Dr. Nasser Saidi’s article titled “The case for new green deals in the Gulf” appeared in Aspenia Issue No 89-90, issued in Oct 2020, and is posted below. A PDF file of the article can be downloaded here.

The case for new green deals in the Gulf

The world is in a “new oil normal”, with permanently lower prices. The oil rich countries of the Gulf need to diversify and focus on clean energy alternatives. Europe has a significant role to play here, too, as the EU and the GCC should develop a strategic techno-energy partnership.

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) is weaving its way through two major shocks. Covid-19 and the Great Lockdown resulted in a collapse of oil prices, against a background of climate change and global energy transition. The imf projects an estimated 4.9% decline in global growth this year, with cumulative output losses to the tune of over 12 trillion dollars for the 2020-21 period. Within the GCC, growth is forecast to shrink by 7.1% in 2020, before, optimistically, rebounding by 2.1% next year.

One unintended consequence of the current health crisis has been a record decline in global oil demand, along with emissions reduction and cleaner air as lockdowns were imposed across the globe. I would venture that we are currently in a “new oil normal”, with permanently lower oil prices. It is imperative, therefore, that the GCC’s recovery model include a strong clean energy policy component and structural reforms, alongside a recasting of its economic diversification model and social contracts. The current GCC economic model – over-dependence on fossil fuels, pro-cyclical fiscal policies and generous government subsidies – are unsustainable in the medium to long term.

THE PATH LESS TRAVELLED. As countries enter the second phase of the Covid pandemic of easing restrictions along with social distancing norms, there are two divergent paths for economic activity. One track is that government stimuli, together with lower fossil fuel prices, result in diminished incentives to invest in clean energy and clean tech. This will lead to a business-as-usual mode, to a pre-Covid-19 path. Crises and disasters (sars, 9/11, the 2008 Great Financial Crisis) have been associated with temporary dips in carbon emissions, with a 1.5% decline in output associated with a 1.2% drop in co2. Emissions pick up again, typically with a vengeance, once activity recovers. Recent history provides evidence: it is estimated that following the global financial crisis in 2008-09, carbon emissions increased by 5.9% as a result of policy stimuli.

The second path is a green one wherein countries implement cop21 commitments and energy transition policies, moving to “Green Deals”. This could take multiple forms: we could accelerate the decarbonization of power and road transport, place greater emphasis on energy efficiency investments, phase out subsidies, launch policy incentives to reduce carbon emissions and make a concerted effort to provide no bailouts for industries or business models that are not viable in a low-carbon world. Proactive fiscal policies can help nations become more climate-resilient through investment in climate resilient infrastructure and cities, along with instruments to transfer climate risks to markets (carbon taxes and carbon trading).

According to IRENA’s 2020 “Global Renewables Outlook: Energy Transformation 2050”, decarbonization of the global energy system – away from fossil fuels to renewables – could generate 98 trillion dollars in cumulative growth, adding an extra 2.4% to global gross domestic product. This is a conservative estimate that does not even take into account the negative growth effects of climate change and rising temperatures.[1]

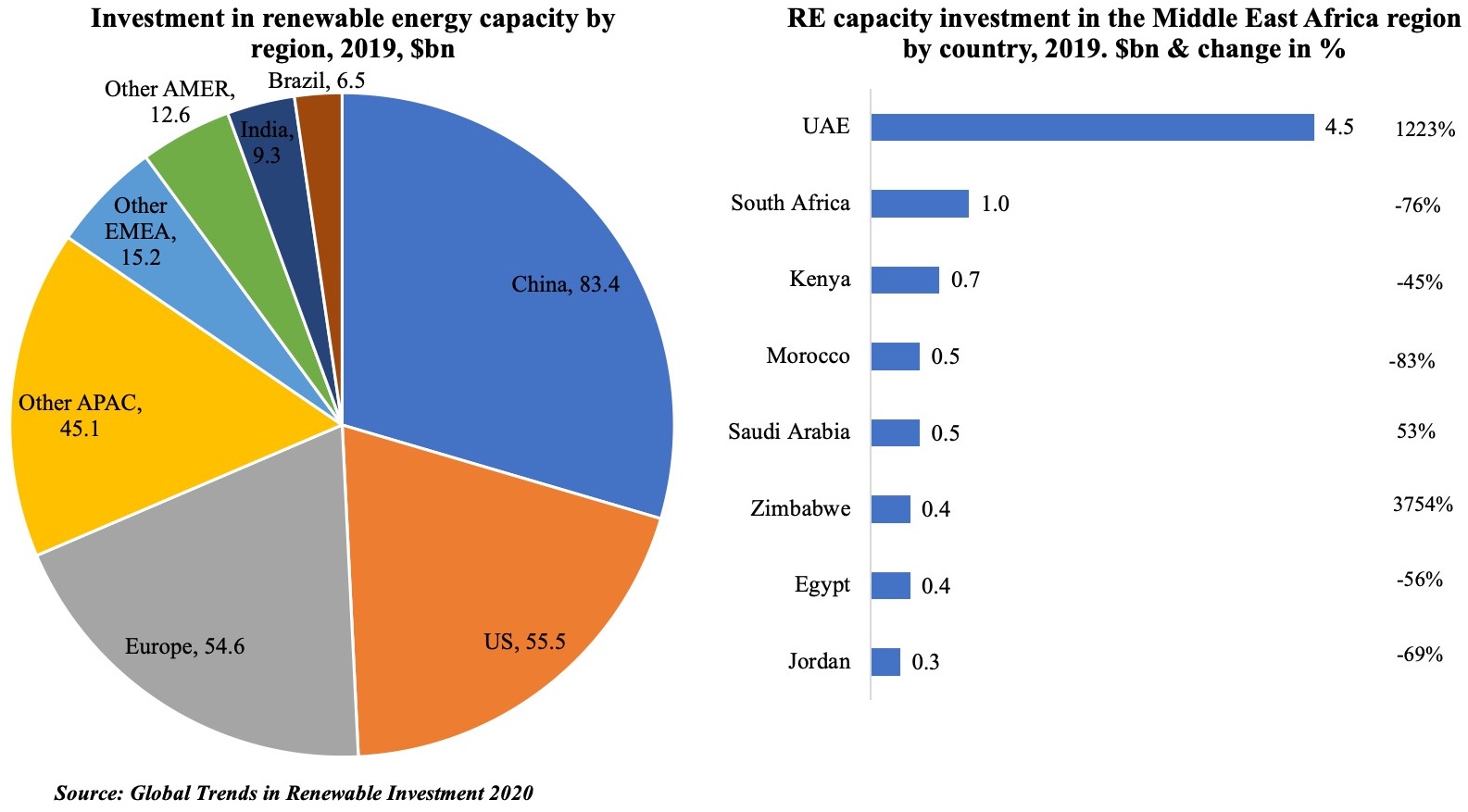

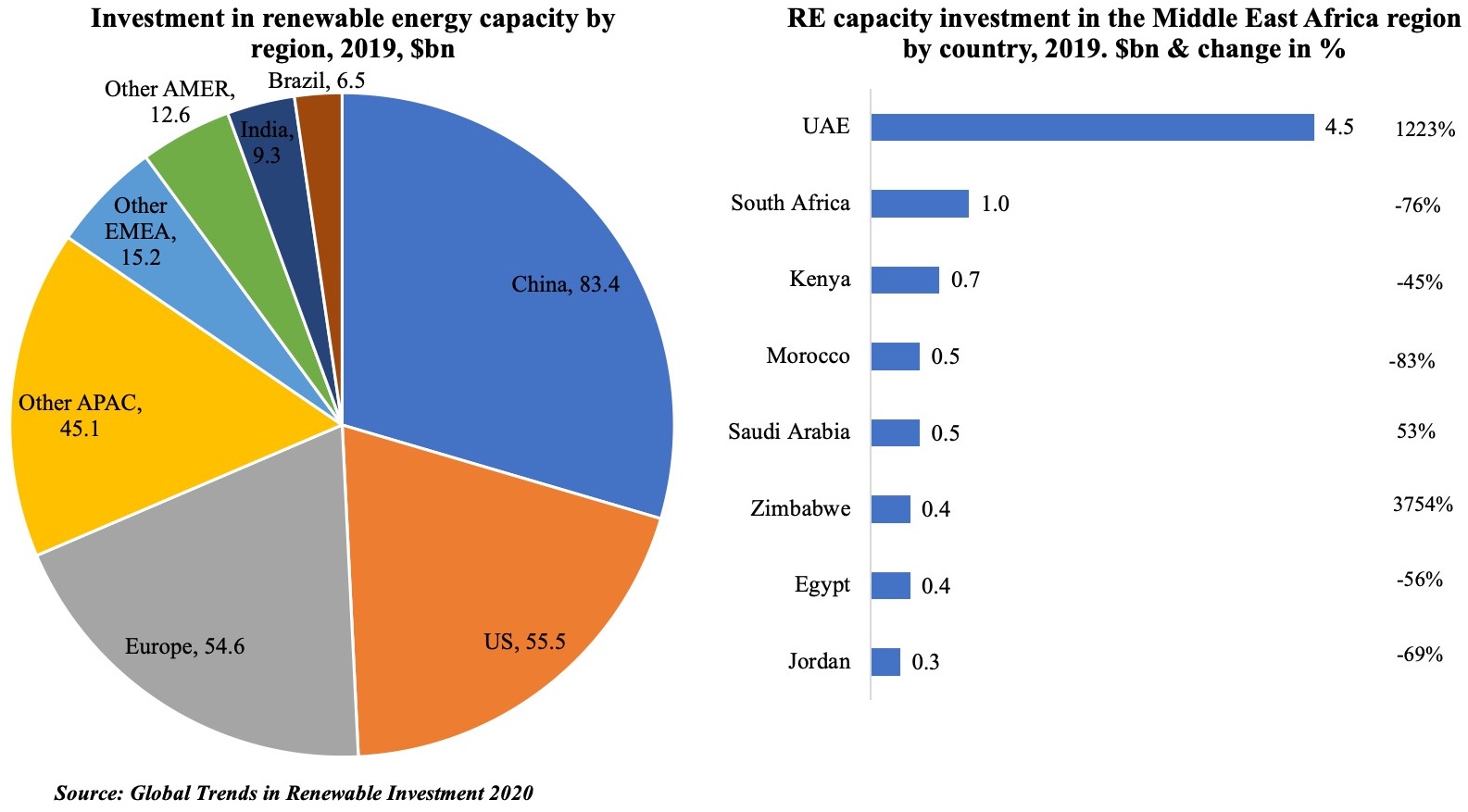

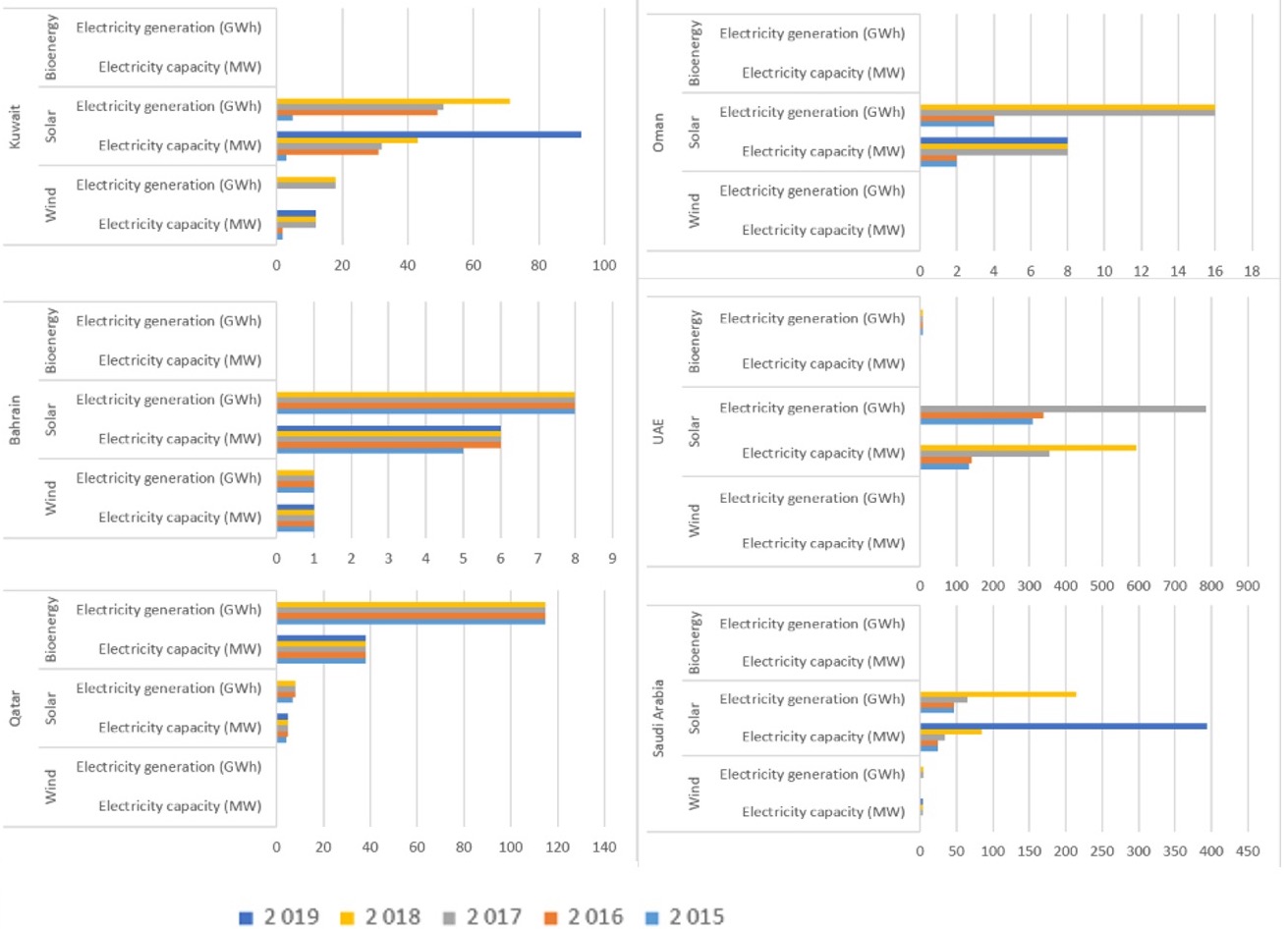

CLEAN ENERGY AND CLEAN TECH INVESTMENTS. Governments in the GCC have been vocal supporters of renewable energy projects despite their vast fossil fuel reserves. The Covid-19 crisis has temporarily slowed deal-making in renewable energies in recent months, and this will likely affect investment levels in 2020. In comparison, renewable energy investments in the wider Middle East and Africa slipped 8% to $15.2 billion in 2019, from a record total of 16.5 billion in 2018.[2] The uae was the biggest investor in renewables in the region last year, with the massive 4.3bn Al Maktoum iv solar project, while Saudi Arabia is accelerating investments, with a total 502 million dollars invested (including a windfarm project). Record-breaking bids in renewable energy auctions in Saudi Arabia and the uae have made solar power cost-competitive with conventional energy technologies. The United Arab Emirates is already ahead of the curve in terms of deployed energy storage to support its grid during high demand hours with two NaS battery storage projects in Abu Dhabi and Dubai.

Figure 1 . Investment: Global vs. Middle East

During the pandemic, governments have reiterated their commitment to support renewable energy policies. Recent announcements – Oman’s financial closure of its Ibri ii plant, uae’s upcoming plans to develop the world’s largest solar power plant (2 gigawatt) in Abu Dhabi’s Al Dhafra region (at a historically low price of 1.35 us cents per kWh), came just hours after Dubai awarded a contract for a project (part of a solar park designed to produce 5 gigawatts by 2030) to generate power at a tariff of 1.7 us cents per kWh, confirm the region’s commitment to the sector.

New renewable energy projects in the region are becoming increasingly reliant on private funding (versus government support previously). Private power developers, who can borrow internationally at historically low interest rates, are helping to lower financing costs thereby leading to even cheaper power. The bottom line is that growing private sector participation in energy projects along with technological innovation that is rapidly lowering the cost of renewable energy production and storage, will accelerate the energy transition in the Arabian Peninsula.

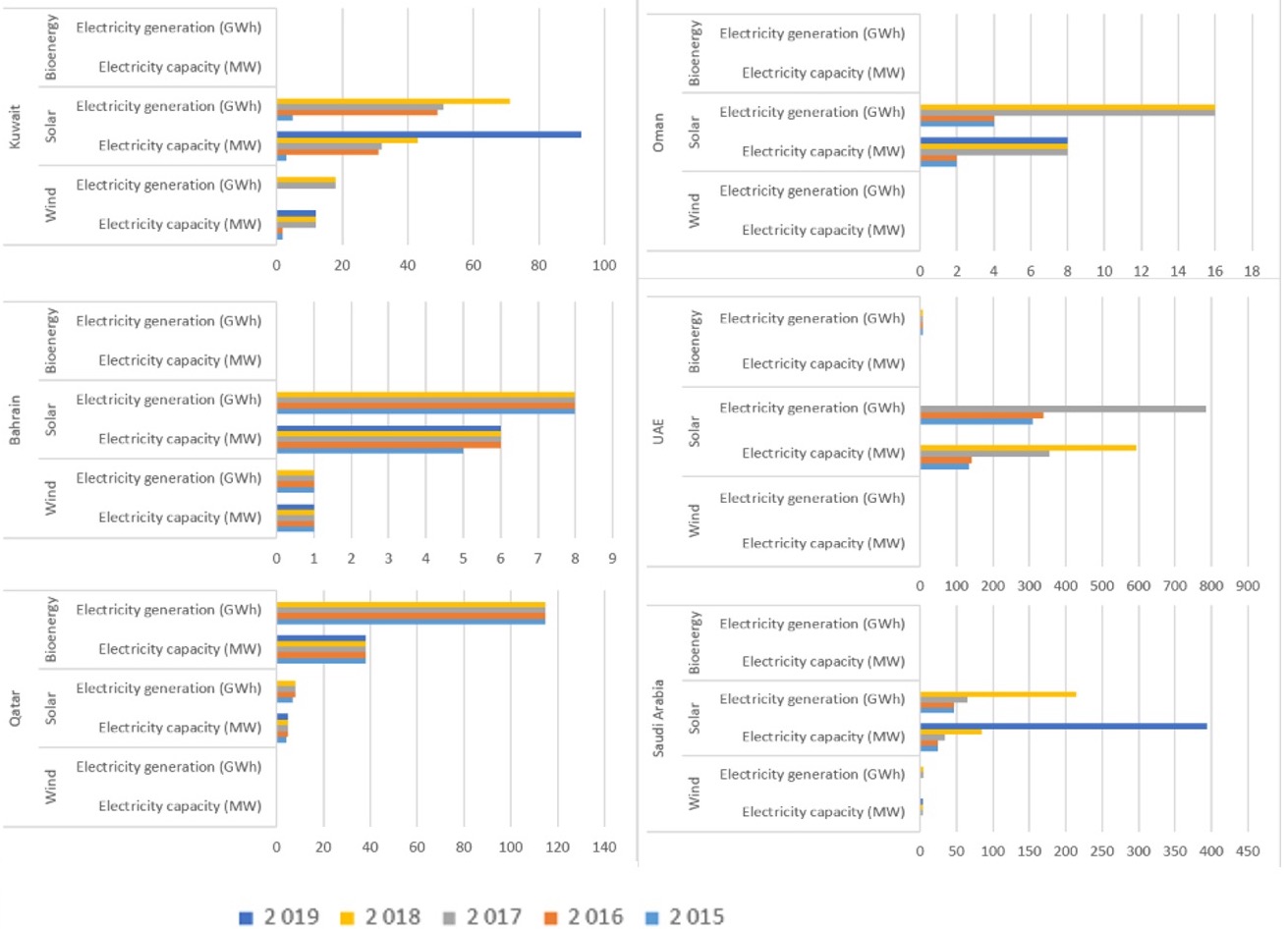

Figure 2 . Electricity generation and capacity in the GCC

Source: IRENA Statistics.

NEW GROWTH MODELS. The new oil normal presages permanently lower real oil prices and the prospect that plentiful fossil fuel (including shale), with increasingly ubiquitous, cheap renewable energy, along with energy transition policy and regulatory measures, will lead to an increasing proportion of fossil fuel reserves becoming stranded assets. This poses an existential threat to the GCC countries, though they are among the world’s low-cost producers. The imf estimates that the GCC’s net financial wealth (estimated at 2 trillion dollars at present) could be depleted by 2034, with non-oil wealth depleting within another decade.[3] The policy imperative for the GCC goes beyond recasting economic diversification strategies that are vulnerable to pandemics, to new development and growth models, with a focus on developing “green deals” as well as “blue deals” (given the vulnerability of GCC coastal areas to climate change). All this, while supporting increased economic digitization too. The current combined crises are a wake-up call for GCC governments to design economic recovery programs to accelerate decarbonization and encourage investment in cost-competitive sustainable technologies. Pre-Covid, there were an estimated 6,722 active infrastructure projects with a combined value of more than 3.1 trillion dollars planned or under way in the GCC. These plans should be radically revised to invest in climate resilient infrastructure covering energy, water, transport and cities. Such a well-planned recovery would cut pollution, reduce the outsized carbon footprint of the GCC and also lead to job creation: each million dollars invested in renewables or energy flexibility is estimated to create at least 25 jobs, while each million invested in efficiency creates about 10 jobs.[4] The added macroeconomic benefit is that the GCC would release oil supply for export rather than subsidize wasteful domestic energy-intensive consumption and production activities.

Figure 3 . Energy transition in the Middle East OPEC nations, 2050

| |

Thousand jobs |

Increment from current plans |

| Renewables |

816 |

169% |

| Solar |

365 |

223% |

| Bioenergy |

139 |

156% |

| Wind |

236 |

259% |

| Energy sector |

3317 |

12% |

| Renewables |

816 |

169% |

| Energy efficiency |

1059 |

11% |

| Energy flexibility & grid |

433 |

17% |

| Fossil fuels |

975 |

-24% |

| Nuclear |

35 |

-35% |

Source: IRENA, “Measuring the socioeconomics of transition: focus on jobs”, February 2020.

BUILDING BLOCKS OF A RECOVERY PROGRAM. I see four major steps to be taken in order to launch a successful recovery in the Middle East.

- Structural reforms. The lowest hanging fruit is the phased elimination of fuel and utilities subsidies that are a drain on government finances. Removing subsidies frees up fiscal resources to provide financial incentives for the ubiquitous use of clean energy and clean technology within the broader framework of a “zero net emissions policy”. Regional cooperation is required to support renewable energy growth across the region through a GCC integrated grid, unification of environmental standards along with a removal of barriers to trade and investment, to benefit from large economies of scale and avoid costly and wasteful duplication. A regional GCC grid could change global power infrastructure by creating an energy corridor to East Africa, to Europe through Egypt and to India and Pakistan through a sea cable. Power exports would compensate the GCC for the gradual secular decline of fossil fuel exports through the export of higher value-added solar power.

- De-risk fossil fuel assets. Across the GCC, state-owned enterprises (soes) and government-related enterprises (gres) are majority owners and operators of upstream and downstream oil & gas (the power sector), while also investing heavily in renewables (even increasing their market share of new capacity relative to private firms in recent years). Given the growing risk of oil & gas reserves becoming stranded assets, the GCC states need to repurpose their soes and gres to support and survive a low-carbon energy transition plan. Saudi Arabia has recently shown the way through the partial privatization of Aramco. The privatization of oil & gas assets should be part of an overall strategy of sharing the risk of potentially stranded assets with investors. Proceeds of the privatization of fossil fuel assets need to be invested in a transformation of the economies of the GCC, sustainable diversification based on partnership with the private sector, with a strategy focused on investing in human capital and sectors capable of competing in increasingly digitized economies.

- Green financing is integral to fuel climate change policies, for a low-carbon transition. Introducing carbon taxes should be the main plank: such taxes would not only raise revenue and increase energy efficiency, they would provide part of the funding for decarbonization strategies. The imf finds that large emitting countries need to introduce a carbon tax that rises quickly to 75 dollars per ton by 2030, consistent with limiting global warming to 2°C or below. For a country like Saudi Arabia, revenues from a carbon tax (35 to 70 dollars per ton of emissions) could raise some 1.9% to 2.7% of gdp in revenue[5] in addition to reducing pollution, and being the most effective tool for meeting domestic emissions mitigation commitments. The other plank for the capital rich GCC is “green finance”. The financial centers of the region could become regional and global centers for new energy financing, for the issuance of “green bonds” and Sukuk, as well as for facilitating the listing of Clean Energy and Clean Tech companies and funds. Ideally, this should be complemented with the creation of Green Banks to finance the private sector. Such institutions would support energy efficiency policies, retrofit where necessary, make climate risk mitigation investments and so on. The imf has estimated an annual financing gap of 2.5 trillion dollars through 2030 to attain the global targets set through the Paris Agreement and the broader un sdgs. Climate finance reached record levels of $360bn in 2019 – but this remains a tiny fraction of the required amount.

- The Covid pandemic has accelerated the digitization process as people, governments and businesses have shifted online. The digitization of the energy sector is next through investments in smart grids, smart city technologies and the deployment of new digital technologies, low-cost cloud computing, the IoT, big data analytics, artificial intelligence and blockchain. This is an unprecedented strategic opportunity for the GCC countries to participate in the Fourth Industrial Revolution through the digitization of their dominant energy sectors, with massive “soft” (including training and building digital human capital) and “hard” investments by industry, prosumers, and governments to increase transform their economies and increase overall productivity growth.

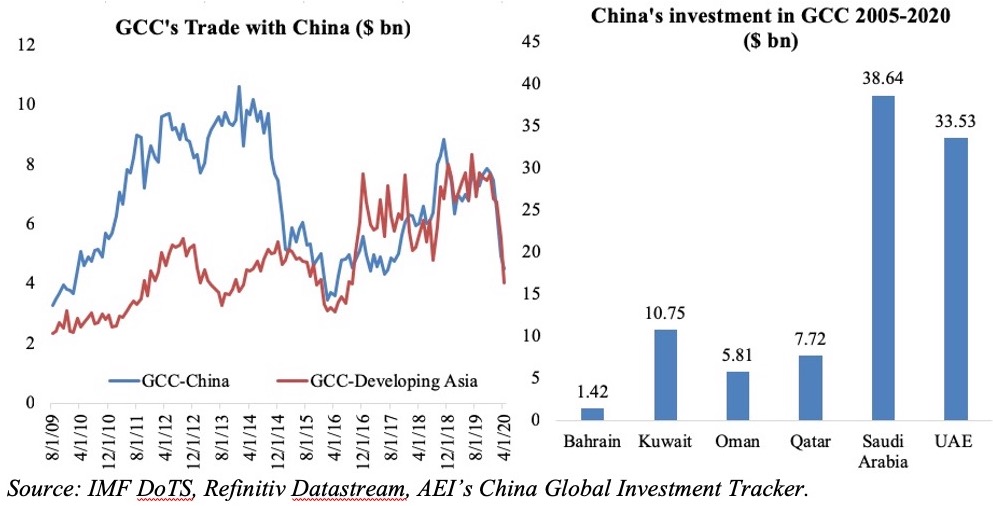

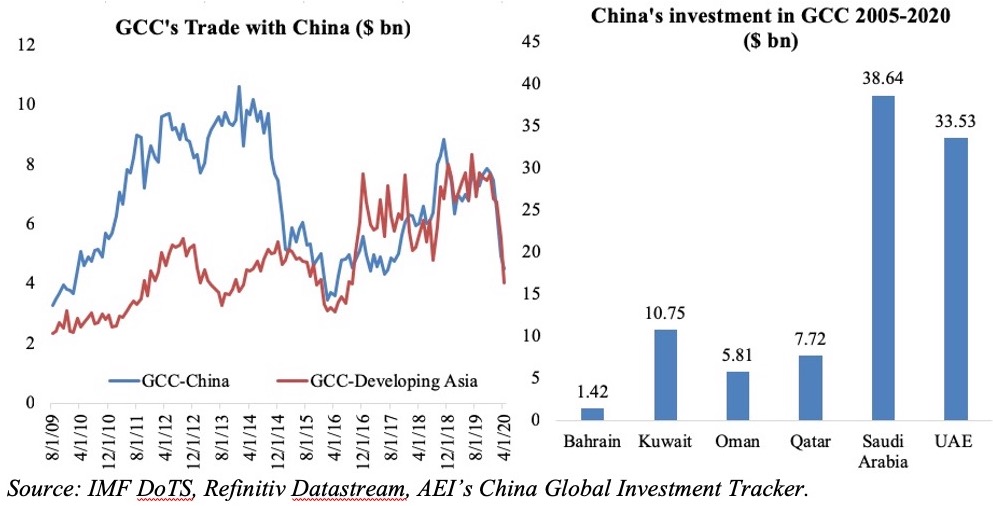

GEOECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES. The year 2020 will likely witness the largest decline in energy investment on record, mostly due to Covid. A reduction of one-fifth – or almost $400 billion – is expected in capital spending compared with 2019.[6] Fossil fuel supply investments (e.g. exploration) have been the hardest hit while utility-scale renewable power has been more resilient, but this crisis has touched every part of the energy sector. As the energy transition progresses in the European Union and the United States becomes a net energy exporter, it implies less energy dependence on GCC. This lessens the region’s geopolitical and geoeconomic importance. How should the GCC react? First of all, greater regional economic integration is required, with a focus on infrastructure and logistics: energy, water, transportation, digital highways. As noted above, a new energy infrastructure would enable the GCC to shift to selling renewable-energy-based electricity to Europe (via an interconnected power grid), to East Africa, but also to Pakistan, India and East Asia. Secondly, the GCC needs to formalize their shifting trade and investment patterns towards Asia and China through new trade and investment agreements with China, Japan, Korea, and the Asean countries. Thirdly, a new extended Gulf security arrangement needs to be negotiated to reduce arms expenditure and focus on economic development. Finally, the EU and the GCC should develop a strategic techno-energy partnership: the Gulf countries could supply solar-generated electricity, while Europe contributes as a renewable energy and climate change technology partner.

Figure 4 . China-GCC trade and investment

[1] Matthew Kahn et al, in their 2019 paper “Long-term macroeconomic effects of climate change: a cross-country analysis”, found that a persistent increase in average global temperature by 0.04 degrees Celsius per year, in the absence of mitigation policies, reduces world real gdp per capita by more than 7% by 2100; abiding by the Paris Agreement limits the temperature increase to 0.01°C per annum, which reduces the loss substantially to about 1%. According to a nasa study, 2010-2019 was the hottest decade ever recorded. A goal of the Paris climate accord was that global temperatures need to be kept from rising more than 1.5°C, but a United Nations report in Nov 2019 found that the world’s emissions would need to shrink by 7.6% each year to meet the most ambitious aims of the Paris climate agreement.

[2] See “Global trends in renewable energy investment 2020”, Frankfurt School-unep Centre, BNEF report, June 2020.

[3] “The future of oil & fiscal sustainability in the GCC region, imf Working Paper, January 2020.

[4] IRENA, “Global renewables outlook: energy transformation 2050, April 2020.

[5] IMF, “Putting a price on pollution”, December 2019.

[6] IEA, “World energy investment 2020”.