Weekly Insights 18 Feb 2021: The GCC Labour Market & Remittances – A Forward-looking Viewpoint

Download a PDF copy of this week’s insight piece here.

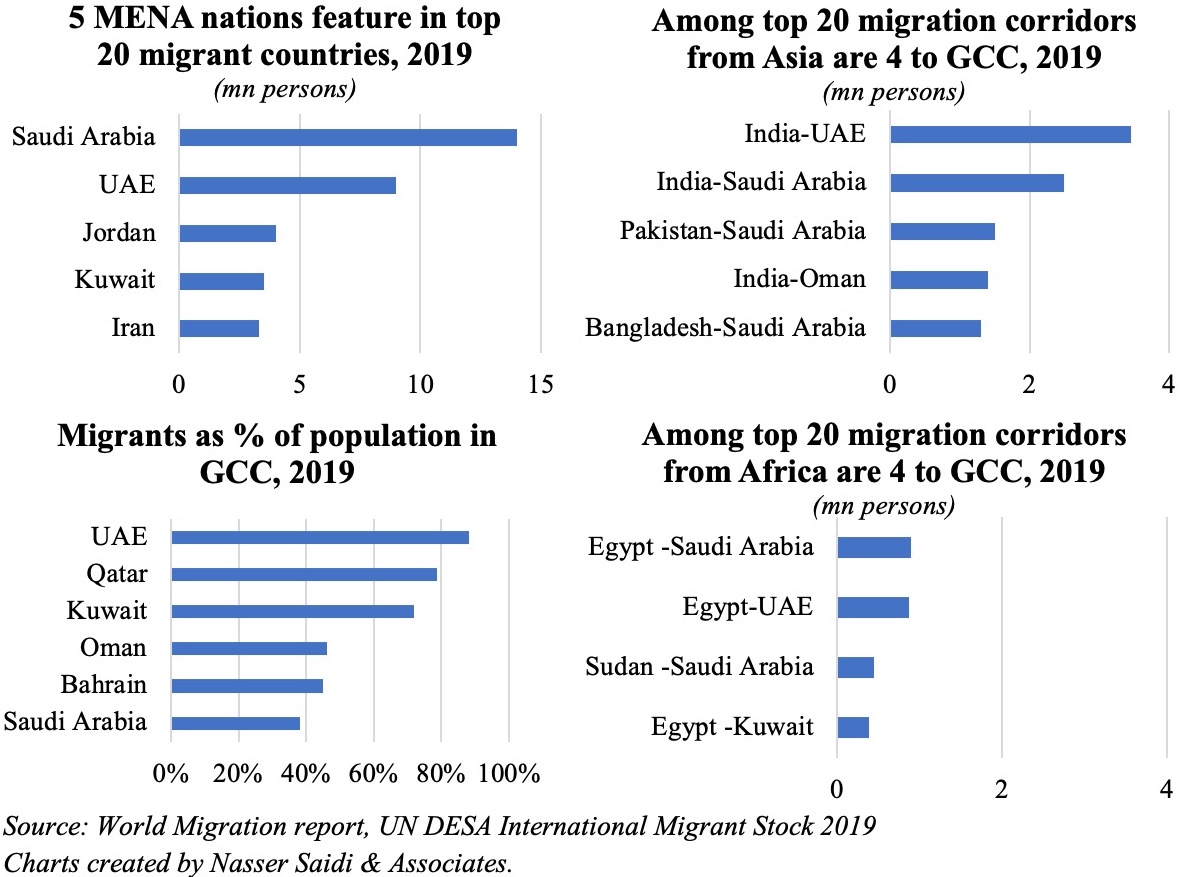

It is no secret that the GCC is home to one of the largest migrant communities globally. Five MENA nations feature in the top 20 migrant attracting nations globally (by number of persons). Expat share in population across the GCC varies from Saudi Arabia’s less than 40% to UAE’s high 88%. According to the UN, top 20 migration corridors from Asia and Africa include those to the GCC nations: in 2019, India-UAE was the second-largest migration corridor in Asia (but, second only to refugee movement from Syria to Turkey), while migration from Egypt to Saudi and UAE occupied the top 5th & 6th spots among African nations.

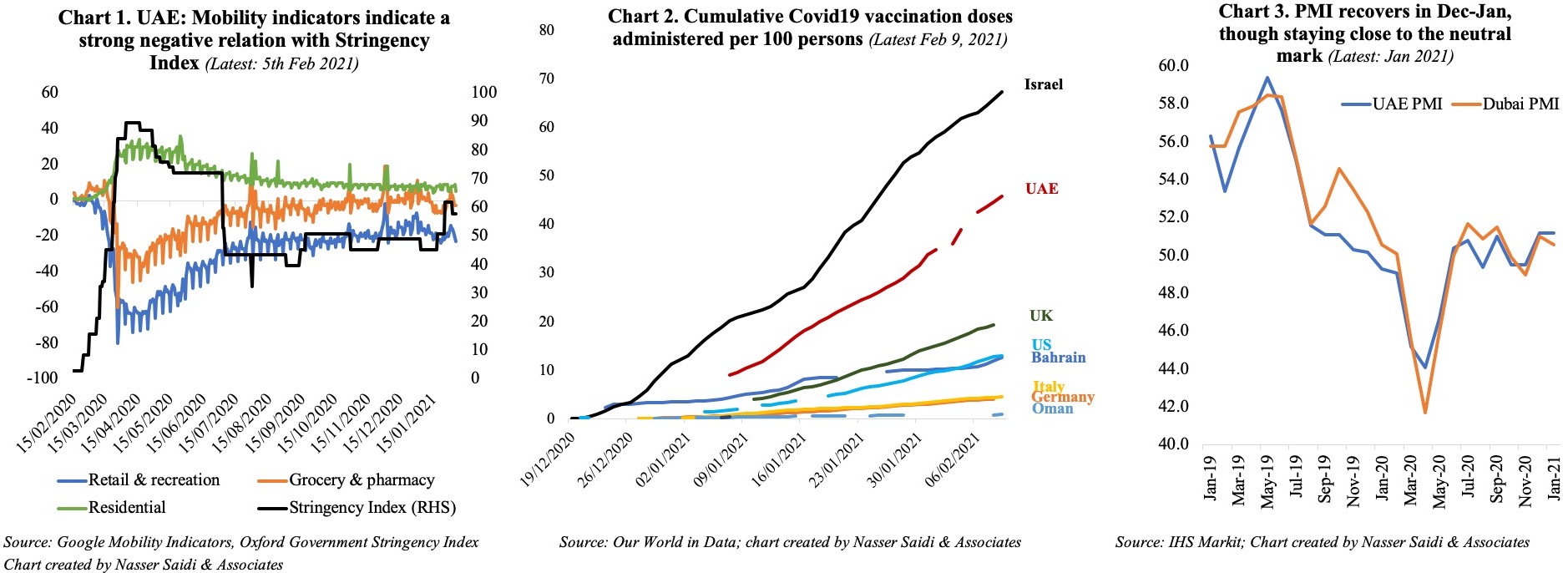

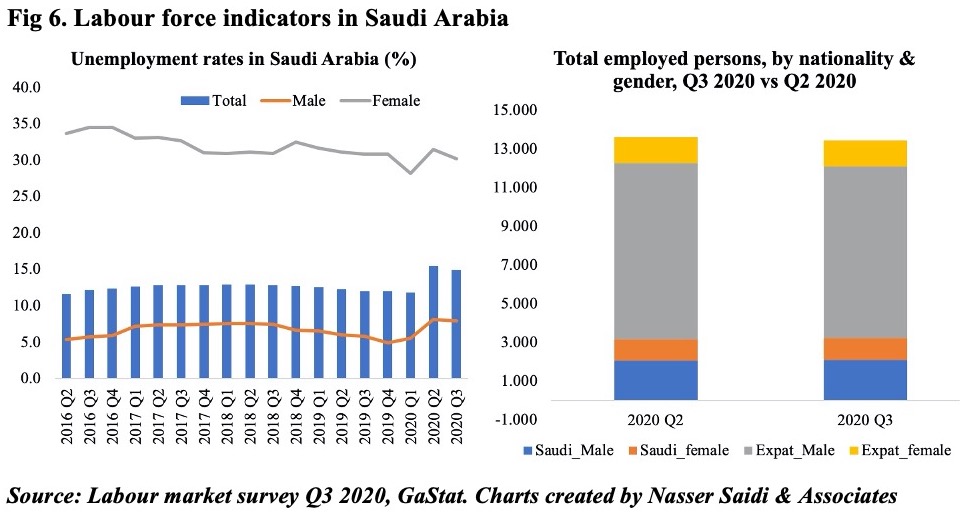

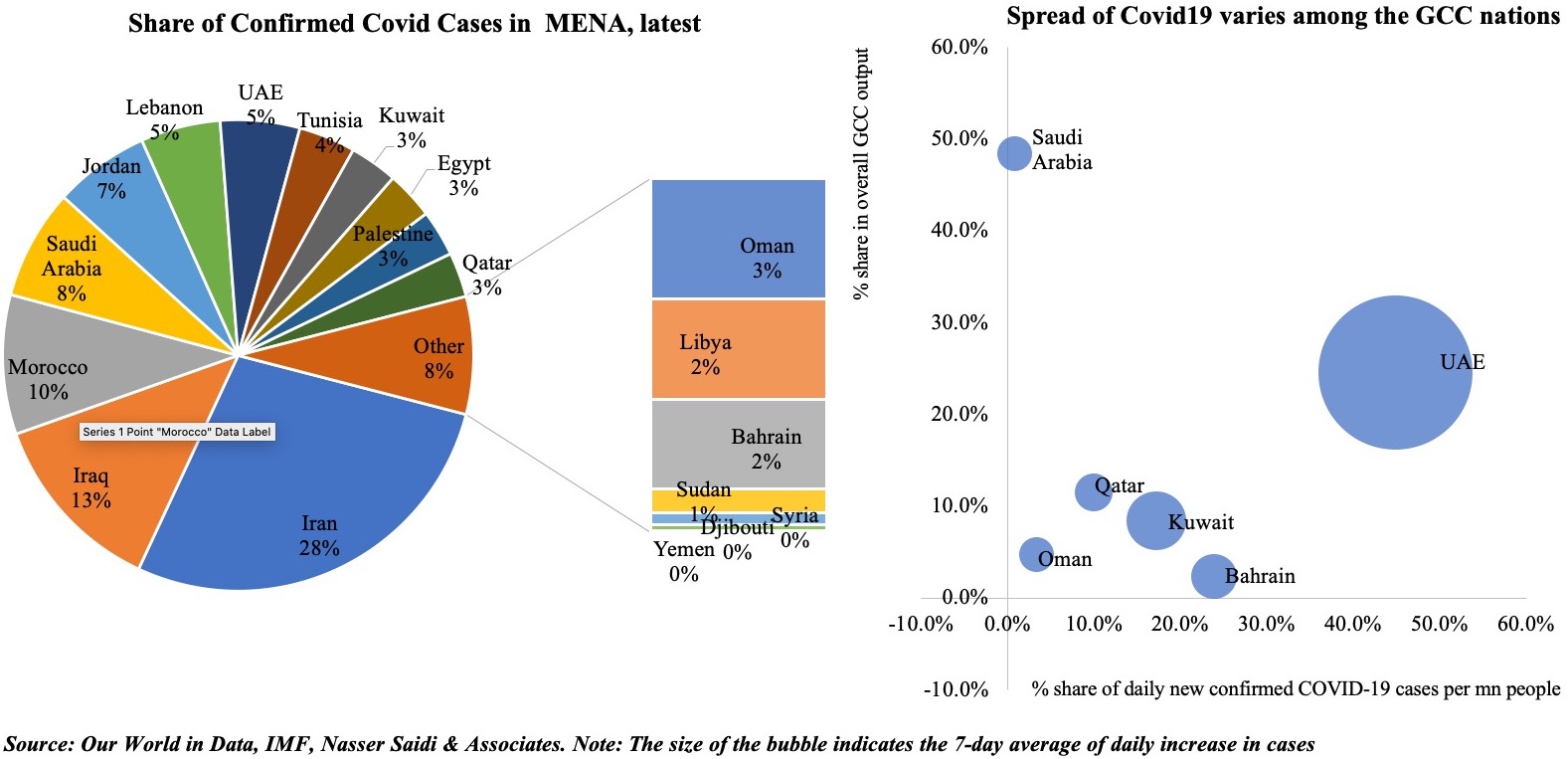

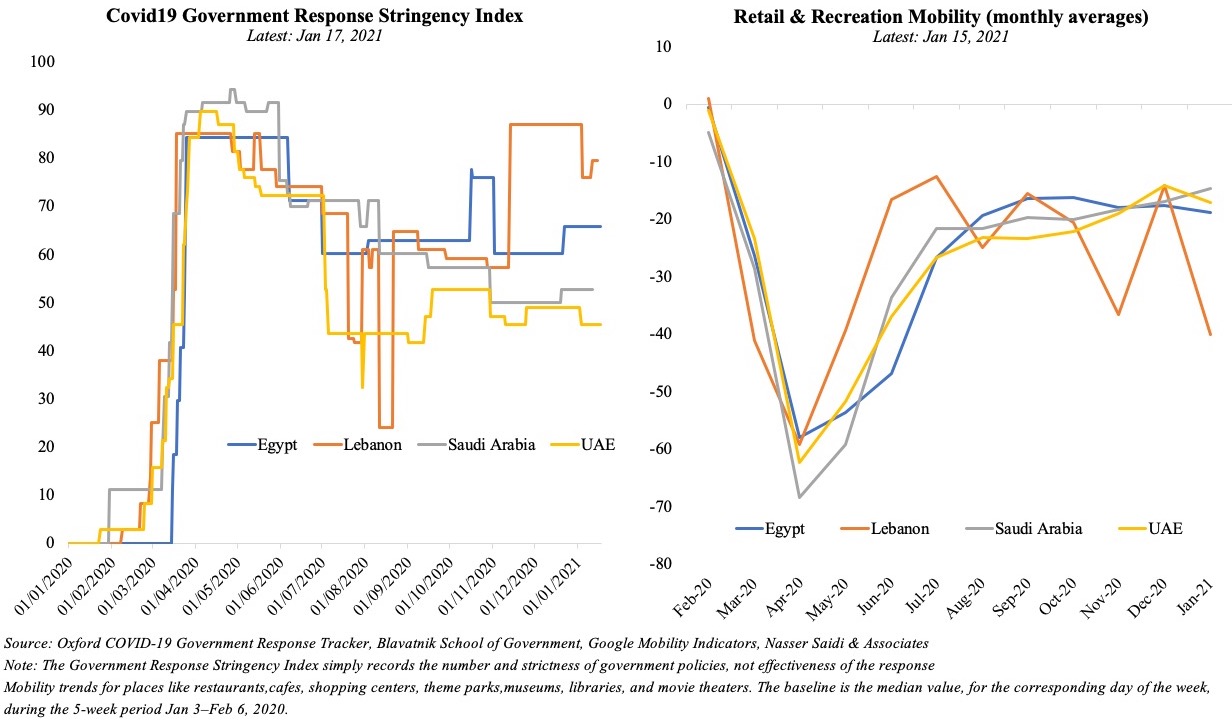

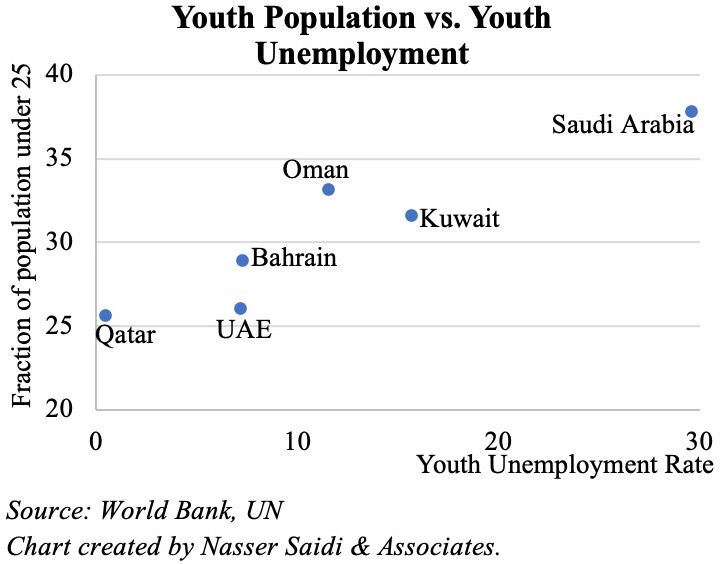

Burdened by Covid19 and lower oil prices last year, job losses in the GCC and return migration has raised key concerns about the sustainability of dependence on expatriate labour. With published monthly data of labour/ employment lacking in most GCC nations, reliance on anecdotal evidence is high. Official NCSI data showed that more than 270k expats left Oman between end-2019 to Nov 2020 (roughly 16%). This Covid19-related “expat exodus” coupled with recent moves to nationalize various professions and replace expats with nationals in senior positions at state-run firms, highlight a growing predicament facing many GCC nations – how does a government justify the need to hire expatriate labour amid rising youth unemployment levels?

This pressure is building up in nations with high shares of population under the age of 25. Depending on labour force participation rates, the IMF estimates that the GCC labour force could grow by an additional 2.5mn nationals by 2025. While similar numbers are more intense in the labour-exporting nations within the MENA region, needless to say that there are some common challenges: job creation (in the private sector), gender disparity, preference to wait for a public sector job, address low levels of efficiency and productivity, to name a few.

- An interesting statistic from the ILO, namely young people not in employment, education or training (NEET) is at a high 16% in the GCC nations (though it pales in comparison with 40% in non-GCC Arab nations) implies that job creation has not been keeping pace with the growth in youth workforce.

- Gender disparities are a commonly acknowledged drawback in the GCC (and wider MENA region). The World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap 2020 report highlighted that it would take the MENA region close to 140 years to achieve gender parity! The Covid19 pandemic throws another spanner in the works with women being more negatively affected on the job front (globally and in the region). Whereas formal education attainment has improved over the years, issues of mobility, cultural norms/ gender roles continue to be significant barriers preventing women from joining the workforce. Even the previously mentioned NEET levels are much higher for women: in 2019, 51.9% of young women in Arab states were classified as NEET vs 17.8% of young men.

- In the GCC nations, labour markets remain segmented: wage premiums in the public sector for lower working hours drives the nationals’ preference for public sector employment. However, the higher wage bills (a strain on government budgets) have not translated into an improvement in the quality of public services (UAE is an outlier) and some standalone studies have highlighted a stagnation in public sector productivity levels.

Remittances in the GCC: should they be taxed?

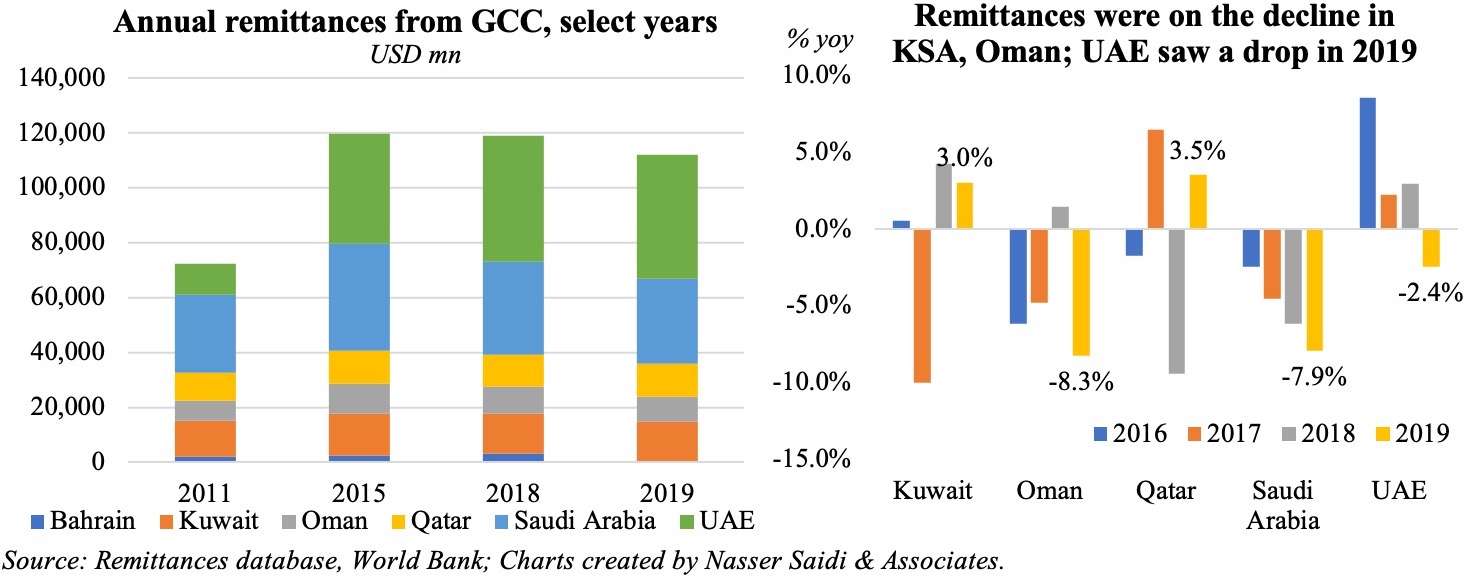

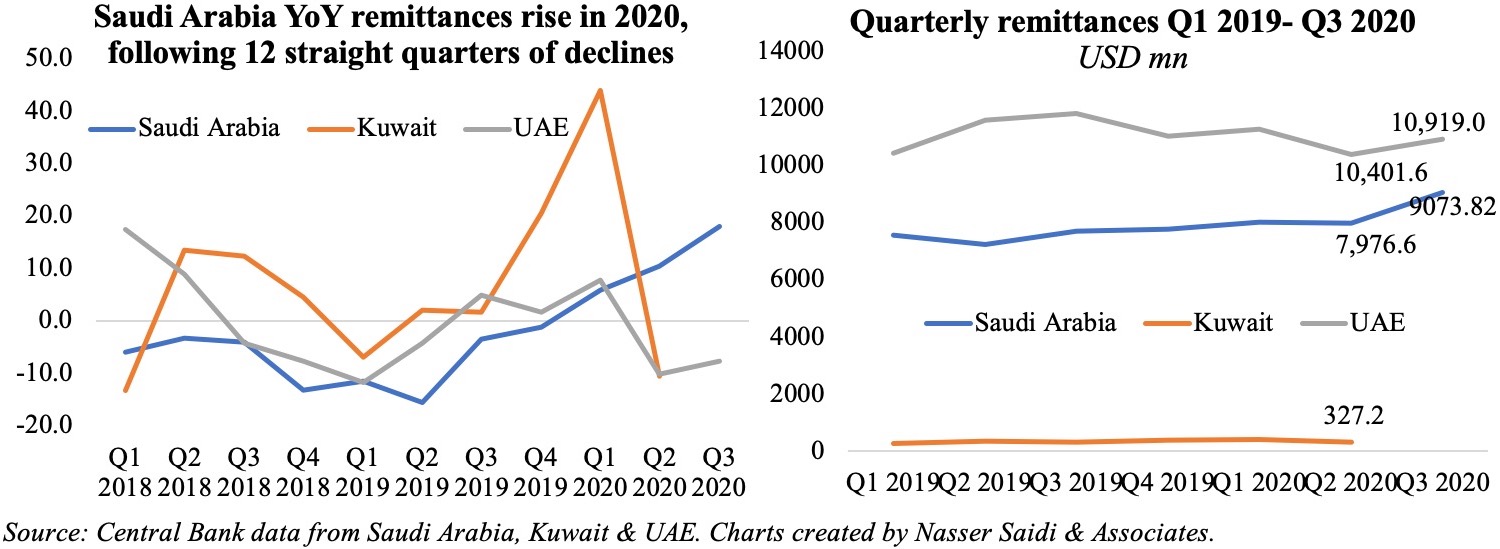

According to the World Bank, outward remittances from the GCC touched USD 112bn in in 2019: while this was a drop of 6% yoy, as a share of GDP it still stood at 11.9% in Oman, 11% in Kuwait and 10.7% in the UAE. Together, UAE and Saudi Arabia account for more than 2/3-rds of total remittances from the GCC. Did the pattern of remittances change during the Covid19 pandemic? The combined effect of the pandemic and related job losses alongside lower oil prices were expected to have an adverse effect on remittances. The World Bank expects global remittances to drop by 7% yoy to USD 666bn in 2020 (and by a further 7.1% in 2021) and inward remittances into the MENA region to decline by 8.5% to USD 55bn in 2020 (and by 7.7% to USD 50bn in 2021) negatively affecting labour exporting countries like Egypt.

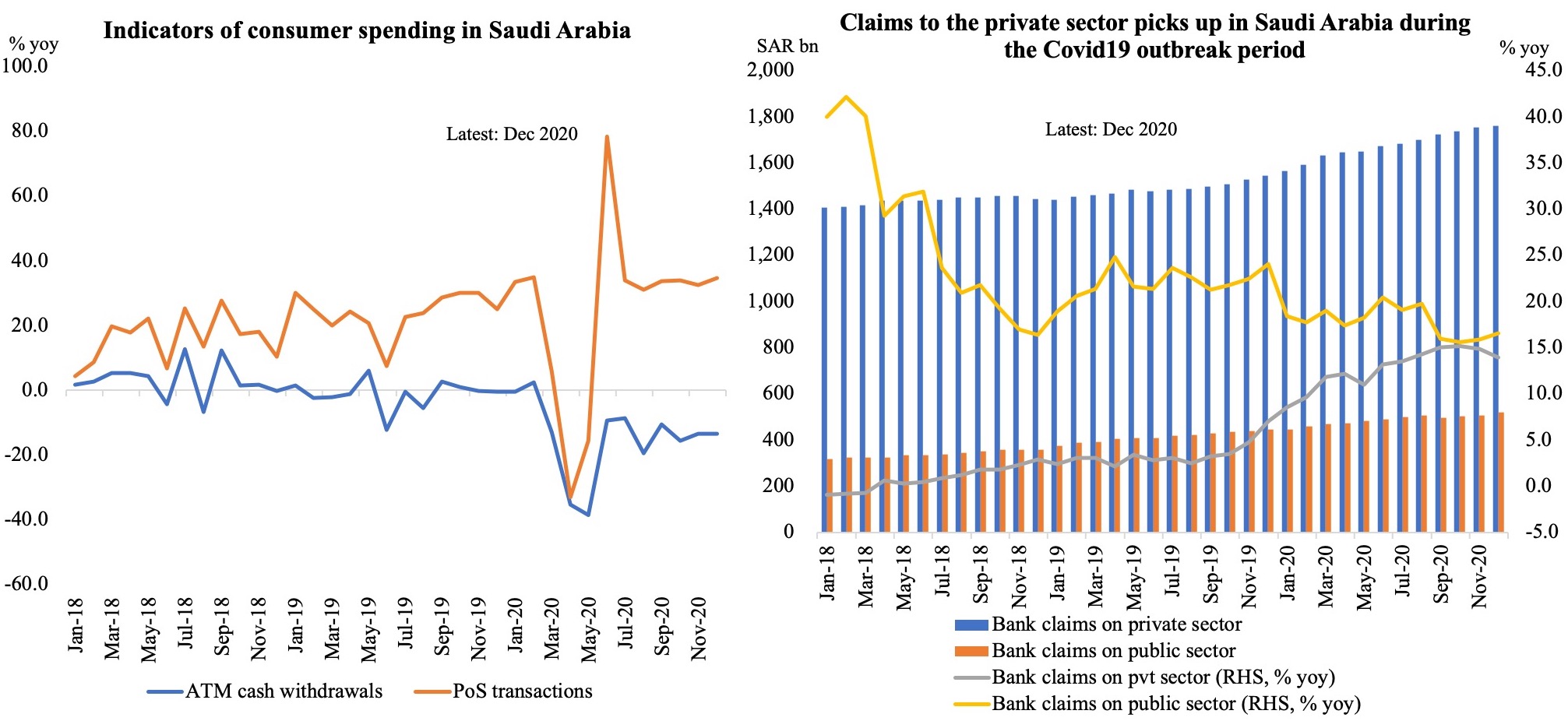

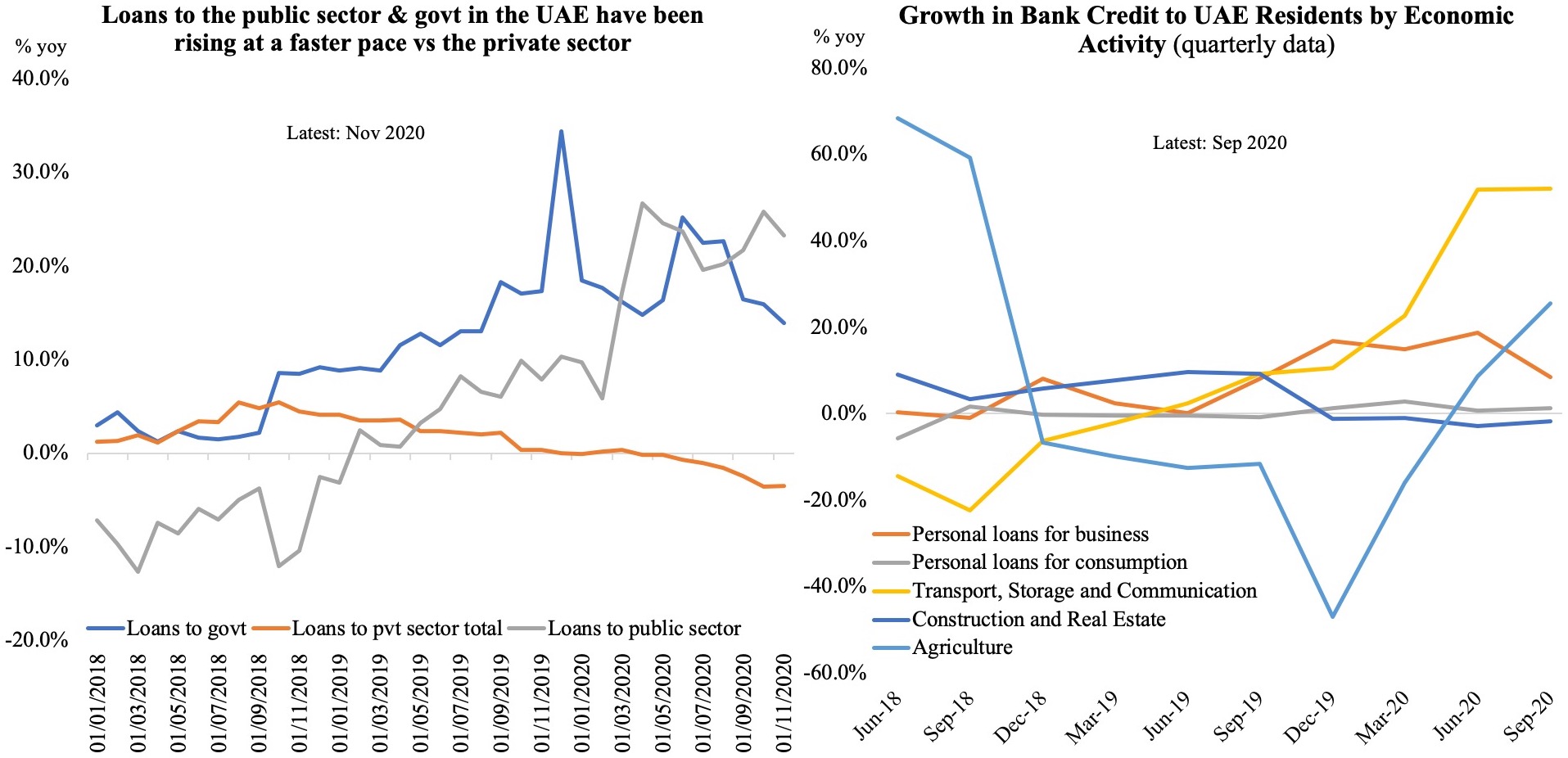

At the GCC level, quarterly (headline) data are available in Saudi Arabia, UAE and Kuwait. Saudi Arabia has witnessed a continued drop in remittance flows consistent with the oil price declines (it saw 12 straight quarters of yoy declines since 2017), alongside the introduction of nationalization policies in many sectors. While the drop in Q2 was consistent across all three nations, both Saudi and UAE reported an increase in remittances in Q3 (Kuwait is yet to release Q3 data). This could be a result of multiple factors: job losses resulting in transfer of savings to the home country, an increase in digital remittances (versus unrecorded cash during trips home), transfer of excess savings (given lack of travel, leisure activities), exchange rate movements and/ or remittances to support families in the home country. The World Bank identified a potential (yet to be evaluated) “Hajj effect” when analyzing remittances into Pakistan and Bangladesh – savings that had been set aside for Hajj were sent home instead given travel restrictions and the reduction in the issuance of Hajj visas.

Should remittances be taxed?

While there have been sporadic calls for a tax on remittances, this has yet to take a credible form and is oft refuted by government/ central bank officials. Oman is currently studying a proposal for a personal income tax on high-earners – if introduced, it will be a first in the region and could see similar rollouts across the region (depending on its impact). Though this will raise a question of “taxation without representation”, there are other approaches to encourage expats to retain their saving and invest in the economies (versus investing in their home country). This essentially boils down to a combination of labour and financial market reforms. Here is a non-exhaustive list.

- Economic diversification into job-creating non-oil sectors (including knowledge-based sectors). This also requires a supportive business environment with the necessary legal framework to ease the cost of doing business as well as additional measures to support SMEs (supporting entrepreneurs)

- Allowing 100% foreign ownership would encourage FDI inflows, create jobs and prompt entrepreneurs and businesses to re-invest into the domestic economy

- Increased labour mobility: a rollout of residency visas versus job-linked visas would encourage expats to stay longer, thereby encouraging investments in the domestic economy (e.g. UAE’s 10-year visas for skilled professionals). Similarly, undertaking pension reforms as well as introducing unemployment insurance schemeswould help retain workers and reduce turnover and training costs.

- Encouragement of investment of domestically mobilized savings in the local economy needs the backing of a deep, broader and more liquid financial market. The introduction of a housing finance/ mortgage market could be one of the ways in addition to facilitating investment in domestic equity/ debt markets.

- Programs for capacity development to resolve skill mismatches via vocational and on-the-job training programs

- Supporting increased participation of female workforce through paid maternity/ paternity leaves and access to childcare facilities. Encouraging women to work increases growth and productivity, not only because women jobseekers typically have higher than average education, but also because this can increase mobility across sectors and jobs and increase household earnings, thereby increasing consumption and investment in housing.

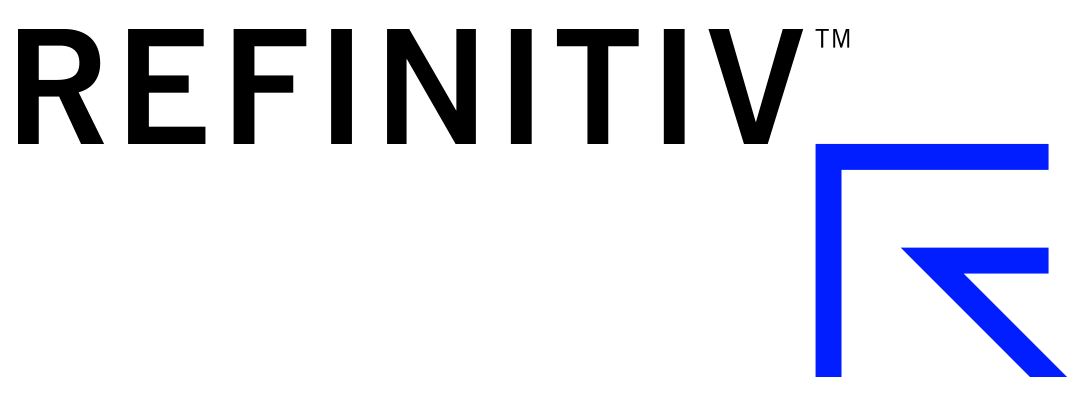

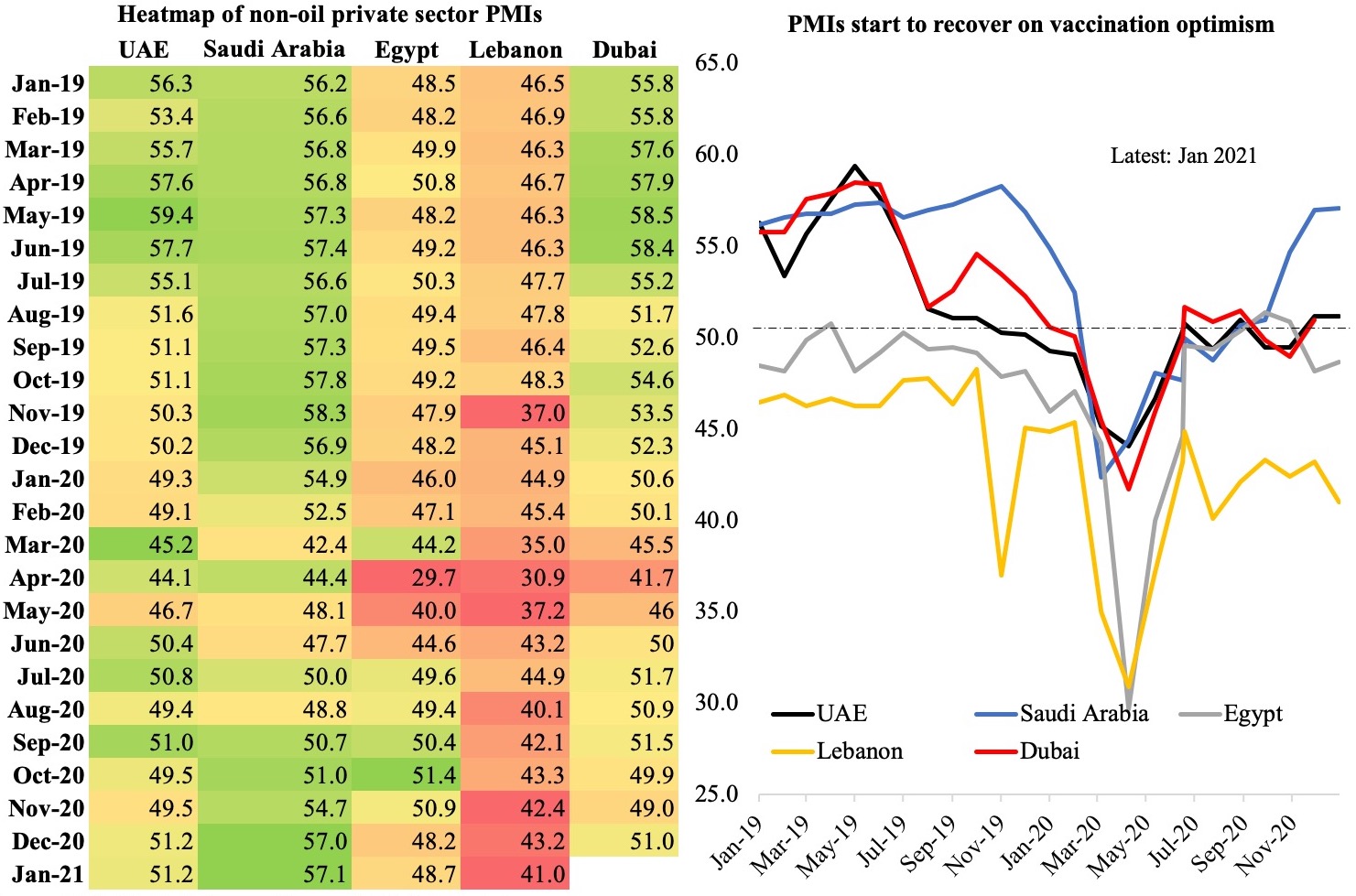

In the backdrop of the Covid19 pandemic, the UAE introduced many expat-friendly schemes to attract and retain a high-skilled workforce, essential to support its vision for the 4th Industrial Revolution future. Even if we consider the “expat exodus” from the country last year, there are silver linings: in early Nov, the Indian Ambassador revealed that more than 200k Indians were returning to the country (this compares to the 600k persons that travelled after May); PMI’s employment sub-category is finally in the expansion territory after months of sub-50 readings. Rather than focusing on inward facing nationalization policies, other GCC nations could take a leaf out of the UAE’s example to encourage job creation (including for their citizens). This would be an enlarge the cake, win-win policy as opposed to taxation of remittances.

Powered by: