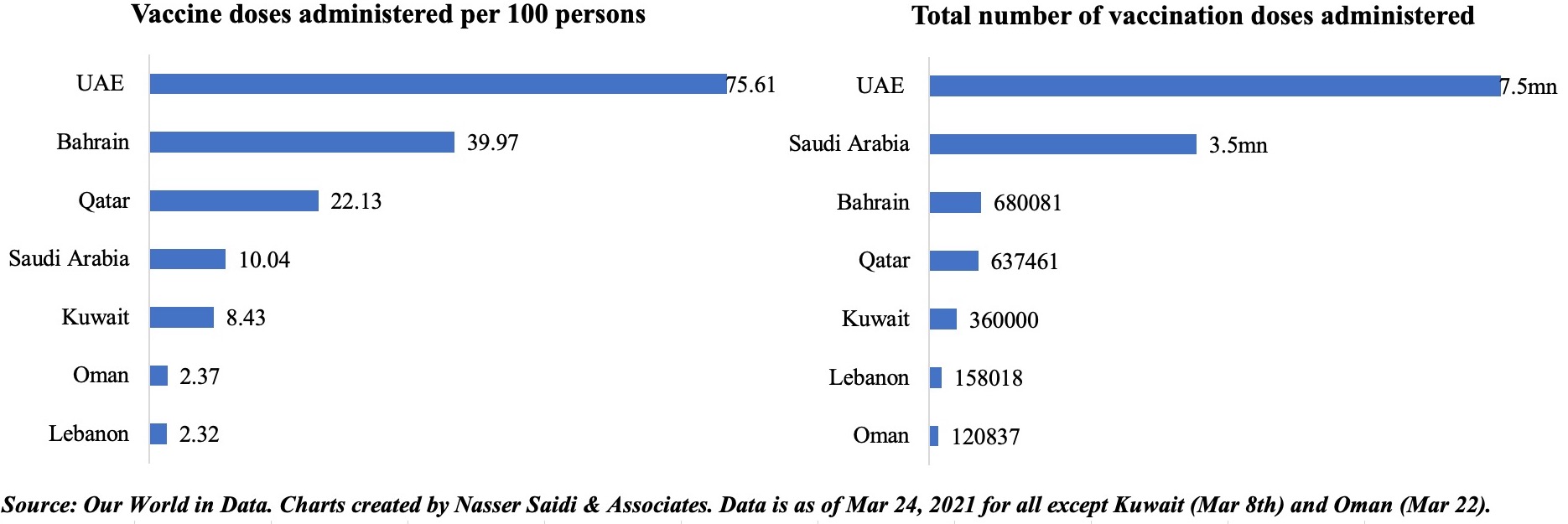

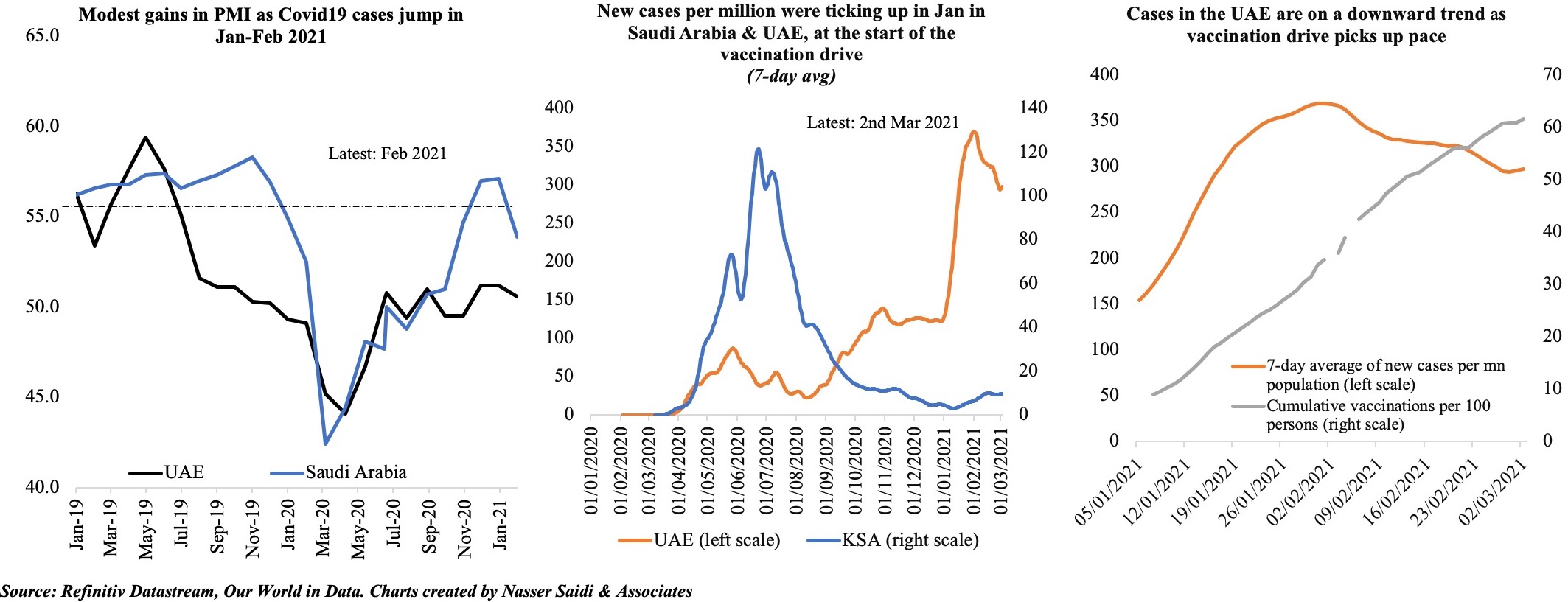

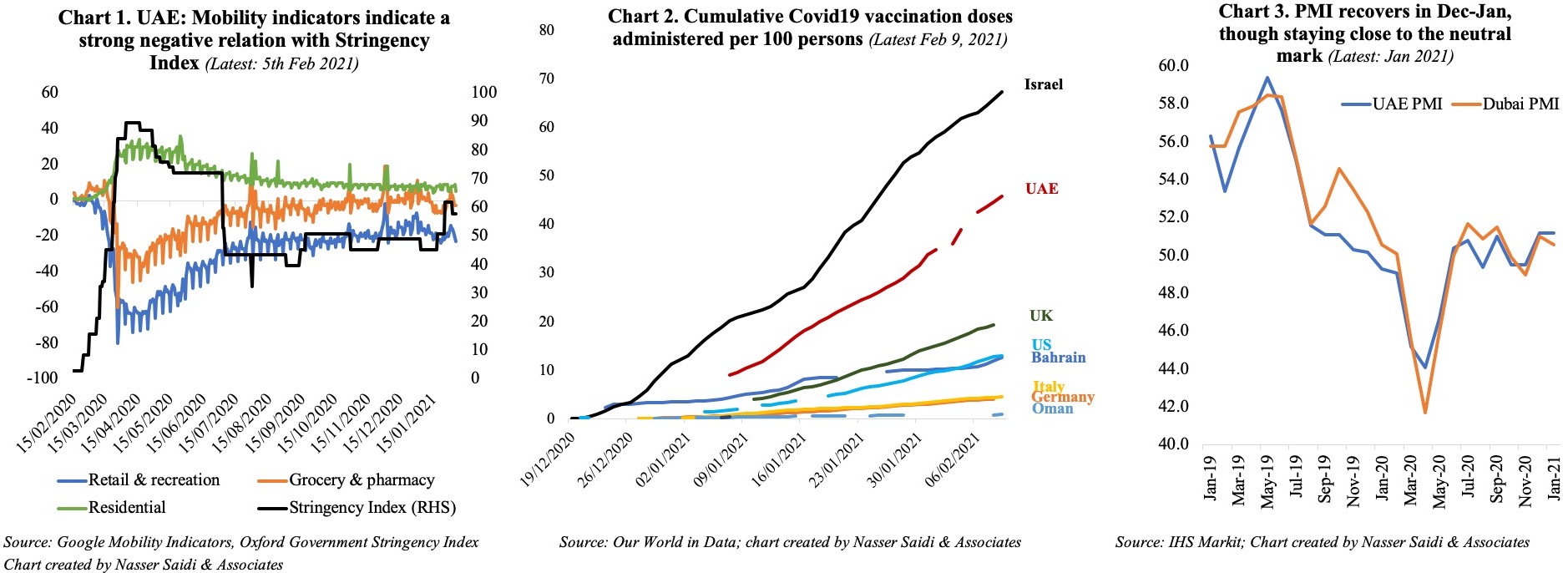

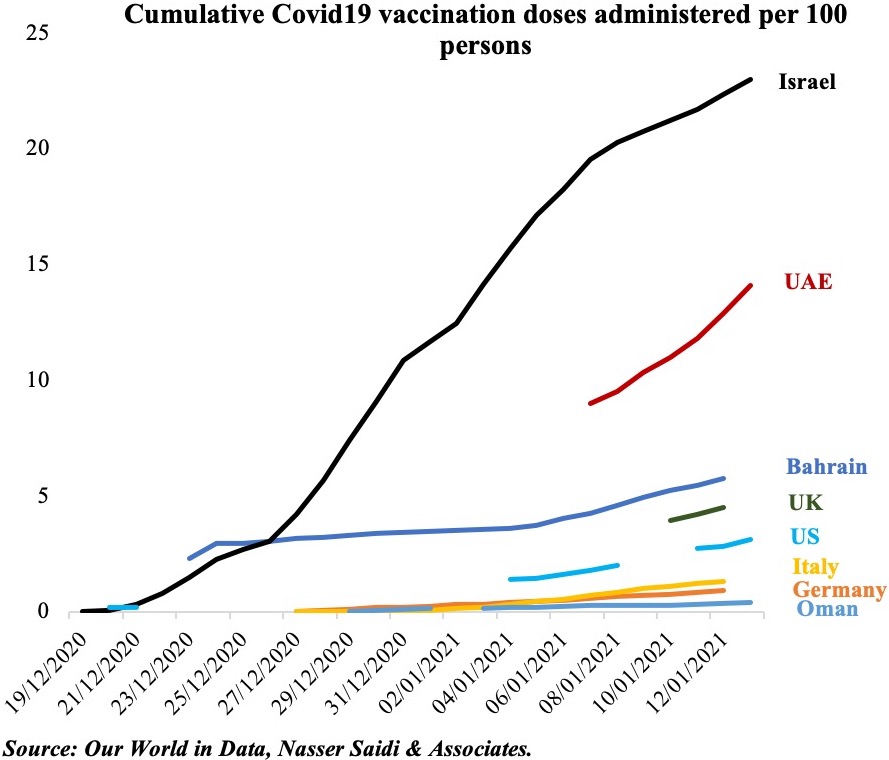

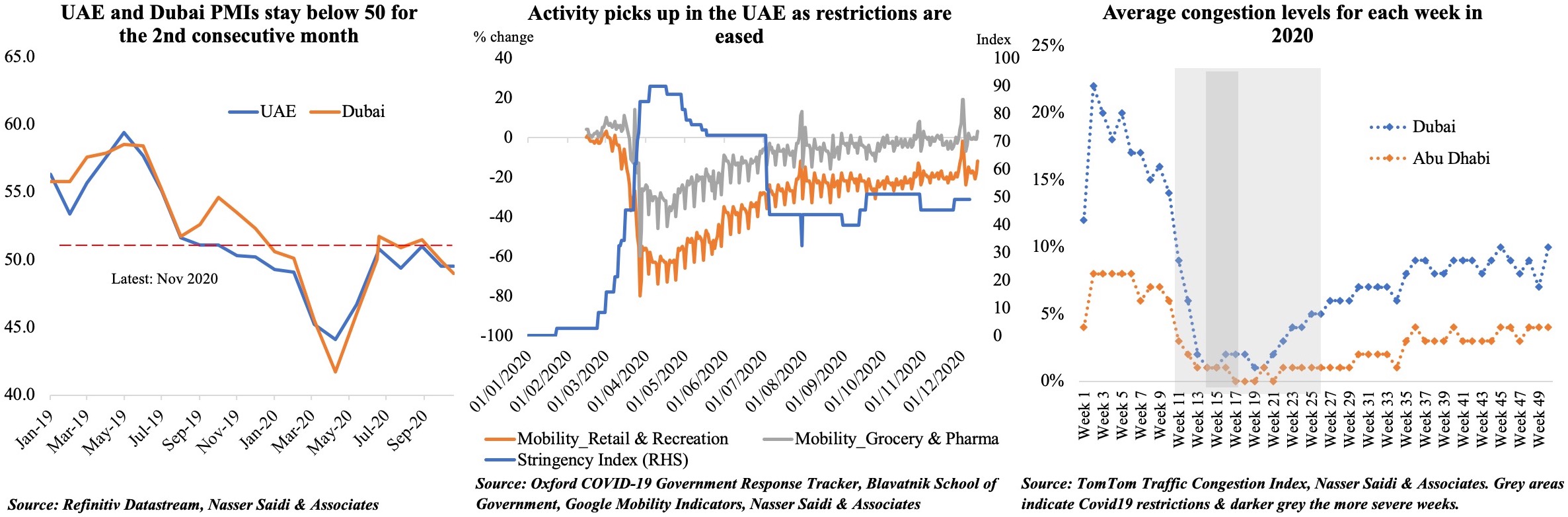

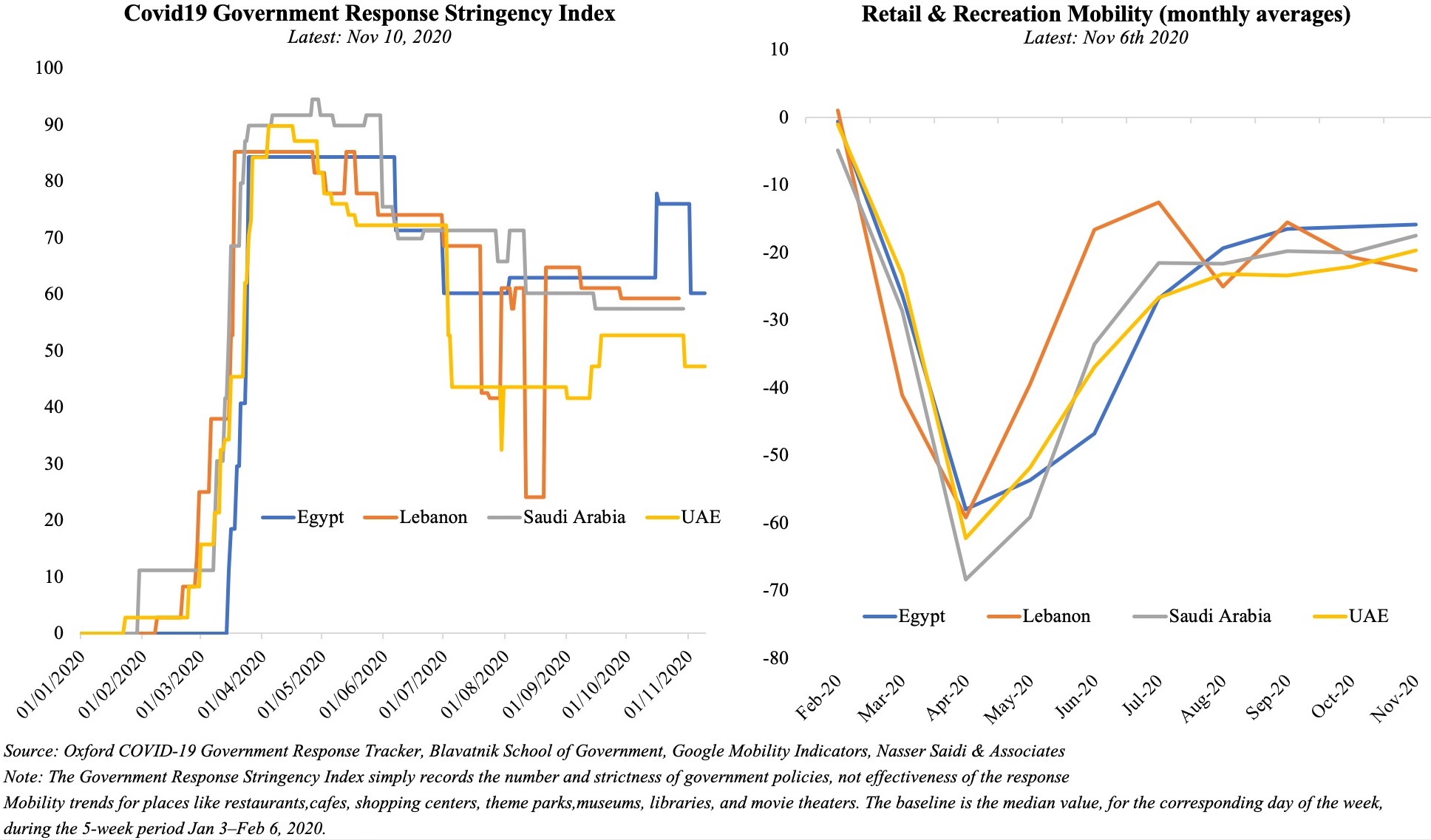

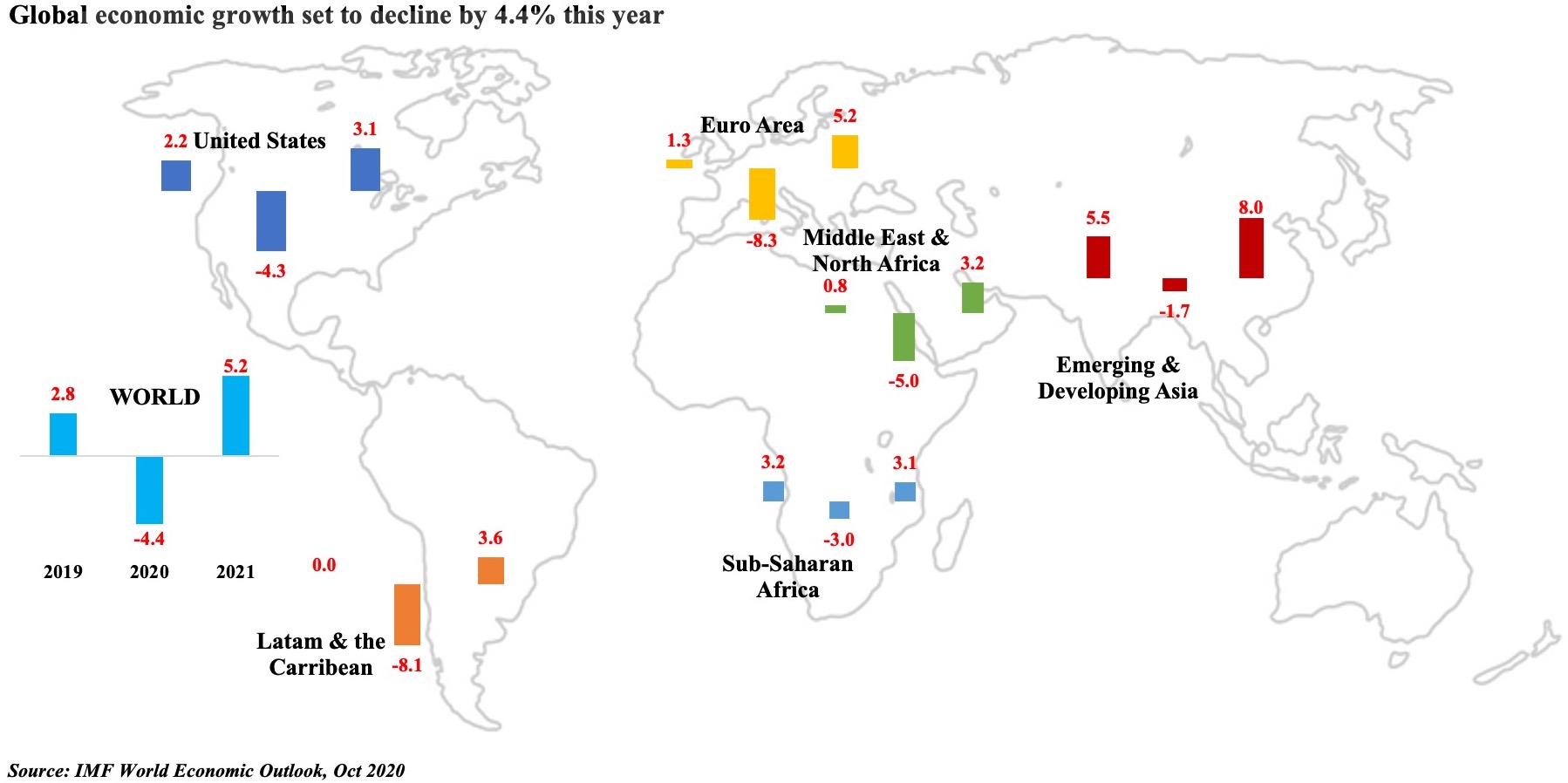

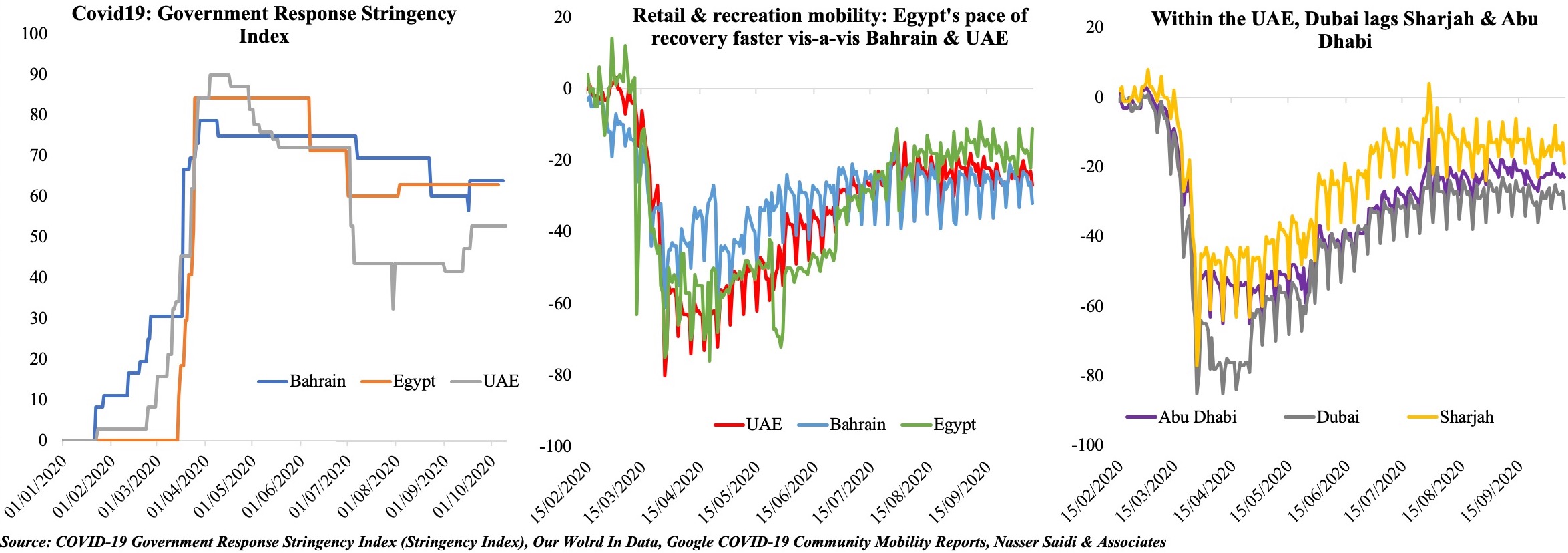

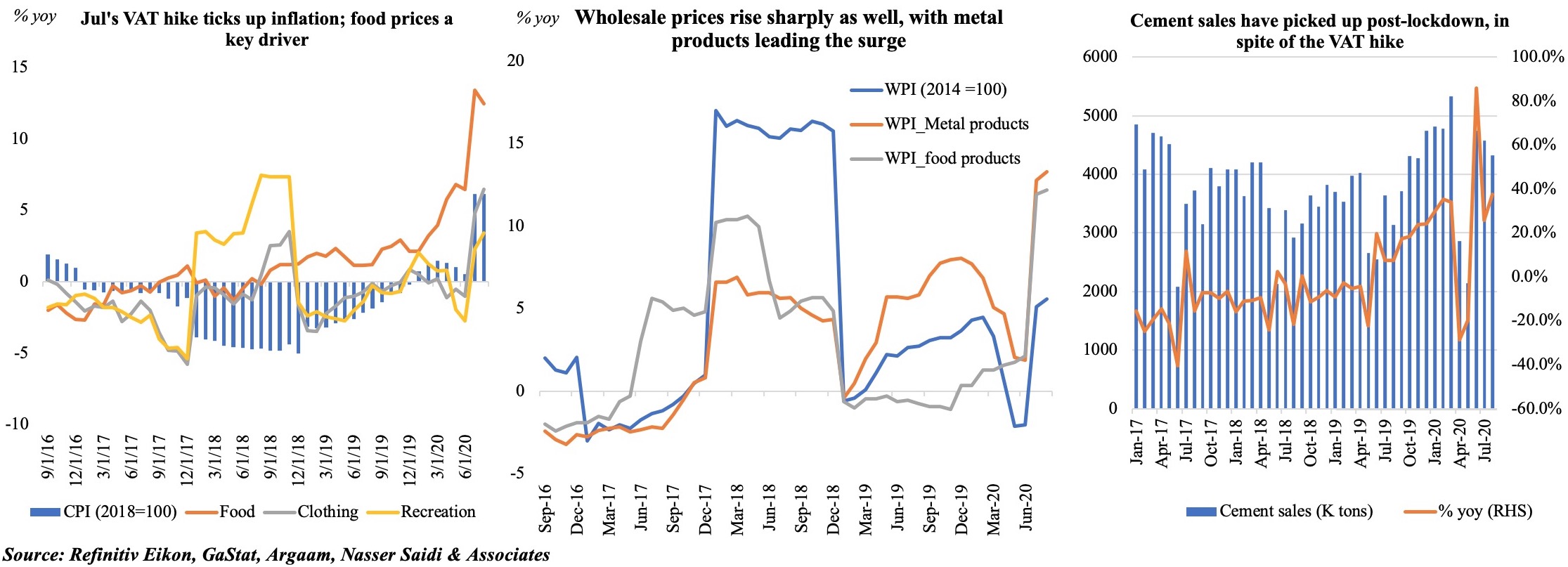

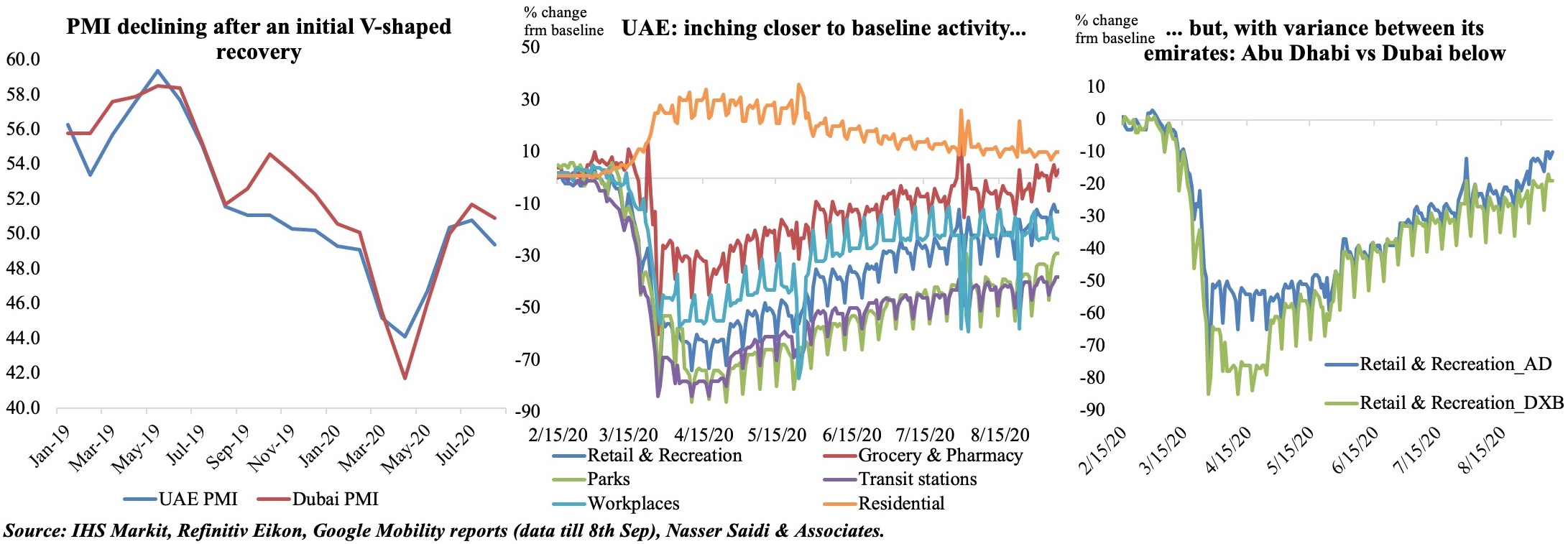

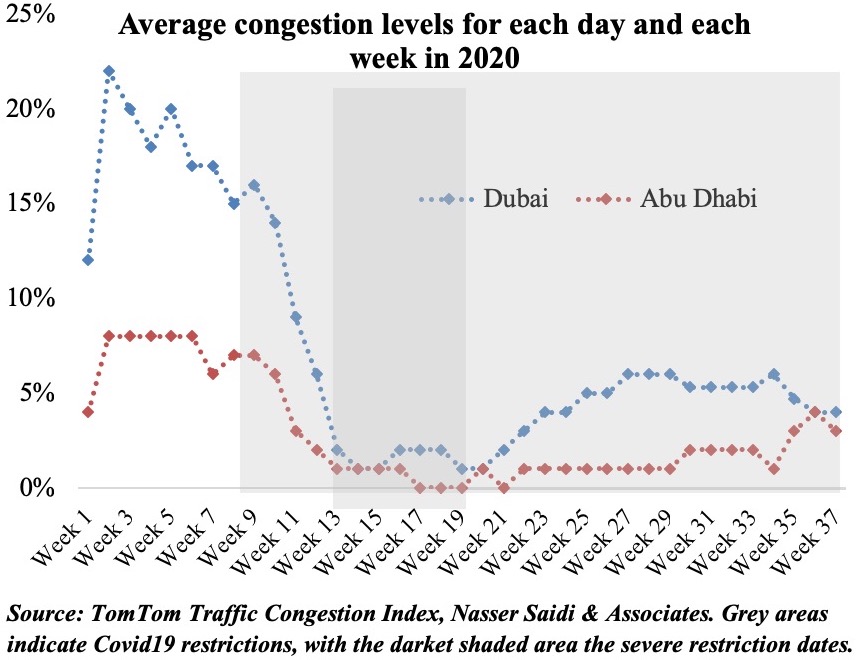

Given the resurgence in Covid19 cases and renewed lockdown measures and the global energy transition away from fossil fuels, it is unlikely that oil prices will revert to the levels seen a few years ago, given weaker demand – the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook puts oil prices, based on futures markets at USD 41.69 in 2020 and USD 46.70 in 2021 (versus an average price of USD 61.39 last year). Fiscal breakeven oil prices in the GCC range between USD 42 for Qatar to USD 104.5 for Oman this year, exerting additional pressure on most oil producers as they ramp up spending to support the economy (UAE’s emirates Dubai and Sharjah announced USD136Mn and USD139Mn respectively in additional stimulus in the last few days).

Given the resurgence in Covid19 cases and renewed lockdown measures and the global energy transition away from fossil fuels, it is unlikely that oil prices will revert to the levels seen a few years ago, given weaker demand – the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook puts oil prices, based on futures markets at USD 41.69 in 2020 and USD 46.70 in 2021 (versus an average price of USD 61.39 last year). Fiscal breakeven oil prices in the GCC range between USD 42 for Qatar to USD 104.5 for Oman this year, exerting additional pressure on most oil producers as they ramp up spending to support the economy (UAE’s emirates Dubai and Sharjah announced USD136Mn and USD139Mn respectively in additional stimulus in the last few days).

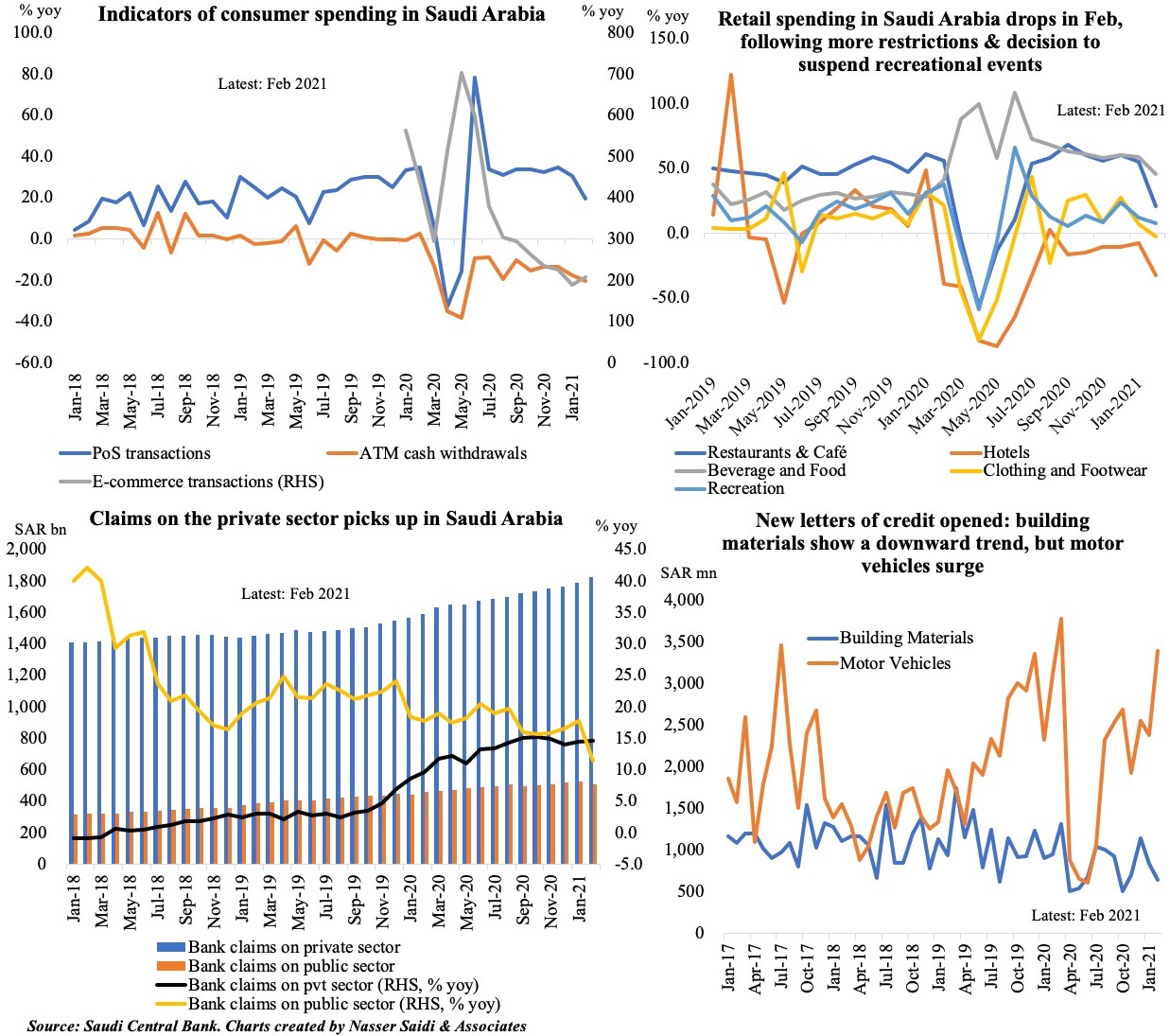

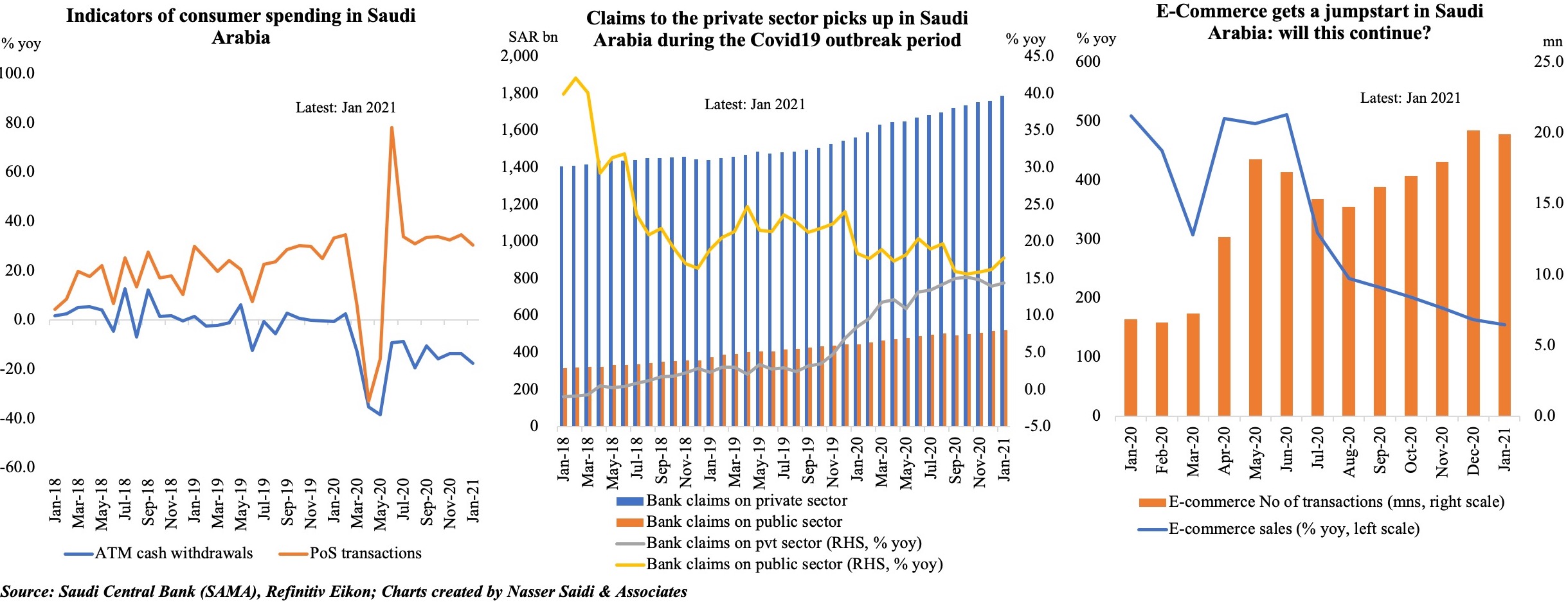

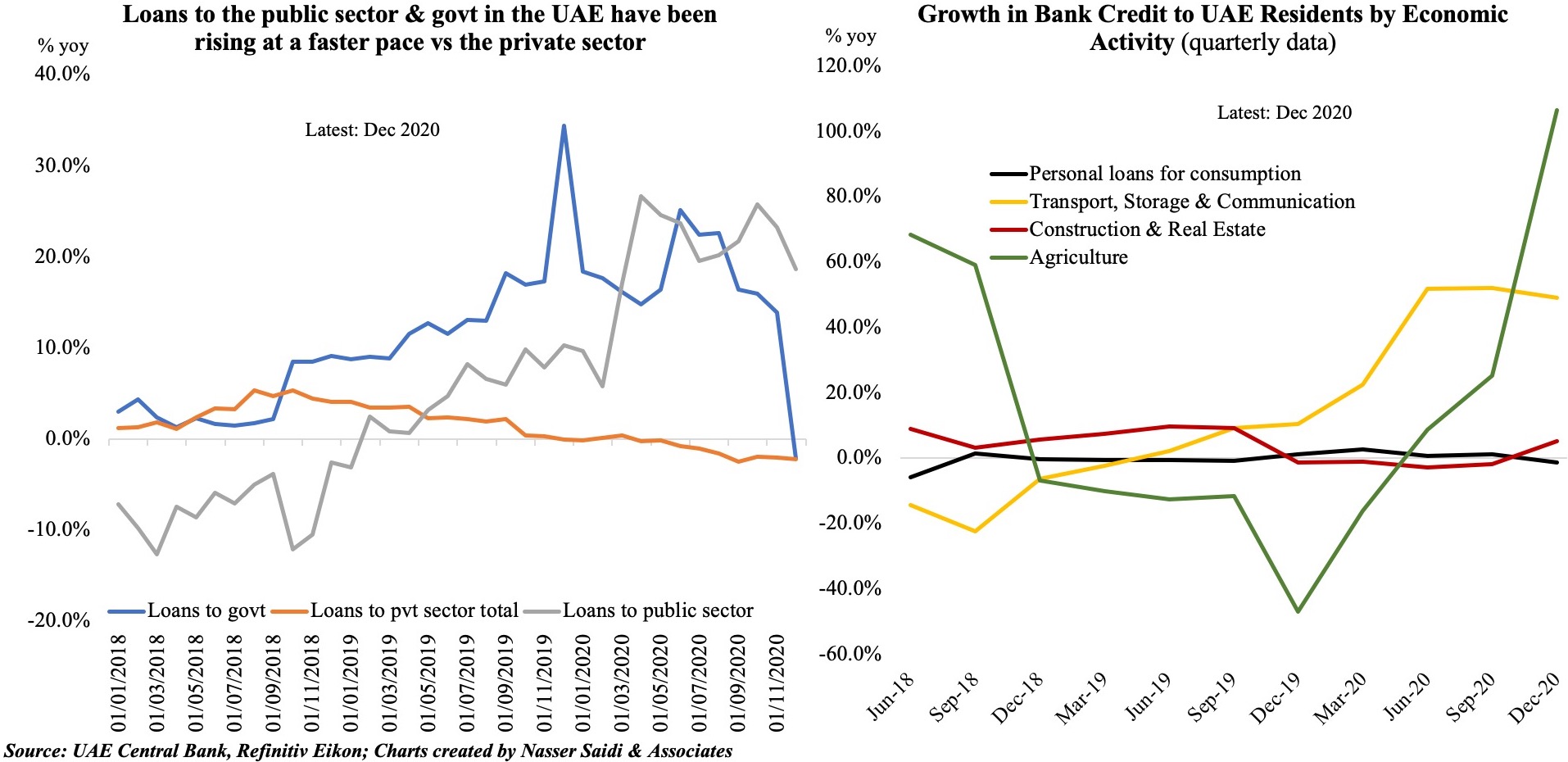

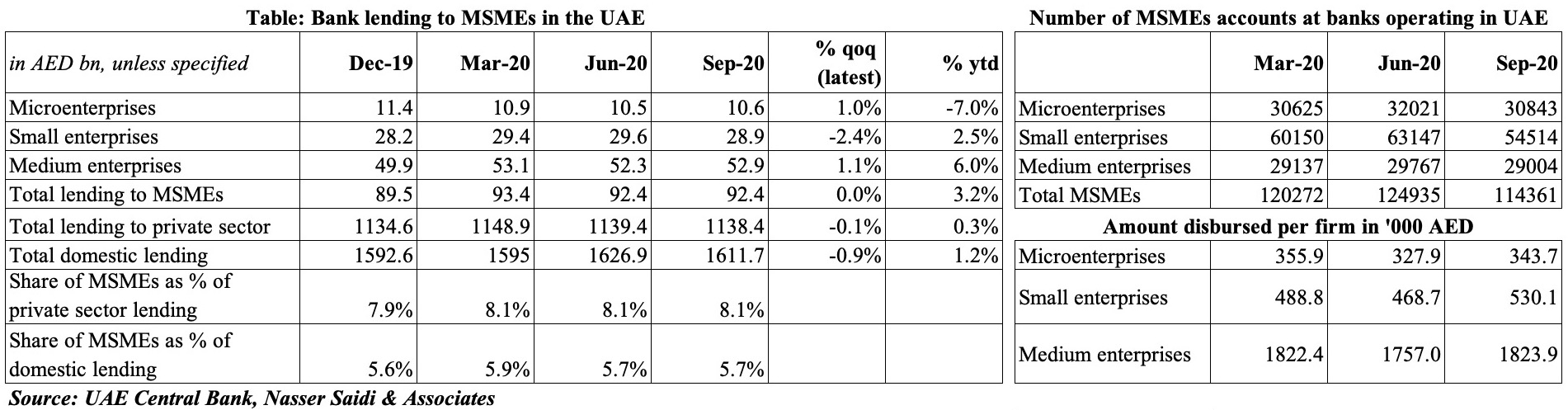

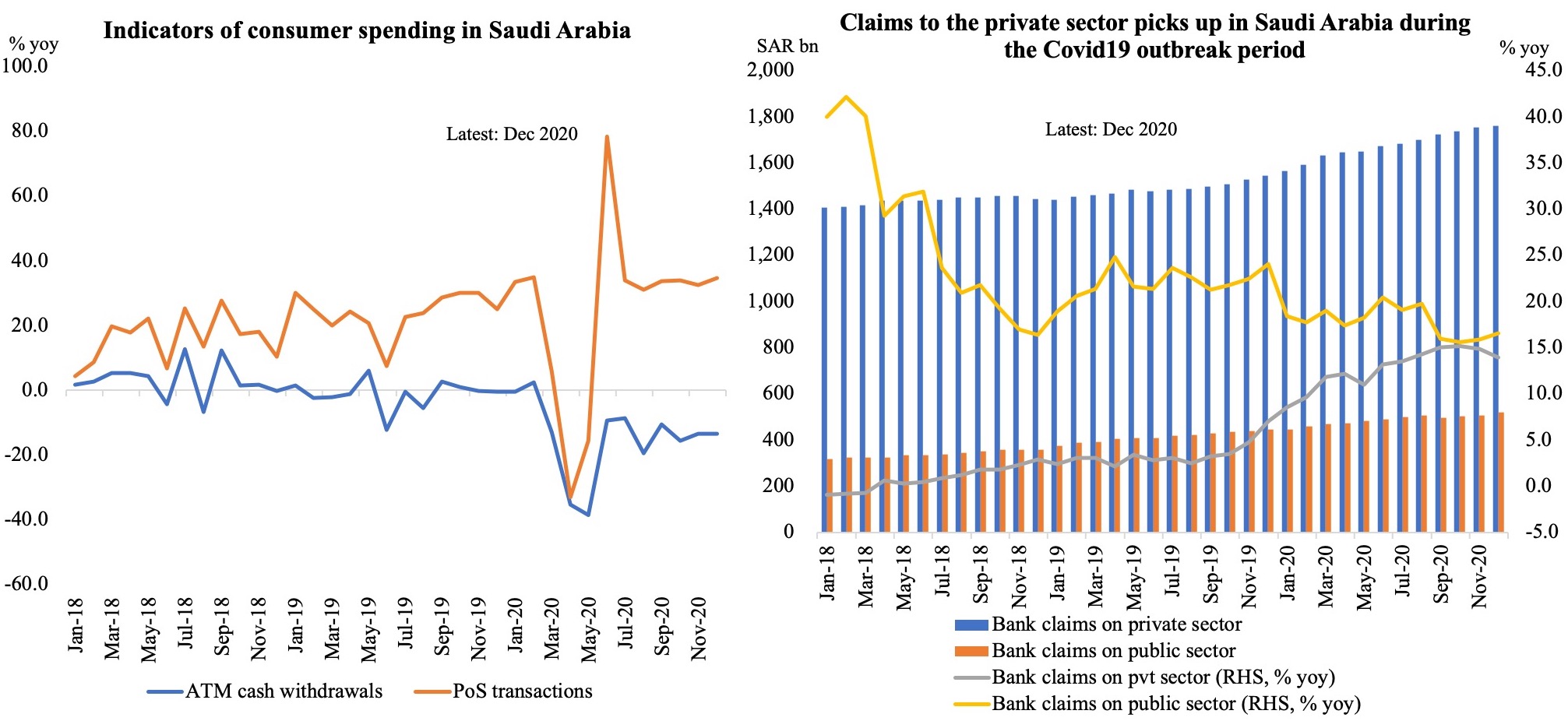

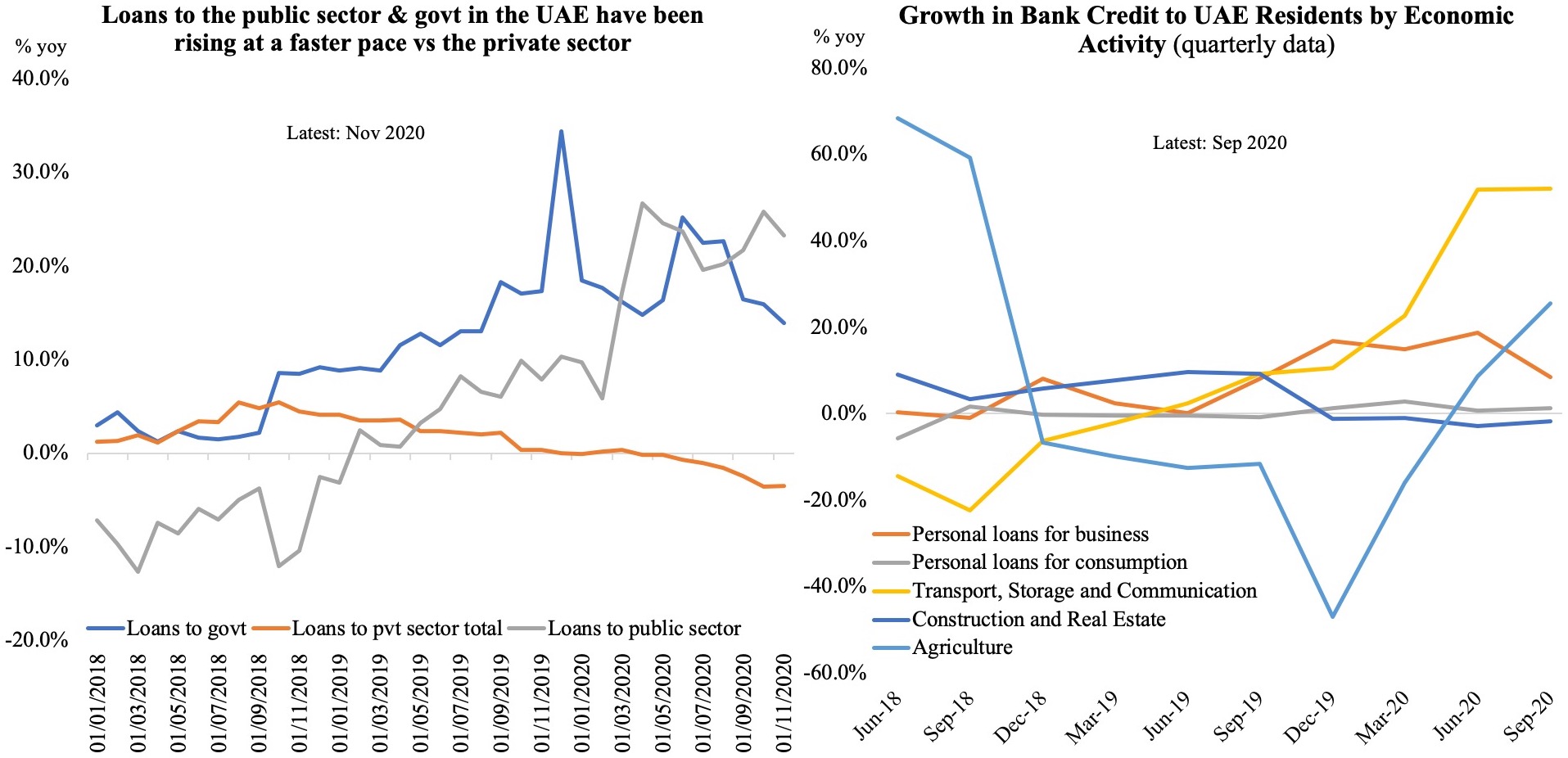

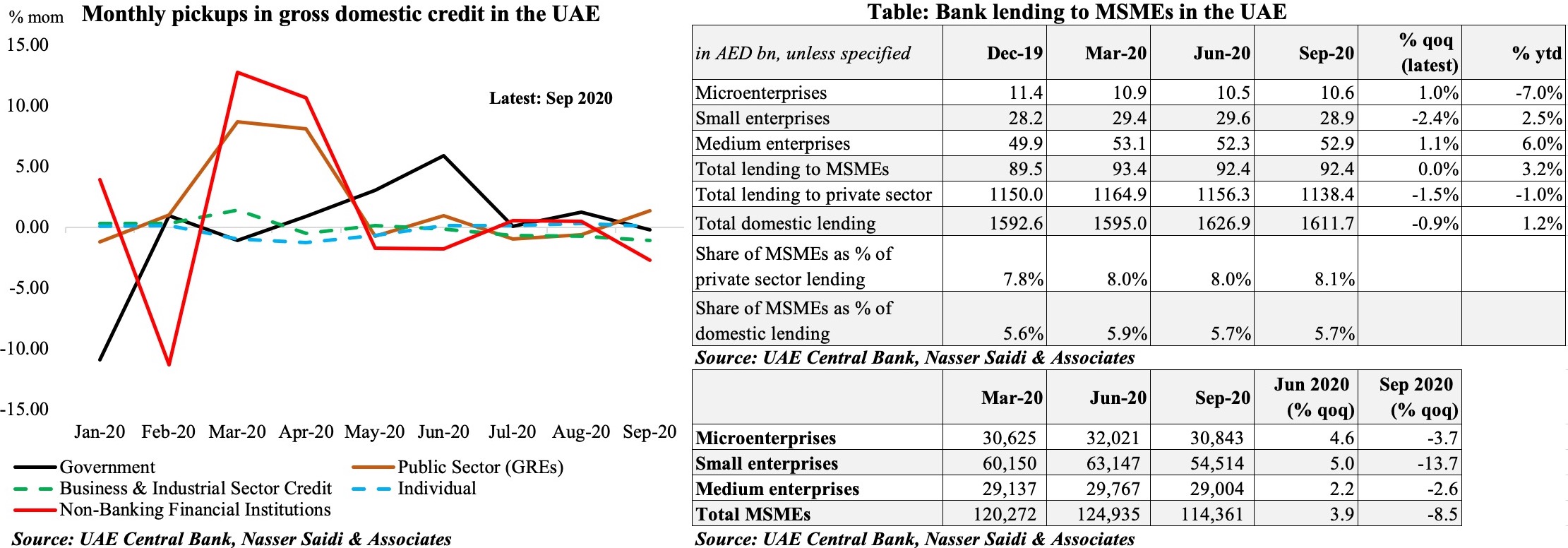

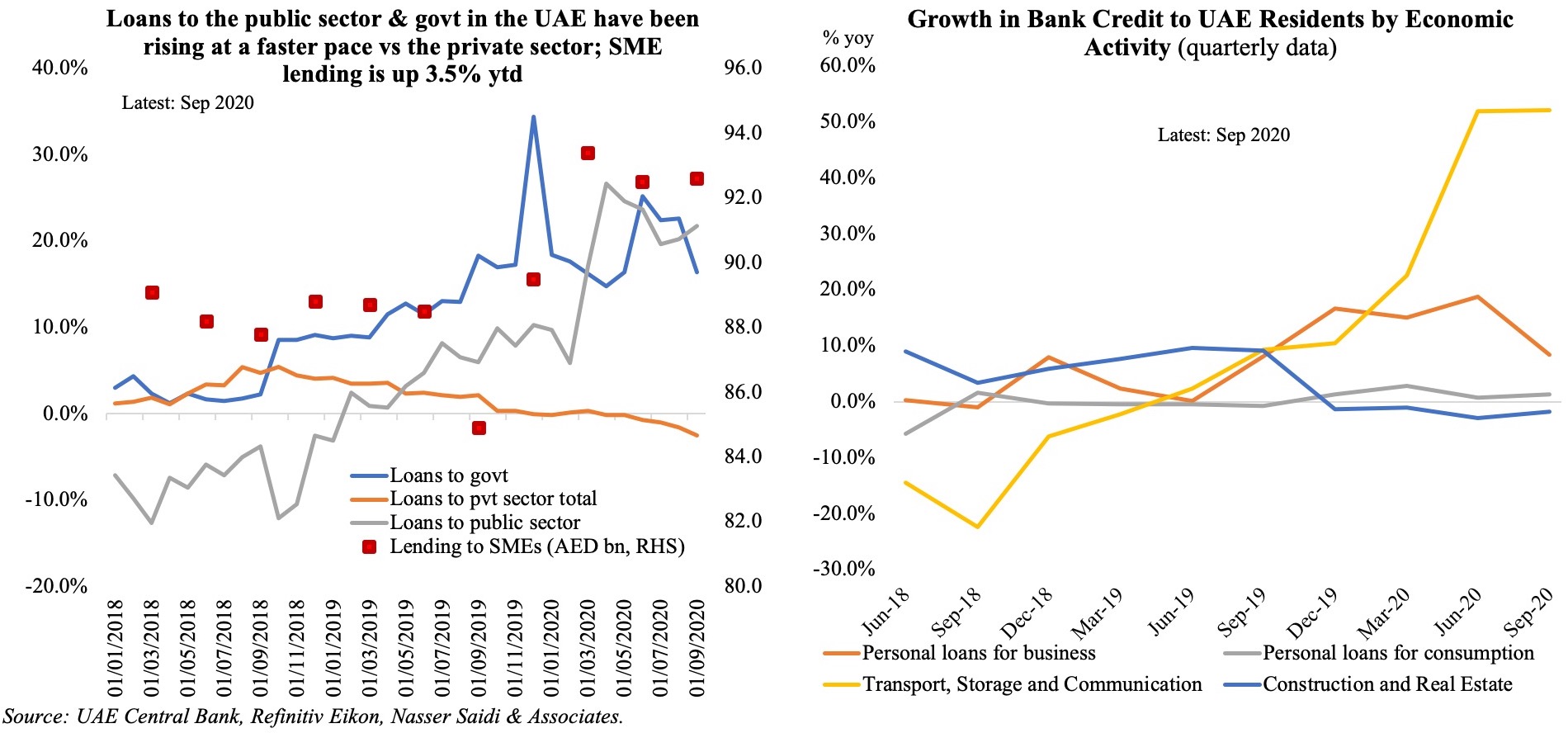

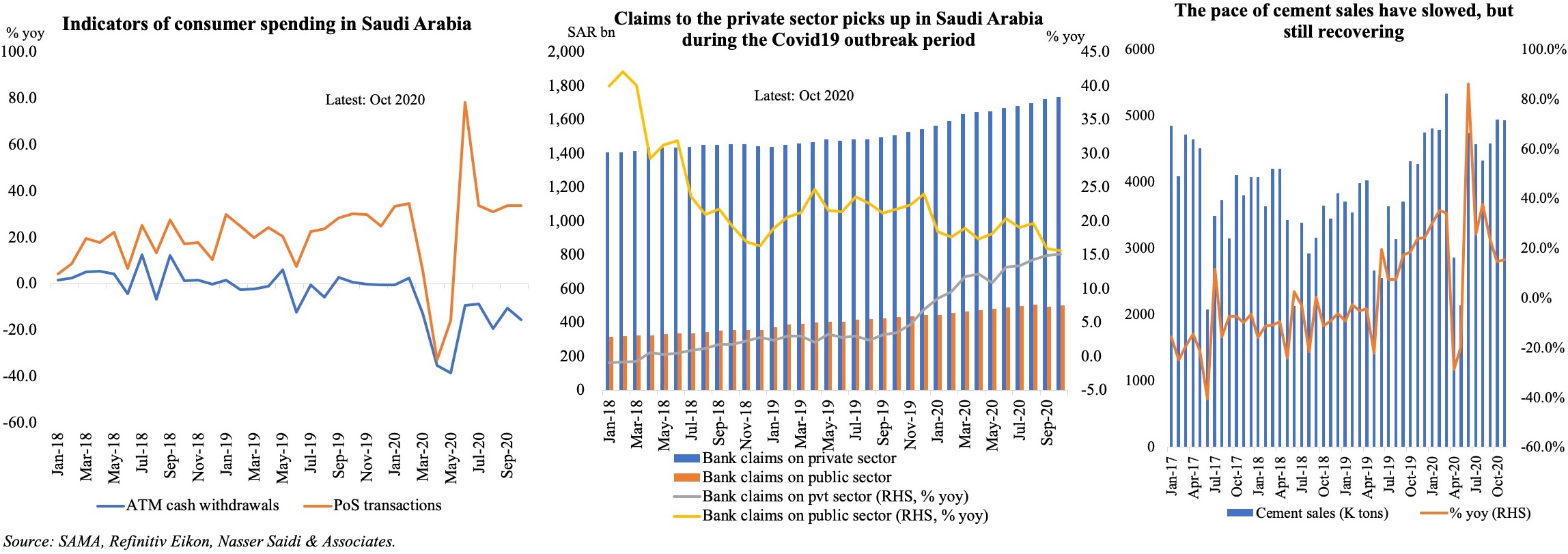

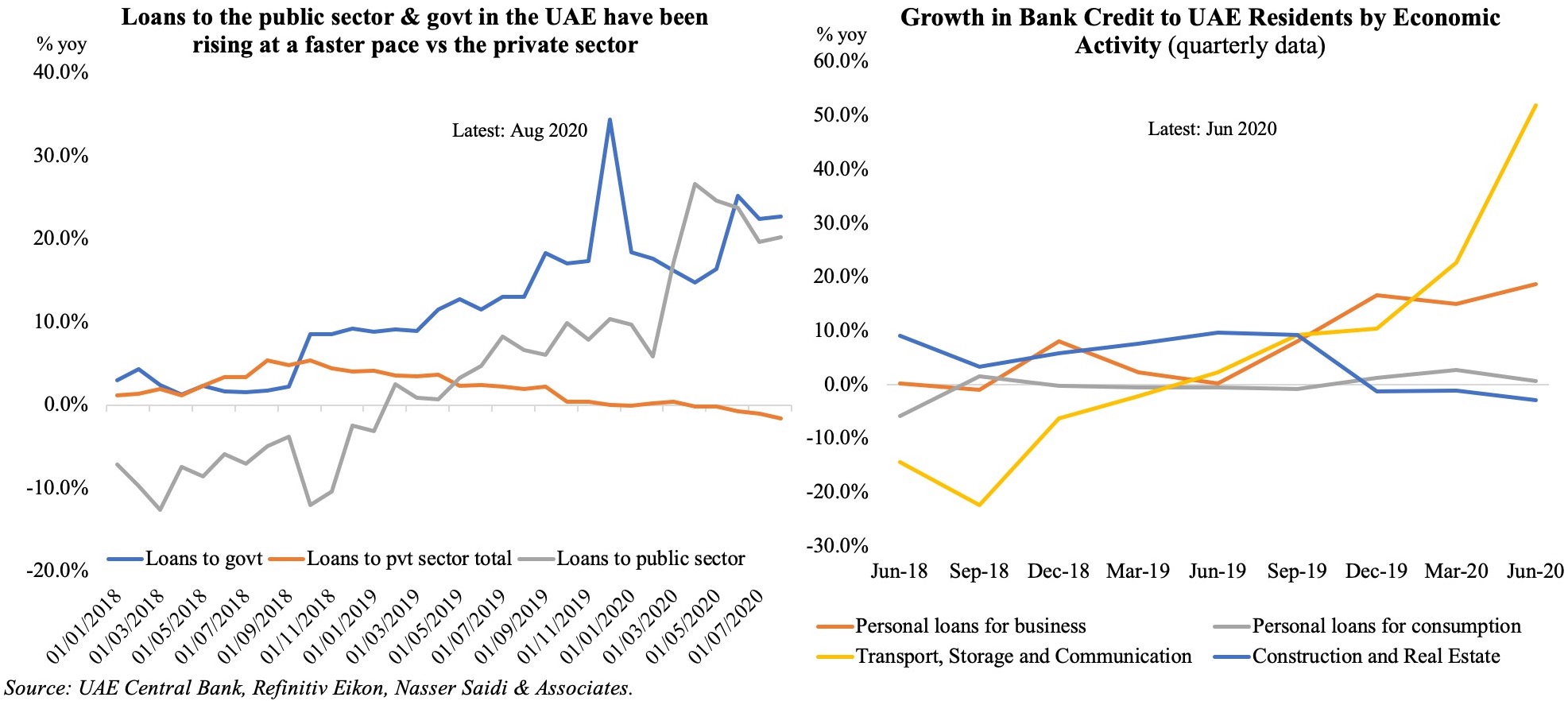

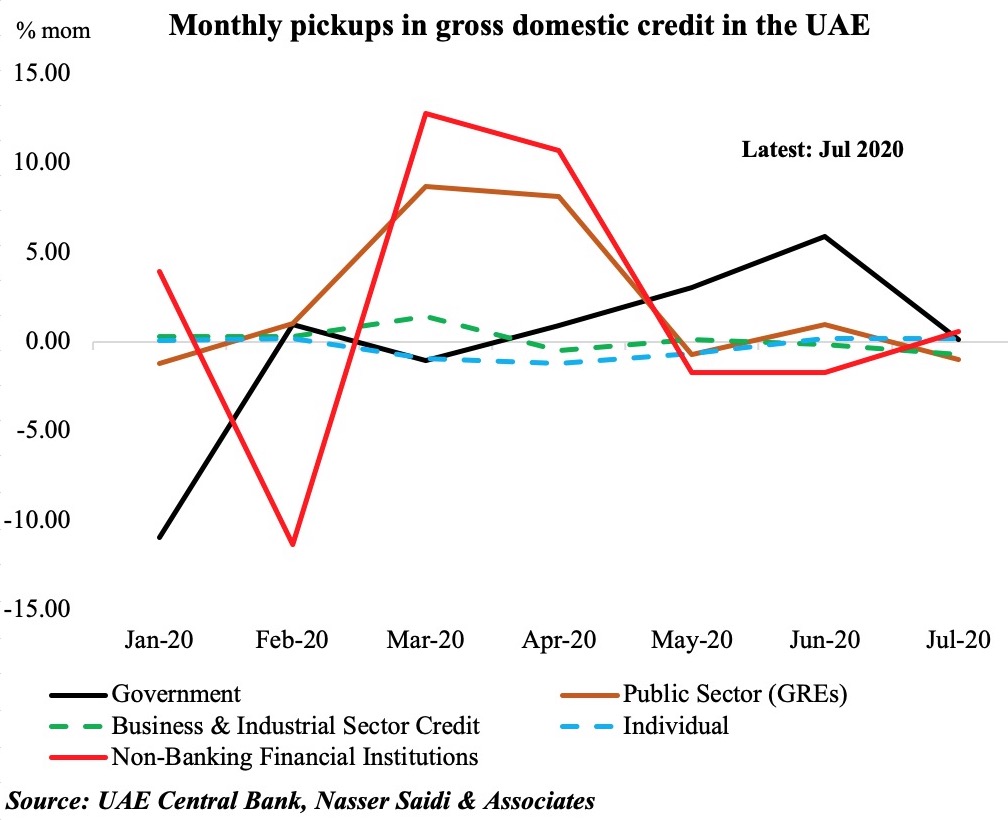

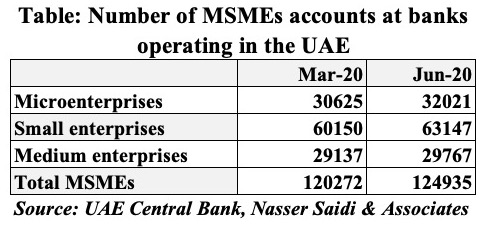

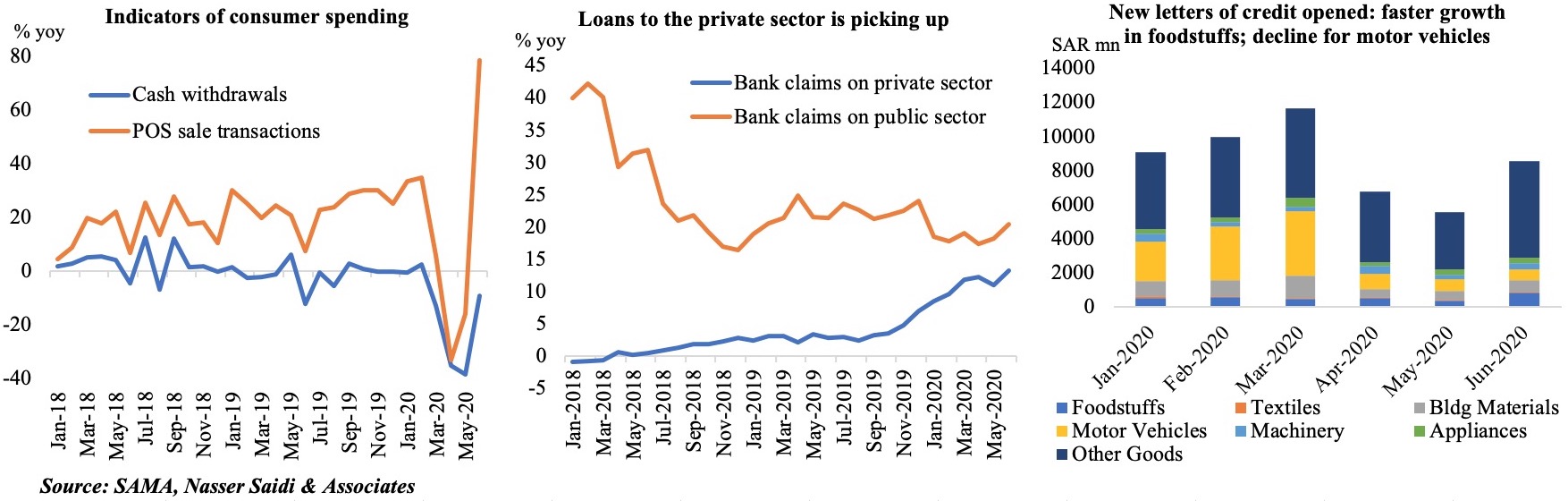

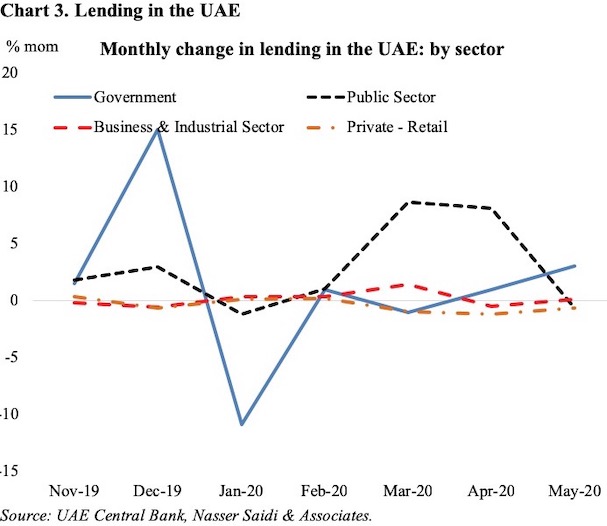

ral bank shed some light on the broader credit movements: the accompanying chart shows the monthly changes in gross domestic credit. The dotted lines are credit to businesses and individuals (the private sector) which show no substantial increases – in fact, it increased by an average 0.9% year-to-date (ytd) for businesses and dropped by 2.1% ytd for individuals. The uptick in lending to the public sector (government related entities) and government have been discussed previously

ral bank shed some light on the broader credit movements: the accompanying chart shows the monthly changes in gross domestic credit. The dotted lines are credit to businesses and individuals (the private sector) which show no substantial increases – in fact, it increased by an average 0.9% year-to-date (ytd) for businesses and dropped by 2.1% ytd for individuals. The uptick in lending to the public sector (government related entities) and government have been discussed previously

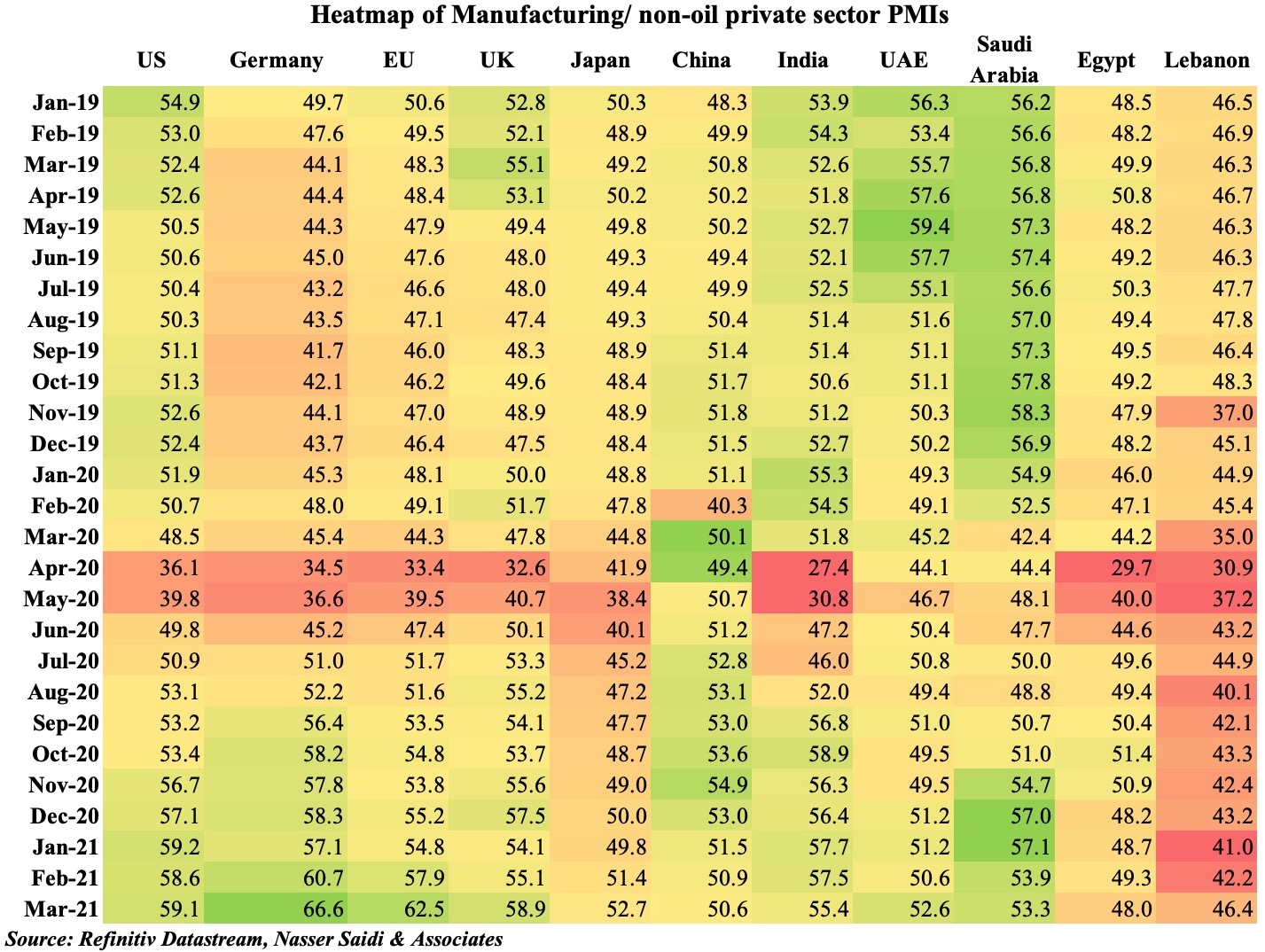

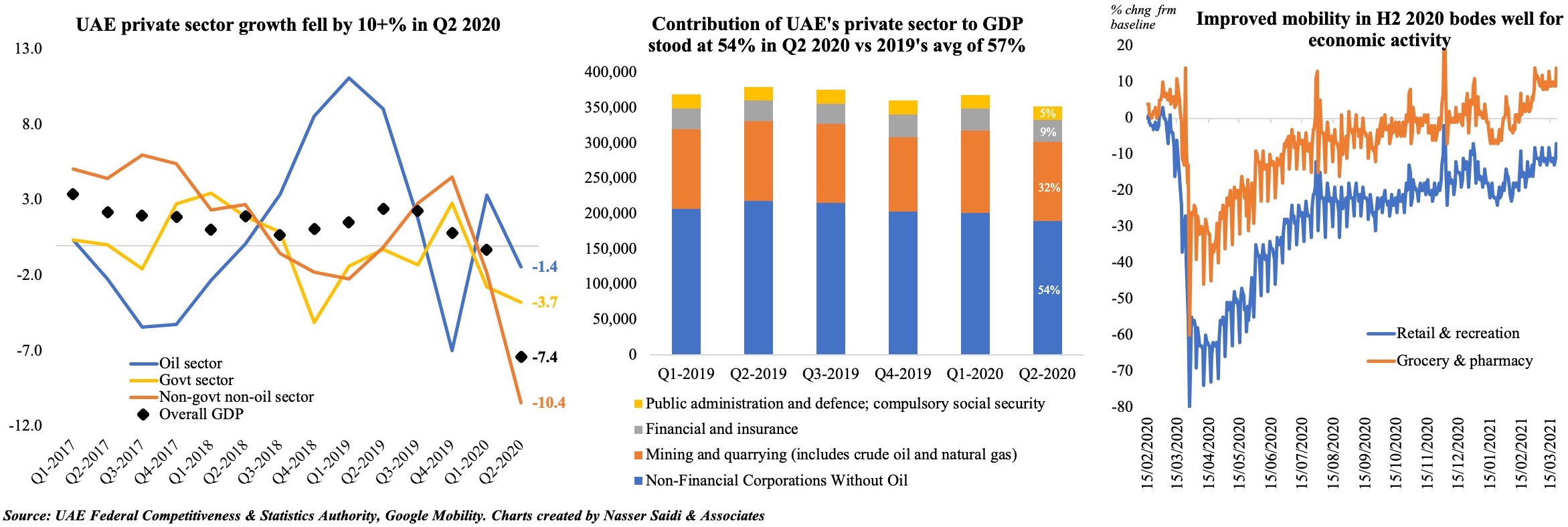

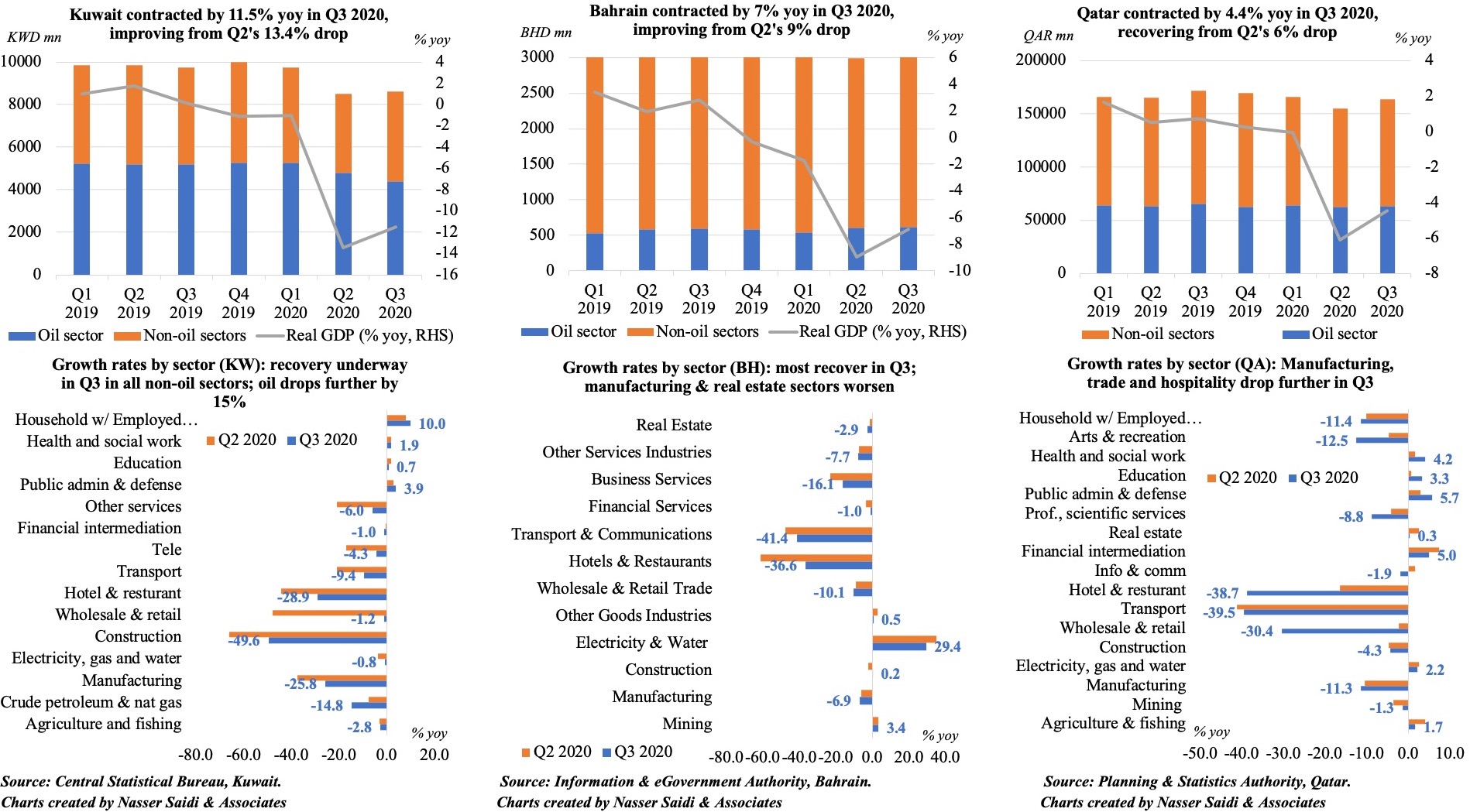

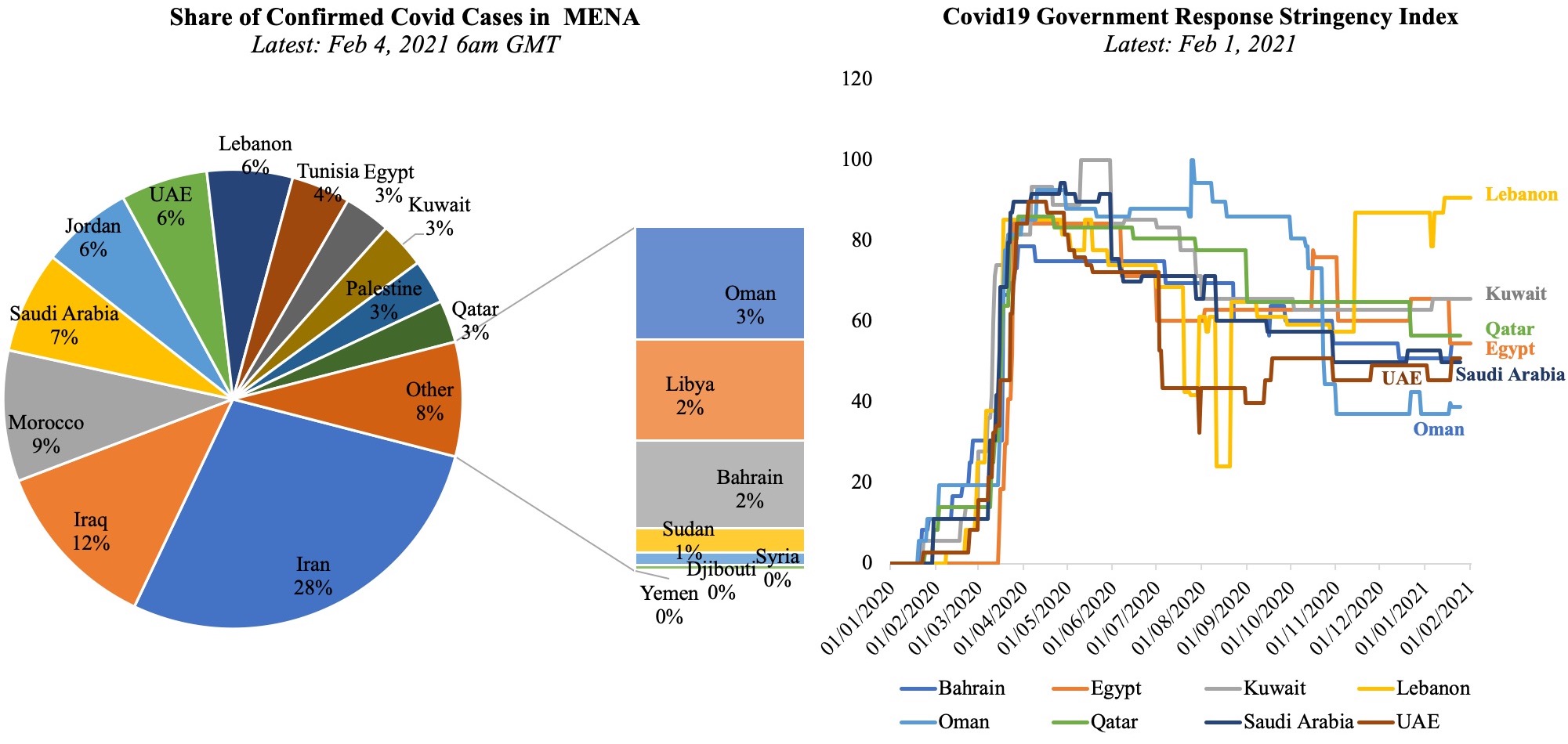

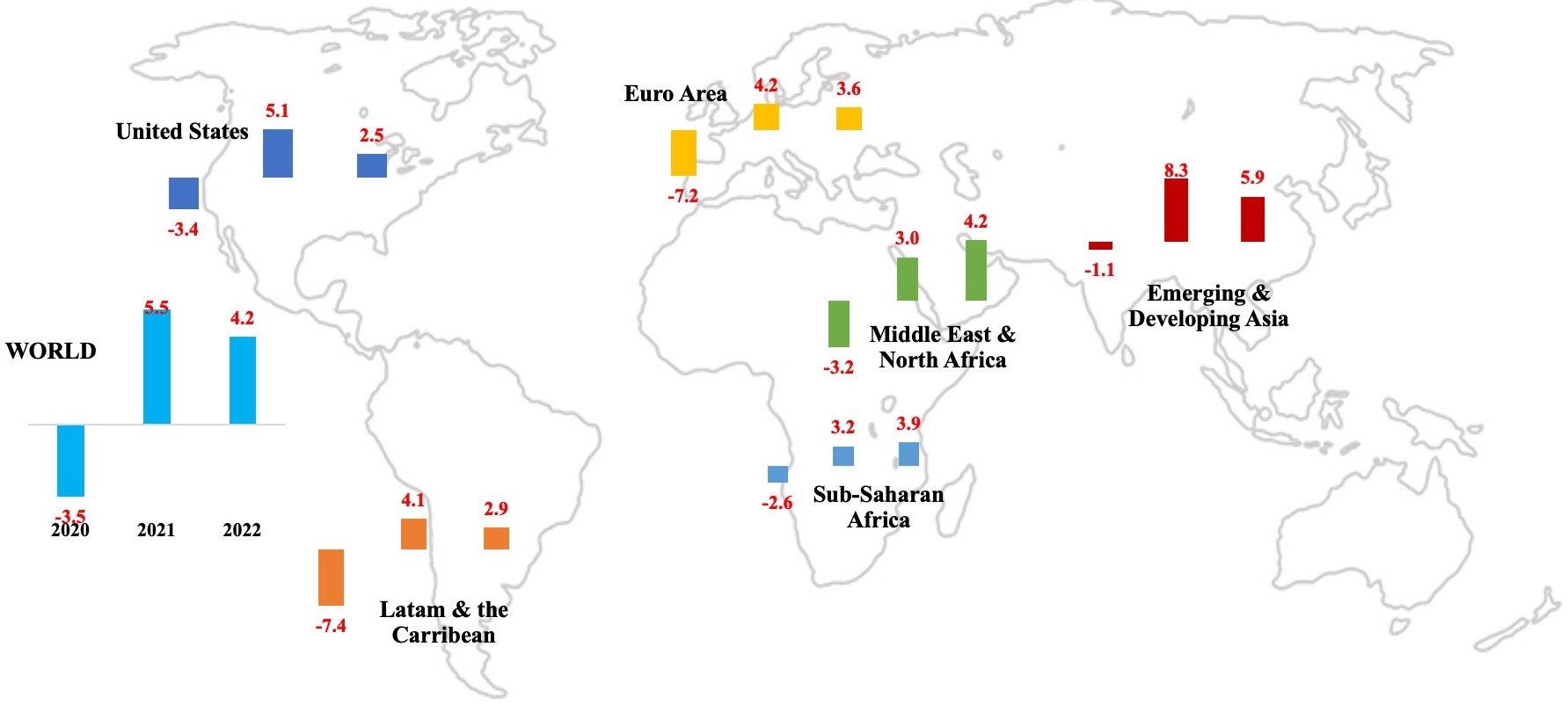

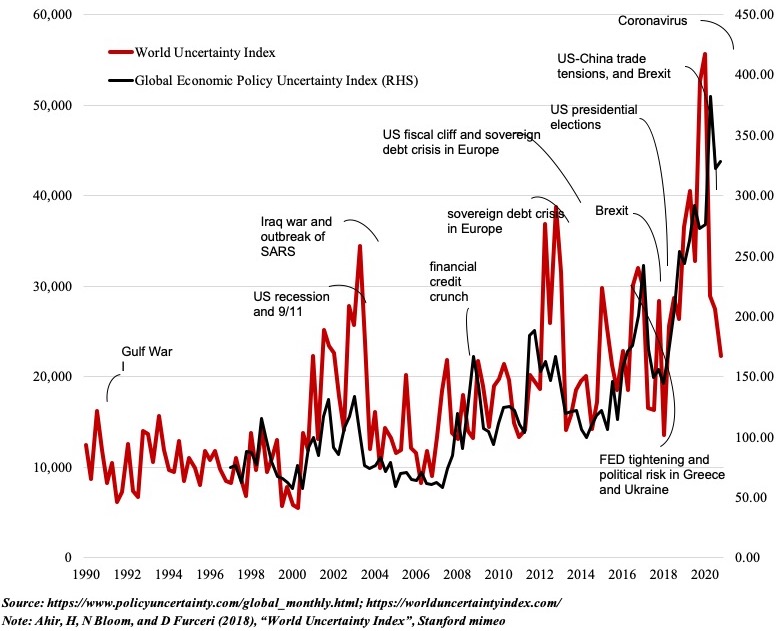

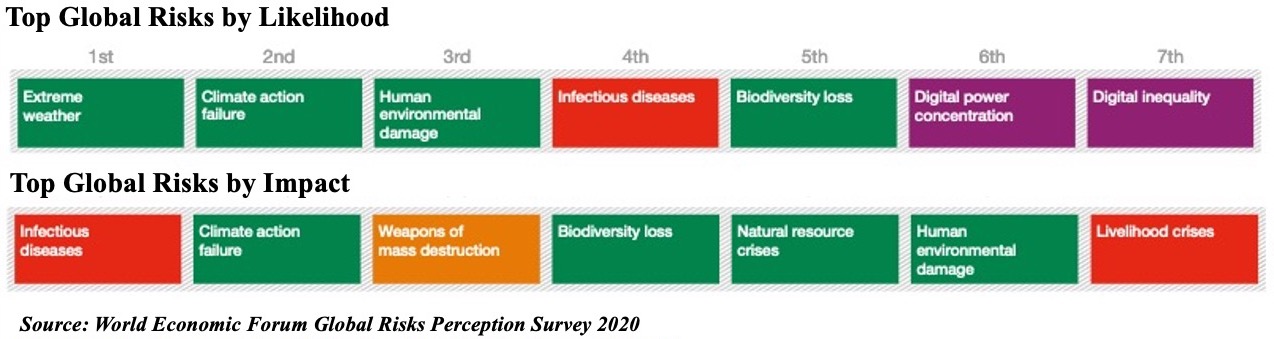

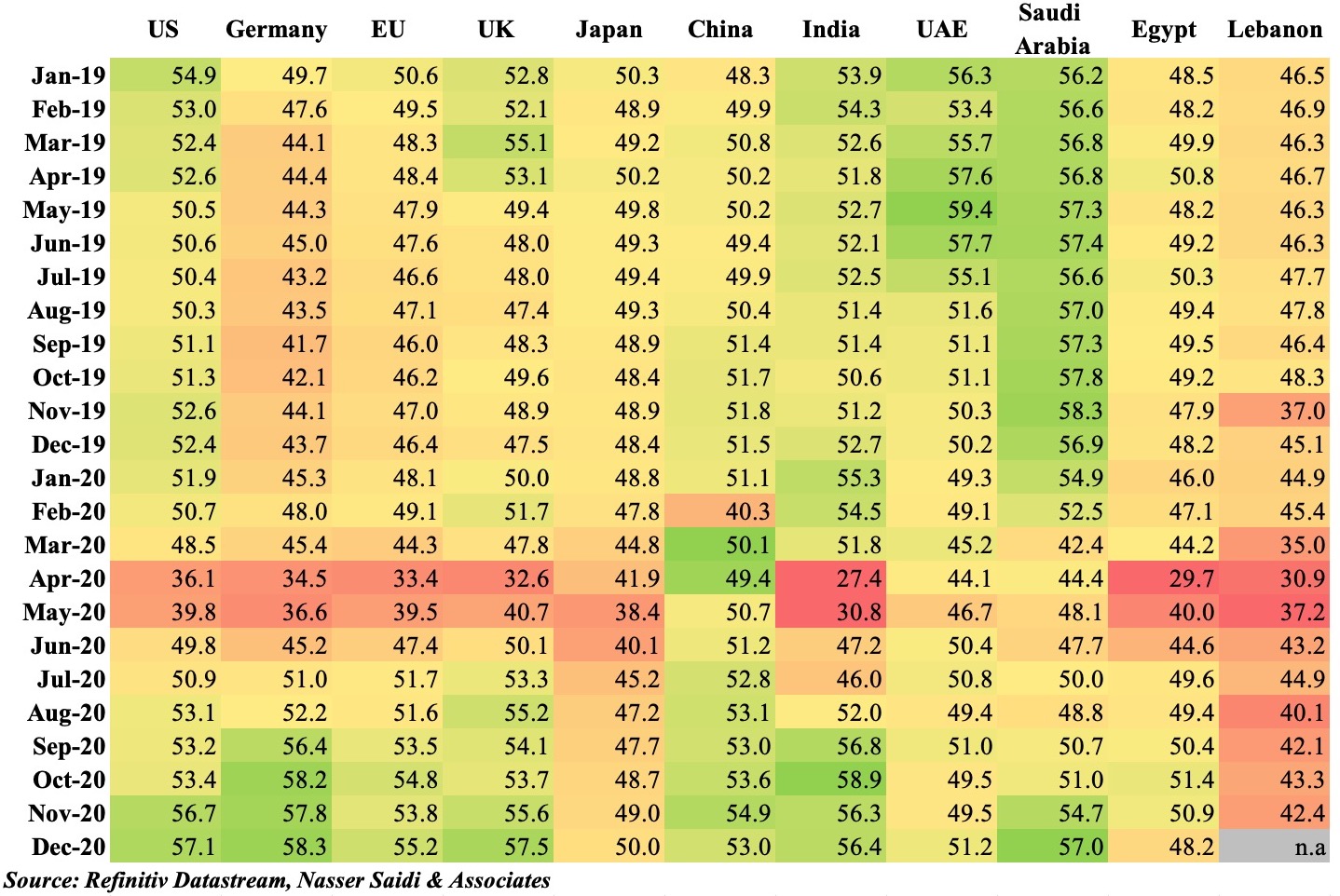

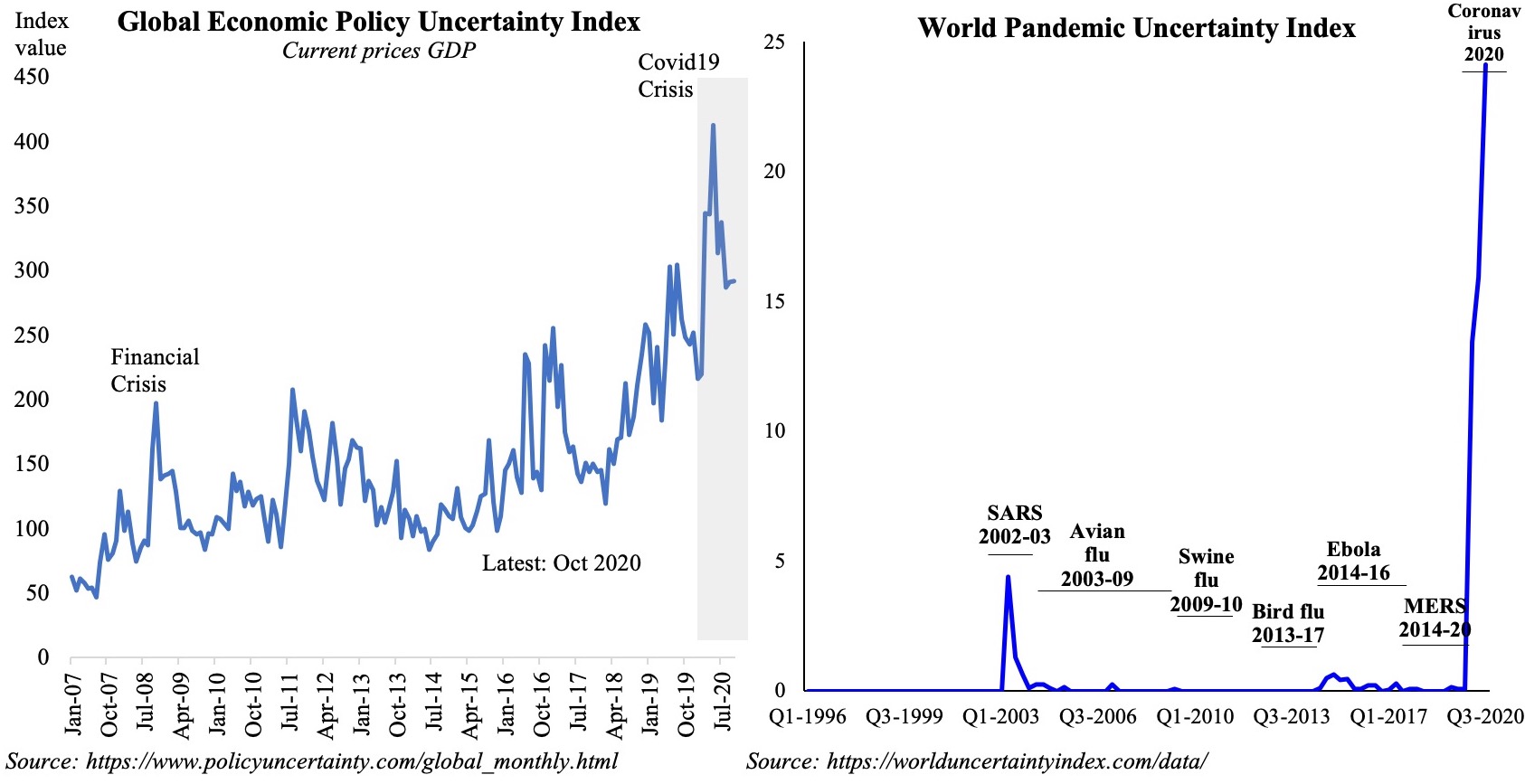

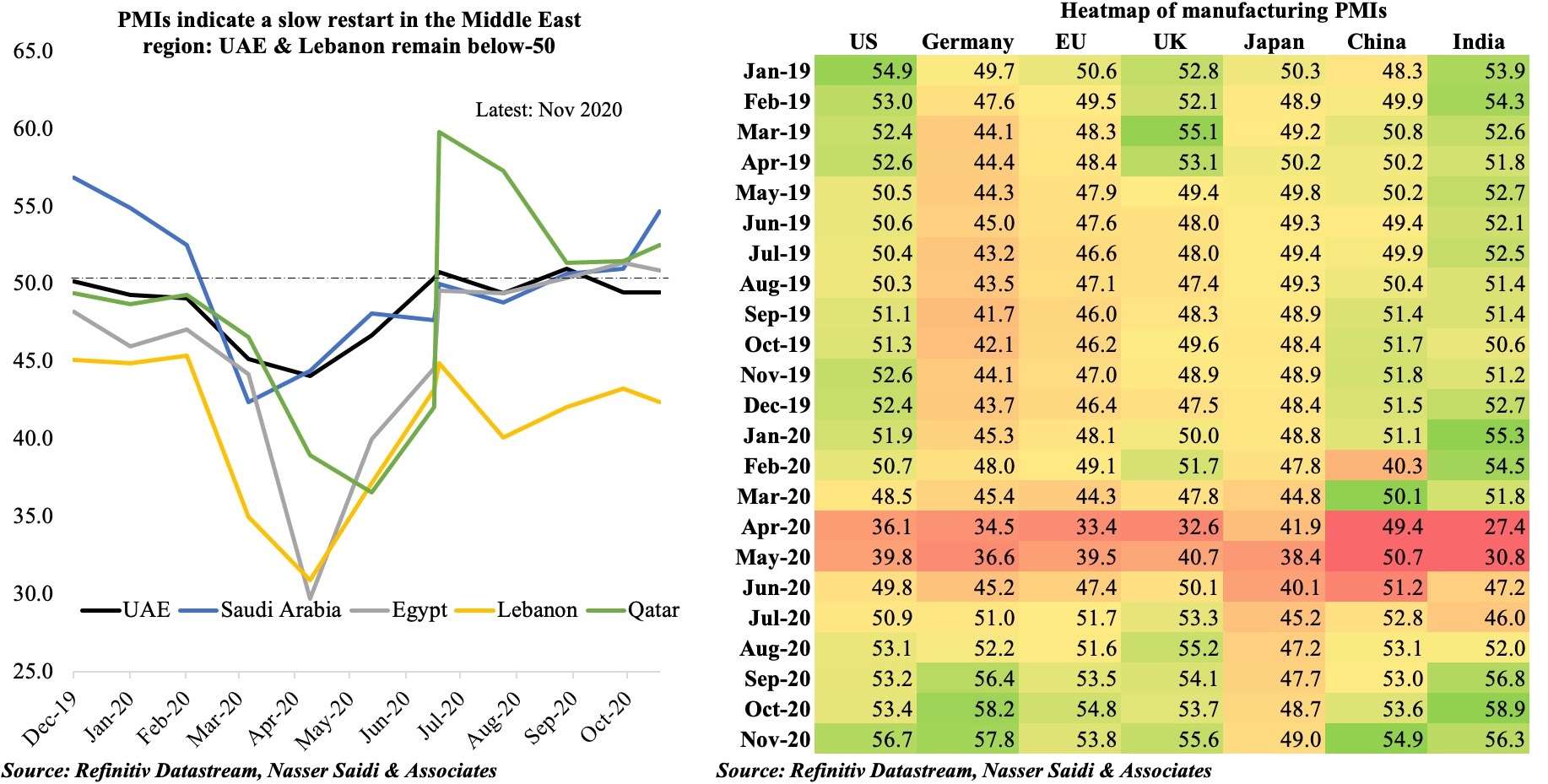

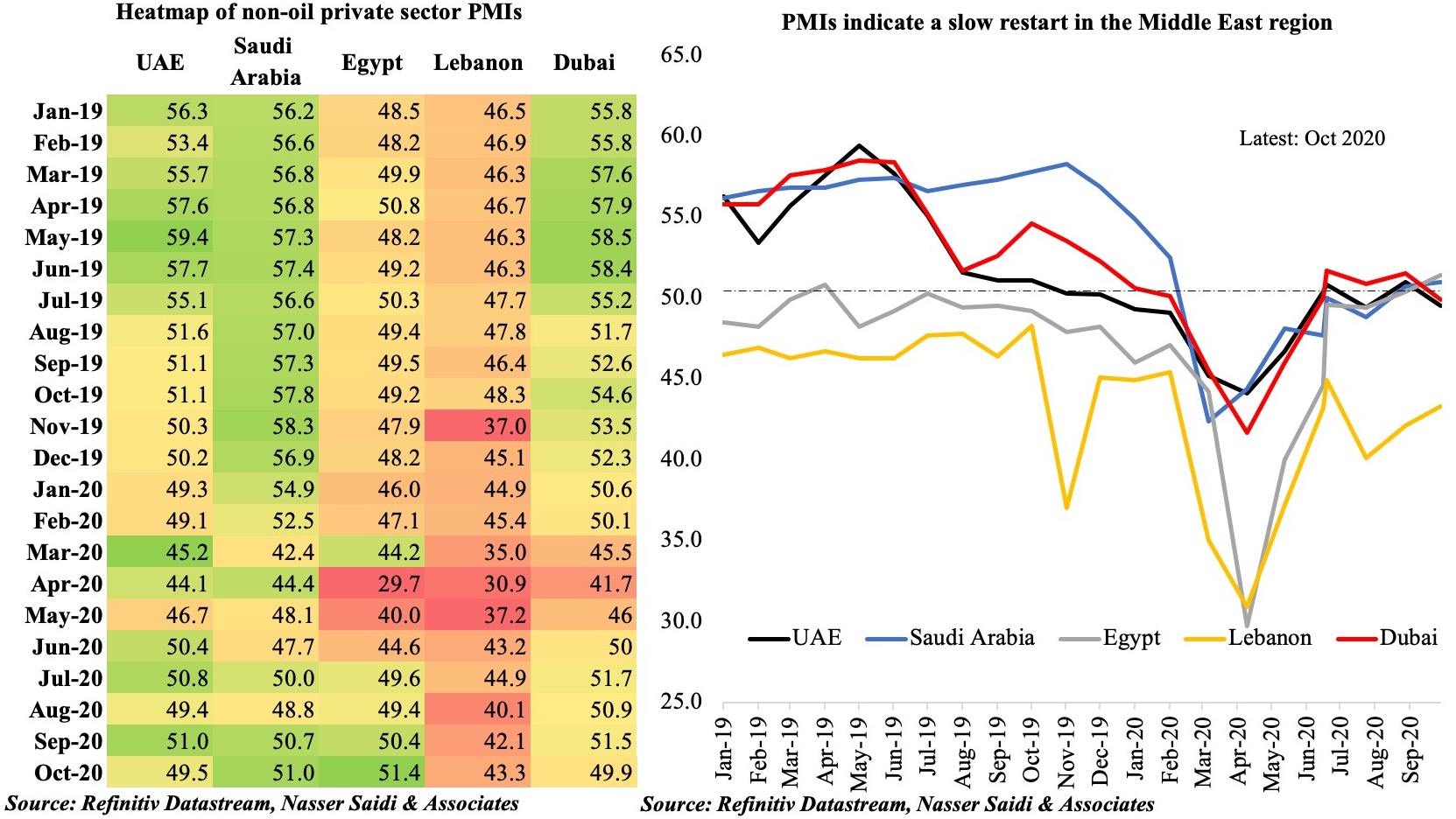

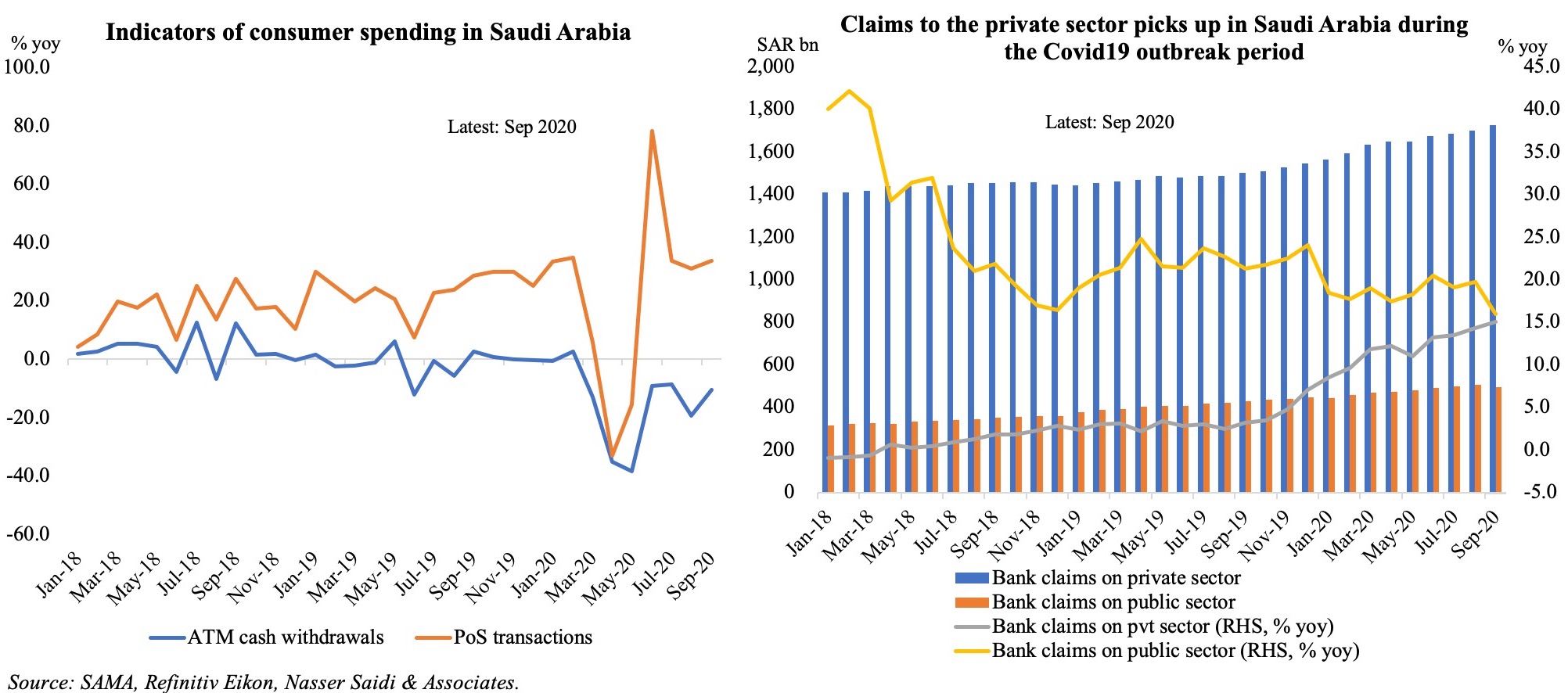

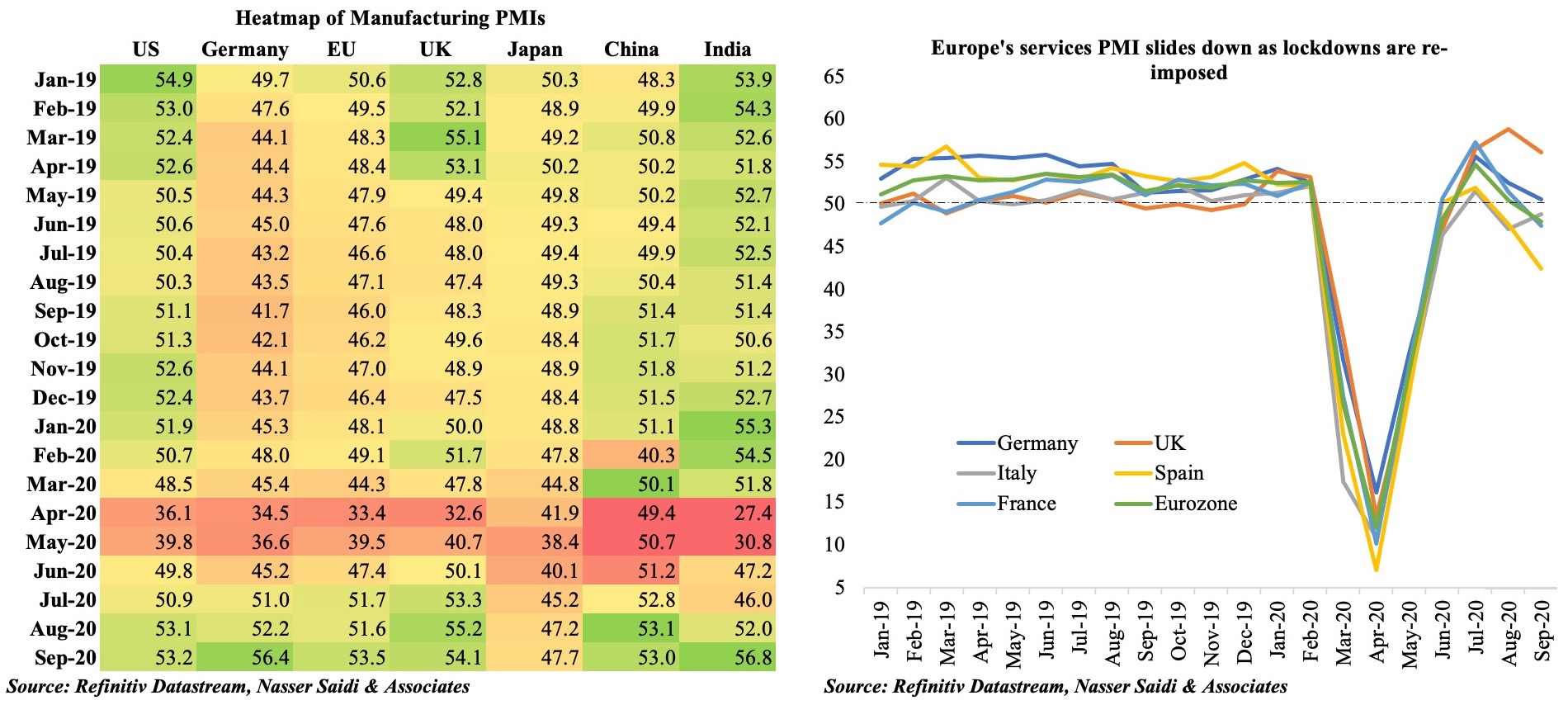

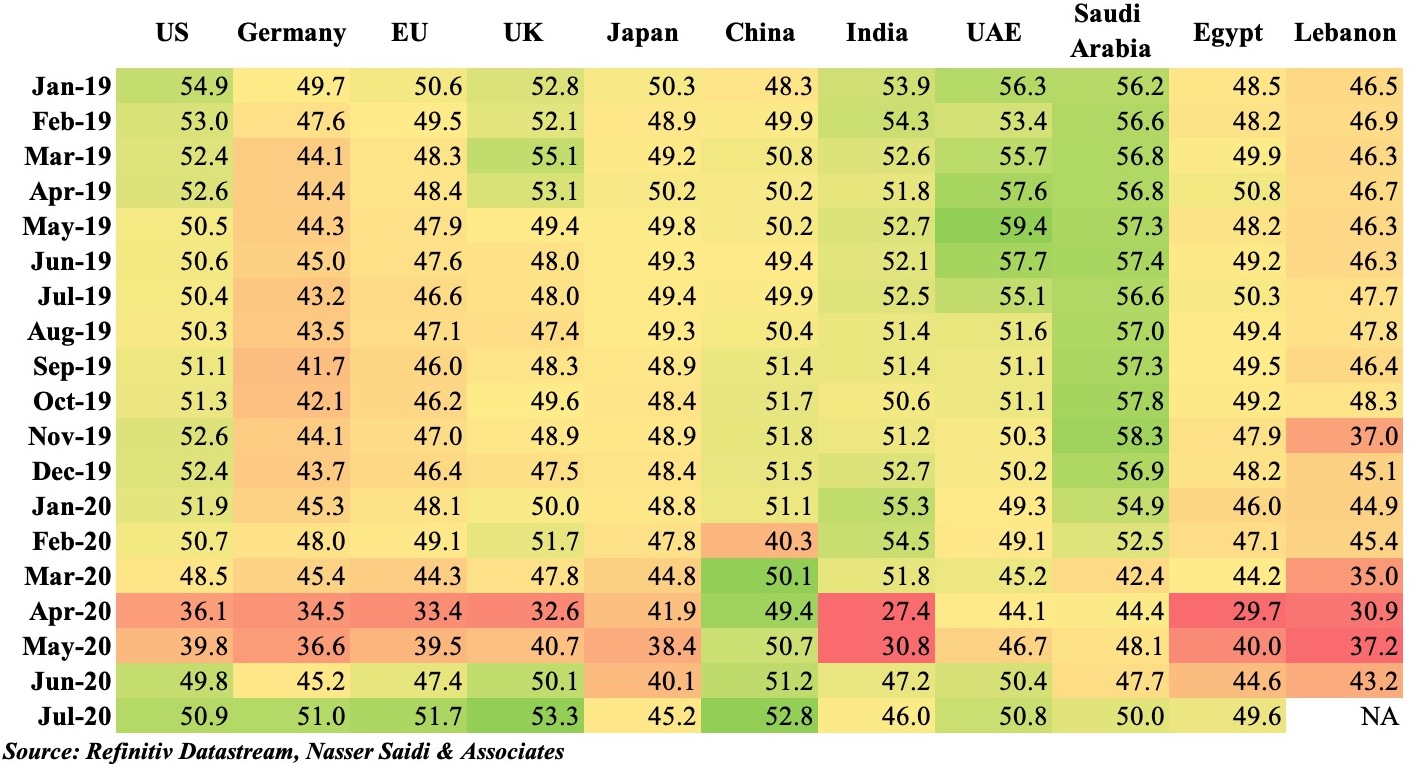

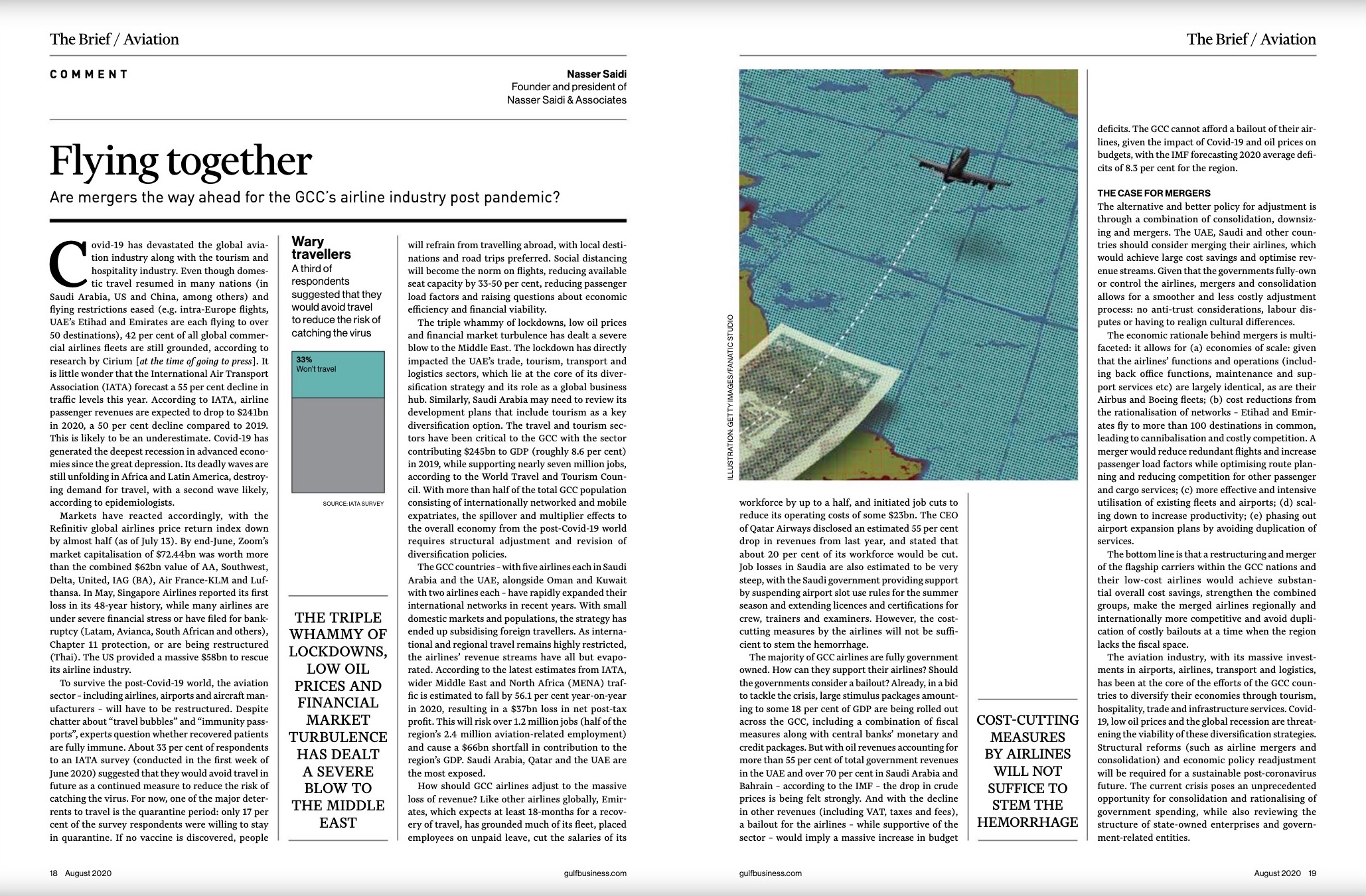

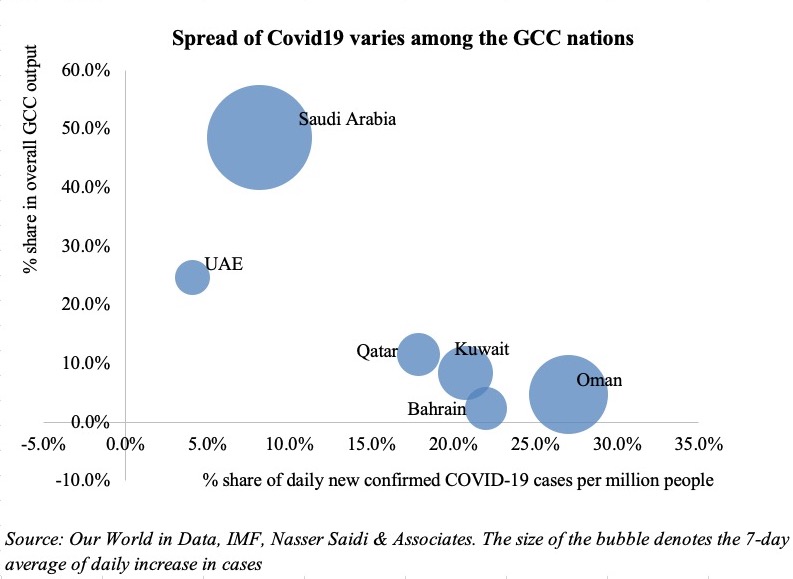

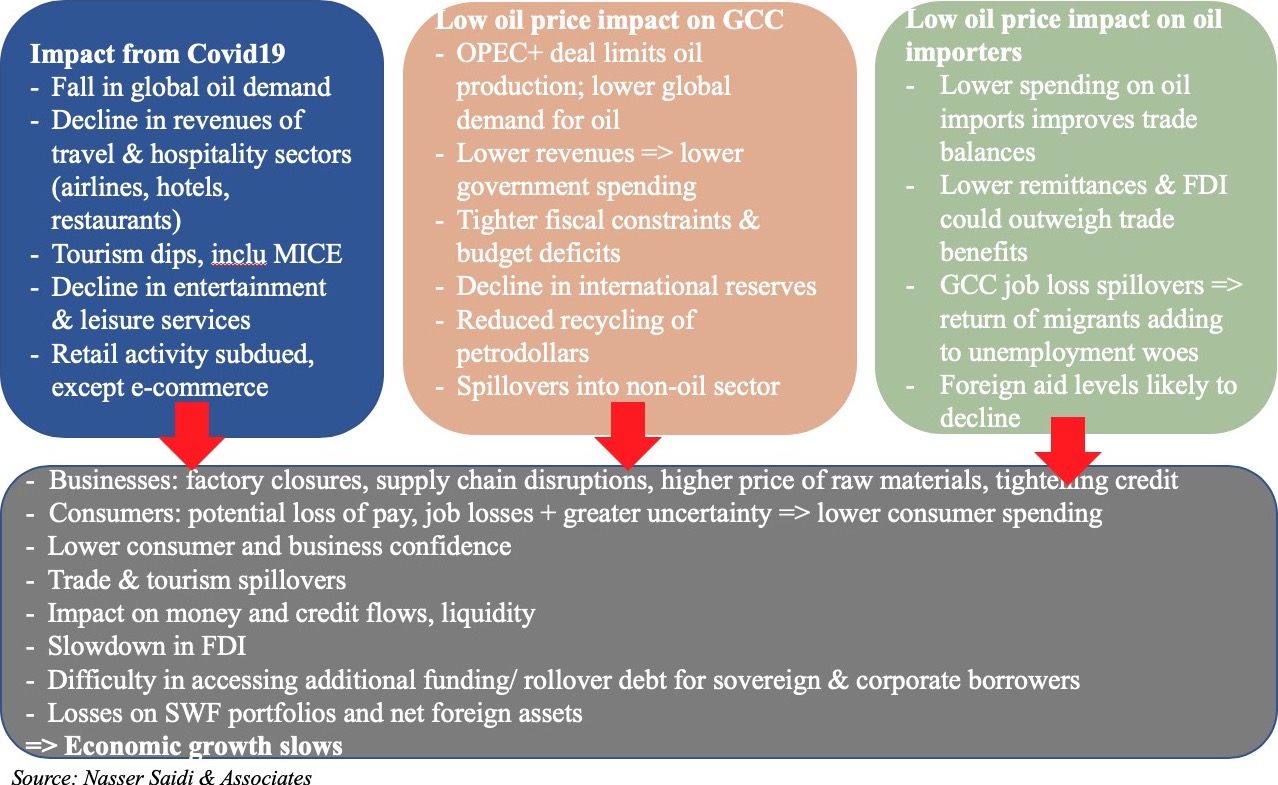

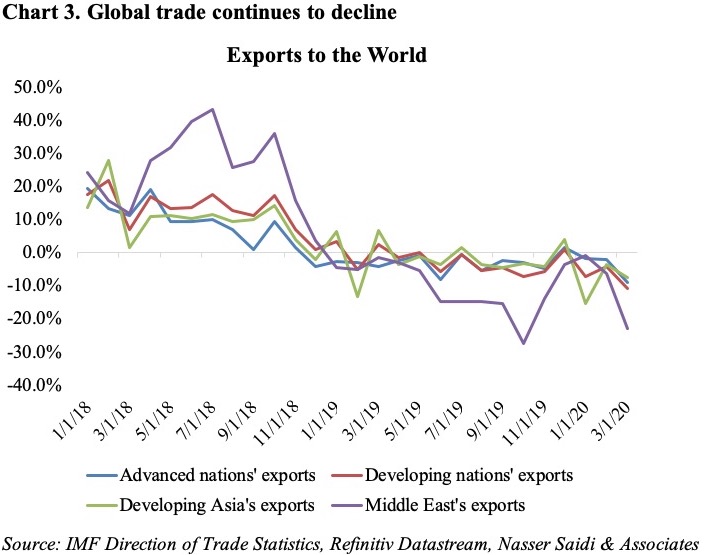

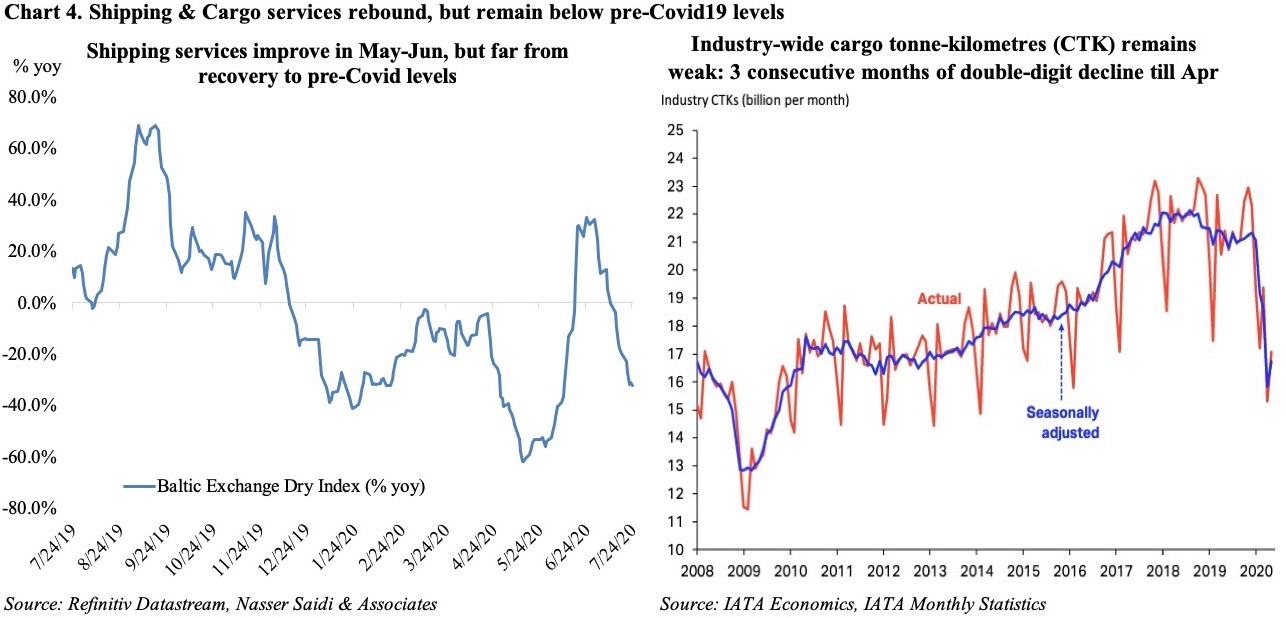

Middle Eastern and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) economies are heading toward a recession in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, collapsing oil prices, and the unfolding global financial crisis.