Roundtable on Potential IMF Involvement in Lebanon, Lebanese Center for Policy Studies & Jadaliyya, 16 Apr 2020

Reflective of Lebanon’s shortage of foreign capital, the Lebanese government recently announced it will stop payment on all future maturing eurobonds. In parallel, government and financial circles have increasingly discussed the potential need for a package by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to supply the majority of the needed capital. In this roundtable, co-produced by the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies (LCPS) and Jadaliyya, Dr. Nasser Saidi & two other analysts share their views of the amount of capital needed, the potential implications of IMF involvement, and what might need to be different this time around vis-à-vis international borrowing. Dr. Nasser Saidi’s comments are pasted below.

The complete article can be accessed here:

LCPS and Jadaliyya (LCPS&J): How much foreign capital does Lebanon need and for what purpose?

Nasser Saidi: The amount of foreign financing needs to be viewed within a comprehensive, multi-year adjustment and reform program that tackles macroeconomic, fiscal, banking, financial, monetary, and currency sectors of the economy. There are four components to such a program: Macroeconomic and structural reform; banking sector restructuring; public debt restructuring (including central bank debt); and social welfare.

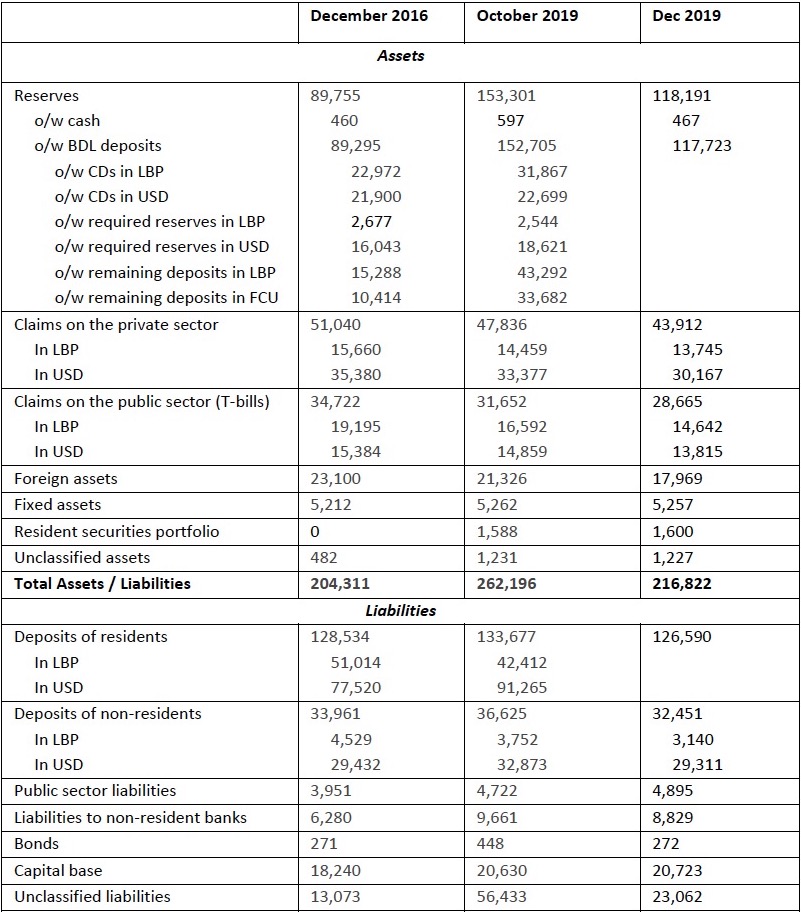

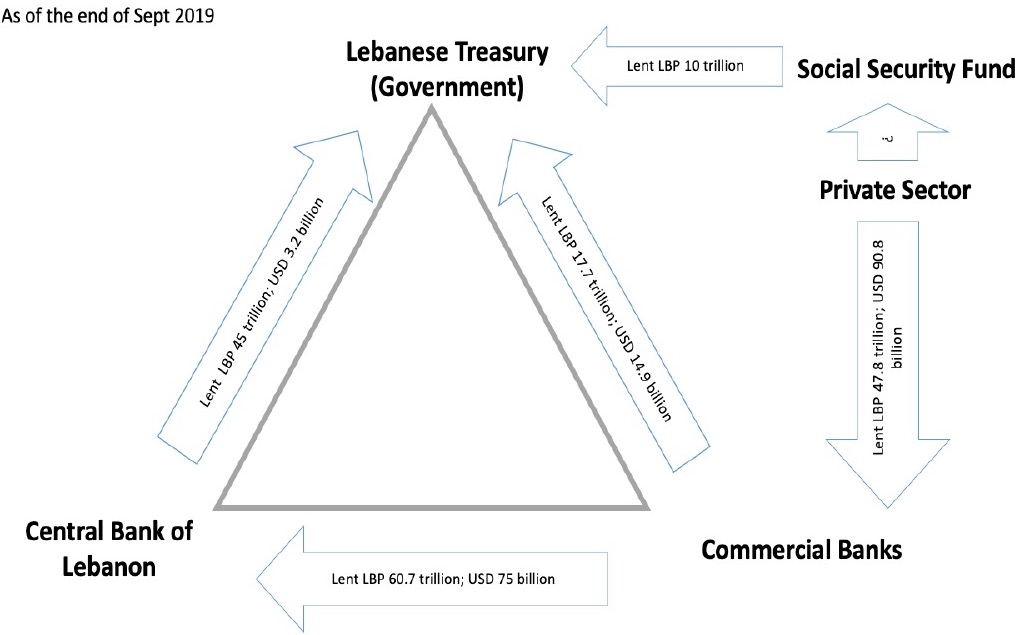

According to government estimates (revealed at a recent presentation to investors) public debt was 178% of GDP at end-2019. The cost of servicing the debt would be just over $10 billion, which is equivalent to approximately 22% of GDP and more than 65% of government revenue. This was an unsustainable position even before the country fell prey to the COVID-19 outbreak. Separately, the central bank (BdL) owes $120 billion to the local banks. BdL foreign exchange holdings have come under high pressure, dropping to about $29 billion in January 2020, of which 22 billion are liquid (18 billion of which is BdL-held mandatory banking sector reserves). It is evident that the banking system needs a comprehensive restructuring.

Given public debt and fiscal unsustainability, the prices of sovereign debt have plummeted by an average of about 50% since the end of 2019. With about 70% of total bank assets invested in sovereign and BdL debt, the write down of debt means that banks’ equity has been wiped out. Bank recapitalization and restructuring will require some $25-$30 billion, of which I estimate some 10 billion would be foreign financing. In addition, a foreign aid package of $25-$30 billion will be needed for macroeconomic and fiscal reform, structural adjustment, central bank restructuring, and balance of payments support, along with the establishment of necessary social safety nets.

This will necessitate an IMF program and multilateral financing. For it, there should be a completely redesigned CEDRE II program. I call it a “Lebanon Stabilization and Liquidity” fund. It is important to note that the overall cost of adjustment and required financing is rising due to unwarranted delay in approaching the IMF for assistance and designing the financing.

Furthermore, the ongoing COVID-19 outbreak is adding more fuel to the fire: We can expect a GDP contraction of 20%, following a 7% dip last year. The government has promised financial aid of 400,000 Lebanese liras (approximately $140, at the parallel market rate of 2,900 liras/dollar) to the most vulnerable families (roughly estimated at 185,000 families combining those registered with the National Poverty Targeting Program, those drivers forced off the job by the lockdown, and frontline healthcare workers). But that will not be sufficient. The sharp drop in economic activity has led to growing layoffs and unemployment, business closures and bankruptcies, and overall falling incomes—all pushing more people into poverty. Social and economic conditions are rapidly deteriorating: Almost half of the population now lives below the poverty line; non-performing loans are likely to increase and many banks could become insolvent; the value of the Lebanese lira is now some 40-50% less on parallel markets fueling inflation; and Human Rights Watch finds evidence of discretionary measures against refugees. The recipe for political and social unrest is boiling.

LCPS&J: What are some of the political and economic implications of securing such capital from the IMF? Could you identify other possible streams of foreign capital that could substitute for an IMF bailout program?

Nasser Saidi: The political and economic implications of an IMF program are all positive, as this would include the development and implementation of a social safety net to shield the more vulnerable segments of the population. IMF program conditionality will force an irresponsible and corrupt political class and its subservient policymakers—who are responsible for Lebanon’s catastrophic demise—to undertake needed reforms (e.g., electricity, fiscal, monetary, and exchange sectors) that should have been undertaken years ago. The policy conditionality would be based on the national program the government should prepare beforehand. An IMF program will add credibility to the reforms included in the proposed Lebanon Stabilization and Liquidity fund.

It is bitter medicine, but the alternative would be lost decades, growing misery and poverty, and the destruction of Lebanon’s economic base. The IMF itself would only be providing part of the funding (some $4-$5 billion) with the balance coming from other international financial institutions (IFIs), the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and the European Investment Bank, and CEDRE participants, including the EU, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, Japan, and China. It is important to note that non-IMF funding will only be available if there is an agreed IMF program. None of the countries and IFIs, including the GCC and EU will provide aid and funding without it. The same is true for private sector investment and finance (e.g., for public-private partnerships), restoration of Lebanon’s access to capital market, or for a sustainable restructuring of Lebanon’s debt. There are no substitutes to an IMF bail-out program and conditionality. Lebanon desperately needs external funding. It cannot rely on purely domestic funding for the restructuring of its public debt and its banking sector (including BdL), investing in infrastructure, reforming public finances and rekindling and supporting the private sector, as well as provide balance of payments support.

LCPS&J: Given the Lebanese government’s poor track record in effectively managing foreign aid, what measures should it take to ensure that such funds are put to meaningful financial recovery?

Nasser Saidi: The government must introduce an anti-corruption and stolen asset recovery program. Transparency International ranks Lebanon 43rd-most corrupt out of total of 180 countries. Protestors have, justifiably, focused on rampant high-level corruption, bribery, and rife nepotism.

The current government must prioritize combating corruption at all levels. This should include: (1) Appointing and empowering a special anti-corruption prosecutor and unit; (2) implementing an anti-corruption program with respect to taxation and revenue collection; (3) reforming government procurement law and procedures; (d) establishing strong and independent regulators in sectors such as banking, financial, telecoms, oil and gas, electricity, among others. And the posts should be filled making sure that the process is completely transparent and that appointees are shielded from political and sectarian influence.

Last, but not least, the state must recover assets that politicians, policymakers, and their associates illicitly and criminally appropriated. Recovering stolen assets can be a wealth-regenerating strategy if implemented properly with complete transparency. Lebanon should immediately participate in The Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative (StAR), a partnership between the World Bank Group and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). StAR works with “developing countries and financial centers to prevent the laundering of the proceeds of corruption and to facilitate more systematic and timely return of stolen assets.”