The article titled “Saving the Lebanese Financial Sector: Issues and Recommendations”, written by A Citizens’ Initiative for Lebanon was published on 15th March, 2020 in An Nahar and is also posted below.

Saving the Lebanese Financial Sector: Issues and Recommendations

In order to restore confidence in the banking sector, the government and the Banque du Liban (BDL) need a comprehensive stabilisation plan for the economy as a whole including substantial fiscal consolidation measures, external liquidity injection from multi-national donors, debt restructuring and a banking sector recapitalisation plan. Specifically, the Lebanese banking sector which will be heavily impaired will have to be restructured in order to re-establish unencumbered access to deposits and restart the essential flow of credit. A task force consisting of central bank officials, banking experts and international institutions should be granted extraordinary powers by the BDL and the government to come up with a detailed plan which assesses the scale and process for bank recapitalisation and any required bail-in; identifies which banks need to be supported, liquidated, resolved, restructured or merged; establish a framework for loss absorption by bank shareholders; consider the merits of establishing one or several ‘bad banks’; revise banking laws; and eventually attract foreign investors to the banking sector. In the meantime, we would recommend the imposition of formal and legislated capital controls in order to ensure that depositors are treated fairly and also ensure that essential imports are prioritised.

How deep is Lebanon’s financial crisis?

The financial crisis stems from a combination of a chronic balance of payments deficits, a liquidity crisis and an unsustainable government debt load which have impaired banks’ balance sheets, leaving many banks functionally insolvent.

Even before the government announced a moratorium on its Eurobond debt on March 7th, public debt restructuring was inevitable, as borrowing further in order to service the foreign currency debt was no longer possible and, dipping into the remaining foreign currency reserves to pay foreign creditors was deemed to be ill-advised given the priority to cover the import bill for essential goods such as food, fuel and medicine. Moreover, with more than 50 percent of fiscal revenue dedicated to debt service in 2019, debt had clearly reached an unsustainable level.

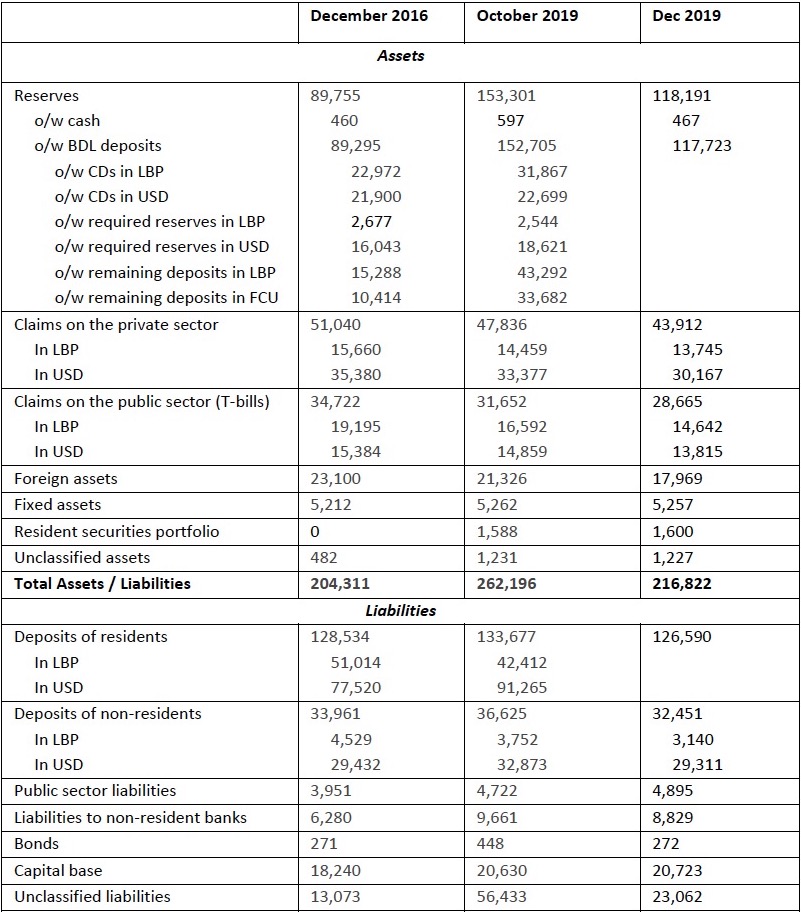

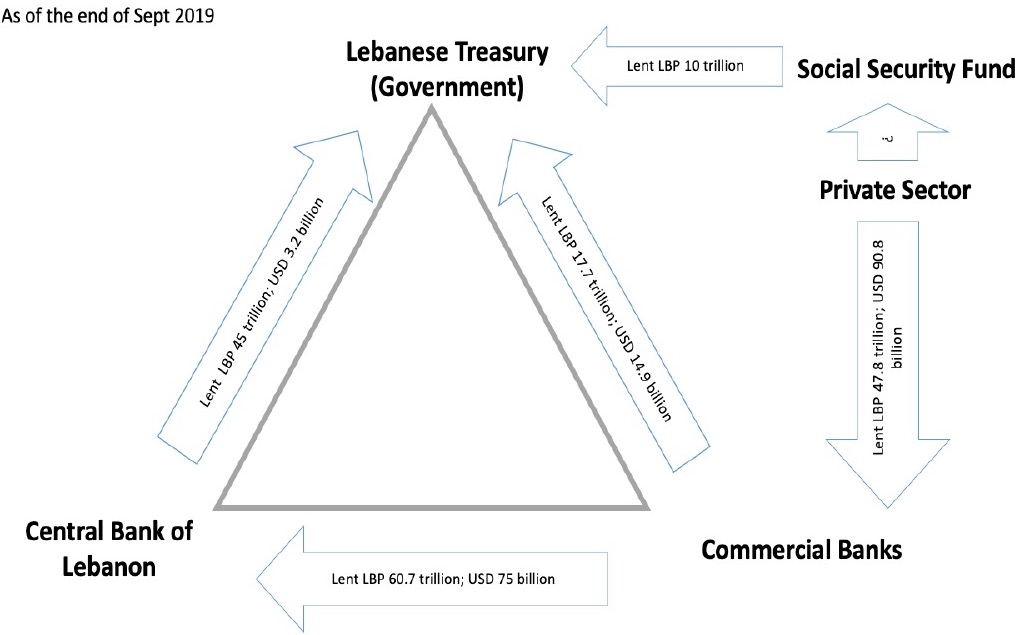

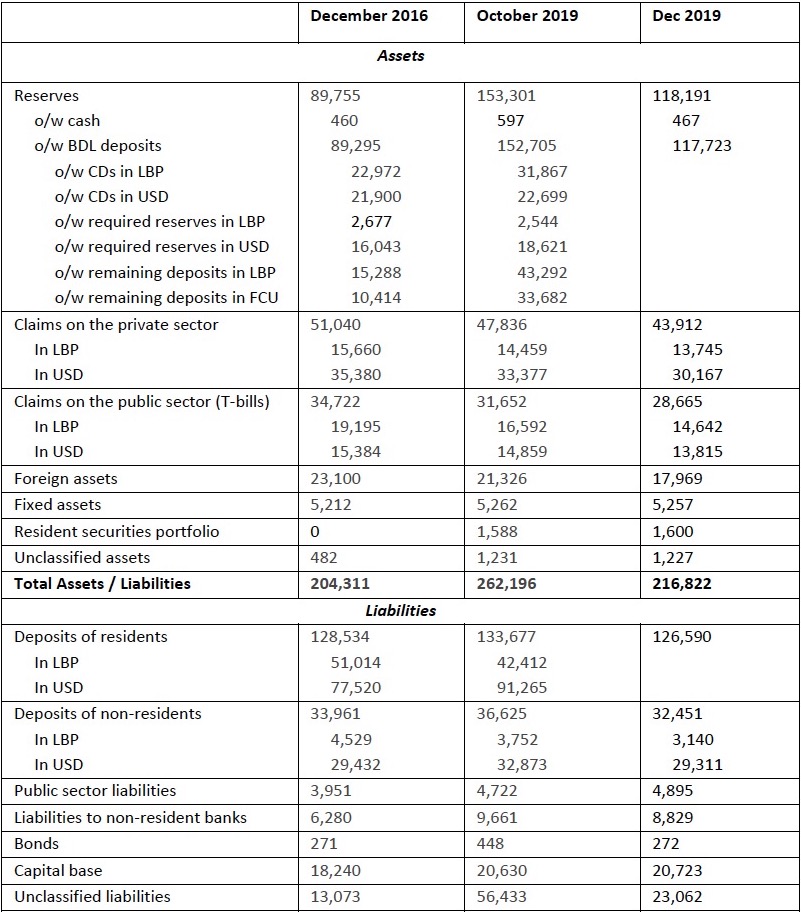

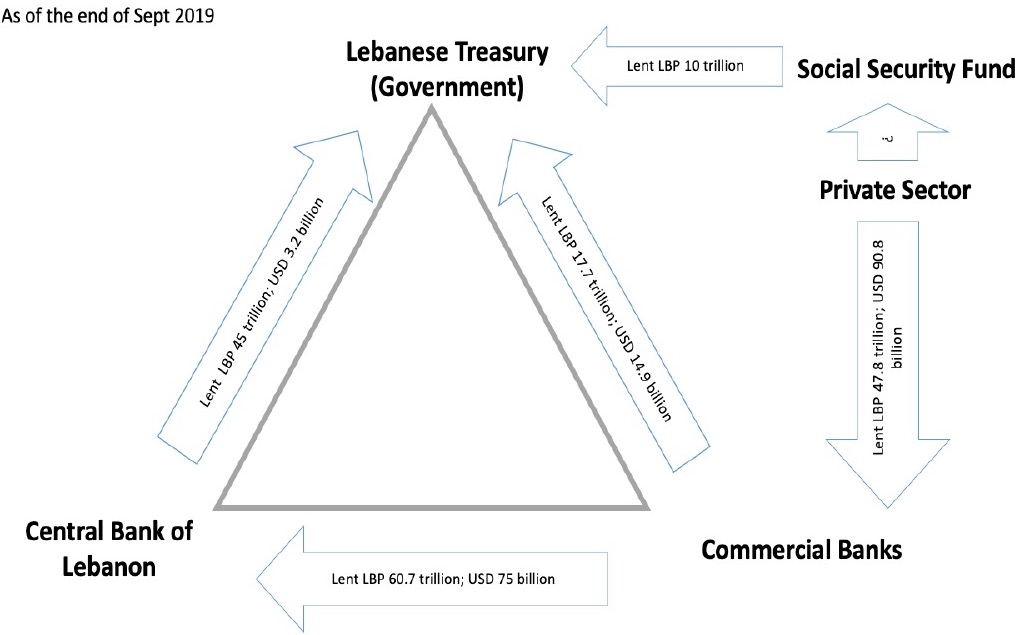

At the end of December 2019, banks had total assets of USD 216.8 billion (see Table 1). Of these, USD 28.6 billion were placed in government debt, and USD 117.7 billion were deposits (of various types) at BDL, which is itself a major lender of the government (see Figure 1 for the inter-relations between the balance sheets of the banks, the central bank, and the government). Banks also hold more than USD 43.9 billion in private loans. Already, the banking association is assuming that approximately 10 percent of private sector loans, such as mortgages and car loans, have been impaired due to the economic crisis. Other countries facing similar financial and economic crises have experienced much higher non-performing loan rates. For instance, the rate rose to above 35 percent in Argentina in 1995 and neared 50 percent in Cyprus in 2011.

Well before the decision to default however, Lebanon’s banks have had limited liquidity in foreign currency and have been rationing it since last November, as the central bank was not releasing sufficient liquidity back into the banking system. Even banks that have current accounts with the Banque du Liban do not have unfettered access to their foreign currency deposits. The BDL has had to balance a trade-off between defending the Lebanese pound peg, releasing liquidity or continuing to finance government fiscal deficits and has chosen to prioritise maintaining the peg and covering the country’s import bill.

Table 1: Consolidated commercial bank balance sheet (USD million)

Source: Banque du Liban. (2019). Consolidated Balance Sheet of Commercial Banks. Retrieved from https://www.bdl.gov.lb.

Note: In December 2019, commercial banks have netted the results of the swap operations with BDL, thus explaining the large swing in Reserves (asset side) and Unclassified liabilities.

Reducing public debt to a sustainable level will require deep cuts in government and central bank debts. This in turn will have a significant impact on bank balance sheets and regulatory capital. For most banks, a full mark-to-market would leave them insolvent. To avoid falling short of required capital standards, BDL has temporarily suspended banks’ requirements to adhere to international financial reporting standards. But suspending IFRS cannot continue for a long period, as it effectively disconnects the Lebanese banking system from the rest of the world.

What will be the impact of the sovereign default on the banking sector?

Today, Lebanese banks are not able to play the traditional role of capital intermediation by channelling deposits towards credit facilitation. In most financial crises, public authorities are able to intervene to recapitalise the banks and central banks are able to intervene to provide liquidity. Unfortunately, in Lebanon, the state has no fiscal ammunition and the central bank is itself facing dwindling foreign exchange reserves. This leaves the banks in a highly precarious situation.

In a sovereign restructuring scenario where we assume a return to a sustainable debt level of 60% debt to GDP ratio and a path to a primary budget surplus, depending on the required size of banking sector in a future economic vision for the country, we estimate the need for a bank recapitalisation plan to amount to $20 to $25 billion to be funded by multi-lateral agencies and donor countries, existing and new shareholders, and a possible deposit bail-in. Under all circumstances, we strongly advocate the protection of smaller deposits. In addition, special care has to be taken during any bail-in process to (i) provide full transparency on new ownership; (ii) avoid concentrated ownership; and (iii) shield the new ownership from political intervention either directly or indirectly. It is also worth noting that additional amounts of capital will be required to jumpstart the economy and provide short term liquidity.

Leaving the banking sector to restructure and recapitalise itself without a government plan would take too long and Lebanon would turn even more into a cash economy, with little access to credit, little saving, low investment, and low or negative economic growth for years to come. Economic decay would ultimately lead to enormous losses for depositors, and serious hardship to the average Lebanese citizen.

What should be the goal of financial sector reforms?

The primary goal of financial sector interventions must be to restore confidence in the banking sector and restart the flow of credit and unrestricted access to deposits. In addition to rebuilding capital buffers and addressing the disastrous state of government finances, we would advocate reforming the financial sector in order to avoid banks’ over-exposure to the public sector in the future, incentivising them to lend instead to the real economy. This must include a prohibition of opaque and unorthodox financial engineering and improving banks’ capacity to assess local and global markets.

Confidence in the financial sector will also require a strong and independent regulator. Lebanon has a unique opportunity in that regard as there are 13 vacancies in the regulatory space that need to be filled by end of March: four vice governors of the Banque du Liban, five members of the Commission of Supervision of the Bank (current members due to leave by end of March), three Executive Board members of the Capital Markets Authority, and the State Commissioner to BDL. These nominations should be completed following a transparent process shielded from political and sectarian influence ensuring candidates possess the requisite competencies.

In addition to these nominations, a revamp of the governance of the regulatory institutions has to be undertaken following a thorough review. In order to enhance risk management and avoid a repeat of concentrated lending in the future, the monetary and credit law should be amended to prohibit excessive risk taking related to the government, which will have the double benefits of forcing a more disciplined sovereign borrowing program and encourage a more diversified use of bank balance sheets directed at more productive areas of the real economy. Providing a framework to curtail so-called “financial engineering” transactions should also be addressed in order to discourage moral hazard and enhance the transparency and arms-length nature of any such operations in the future.

Finally, any future model will also require a migration towards a floating currency, and revised tax and financial sector laws and regulations, encouraging greater competition including from foreign banks. It is worth noting that while a devaluation of the LBP would have a positive direct effect on the balance sheet of banks, it would hurt their private sector borrowers, as most of these loans are dollar denominated, and thus, would lead to higher level of NPLs, hurting banks through second order effects.

Figure 1: Net obligations of Lebanese government, central bank, commercial banks and social security fund (as of September 2019 due to lack of some data as of December 2019).

How do we restructure the financial sector?

Saving the financial sector will require empowering a task force consisting of BDL officials, BCCL officials, independent financial sector experts, and Lebanon’s international partners, including multilateral-agencies.

Bank equity should be written down to reflect the reality of asset impairment with existing shareholders being allowed to exercise their pre-emptive rights to recapitalize banks with their own resources or by finding new investors, thus reducing the burden on the public sector, multilateral agencies, donors or depositors. Certain banks could be wound down or resolved by the government. Banks that are liquidated or placed into resolution would transfer control to the government, though current bank administrators can remain in place so that regular business transactions can continue. Some banks may be too small to consider “saving’ and should go into liquidation.

The purpose of this process would be to restructure (or wind down) insolvent institutions without causing significant disruption to depositors, lenders and borrowers. The first step in the resolution process is for shareholders and creditors to bear the losses in that order. If the bank has negative equity after this stage, it can begin by selling key assets, such as real estate or foreign subsidiaries before resorting to a capital injection.

One potentially useful tool to support asset sales and re-establish normal banking activities quickly would be to create a ‘bad bank’ consisting of the bank’s non-performing loans or toxic assets. A ‘bad bank’ makes the financial health of a bank more transparent and allows for the critical parts of the institution to continue operating while these assets can be sold. Bad banks have been used in France, Germany, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States, among others, to address banking crises similar to the current Lebanese situation. ‘Bad banks’ can be established on a bank-by-bank basis, managed by the bank itself (under government stewardship) or by the government on a pooling basis. The challenge in Lebanon is neither the BDL nor the largest banks have sufficient capital buffers to fund the equity of such a bad bank.

If the bank equity remains in the red once key assets have been sold (or transferred to a ‘bad bank’), absent sufficient recapitalisation funds, a bail-in may be considered. A bail-in refers to shrinking of the bank’s liabilities, consisting mainly of deposits, by converting a portion into bank equity.

Nationalization is impractical in the Lebanese context. While transferring control of operations away from bank management teams that have lost credibility will be necessary, nationalization is impractical in the Lebanese context since the government is effectively insolvent. Also, state-owned banks may be used to further serve political interests and can be easily misdirected and mismanaged by becoming platforms for politically motivated lending, hiring and pricing.

Does Lebanon need fewer banks?

We believe that a market like Lebanon requires fewer banking institutions and a round of consolidation is imperative to make the system more robust and competitive as well as more diversified business models in order to serve a broader spectrum of economic activity. Mergers will require first full clarity on banks’ financials. As such, this crisis could be seized upon to achieve this outcome. Academic research in this area confirms that while bank consolidation can lead to higher fees and potentially higher loan rates, it also provides greater financial stability and less risk taking. Larger banks can also attract investors more easily, especially high-quality long-term shareholders.

In most countries experiencing a financial crisis, those banks that are overexposed to troubled assets have been absorbed into large healthy banks. However, in Lebanon, as most large banks are heavily exposed to central bank and government debt and non-performing loans they are unable to play the consolidator role. We therefore believe that a consolidation can be best achieved by a combination of unwinding smaller banks, resolving some banks and merging larger banks which would facilitate new equity fundraising, and cost cutting with fewer branches required in an increasingly digital world. Larger banks will also be able to afford to invest in newer IT systems and risk management systems over time and be viewed as better credits by foreign correspondents.

Conclusion. The solutions exist, the time to act is now!

Signatories (in their personal capacity)

Amer Bisat, Henri Chaoul, Ishac Diwan, Saeb El Zein, Sami Nader, Jean Riachi, Nasser Saidi, Nisrine Salti, Kamal Shehadi, Maha Yahya, Gérard Zouein

Institutional Endorsements

LIFE

Kulluna Irada