The article titled “Lebanon at a Turning Point” appeared in Al Arabiya on 23rd January, 2020 and is posted below. Click here to access the original article.

Lebanon at a Turning Point

Endemic and persistent corruption, mismanagement, gross mal-governance, and failure to address Lebanon’s economic, social, and environmental challenges have driven protestors to throng the streets amidst bank closures, payment restrictions, and foreign exchange controls. Protesters had called for a cabinet of professionals, “technocrats,” politically independent, experienced persons, divorced from sectarian politics. The new government formed under duress is a mix of professionals and politically affiliated members. Significantly, it is comprised of 20 non-parliamentarians promising better accountability and has six female members (including the Middle East’s first female defense minister). However, the stark reality, as Prime Minister Hassan Diab clearly identified, is that the country is at a “financial, economic, and social dead end.” Indeed, Lebanon has become a failed state. Will the new government have the political courage to undertake deep and unpopular reforms? Will it be willing to commit political suicide?

The new government has a gargantuan task ahead: It must immediately address the interlinked economic, banking and financial, and currency crises, not to mention a deadly environmental crisis. The accumulated difficulties have ballooned over the past three months due to a series of policy mistakes and inaction including the panic-inducing closure of the banks, informal capital controls, restrictions on domestic and external payments, a rapid depreciation of over 40 percent of the Lebanese pound in the parallel market and effective inconvertibility of deposits. In turn, the pound’s depreciation and the liquidity crunch have led to a sharp acceleration of inflation (some 30 percent), a sharp drop in economic activity (e.g. car registrations dropped by 79 percent year-on-year in November), leading to growing layoffs and unemployment, business closures/bankruptcies, and falling incomes, resulting in a collapse of investment, a sharp curtailment of household consumption, and more than a 50 percent fall in government revenue. The forecast is that real gross domestic product could decline by 10 percent, a great depression, not a recession.

Time is running out for Lebanon. Sovereign debt has risen to 160 percent of GDP, with a projected debt service of $10 billion, equivalent to 22 percent of GDP and over 60 percent of government revenue. The fiscal deficit jumped to about 15 percent of GDP last year (from a budgeted 7.5 percent) and is likely to rise again this year. The debt dynamics and fiscal deficit are on an unsustainable path, with central bank monetary financing of the deficit heralding rapidly increasing inflation and accompanying depreciation of the Lebanese pound. Lebanon’s external accounts are also in crisis, with the current account deficit (some 26 percent of GDP), aggravated by falling remittances and a surge in capital outflows, despite the illegal and unofficial capital controls.

What should the policy imperatives be of the new government? Fundamentally, the Diab government needs to develop and implement a series of economic and structural reforms that aim to restore trust in the government and its institutions, notably through an anti-corruption strategy and stolen assets recovery program, and addressing the fiscal, banking, financial, monetary, and currency crises to avoid a lost decade of economic depression, poverty, deep social unrest, and political chaos. The immediate priorities include the following reforms.

Establish an emergency cabinet committee for immediately implementing economic and financial policy reform measures.

An economic recovery and liquidity reform program is required and must be prepared and agreed upon with the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Lebanon needs a multilaterally funded package of some $20-25 billion for economic and social stabilization, budgetary and balance of payments support, and a redesigned CEDRE program. In 2018, more than $11 billion was pledged in soft loans at the CEDRE conference in Paris, funding from which being unlocked is dependent on reforms made in the country. Prime Minister Diab’s announcement of potential visits to Saudi Arabia and other Gulf nations would be a propitious opportunity to discuss participation in the reform program.

A credible fiscal reform should top the list of policy priorities.

Starting with the 2020 budget, the aim should be to achieve a 5-6 percent primary budget surplus over the next two years through expenditure and revenue measures. These would include the removal of subsidies on electricity and fuel, which are major drains on the budget, revisiting public sector salaries and pensions, in addition to public procurement laws and procedures, and improved tax compliance. But medium- and long-term fiscal sustainability requires imposing permanent constraints on fiscal policy through two fiscal rules: a budget balance rule (e.g. budget deficits not to exceed 2 percent of GDP) and a debt rule (e.g. debt-to-GDP should not exceed 80 percent of GDP).

Public debt restructuring is key.

Given the Eurobond maturing in March 2020, another initial pain point is initiating negotiations on restructuring and re-profiling Lebanon’s public debt, including the debt of Lebanon’s central bank. So far, the absence of an empowered government haa constrained any negotiations on restructuring its debt. Lebanon’s crisis-hit bonds have been flashing warning signs of a sovereign debt distress if not default ahead. Yields on the government’s $1.2 billion of notes maturing in March were close to 200 percent on January 22 (versus at 13 percent just before the start of protests), while the price of other Lebanese Eurobonds plummeted to historic lows. The new government should immediately initiate debt restructuring negotiations within the comprehensive economic stabilization and liquidity program. A successful restructuring could reduce the net present value of debt by some 50 percent, substantially lowering the debt burden and its servicing.

The banking sector must be restructured.

Given that 70 percent of Lebanese banks’ assets are invested in sovereign debt and central bank paper, a restructuring of public debt will necessitate an extensive reform of the banking system, including a bail-in of the banks through a $20-25 billion recapitalization by existing and new shareholders, a capitalization of reserves, a sale of assets, – such as real estate, investments, and foreign subsidiaries – and a consolidation of banks to downsize the sector.

Lebanon needs to change its monetary policy and move to a managed flexible exchange rate regime.

The high interest rates required to maintain the overvalued official dollar peg generated structural current account deficits, created a domestic liquidity squeeze, crowded out the private sector, and increased the cost of public borrowing. Reform starts with admitting the failure of the pegged regime, recognizing the de facto depreciated parallel market rate, and instituting formal capital controls through legislation during the economic transition period.

A social safety net must be implemented to protect the vulnerable.

Importantly, given the need for painful reform measures and rising extreme poverty levels, a targeted and well-funded social safety net, to the tune of some $800 million, needs to be put in place to protect the poor and vulnerable.

This is a historical turning point. Either Lebanon will choose a path that leads to the economy’s stabilization and a gradual recovery over a three- to five-year transition period, or it will avoid necessary reforms, confirming the country as a failed nation and dooming it to a decade of desolation.

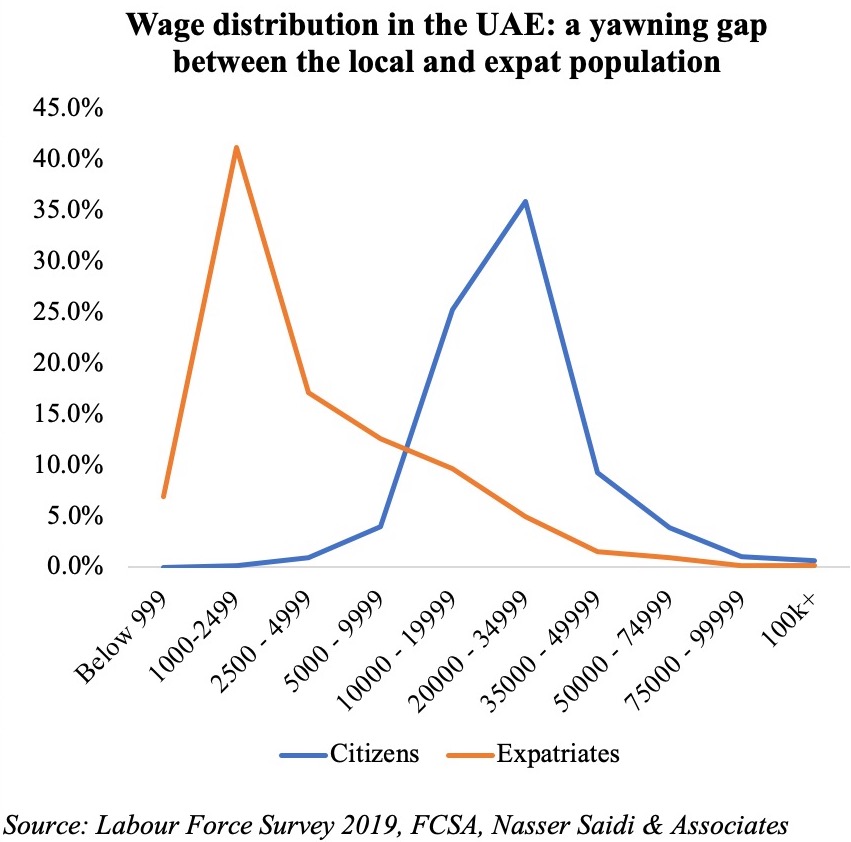

The Survey also confirms the disparity in wages between local and expat population: more than one-third of Emirati respondents disclosed receiving monthly wages between AED 20-35k (versus just 5% of expats in the same income bracket). This brings to the forefront two issues:

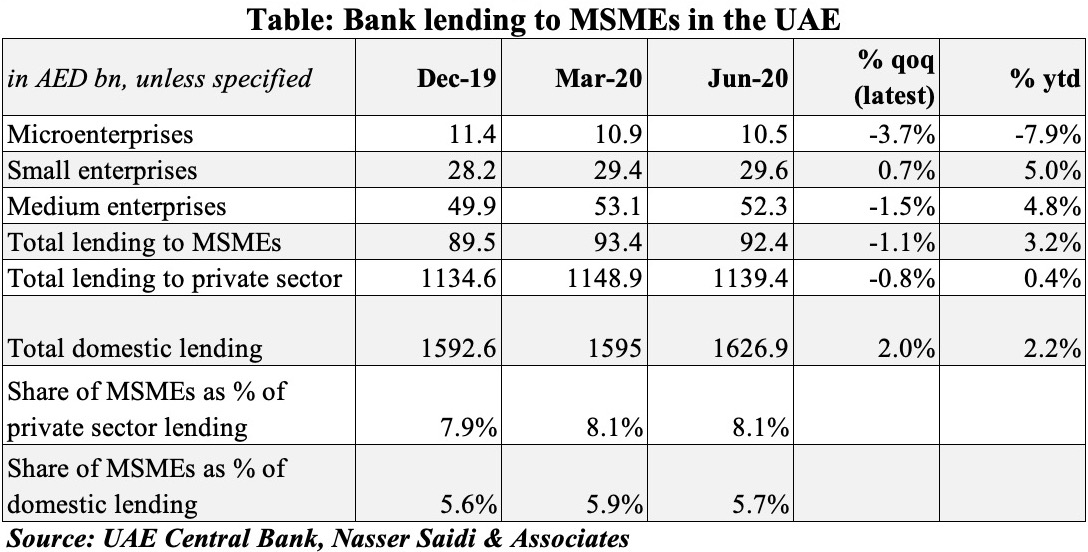

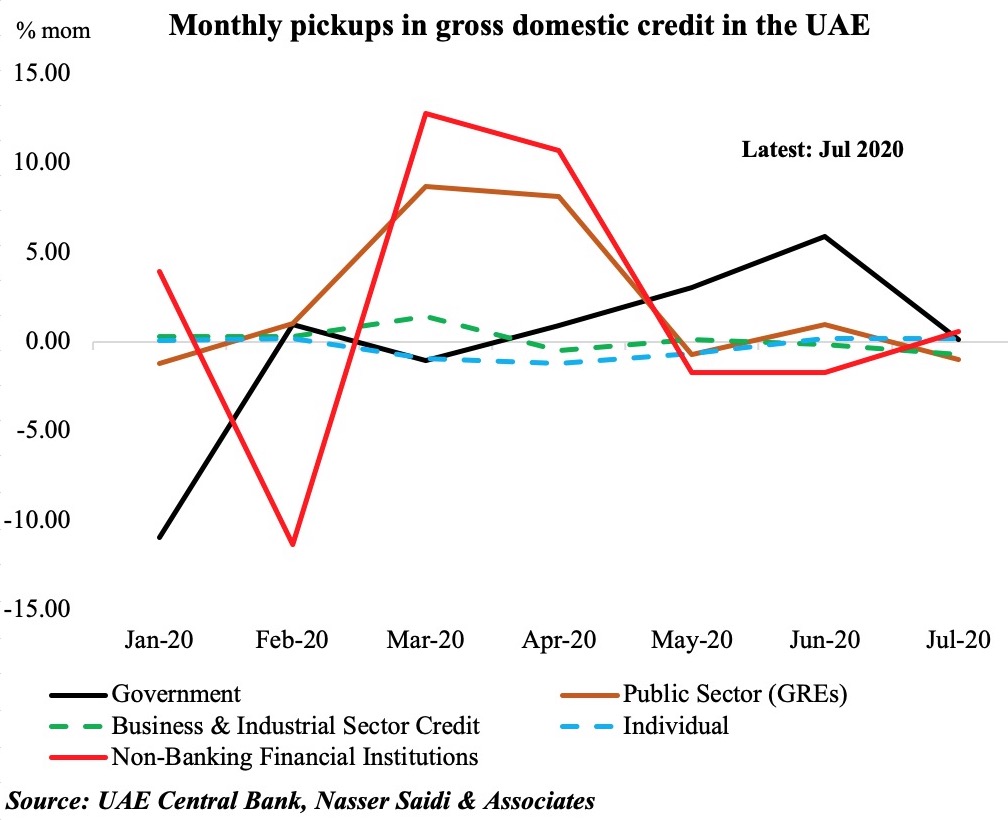

The Survey also confirms the disparity in wages between local and expat population: more than one-third of Emirati respondents disclosed receiving monthly wages between AED 20-35k (versus just 5% of expats in the same income bracket). This brings to the forefront two issues: ral bank shed some light on the broader credit movements: the accompanying chart shows the monthly changes in gross domestic credit. The dotted lines are credit to businesses and individuals (the private sector) which show no substantial increases – in fact, it increased by an average 0.9% year-to-date (ytd) for businesses and dropped by 2.1% ytd for individuals. The uptick in lending to the public sector (government related entities) and government have been discussed previously

ral bank shed some light on the broader credit movements: the accompanying chart shows the monthly changes in gross domestic credit. The dotted lines are credit to businesses and individuals (the private sector) which show no substantial increases – in fact, it increased by an average 0.9% year-to-date (ytd) for businesses and dropped by 2.1% ytd for individuals. The uptick in lending to the public sector (government related entities) and government have been discussed previously