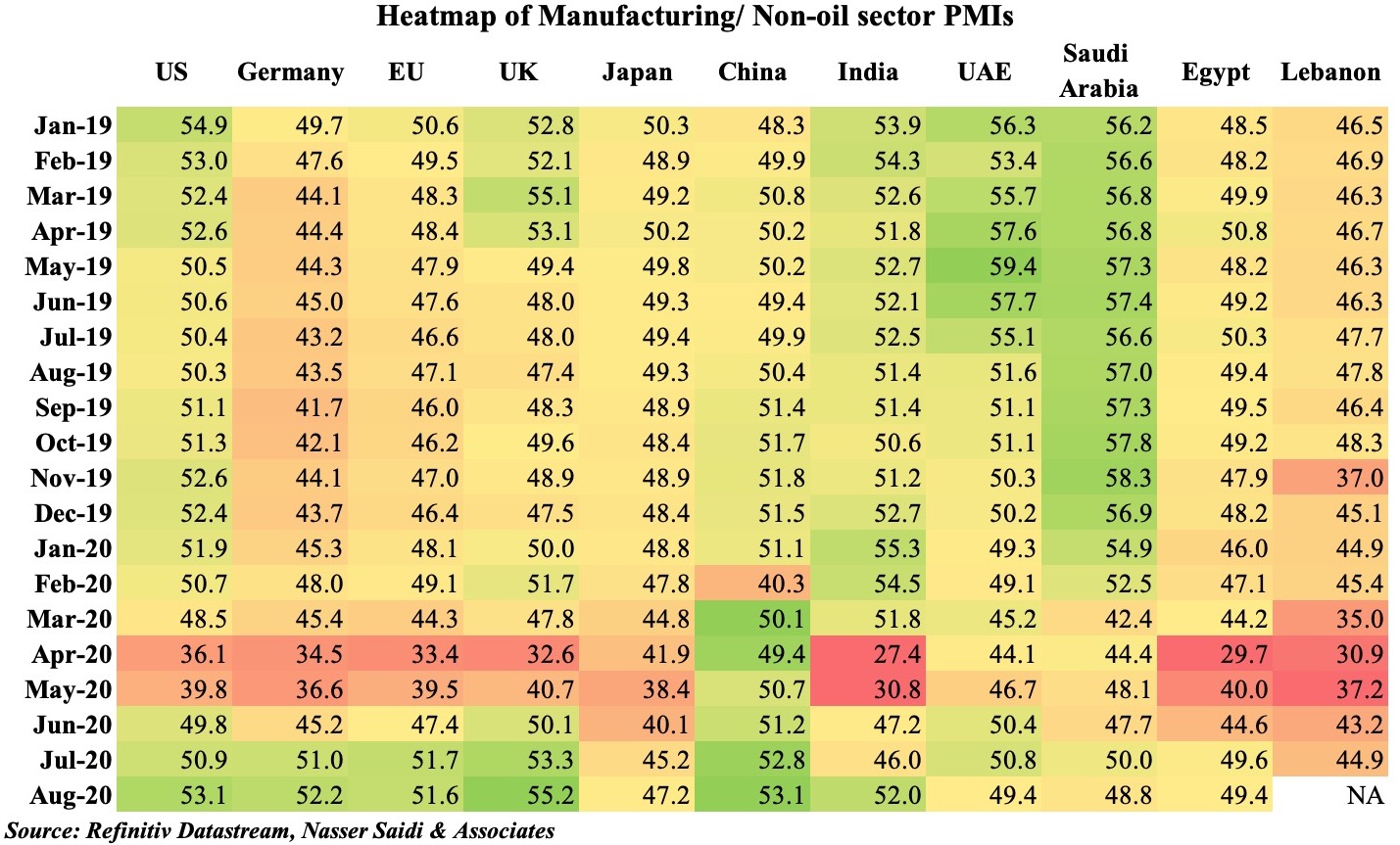

Charts of the Week: As manufacturing PMIs touch new highs in Aug, services PMI stalls. Regional activity is at odds with global peers. Are consumers/ businesses feeling the pinch of Saudi Arabia’s VAT hike? Why is the credit disbursement pattern different in the UAE?

1. Manufacturing PMIs: Global vs. Regional

Manufacturing PMI numbers for August signal a tentative recovery compared to the massive dip in the Covid19 lockdown period. Global manufacturing PMI reached its highest in 21 months (51.8 from Jul’s 50.6), as output and new orders rose at the fastest rates since Apr and Jun respectively, while export demand stabilised. The headline manufacturing indices in the US and Europe improved as restrictions were lifted and more production came online. However, a key point to note is that in many cases export demand has not recovered as much as domestic demand (post lockdown). Meanwhile, services sector activity has almost stalled: the initial rebound is tapering off given ongoing social restriction policies. The bottom line is that though PMIs have shown some improvement, the impact might be hampered by rising unemployment, subdued international demand alongside overall economic and public health uncertainty.

From the list above, only Japan and countries from the Middle East are sub-50 indicating a contraction. Egypt posted the 13th straight month of contraction in Aug, while both Saudi Arabia and UAE moved below 50. The relevant question for the region is why? A sharp decline in jobs is the main drag on headline indices, as firms try to lower operational costs amid a scenario of weak demand and subdued growth prospects. In the UAE, not only did the employment sub-index fall to its lowest in 11 years (with one in 5 panelists reducing number of employees) but firms also had to deal with price discounting to remain competitive. In Saudi Arabia, the hike in VAT (from Jul) drove up input costs, adding more pressure on firms. Overall, a prolonged weaker recovery could lead to firm closures, that would lead to job losses, bankruptcies as well as an impact on the banking sector via an increase in NPLs.

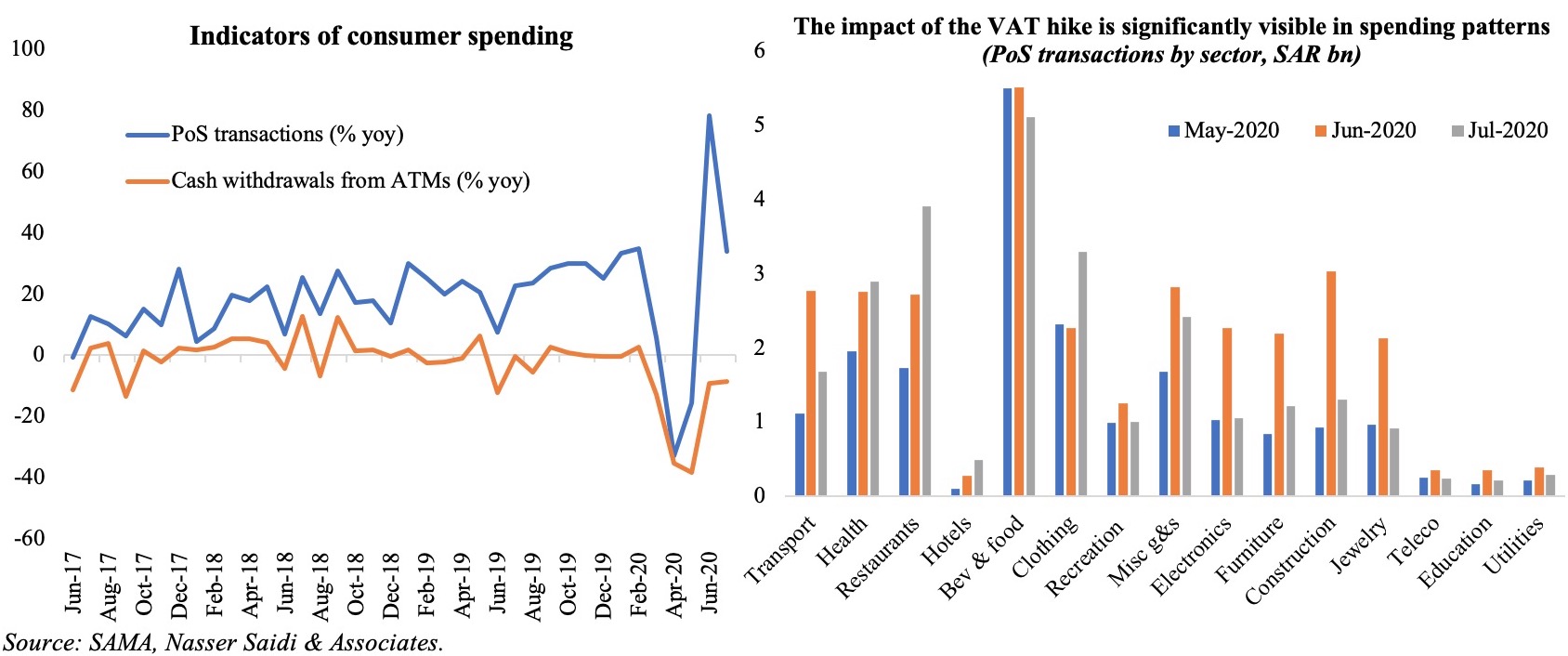

2. Saudi Arabia impacted by the VAT hike: how has consumer spending fared?

Saudi Arabia’s VAT hike has negatively affected consumers as well as businesses. Consumers, who ratcheted up spending in June (similar to patterns in Dec 2017, prior to the introduction of VAT in Jan 2018), have reverted to “normal” spending habits come July. Comparing the patterns by sector, the difference in Jul is striking in purchases of big-ticket items – electronics, furniture, jewelry as well as construction and building materials. Interestingly, sectors like hotels, restaurants and clothing showed an uptick in spending in spite of the VAT hike – a probable explanation is end of lockdown and the Eid-al-Adha holidays which fell towards end of the month; new clothes are a must and restrictions on international travel resulted in people opting for more regional travel and staycations, thereby boosting payments at hotels and restaurants.

3. Is private sector activity supported by credit disbursement? A tale of two nations

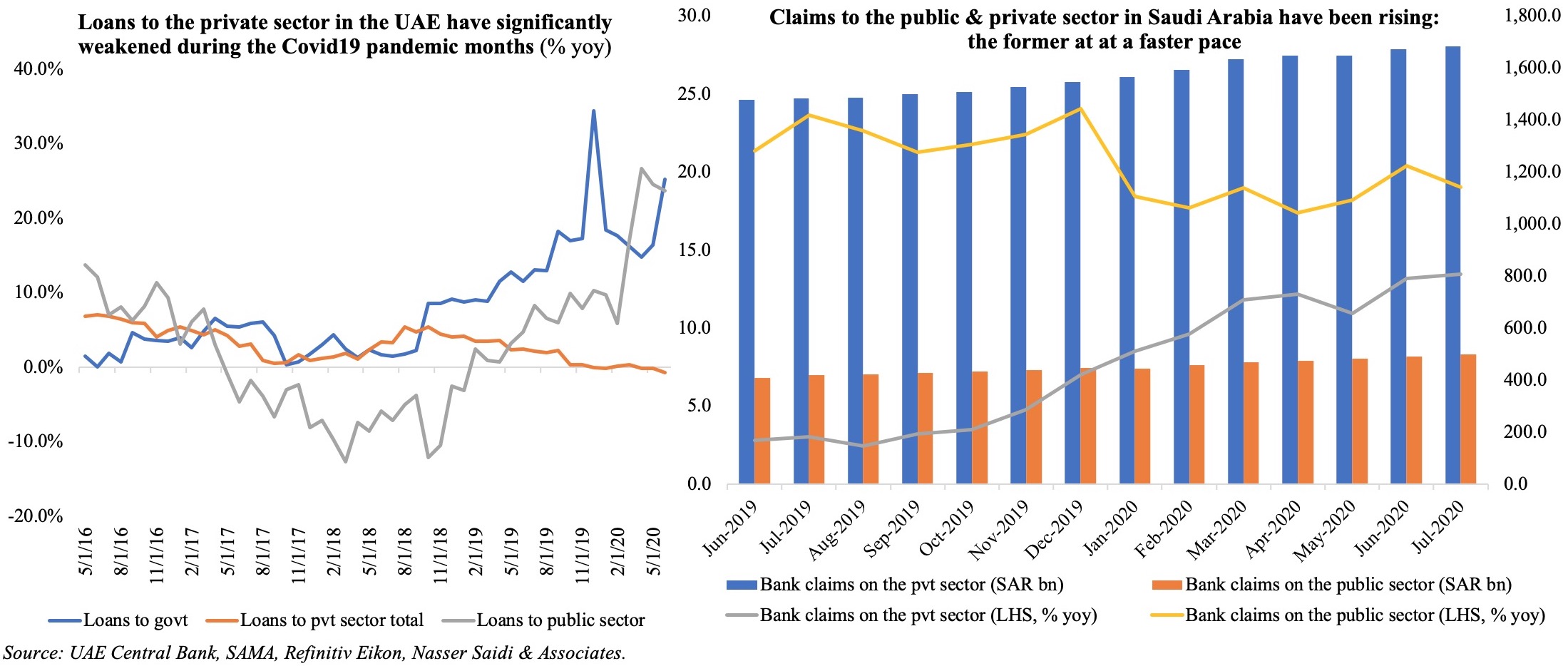

Both the Saudi and UAE central banks have undertaken multiple measures to support their economies through this Covid19 phase: this includes increased liquidity, deferral of loan payments (which was recently extended further till Dec 2020 by SAMA) as well as support for the private sector (specifically those businesses most affected by the pandemic, and SMEs) from banks. However, while credit to the private sector has picked up in Saudi Arabia, the opposite was the case in the UAE. Why?

4. The big picture of credit activity in the UAE

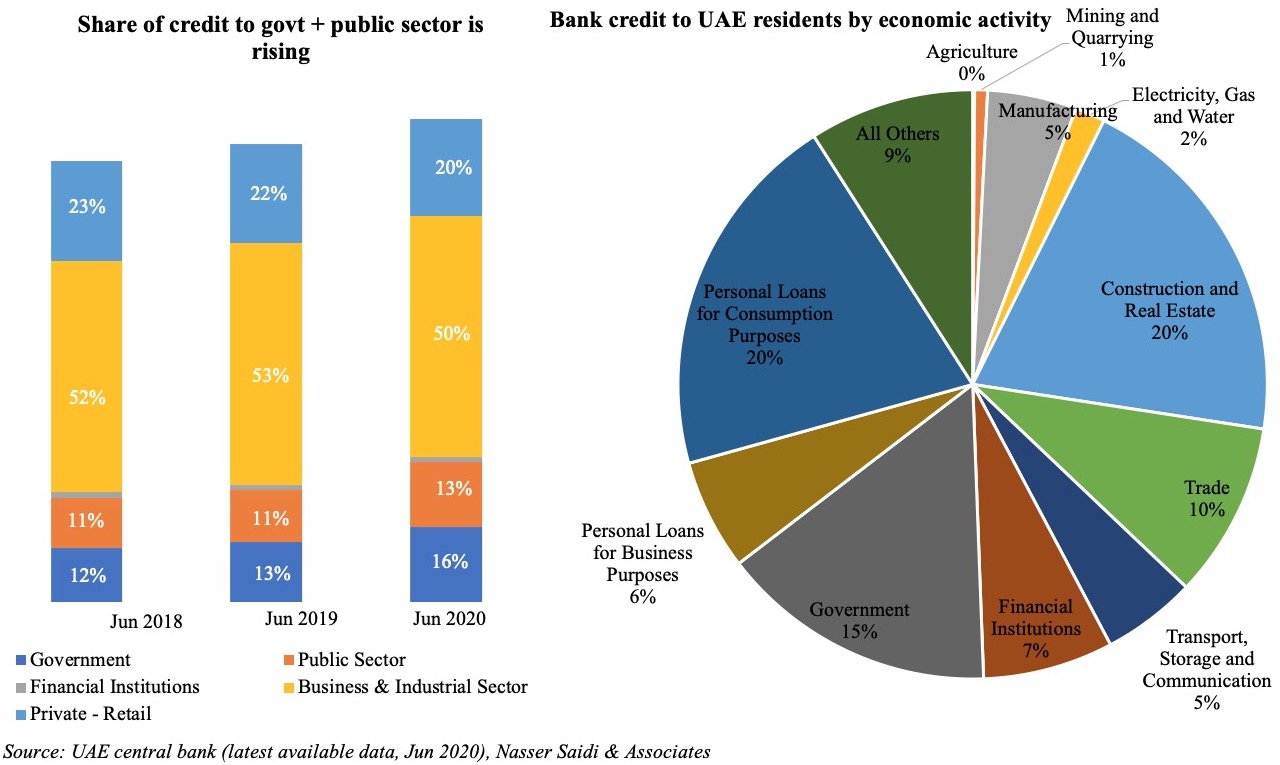

On close inspection, lending to the private sector in the UAE has been on the decline since Aug 2018 and worsened during the pandemic phase (Fig 3). In both year-on-year and month-on-month terms, growth in credit to the public sector and government constantly outpaced the private sector, leading to a growing share of the public sector and government. UAE banks lent most to the business sector (50% of total, as of Jun 2020 vs. 53% in Jun 2019), while the public sector & government together account for close to 30% of all loans (vs. 24% a year ago). Lending remains quite high for construction/ real estate (20%), government (15%) and personal loans (20%); this compares to 21.8%, 12.9% and 21.2% respectively a year ago.

The UAE central bank has been proactive in releasing liquidity to the financial sector during Covid: in addition to the Targeted Economic Support Scheme (Tess) rolled out in Mar, in early-Aug it temporarily relaxed the net stable funding ratio (NSFR) and the advances-to-stable resources ratio (ASRR) by 10 percentage points to enhance banks’ capacity to support customers. As of July 18, banks had withdrawn AED 43.6bn, equivalent to 87.2%, of the AED 50bn Tess programme made available to them. The central bank also disclosed that, as of Jul 2020, 260k individuals and 9527 SMEs had availed the interest-free loans under Tess; credit to SMEs accounted for 9.3% of total amount disbursed to the private sector and individuals had received support worth AED 3.2bn from banks. This is but a drop in the ocean compared to the overall amount made available to the banks (i.e. AED 50bn Tess, part of the wider AED 100bn stimulus unveiled in Mar, and a further easing of buffers raising stimulus size to AED 256bn).

In this context, the questions to be answered are two-fold: 1. Are customers not seeking loans during these troubled times? Or 2. Are banks unwilling to lend during these troubled times? The answer is not crystal-clear, but more likely a combination of both (as evidenced below).

According to the latest “Credit Sentiment Survey” by the UAE central bank, about 53% of respondents stated that the demand for both business and personal loans in Q2 had declined either substantially or moderately. In the backdrop of Covid19, and heightened economic uncertainty, it is likely that consumers do not want to take on loans they cannot service or repay in case of job loss or firm closures; the same applies for businesses in sectors that are tourism-specific or aviation/travel-related firms or others affected by the pandemic (insolvencies/ bankruptcies). On the other hand, for banks, knowingly lending to such firms/ customers could result in an increase in NPLs that would affect their profit margins and bottom line: going by the H1 earnings of the 4 largest listed banks in the UAE, combined net profits are down by 36% yoy while provisions have increased (ENBD by 243% yoy). So, banks have tightened credit standards instead, hence lowering pace of lending to the private sector. Both demand side and supply side of credit are impacting credit.