“MENA + Pakistan region faces $420–$510bn climate adaptation funding gap”, Interview with Zawya Projects, 7 Nov 2025

Dr. Nasser Saidi’s interview with Zawya Projects titled “MENA + Pakistan region faces $420–$510bn climate adaptation funding gap: CEBC Chief” was published on 7th Nov 2025.

MENA + Pakistan region faces $420–$510bln climate adaptation funding gap: CEBC Chief

In an exclusive interview with Zawya Projects, Dr. Nasser H. Saidi, Chairman and Founder of the Clean Energy Business Council (CEBC) MENA, explained why the MENA + Pakistan region must more than quadruple climate adaptation investment across infrastructure, and highlighted the GCC’s potential to become a global hub for renewable energy.

The Middle East, North Africa, and Pakistan (MENA+Pakistan) region must significantly increase investments in climate adaptation, particularly for retrofitting infrastructure, to an estimated $420 to $510 billion, the chief of UAE-based Clean Energy Business Council (CEBC) MENA told Zawya Projects.

Dr. Nasser H. Saidi, Chairman and Founder of the ADGM-based non-profit, which represents the clean energy sector pointed out that so far, the MENA+Pakistan region is discussing investments of around $100 to $120 billion in climate adaptation, which involves retrofitting current infrastructure, factories, and housing to be future-ready across the region.

“However, my estimate is that you need around four times that figure—to $420 to $510 billion—because Mother Earth has a mind of her own,” he said.

“Human actions have created climate challenges, and the earth responds. While we are not in charge of that, we must integrate climate models with our economic and planning models to design effective policies.”

And while numbers are still being assessed, the dynamics of climate change can be severe, he noted.

“We have to be preventive and preemptive when addressing climate risks; it concerns all our lives,” he said.

Dismal scenario

Saidi cited the disastrous floods in Libya in September 2023, where two dams collapsed in Derna after Storm Daniel, releasing 30 million cubic metres of water.

“The floods swept entire buildings, with thousands of people still inside them, into the Mediterranean Sea,” he explained. “This is a classic example of why the region needs to raise its investments in climate adaptation across its infrastructure and housing.”

“Climate change is a priority as we are very challenged by desertification, Medicanes, water scarcity, rising temperatures, and growing urbanisation and populations. So far, there have been many commitments and bright promises for net zero at the global level, but many of those pledges have not come through, and there has been dismal performance.”

Key challenges include securing enough financial resources from governments and attracting the private sector. Referencing the success of US railroads and post-war infrastructure development in Europe driven by private investment, Saidi emphasised that “whether we talk about energy, AI, data, or the digital economy, the bottom line is that the private sector will need incentives.”

He stressed the need to account for climate risk and pricing, making room for new, radically different technologies from the private sector.

“Much of the technologies that we inherited from industries like electricity, water, and transport have so far been managed by the public sector. It will have to be a combination of both because we have to plan at the national, regional, and global levels,” said Saidi, who is also the Founder and Head of Nasser Saidi & Associates, a consulting firm.

“All future planning should include the private sector, but with the framework and financing coming from the government and international institutions.”

He noted that the CEBC, which focuses on bringing together governments, regulators, and the private sector around climate finance, e-mobility, and energy efficiency, would be open to developing a climate fund, though its core mission remains as a not-for-profit platform to drive clean energy policy and dialogue.

“I would be open to anyone who says, let us develop a climate fund together,” he said.

Carbon pricing imperative

Regarding innovative funding instruments, Saidi suggested a gradual build-up. “In the end, we have to adopt carbon pricing, which means central banks, regulators, and governments have to introduce carbon pricing in everything—be it energy, water, the way companies perform, the balance sheets of banks, and central banks.”

Following the Great Financial Crisis, international banking regulations introduced measures such as the establishment of capital buffers.

It also saw the implementation of Basel III—a set of enhancements developed in response to the 2008 crisis—and subsequently Basel IV (the finalisation of Basel III), which overhauls global banking capital requirements, which is expected to significantly impact the lending landscape, particularly across Europe and the Nordic region.

“We need something equivalent to that in this area,” said Saidi, a former Lebanese Minister of Economy and Industry and former Vice Governor of the Lebanese Central Bank.

“It is only when you start pricing that people respond—not just good wishes,” he said, stressing that carbon pricing must eventually be integrated into the banking and financial system structure.

“Once you do that, you create opportunities for financing. But then again, you have to think long-term. Then the next question is, how do you control risks for infrastructure projects spread over a period of 15-20 years?”

“This is why pricing is so important. I am a strong believer in markets, so we need to create renewable funds and create markets where you can trade risks, particularly through financial markets,” he added.

The UAE’s Federal Decree on climate change, coming into force this year, mandates monitoring and control of GHG emissions across sectors while encouraging companies to participate in emission trading schemes and carbon credit markets. The country is also introducing carbon compliance regulations for eventual compliance markets.

Following the Great Financial Crisis, the world has also seen the rise of non-banking financial intermediaries, now providing almost 50 percent of the credit. “That creates its own risks. Hence, we have to involve the non-banking private sector, which consists of private credit and private funds, with the organised, regulated banking and finance sector—we have to look at the whole spectrum.”

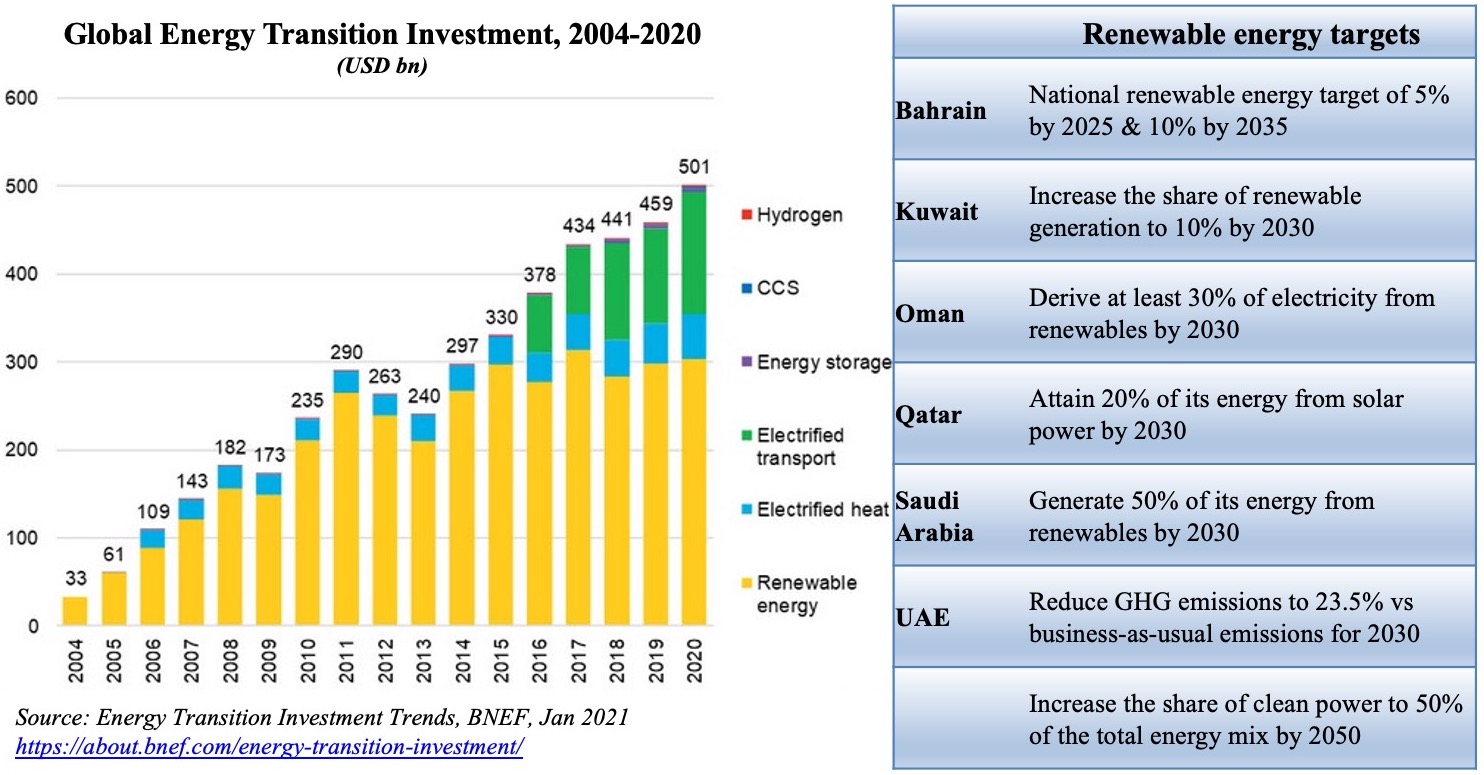

Global hub for renewable energy

While regional commercial banks do not always have the teams to assess such projects, the MENA region benefits from being awash with sovereign wealth funds and national funds.

“Hence, it would be ideal if they become involved because green and renewable energy is where the GCC, in particular, has a comparative advantage,” he said, arguing that deploying public money makes sound economic sense as part of economic diversification.

“We have accumulated enormous wealth due to high energy prices, and hence, we can deploy that wealth in green, digital, and renewable initiatives, and it can create jobs. So you diversify and develop your economy, and, at the same time, it is critical for the GCC and the region to create jobs. So this is the perfect opportunity for us.”

“This region is already the global hub for oil and gas,” Saidi concluded. “This region also has the potential to be the global hub for renewable energy. No other country or region has that combination.”