“Digital remittances will unlock financial inclusion in the Middle East”, Oped in The National, 21 Jan 2026

The article titled “Digital remittances will unlock financial inclusion in the Middle East” appeared in the print edition of The National on 21st January 2026 and is posted below.

Digital remittances will unlock financial inclusion in the Middle East

Nasser Saidi

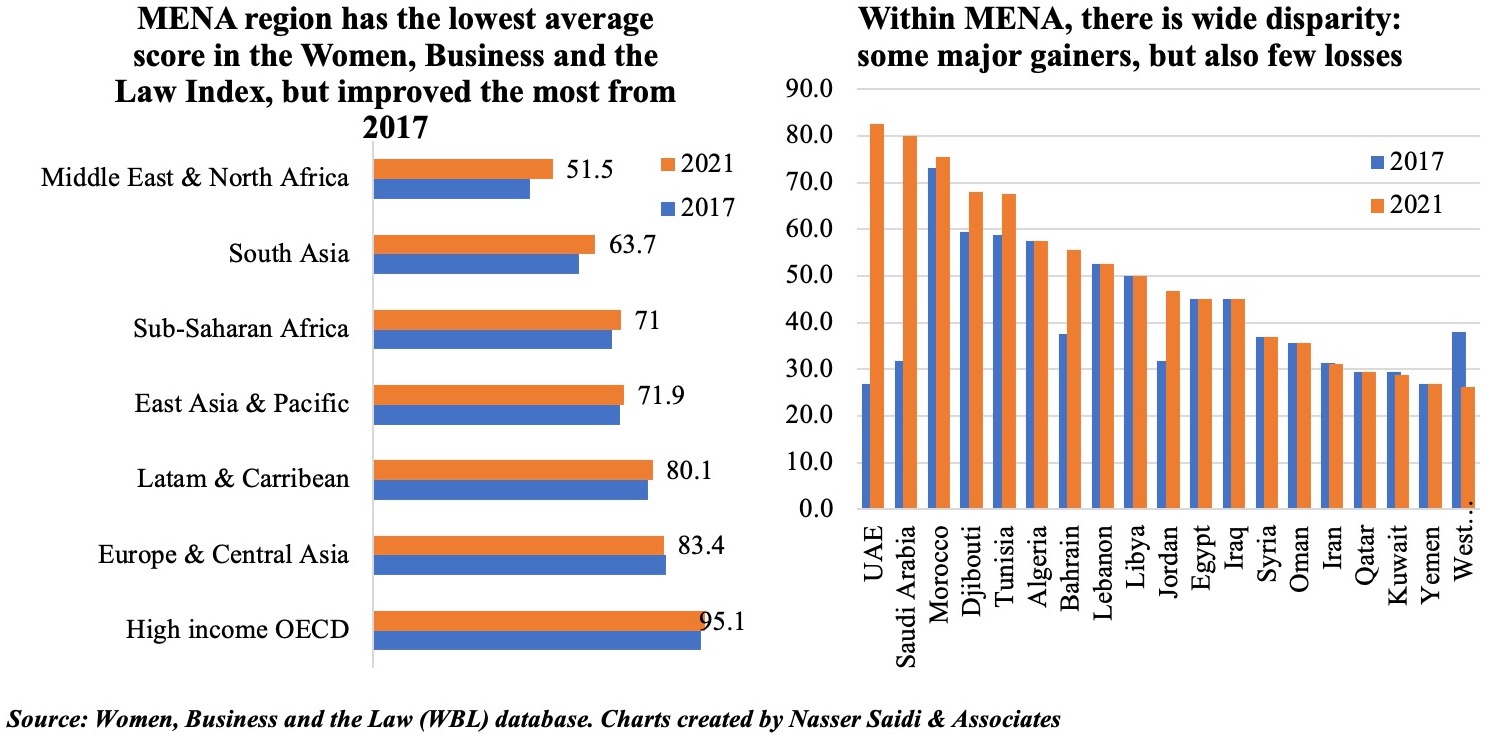

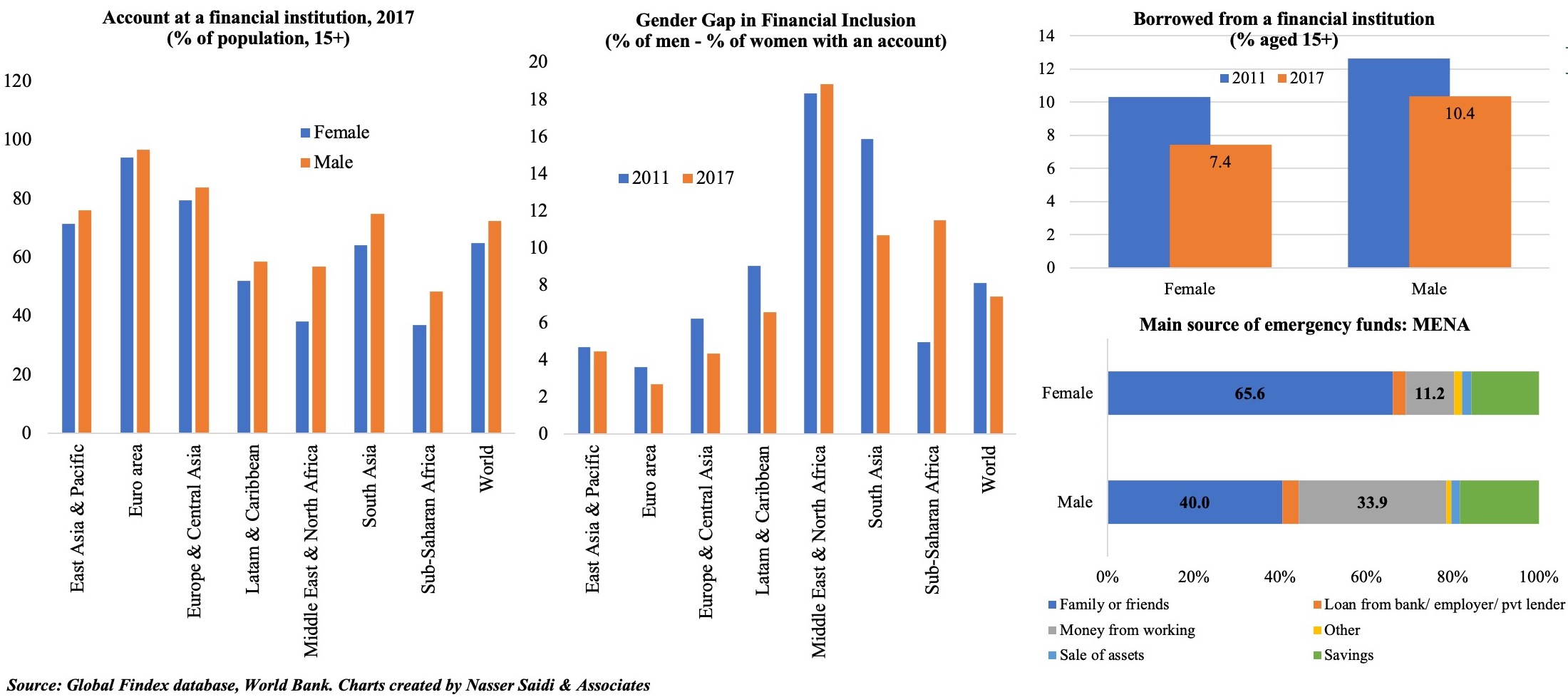

Financial inclusion remains a challenge for Arab countries in the Middle East. Only 50 per cent of adults in the region have a financial account, the lowest global score in financial account ownership, the World Bank says.

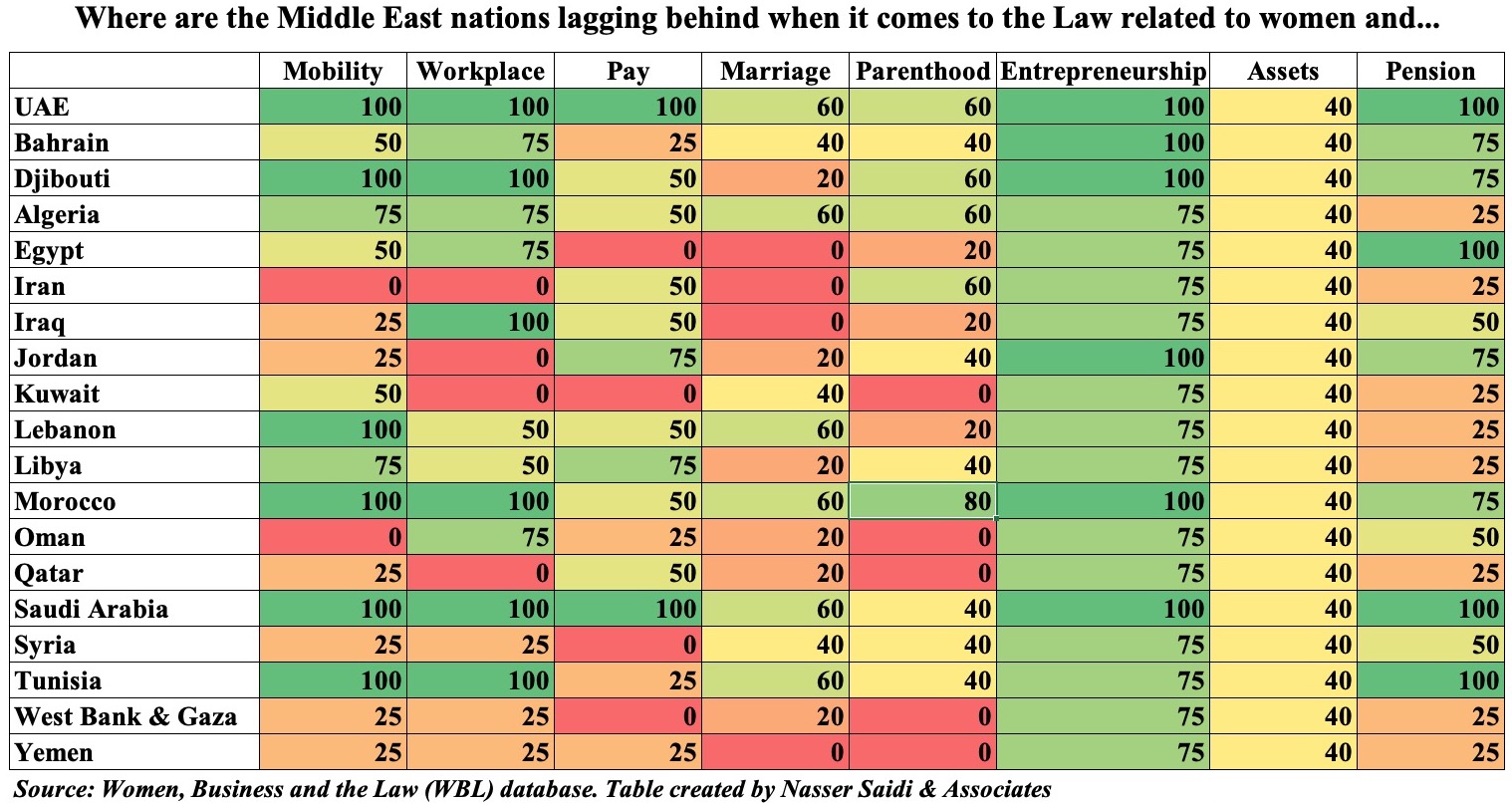

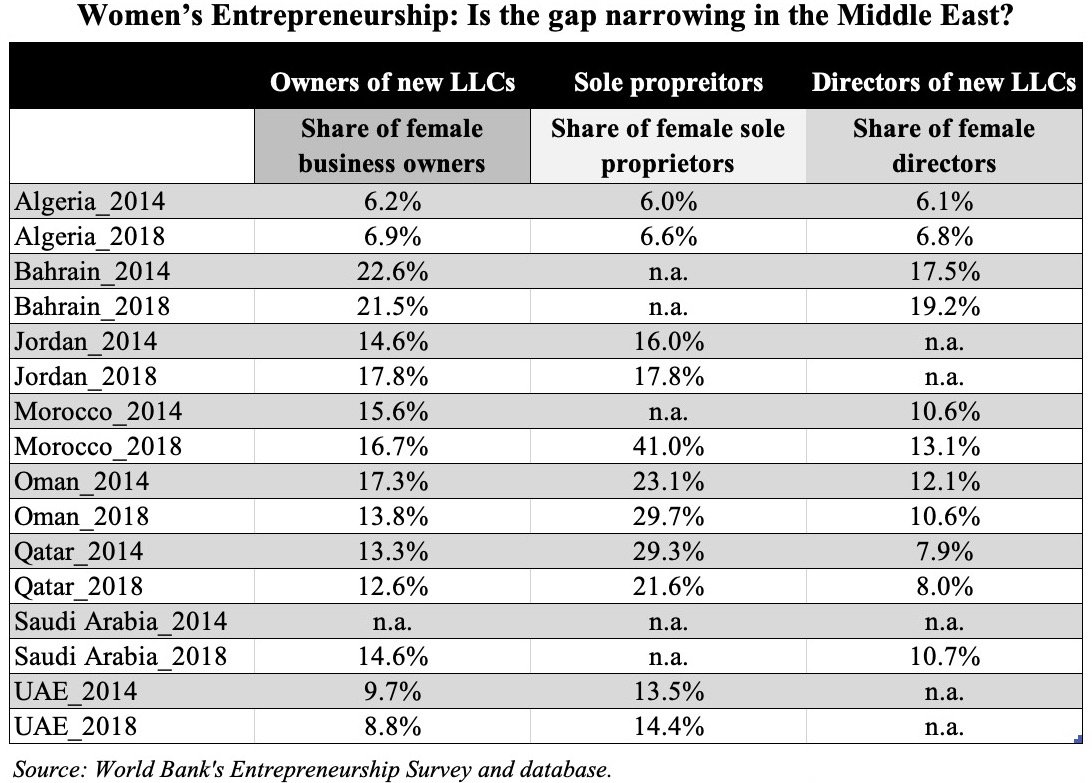

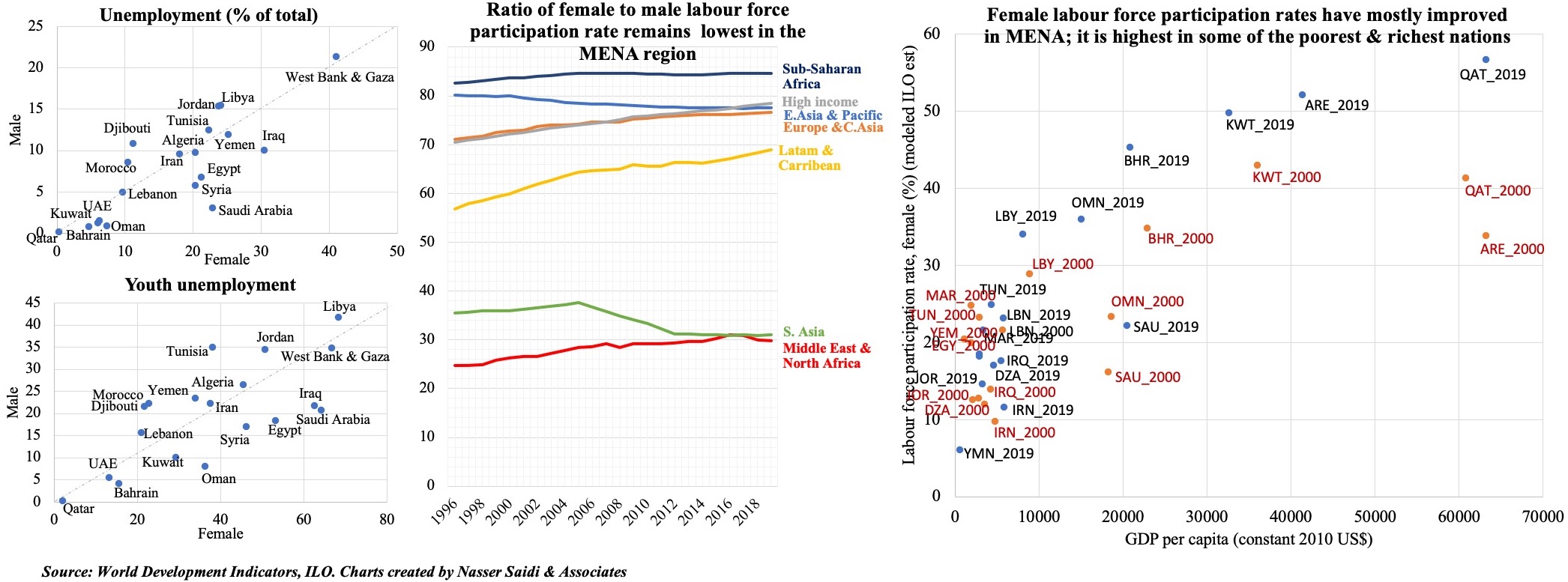

There are also wide gaps between the Gulf and the rest of the region, while women are disproportionately less likely than men to have accounts.

The gender gap in account ownership is most severe in the region, at 15 percentage points, more than double the average of other upper-middle-income countries.

Financial exclusion forces people into the informal cash economy, limiting their ability to save, invest and protect themselves from economic shocks. By contrast, globally, 78.7 per cent of people aged over 15 have an account with a bank, financial institution, or mobile money provider, up from 50.6 per cent in 2011.

Of the 1.3 billion adults that remained unbanked globally in 2024, the majority are located in the Arab region, Asia and Africa.

But digital technology is transforming the financial landscape. The Global Findex Digital Connectivity Tracker finds that 84 per cent of adults in developing economies own a mobile phone (in the Middle East and North Africa, it is a higher 89.3 per cent). Mobile phones and internet connectivity allow more people to access and use digital financial services. Mobile money accounts are gaining popularity as an alternative means of accessing financial services, with 2.1 billion registered mobile money accounts globally in 2024, according to the GSMA.

The Middle East is a global hub for migration, characterised by a unique demographic flow.

The Gulf Co-operation Council-South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal) labour flow corridor is the single largest labour migration corridor into the Mena region.

Beyond South Asia, many migrants come from labour exporting Arab states such as Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria.

Remittance outflows from the Gulf clocked in at $131.5 billion in 2024, with $77 billion from Saudi Arabia and the UAE alone. For recipient countries such as Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, India and Pakistan, these flows are not merely supplementary income; they are vital economic stabilisers that often outstrip foreign direct investment and official development assistance.

In Lebanon, remittances have become a critical lifeline amid economic collapse, representing 27.5 per cent of gross domestic product and more than 80 per cent of total external resource flows in 2023.

Money to send money

The traditional channels for remittances are costly and slow. High fees erode the value: when a migrant worker pays 7 per cent or more to send money home, it acts like a tax on development, with the reliance on cash agents an additional source of uncertainty and security risks.

The digital space offers a transformative opportunity. Digital remittances are not just about cost, efficiency and convenience; they are a gateway to broader financial inclusion.

The Mena region is already embracing this: in 2024, only 9.1 per cent of respondents to the Global Findex survey used a bank account for sending or receiving domestic remittances, compared to 26.3 per cent by all means including money transfers.

Empirical evidence finds a positive correlation between remittances and formal deposits/ credits, and using accounts for such transfers leads to remitters sending on average 30 per cent more than via informal channels.

By bypassing physical networks and leveraging mobile technology, the cost of sending money can drop to below the UN Sustainable Development Goals target of 3 per cent.

Digital transfers are near-instantaneous and secure, while also reducing the risks associated with carrying cash. Importantly, using digital channels creates a financial footprint.

For a migrant worker or displaced person who has never had a bank account, a digital remittance history can be the first step towards accessing credit, insurance and savings products. The success stories of M-Pesa in Kenya and Jazz Cash in Pakistan highlight mobile money services that have revolutionised financial inclusion by leveraging high mobile phone penetration – sporadic internet access is not a limiting factor in such cases. Both digital platforms have since expanded beyond simple transfers to offer loans, savings, insurance and merchant payments.

These models can be easily introduced in the Mena region, especially given the migration and expatriate labour patterns.

Users in Morocco are embracing digital payments, with various international money transfer operators present in the country (eg, Wise, Remitly, Xoom etc), and government and the central bank are working to streamline regulations for such operators.

In Jordan, “Digi#ances” (a CBJ-GIZ implemented project) aims to increase the use of digital financial services, including cross-border remittances via e-wallets, among unbanked Jordanians and refugees, with a specific focus on women.

Cross-border interoperability between payment systems is important, with the Arab Regional Payment System (Buna) aiming to streamline clearing and settlement across Arab currencies.

Blockchain technology holds the promise of offering transparent and immutable ledgers for cross-border transactions.

The use of central bank digital currency (CBDCs) also offers a transformational solution for financial inclusion. A retail CBDC can be stored in a digital wallet on a basic mobile phone (even without access to the internet), allowing unbanked populations in rural areas to receive funds directly and safely.

Superapps are imminent, with remittances just one feature within a broader set of lifestyle and financial services, embedding financial inclusion into users’ daily digital experience.

Nasser Saidi is the president of Nasser Saidi and Associates. He was formerly Lebanon’s economy minister and a vice-governor of the Central Bank of Lebanon.