Weekly Insights 20 Oct 2020: Expect a Protracted Economic Recovery in Middle East/ GCC

Download a PDF copy of this week’s economic commentary here.

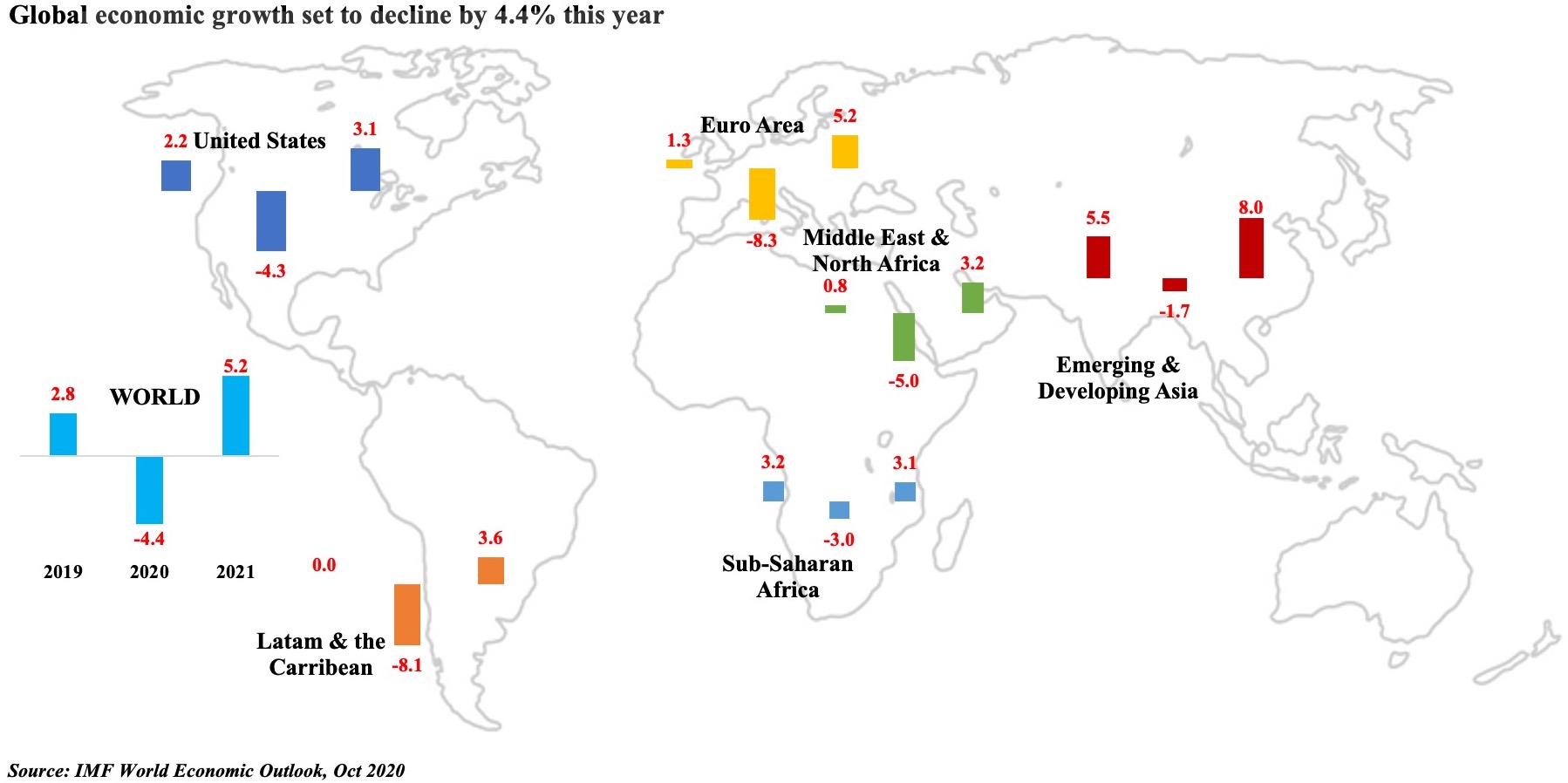

Fig 1. Global Economic Growth to decline by 4.4% this year, before rebounding to 5.2% in 2021

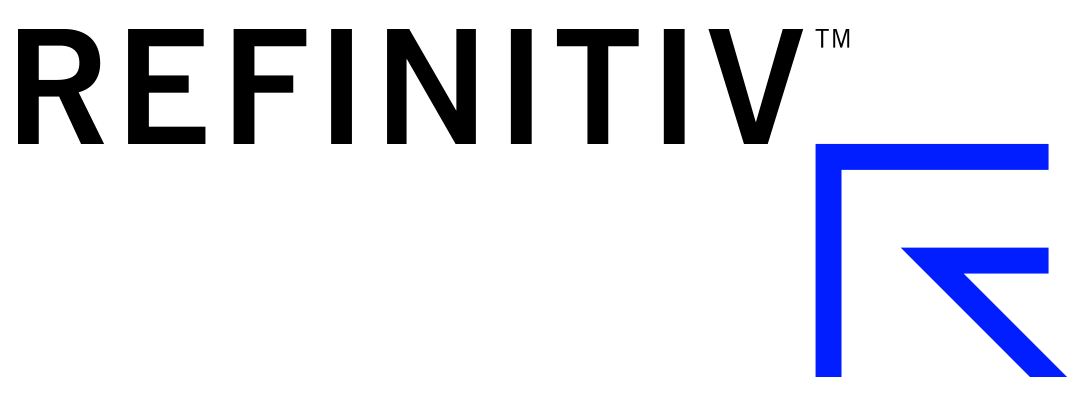

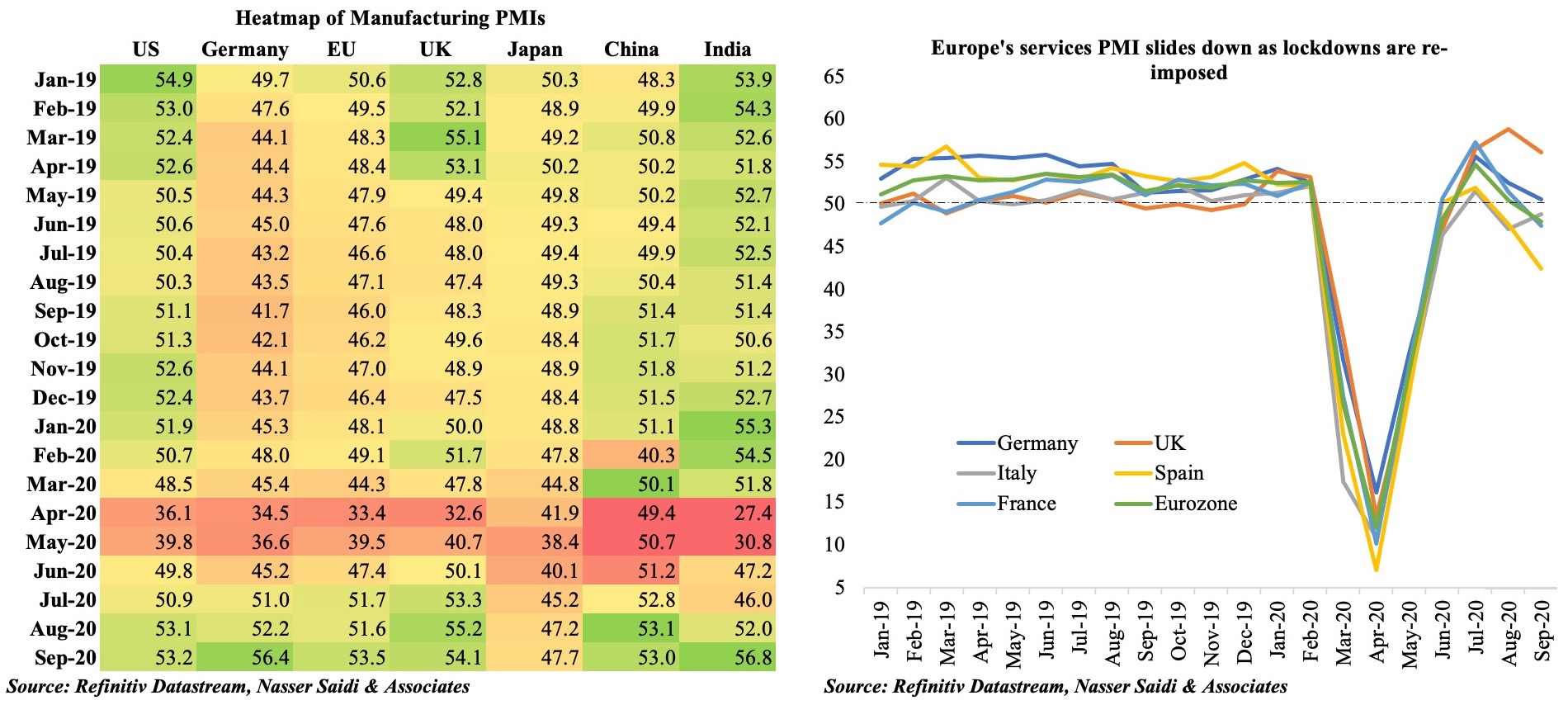

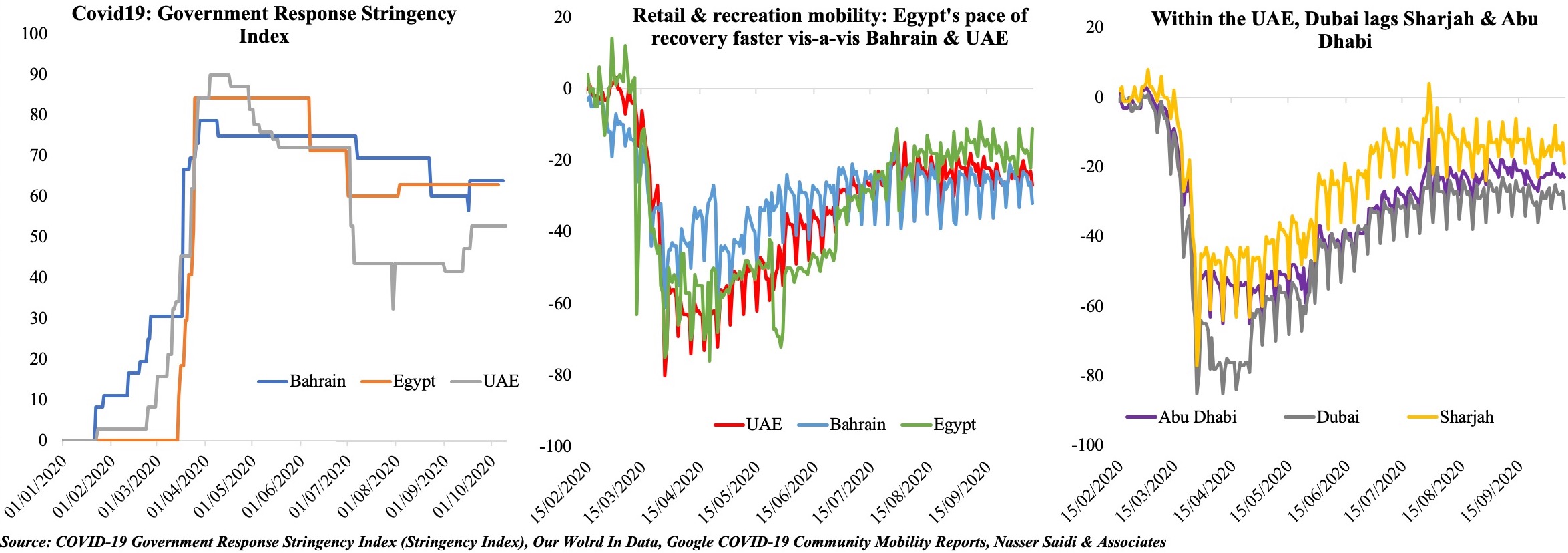

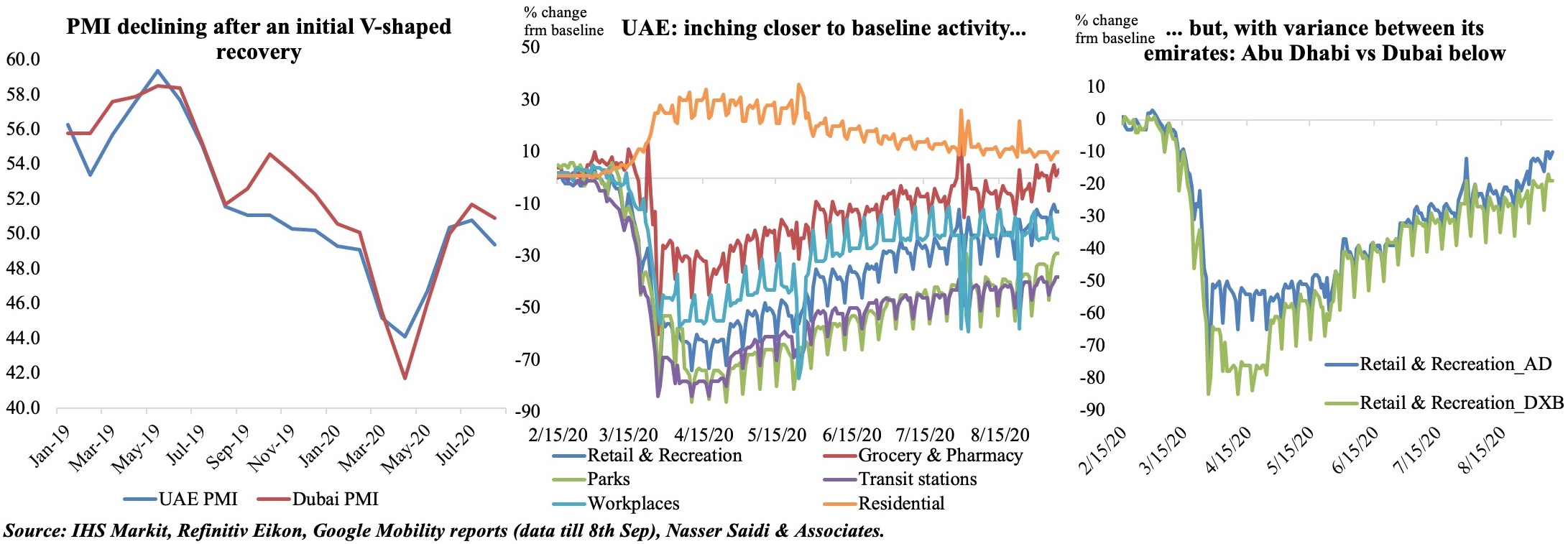

The IMF’s World Economic Outlook, released in October, forecast upwardly revised growth estimates for most country groups this year though stating that the recovery is “long, uneven and uncertain”. The IMF forecasts still seem relatively optimistic with all regional aggregates indicating a wobbly V-shaped recovery. Emerging markets and China are expected to recover much faster than their advanced counterparts while also noting that the plunge in growth was more severe for the advanced nations. A recovery in trade, PMI numbers and consumer spending are cited as supporting global recovery, though the sudden surge in Covid19 confirmed cases across Europe is likely to dampen the rebound, presaging a second wave and extended recovery.

Germany, Italy, Portugal and UK recently reported their highest number of infections since the start of the pandemic and many nations are reimposing restrictions – Belgium’s nationwide curfew, Switzerland making masks compulsory in indoor public areas, a 9pm curfew at many major cities in France – though a full-fledged lockdown is likely to be avoided. While Q3 may show an uptick in growth, Q4 is likely to slide back into negative territory (though not as sharp as Q2’s plunge). Mobility indicators how a decline in footfall across many European cities (https://on.ft.com/2TmvOkZ); PMI data reveals a divergence between manufacturing and services, with the latter reporting a drop in Sep. As we enter the cold winter months, the partial recovery seen in Q3 may be just temporary.

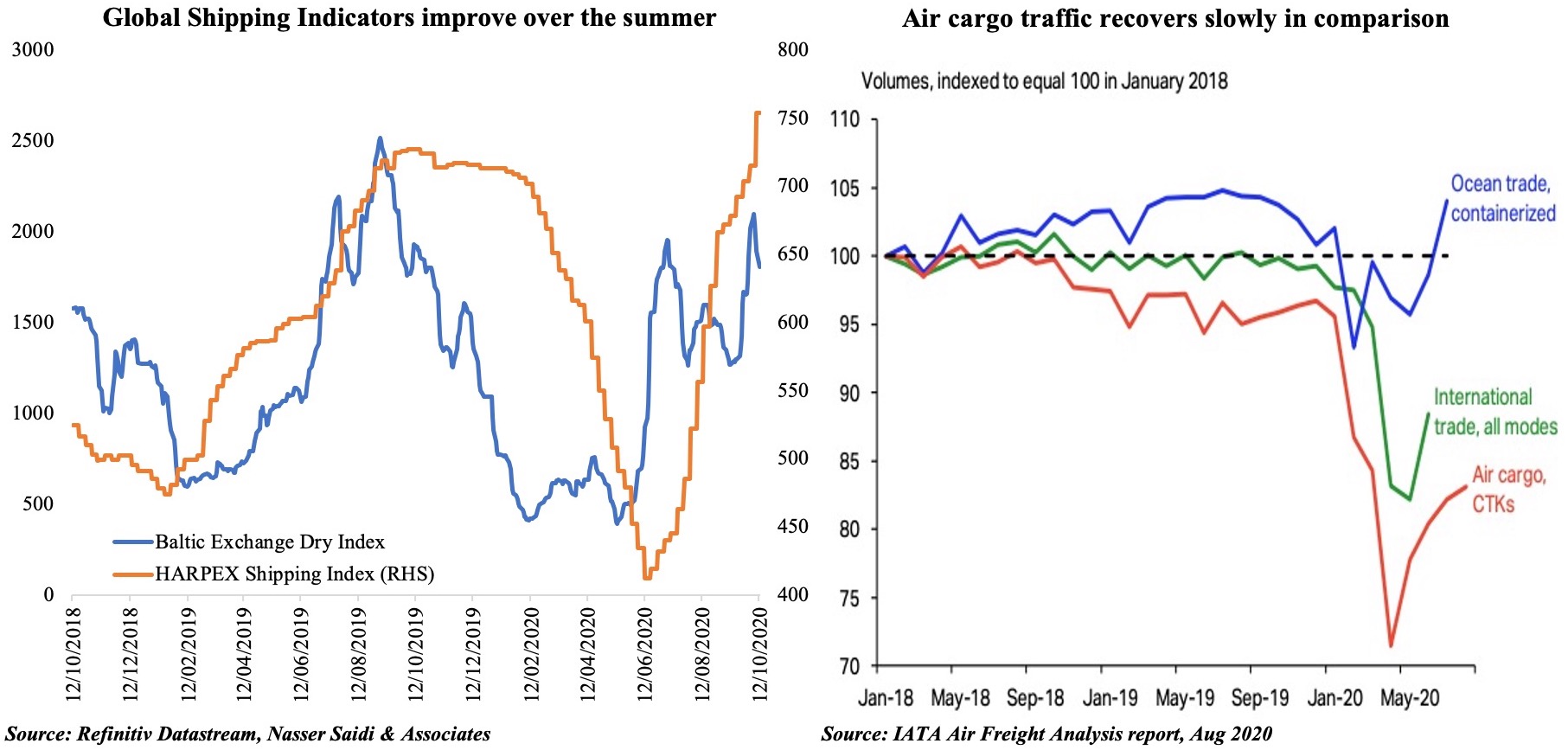

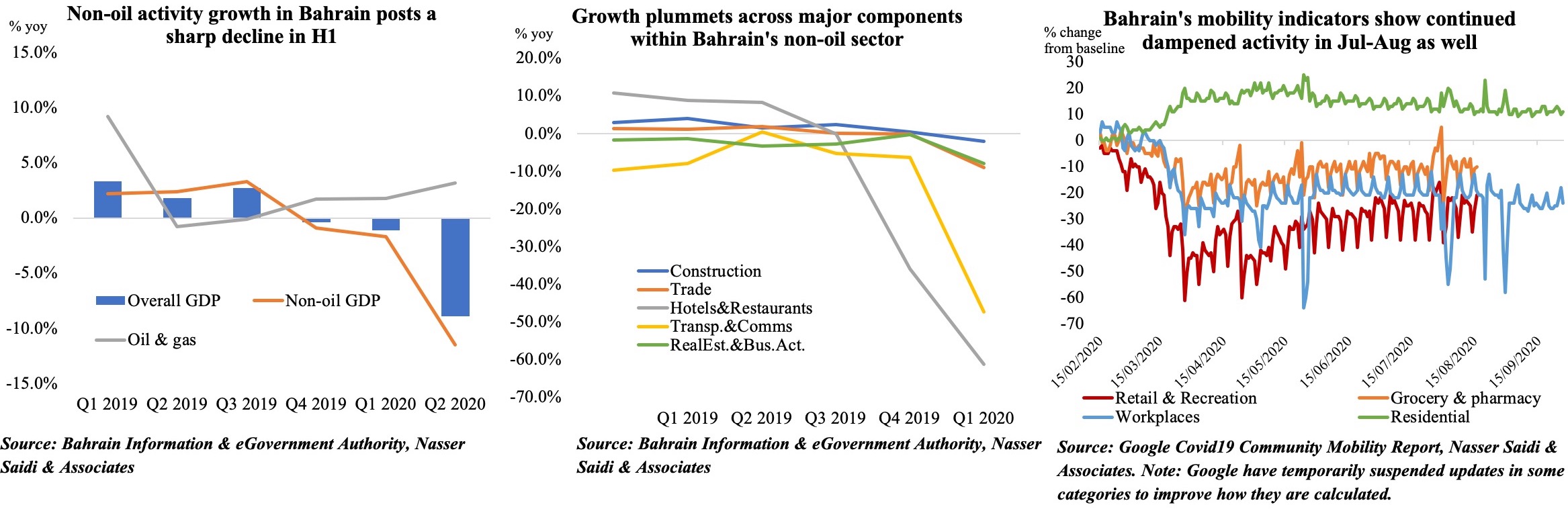

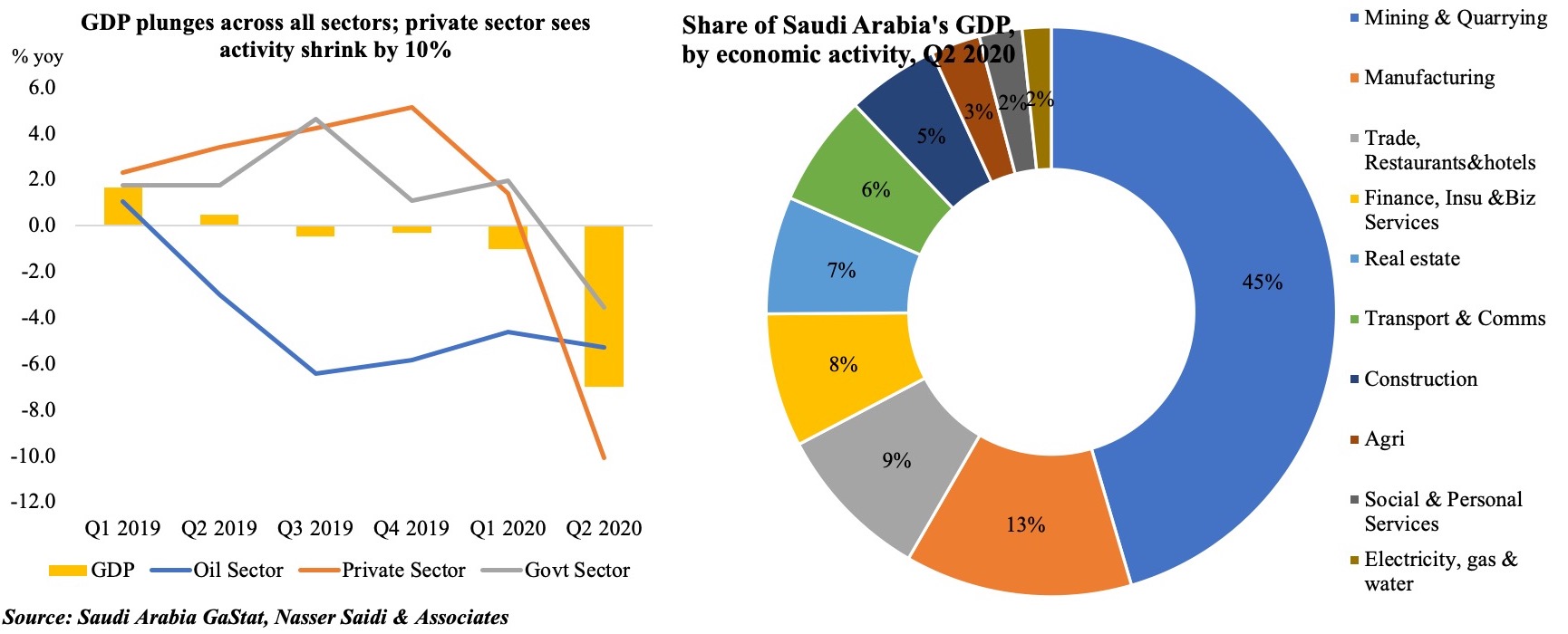

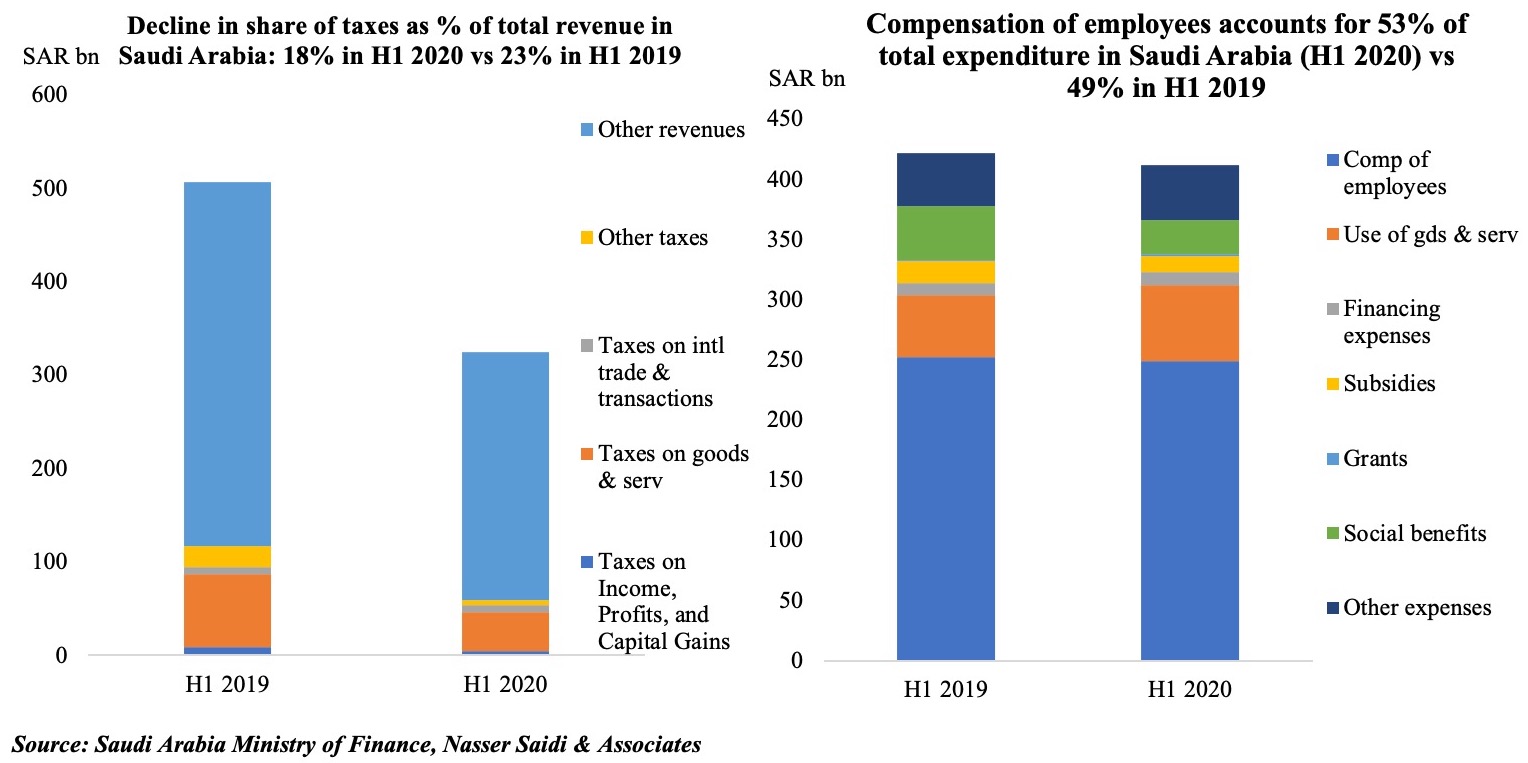

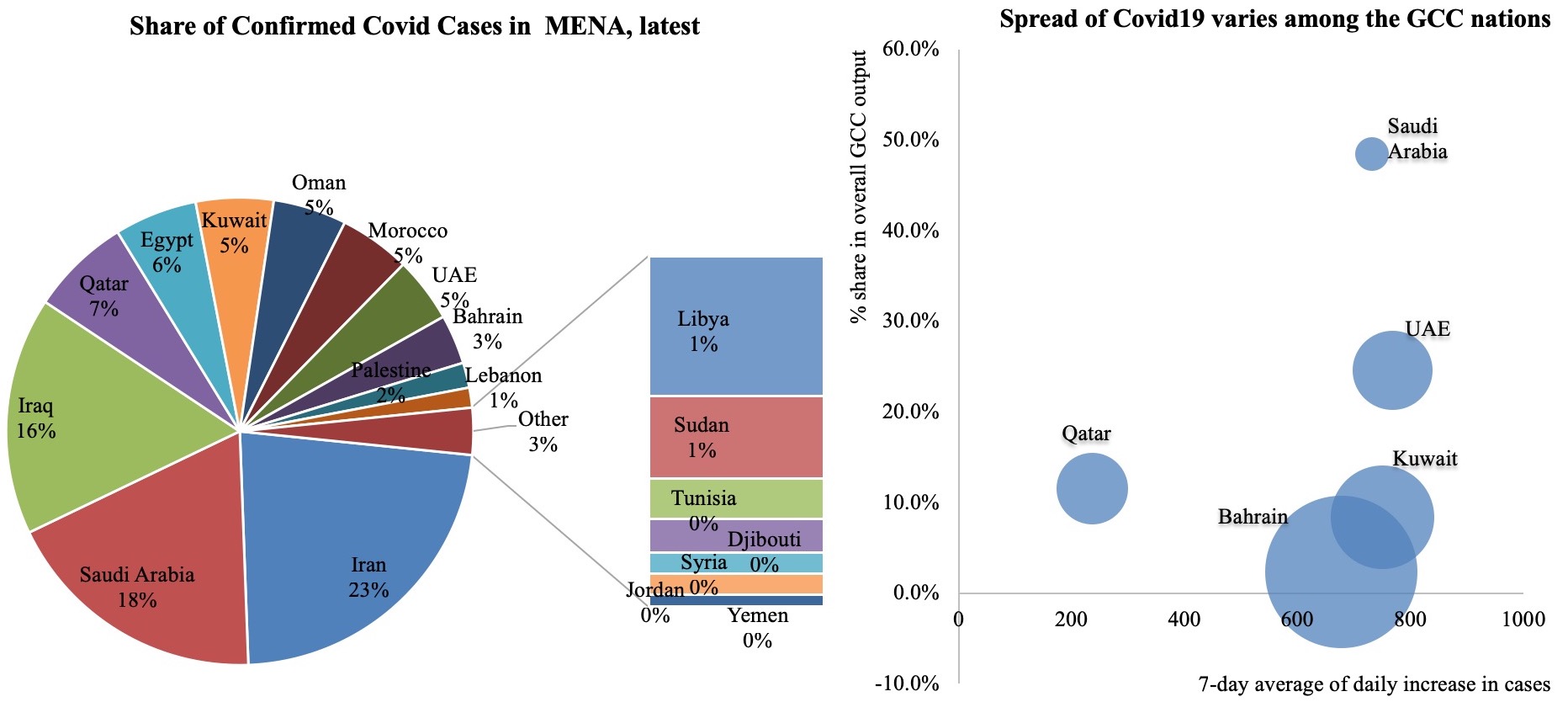

In the Middle East and North Africa (reeling from the effects of the global recession, Covid19 impact and oil exporters facing lower oil prices and demand), growth is expected to recover a tad later and slower compared to the rest, rising to only 3.2% from a 5.0% dip this year (Source: IMF Regional Economic Outlook: Middle East & Central Asia, Oct 2020). Egypt is the only country in the region forecast to grow this year (+3.5% yoy in spite of the massive decline in tourism). GCC growth is forecast to shrink by 6.0% this year – with oil and non-oil GDP contracting by 6.2% and 5.7% respectively.

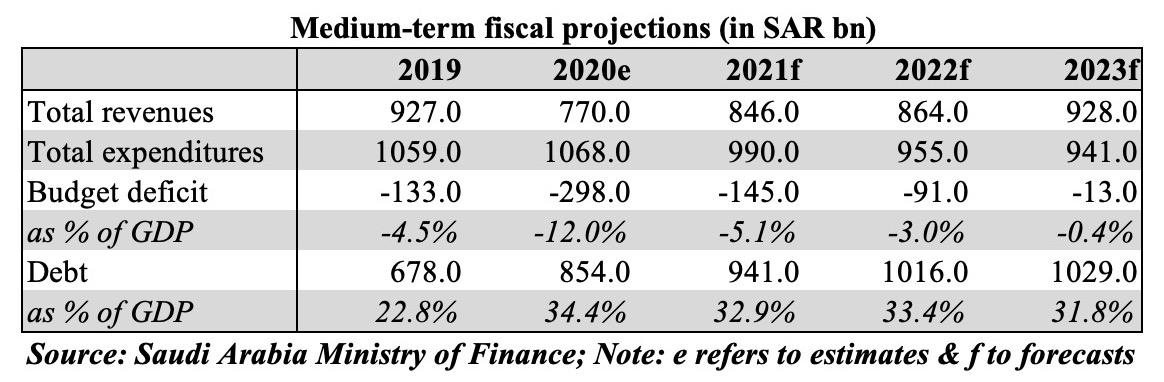

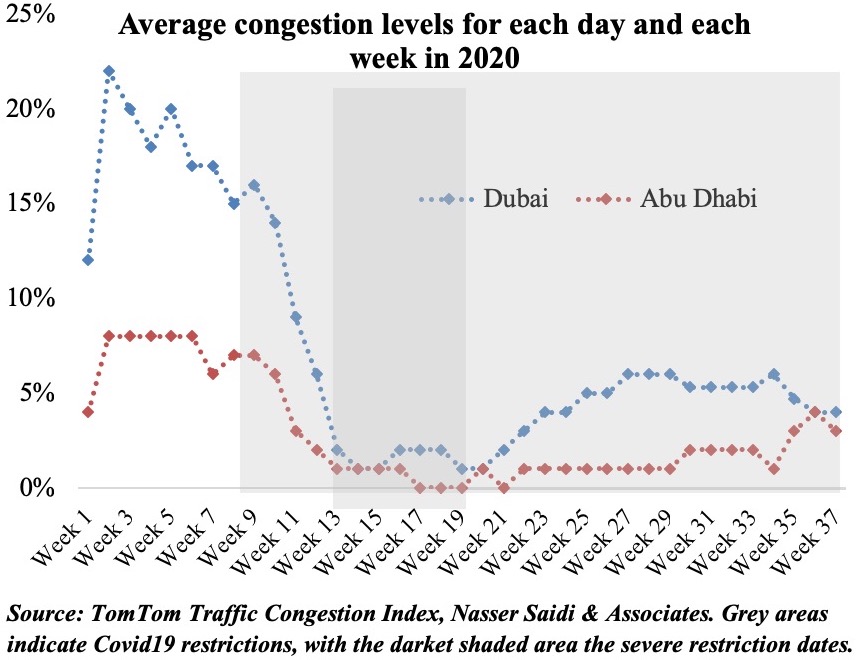

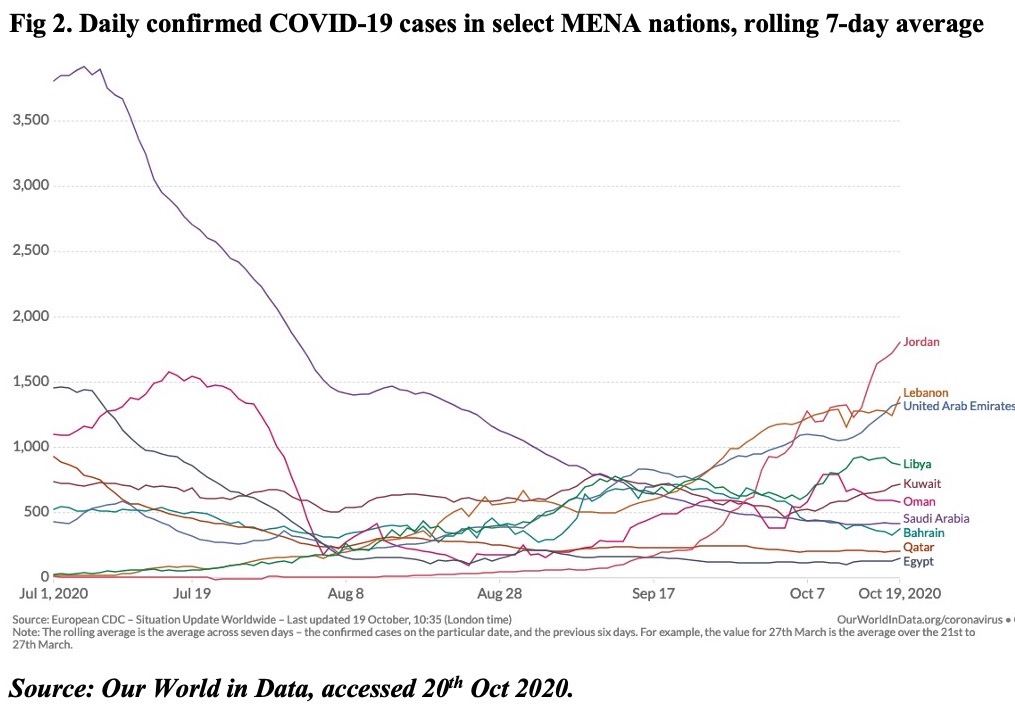

A recent uptick in Covid19 cases might add to economic uncertainty in the region – Jordan has reimposed some restrictions since the beginning of the month, but none of the nations have gone back to the stringency levels seen during Mar-Apr 2020. The immediate concerns remain on the fiscal side, with most nations rolling out stimulus packages to ease the impact from Covid19. For the GCC, fiscal deficits are projected at 9.2% of GDP this year (2019: -2%) while the fiscal breakeven oil price ranges from USD 42 for Qatar to USD 75.9 for the UAE and as high as USD 104.5 for Oman. Dependence on oil is still pronounced in spite of diversification efforts and the rising fiscal deficits are being met with a combination of debt issuances, tapping domestic markets, reduction of reserves and via sovereign wealth funds.

Though countries in the Middle East emerged from Covid-19 containment in Q2, the economic costs/ impact are likely to be protracted through the year and next given the many spillover risks: debt obligations and financing needs, job losses/ unemployment, potential NPLs affecting banking sectors, business closures leading to insolvency/ bankruptcy, and for the oil importers decline in remittances as well as rising poverty and inequality. IMF estimates foresee that five years from now countries could be 12% below GDP level expected by pre-crisis trends.

Powered by: