This article originally appeared in the Carnegie Middle East Centre on 16th Jul 2020. Click to download a PDF of the article.

Click to read the Arabic version of this article.

Lebanon’s Hidden Gold Mine

by Dag Detter & Nasser Saidi

Treating Lebanon’s macro, fiscal & financial ailments alone will not resolve its multiple crises. Better management of the public sector, particularly the handling of public assets, is a critical prerequisite. Establishing a credible National Wealth Fund would help to alleviate the country’s multiple crises.

“One of the tragic illusions that many countries . . . entertain is the notion that politicians and civil servants can successfully perform entrepreneurial functions. It is curious that, in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, the belief persists.” —Goh Keng Swee, former deputy prime minister of Singapore

Since October 2019, Lebanon has been in the throes of an economic and financial meltdown. Unsustainable monetary and fiscal policies and an overvalued fixed exchange rate have led to persistent fiscal and current account deficits. These twin deficits have led to a rapid buildup of debt to finance current spending, with limited public or private real investment.

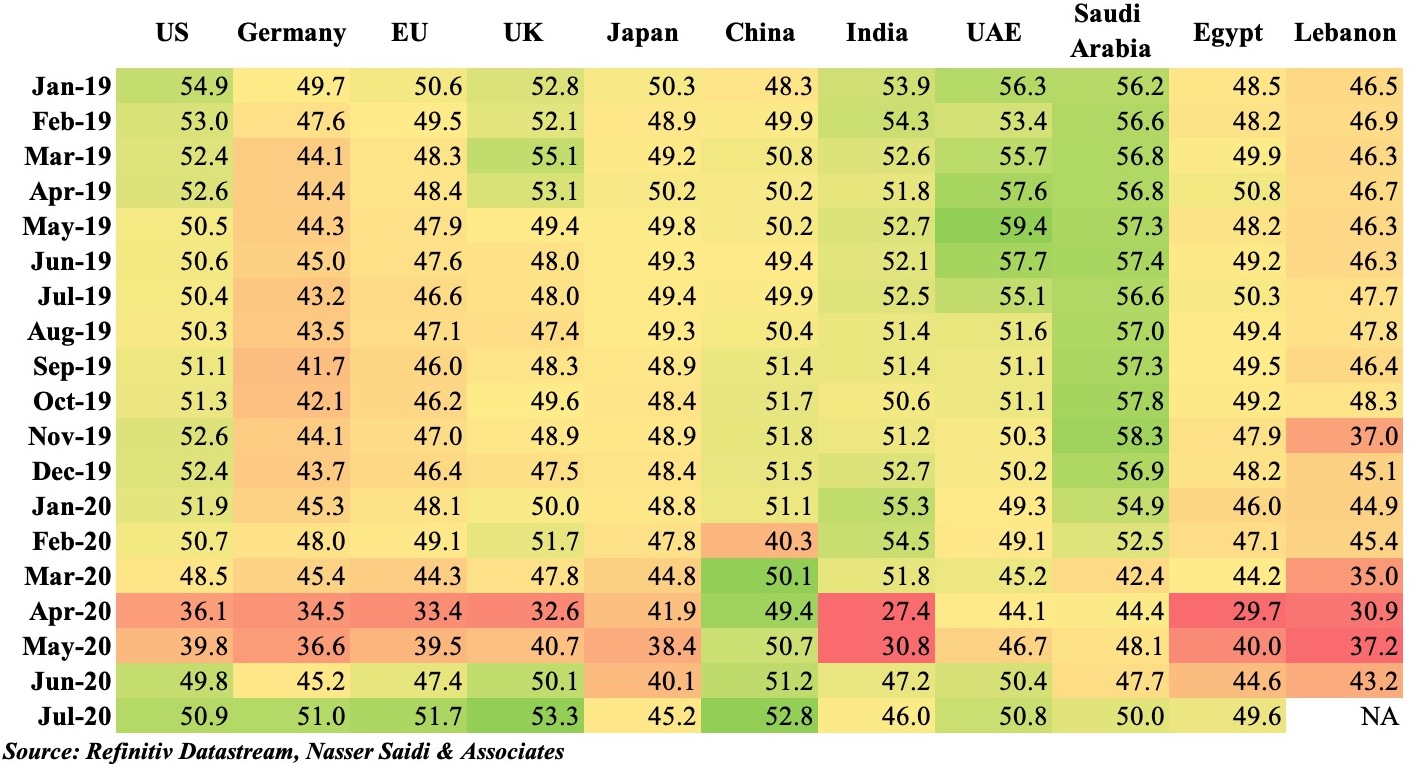

Public debt is projected to reach 184 percent of GDP in 2020—the third-highest ratio in the world. And informal capital controls and payment restrictions to protect the dwindling reserves of Lebanon’s central bank, the Banque du Liban (BDL), are generating a liquidity and credit squeeze and severely curtailing domestic and international trade. This situation has resulted in a loss of confidence in the banking system and the Lebanese pound, as well as a sharp, double-digit contraction in economic growth. Of course, the coronavirus pandemic has only exacerbated these problems.

Lebanon is simultaneously facing a public health crisis, a debt crisis, a banking crisis, and an exchange rate and balance of payments crisis. Together, these crises have created a vicious cycle. The deep recession has led to a steep reduction in government revenues and a rapid increase in the budget deficit financed by the BDL. In turn, the enduring and unsustainable monetization of deficits and debt by the central bank has accelerated inflation, depreciated the pound’s value on the black market, and reduced real income—thereby further depressing consumption, investment, and growth. Layoffs, bankruptcies, and insolvencies, as well as unemployment and poverty rates, are spiking.

Given the economic and monetary dynamics, Lebanon’s prospects are dismal unless a comprehensive reform package is implemented. It must comprise a macroeconomic, fiscal, financial, banking, and structural reform plan that includes restructuring the public debt and fundamentally reforming the public sector. The policy imperative should be credible and sustainable structural reforms with an immediate focus on combating the root causes of Lebanon’s dire predicament—endemic corruption and bad governance.

The government of Prime Minister Hassan Diab has so far prepared a Financial Recovery Plan that comprises fiscal, banking, and growth-enhancing structural reforms. Passed on April 30, 2020, the plan has been presented to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), as part of negotiations for an IMF-funded reform program. But treating the country’s macrofiscal and financial problems without addressing the structural components will not work. Public sector restructuring should be an integral part of the reform process. Fiscal and debt sustainability will not be possible in the absence of a fundamental, systemic overhaul of the government procurement process (a major facilitator of corruption), reform of the pension system and of salaries and benefits for civil and military personnel, and management of the ghost worker problem. The other pressing need is reforming the handling of public assets, an often overlooked part of the public sector balance sheet.

Policymakers and markets characteristically focus on public debt but largely ignore public assets. In most countries, public wealth is larger than public debt. Better management could help resolve debt problems while providing resources for future economic growth. This should be part of any solution for Lebanon.

The Economic Importance of Public Assets

How public wealth is managed is a crucial difference between well-run countries and failed states. Public wealth can be a curse when it tempts political overseers to engage in illicit activities and clientelism. This is exemplified in countries that are endowed with natural resources such as oil and gas but are financially vulnerable because of corruption and bad governance. Public assets in Lebanon are vast, as they are in virtually all countries. In fact, they are a hidden gold mine.

Public assets worldwide are larger than public debt and worth at least twice the global GDP. But unlike listed equity assets, public wealth is unaudited, unsupervised, and often unregulated. Even worse, it is almost entirely unaccounted for. When developing budgets, most governments largely ignore their assets and the value they could generate. Professionally managed public assets could, on average, add another 3 percent of GDP in additional revenues to a government’s budget.

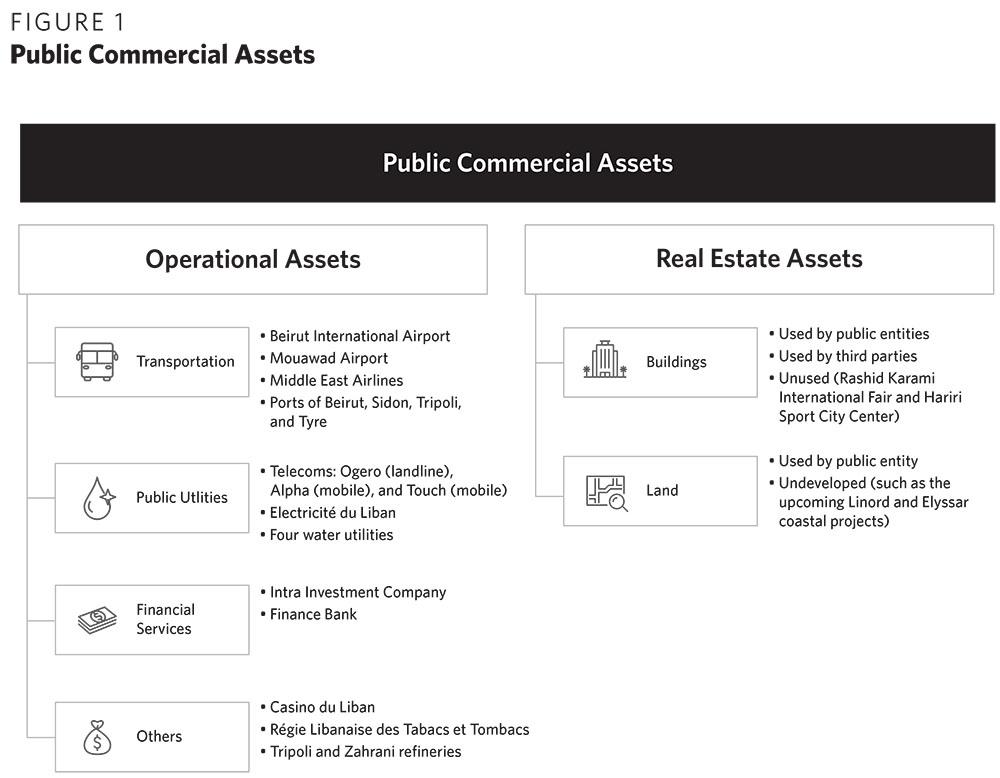

Public assets can be divided into two main types: operational and real estate. In most countries, the value of real estate is often several times that of all other assets combined, with government-owned commercial real estate assets accounting for a significant portion of land. But governments often know about only a fraction of these properties, most of which are not visible in their accounts. This wealth is hidden mainly because public sectors around the world have not adopted modern accounting standards similar to those used by private companies. These standards should be based on accrual accounting, as recommended by the International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board.

Typically, it requires a crisis to bring the issue of public assets to the surface. The political will to address this arises from a recognition that every dollar generated with an increase in yield from public commercial assets is a dollar less gained from budgetary cuts or taxation increases. That is the case today in Lebanon, where a public debate over the management and value of public assets is growing.

Operational assets—airports, ports, utilities, banks, and certain listed corporations—are sometimes called state-owned enterprises (SOEs) when owned by the national government. Although less valuable than real estate assets, these enterprises play a fundamental role in many economies by often operating in sectors on which the economy depends—electricity, water, transportation, and telecommunications. For these reasons, the importance of well-governed SOEs cannot be overstated.

The IMF finds that SOEs tend to underperform. They are on average less productive than private firms by one-third. In Lebanon, poorly performing operational assets are a major factor behind the country’s dismal rankings in the cost of doing business (143 among 190 nations), corruption (137 among 180), and overall infrastructure (89 out of 141).

When properly designed, measures to improve public wealth management can help win a war against corruption. Efficient management of public assets can generate revenues to pay for public services, fund infrastructure investments, and boost government revenues without raising taxes. Such outcomes would simultaneously address two of Lebanon’s greatest problems: the shortage of infrastructure investment due to the public debt overhang and the undermining of democracy through bad governance and through the capture of public assets by politicians and their cronies.

Reforming Lebanon’s Management of Public Assets

The key to unlocking public wealth lies in separating the management of public commercial assets from policymaking and of ownership from regulatory functions. This ensures a level playing field with the private sector and provides a healthy environment for competition. A century of experimenting with public asset management in Asia and Europe has shown that the only effective way of managing public commercial assets is through an independent corporate holding company that is kept at arm’s length from political influence.

Implementing proper governance reforms should aim not only to improve the performance of operational and real estate assets but also to increase the value of the portfolio of assets as a whole. Without generating a relevant balance sheet as part of the budget process, a state’s financial status is unclear—governments focus mainly on debt and cash, without recognizing the existing and potential value of their assets. A financial and fiscal focus on debt and cash alone can lead to bad decisions, such as privatizing an airport to finance infrastructure investment rather than arranging financing against the asset. Recognizing that even a government has a balance sheet consisting of assets and liabilities makes it possible to use net worth (assets minus liabilities) as a fiscal indicator instead of debt to GDP. With a focus on net worth, an increase in debt to finance an investment is matched with an increase in assets. This creates an incentive to invest in government-owned assets rather than to privatize, which is often carried out for the wrong reasons, at the wrong time, and at the wrong price.

A public financial management system that provides better information based on audited accrual data plays a crucial role in facilitating fiscal decision making. Without this information, any level of privatization offers tempting opportunities for quick enrichment through crony capitalism, corruption, or dysfunctional regulation. Privatization should not be undertaken without first also establishing a regulatory framework that includes politically independent competition and the oversight of regulatory authorities. Regulators should be recruited through a competitive, merit-based, and transparent system. Proper regulatory analysis must outline how best to structure market participants and the value chain in order to ensure maximum benefit to consumers, taxpayers, and society.

Empirical evidence internationally shows that waste and corruption can be reduced considerably by improving fiscal transparency and disclosure as well as by ensuring quality procurement systems, expanding digitalization, and reducing the administrative burden. Efficient use of public assets will result in increased overall productivity growth and innovation by encouraging investment and raising private sector productivity growth, thereby contributing to fiscal recovery and stability. Once they are well managed and subject to competition, public assets are ideal for lowering the degree of government ownership—provided that former monopolies are restructured, unbundled, and broken up to help create a fully transparent and competitive environment.

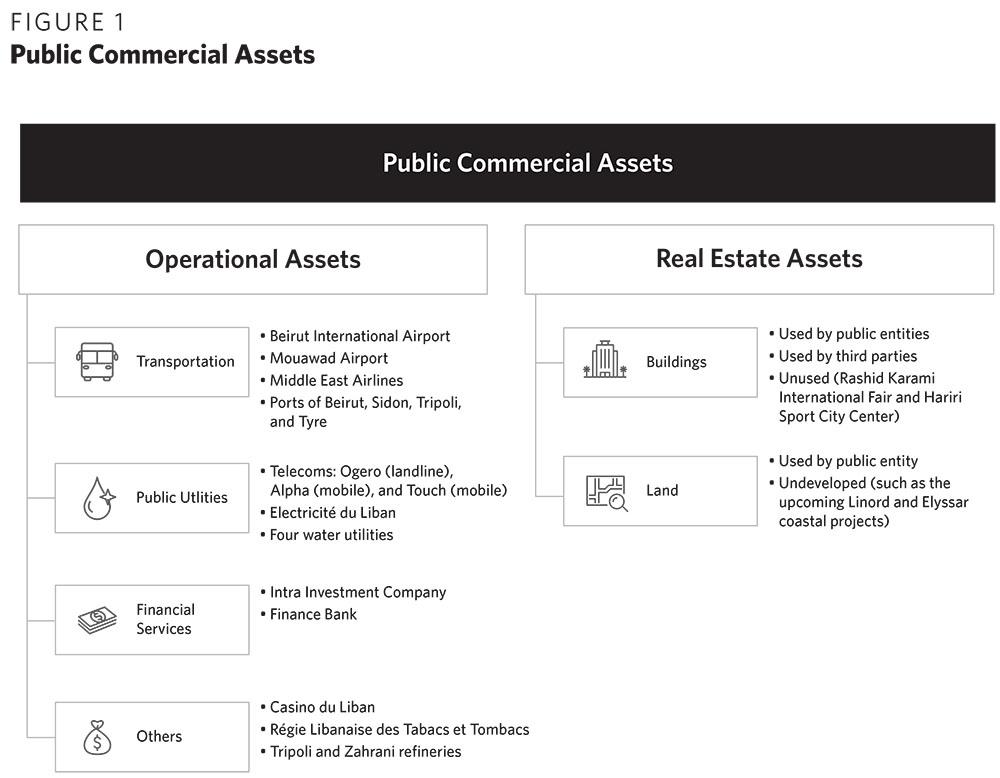

Lebanon’s portfolio of public commercial assets comprises a wide range of operational assets. These include telecoms infrastructure, such as the Ogero fixed network and the Alfa and Touch mobile networks; Electricité du Liban, which is responsible for electricity production and transmission; and four water utilities. The government also owns Middle East Airlines; the Rafiq al-Hariri and Rene Mouawad airports; the Beirut, Sidon, Tripoli, and Tyre ports; the Casino du Liban; the Régie Libanaise des Tabacs et Tombacs; the Intra Investment Company; the Finance Bank; and two refineries in Tripoli and Zahrani (see figure 1).

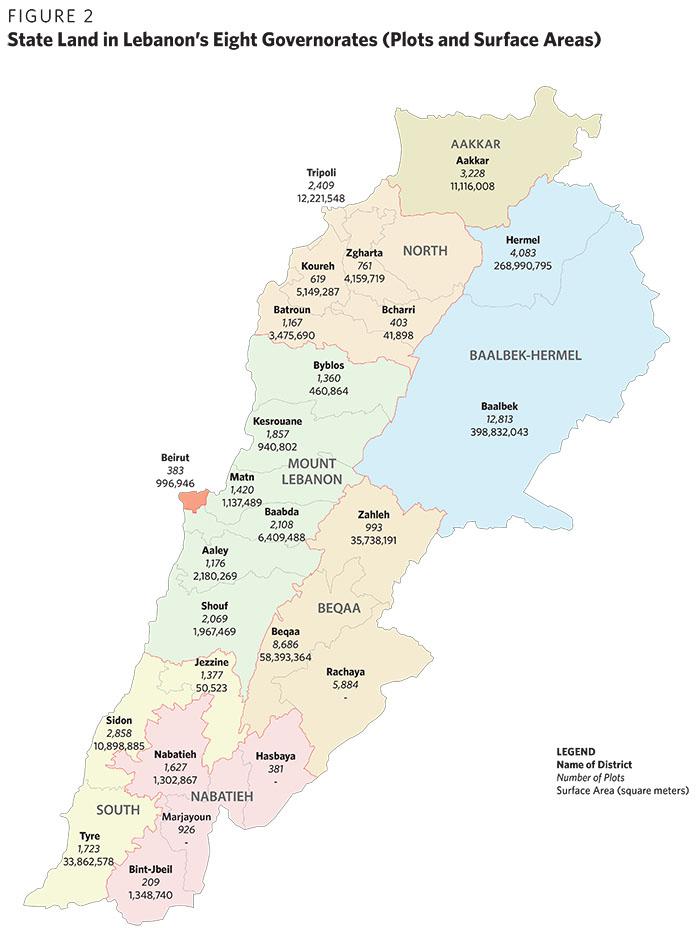

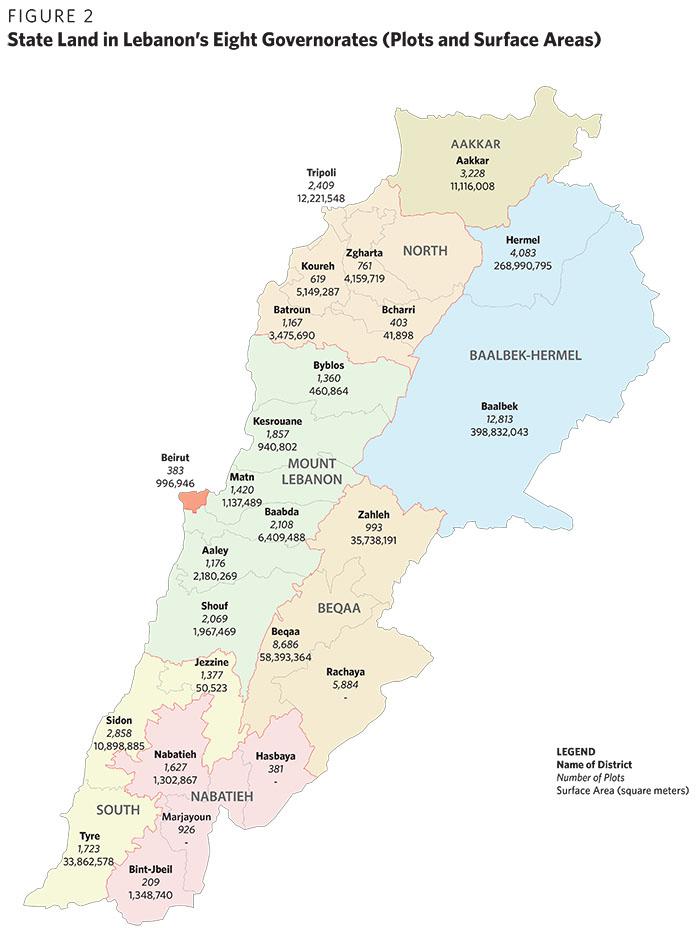

The real estate side of the portfolio is less well understood, due mainly to the absence of an accurate land registry and an official information system identifying relevant data on all geographical objects, including boundaries and ownership. Nevertheless, the government claims ownership of some 60,000 land plots with a total area of more than 860 million square meters (the exact sizes of 30,000 of the total plots are unknown). The land is distributed across Lebanon’s eight governorates, with the highest number of plots and surface areas in Baalbek-Hermel (see figure 2). The majority of plots are less than 1,000 square meters. Due to the lack of proper accounting, there are no valuations of land or buildings—not even of valuable seaside properties captured by politicians, their cronies, and political clients. However, more details are available for property developments such as the Rashid Karami International Fair, the Hariri Sports City Center, and the Linord and Elyssar real estate projects.

Historically, public assets have benefited only a small group of elites, largely due to the influence of politicians. Public assets, ultimately owned by the taxpayers, should benefit the consumers and serve the welfare of all citizens. Without proper transparency, SOEs are allowed to be unproductive and unsustainable, while receiving sizeable government support through budget transfers, subsidized inputs, and cheaper public funding, including loans at below-market rates. Their policies and activities are open to political interference, and as a result, nepotism, cronyism, and clientelism are rife. In addition, weak or nonexistent governance standards, with boards and management dominated by political appointees, have led to corrupt practices, high costs, and inefficiency through overstaffing and unproductive investment.

Political interference and the absence of strong regulatory authorities have resulted in a lack of accountability. In the case of the electricity, telecommunications, and oil and gas sectors, such authorities were established by law but were emasculated by their respective ministries. The lack of transparency and disclosure—with few publicly available, audited, or published accounts—has led to extremely low or negative returns on assets, with operational losses adding to budget deficits. The most visible case is Electricité du Liban, where annual deficits exceed $1–1.5 billion, representing some 30 percent of Lebanon’s budget deficit and 14 percent of overall noninterest spending.

Lebanon’s SOEs are, in fact, nonperforming assets and an integral part of the organized structure of corruption. Problems with inefficiency, low productivity, and lack of innovation have increased costs, lowered private sector productivity, and negatively impacted households more generally. These outcomes have had multiplier effects in the economy by crowding out the private sector and diverting capital and labor to inefficient public assets. Infrastructure quality is a major factor in determining investment and attracting foreign direct investment. The mediocrity of government-provided infrastructure services has reduced domestic and foreign investment, further dampening national productivity and economic growth.

Setting up Lebanon’s National Wealth Fund

The Diab government’s financial recovery plan aims to set up a Public Asset Management Company “tasked with the restructuring of public companies in its portfolio.” However, it does not offer a clear strategy, objectives, or governance mechanism. Is this a prelude to privatization? Will a consolidation of assets without proper governance and regulation enable further abuse by politicians? Meanwhile, the Association of Banks in Lebanon and other analysts have proposed creating a fund that includes public assets. It would serve to repay the central bank’s debts to commercial banks. But this implies giving preferential access to public assets to one set of creditors, namely banks, to the detriment of taxpayers and the public.

That is why Lebanon must establish an independent corporate holding company, such as a National Wealth Fund (NWF), that would own and manage public commercial assets for society’s benefit. The law establishing it would therefore include a fiscal rule stating that any dividend transferred to the government must be used to pay for public services that help alleviate human suffering and rebuild the economy. Monies generated from the better management of the assets, as well as the occasional divestiture or privatization, should first be used to further develop the portfolio so that basic services such as water, electricity, and transportation become more efficient. This to the benefit of the end users, the people, and the economy. In addition, with a commercial capital structure and dividend policy in place, the NWF would be able to produce a yearly dividend to the government—as a complement to revenues from taxes and other measures—to help fund other government requirements.

Professionalizing the management of public assets is a simple two-step process. The first step is to create a central public registry of all commercial public assets (both operational and real estate assets) and assign an indicative value to them. This should be done swiftly to help inform a feasibility study demonstrating what kind of yield and additional revenues could be expected from the NWF. The second step is to transfer these assets into the NWF. The responsibility and accountability of developing the NWF portfolio should be delegated to a professional, experienced, and politically independent board and management team.

With the institutional structure in place, the portfolio should be governed according to the same requirements as any privately owned company and thereby aim for similar returns based on three core principles: transparency, a clear objective, and political insulation. Transparency and disclosure are prerequisites for holding the fund’s board and management team broadly accountable. The NWF should operate according to the highest international norms, as if it is a listed company. Ultimately owned by the taxpayers, it is a truly public company.

Given that the assets in the portfolio are commercial in nature and would be subjected to competition, the NWF’s sole objective should be to maximize the value of the assets by being as financially focused and nimble as a private equity fund. Always aiming to achieve the best possible return would help avoid crowding out private sector initiatives.

Finally, political insulation will be critical for combating corruption and for managing the NWF in a truly commercial manner. That means delegating responsibility and holding the board of directors fully accountable for the day-to-day management of the assets, thereby enhancing the board’s professionalism. Creating an unambiguous separation between the government’s regulatory function and the fund’s ownership of public assets will also improve the likelihood of increased private sector investment and foreign direct investment—as additional ways to enhance and develop the assets in the portfolio.

Furthermore, there is no reason why the board and managers should not be subject to the same legal framework and requirements as private sector owners. In many countries, the functions and responsibilities of boards are clearly defined by law, with government-owned companies having the same accountability as boards in private joint-stock companies. Establishing a level playing field for private and publicly owned companies ensures that they operate under a single legal framework and that managers of public assets can use all the tools of the private sector.

An important advantage of consolidating all state assets under a common corporate structure is the ability to develop an asset to its full potential using the strength of the entire balance sheet of the holding company, instead of being tempted to privatize assets in a fire sale as part of the yearly struggle to close the budget deficit in a political budget process. The timely disposal of assets is instead part of the broader business plan for maximizing yield across the entire portfolio, until the asset has reached a fair value.

The efficient management of assets contributes to higher rates of real GDP growth, generates dividends for the government budget, and lowers operating costs. By making the value of the assets visible to the capital markets and debt holders, the government would improve key financial soundness metrics that the three global rating agencies use in their sovereign rating models. All together, these outcomes help to bolster a country’s governance and institutional strength and, in turn, can improve its sovereign credit rating and lower the cost of borrowing.

Properly managed, the NWF would be able to generate an annual dividend that could help fund socially important functions, ranging from healthcare to infrastructure. This would also ensure that the fund enjoys public support to fight the endemic corruption currently characterizing the management of public assets. Eventually, the NWF would also help reduce the public sector debt load, strengthening the government’s net worth as a buffer against future economic challenges.

Conclusion

Lebanon’s economic and financial meltdown cries for a revolution in policy reform, including the creation of an NWF as part of comprehensive macroeconomic and structural reform. The objectives would be to restructure public assets to combat corruption and inefficiencies, help achieve fiscal sustainability, revive economic growth, and create additional revenues for the benefit of Lebanese society as a whole. Of course, setting up an independent NWF would be a leap of faith and break with the past. The government and the public would need to act together, as a nation, to dismantle the long-standing fragmented political kleptocracy.

About the Authors

Dag Detter is an investment adviser on public assets and the former president of the Swedish government holding company.

Nasser Saidi is a Lebanese economist, former minister of economy and trade and industry, and former vice governor of Lebanon’s central bank.

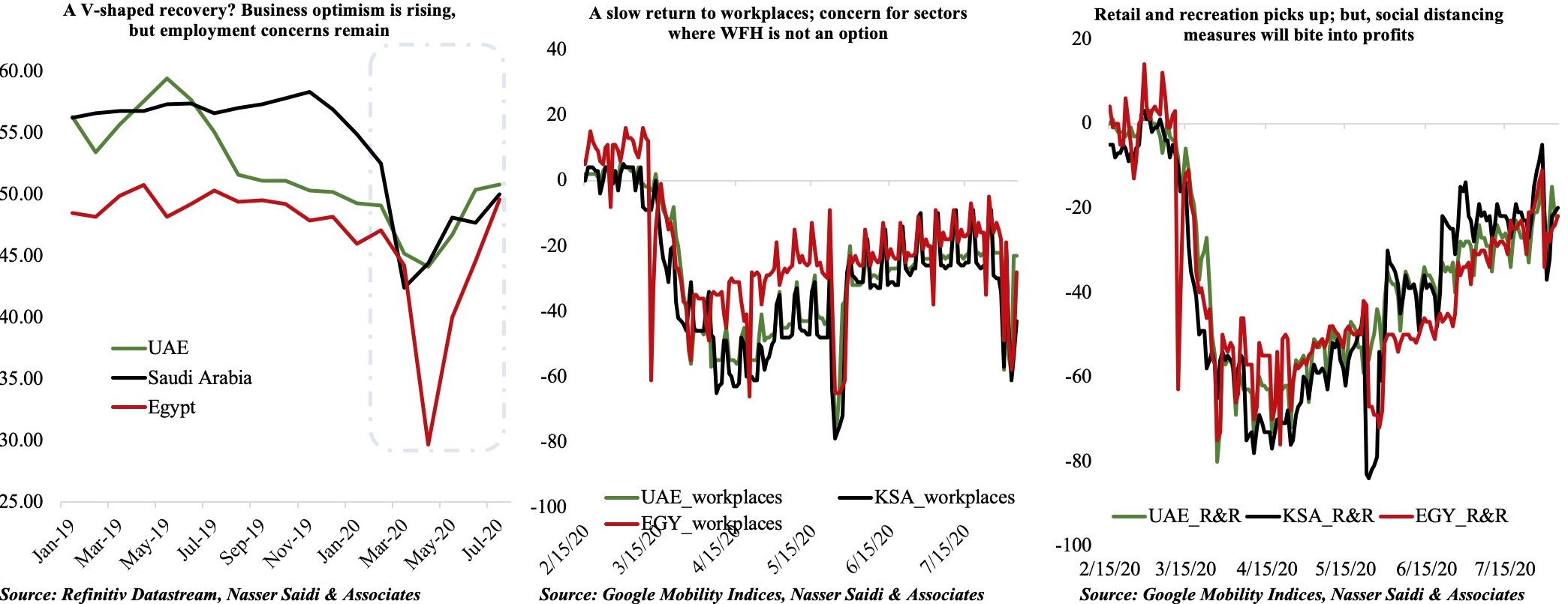

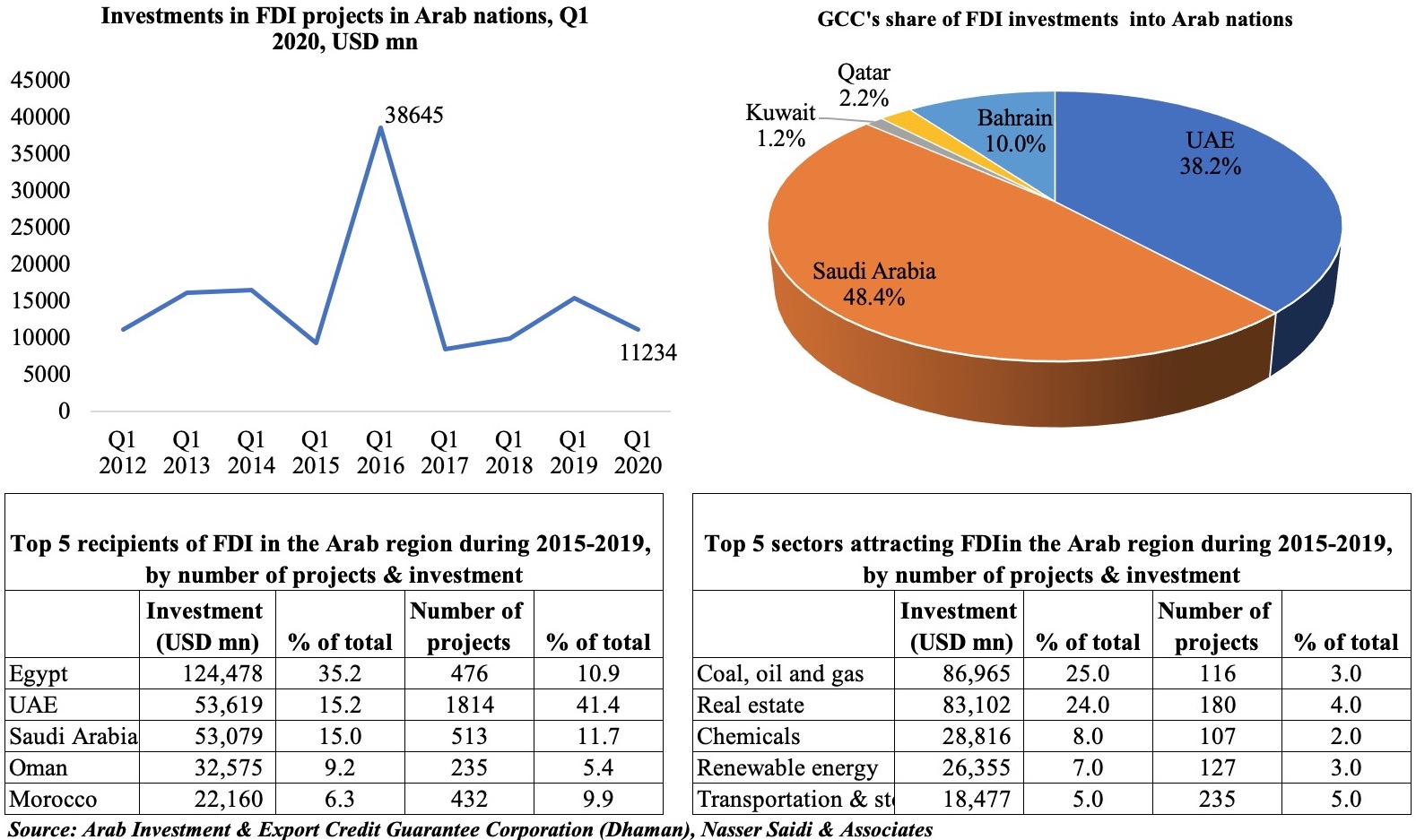

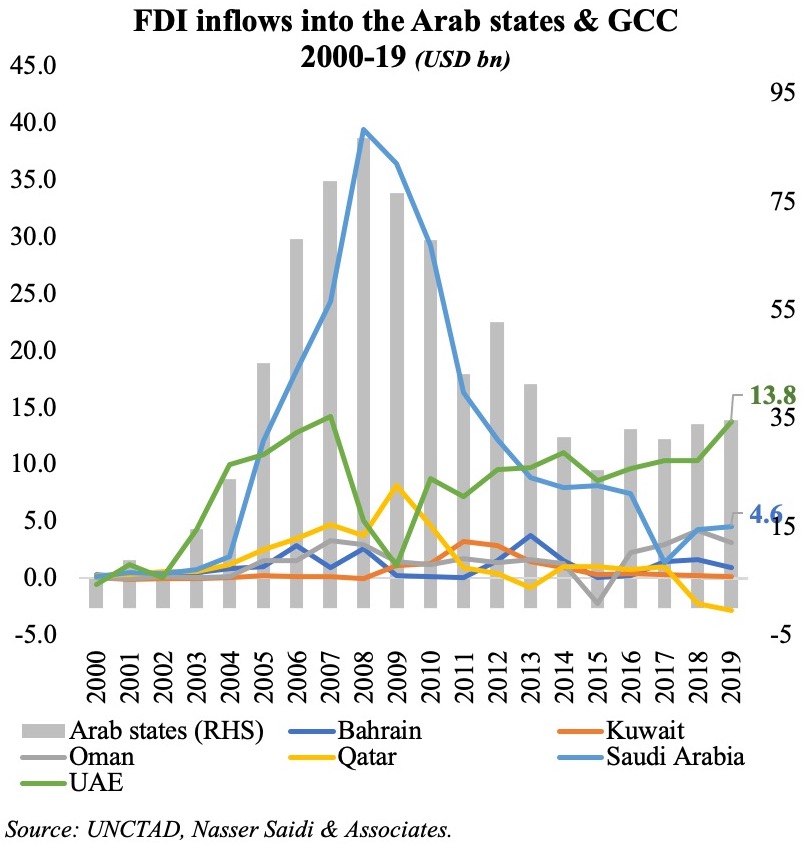

We focus on FDI in this Weekly Insight piece. FDI inflows are essential to the UAE’s diversification efforts, as it would not only create jobs, raise productivity and growth, but could also lead to transfer of technology/ technical know-how and promote competition in the market. According to the IMF, closing FDI gaps in the GCC could raise real non-oil GDP per capita growth by as much as 1 percentage point.

We focus on FDI in this Weekly Insight piece. FDI inflows are essential to the UAE’s diversification efforts, as it would not only create jobs, raise productivity and growth, but could also lead to transfer of technology/ technical know-how and promote competition in the market. According to the IMF, closing FDI gaps in the GCC could raise real non-oil GDP per capita growth by as much as 1 percentage point.

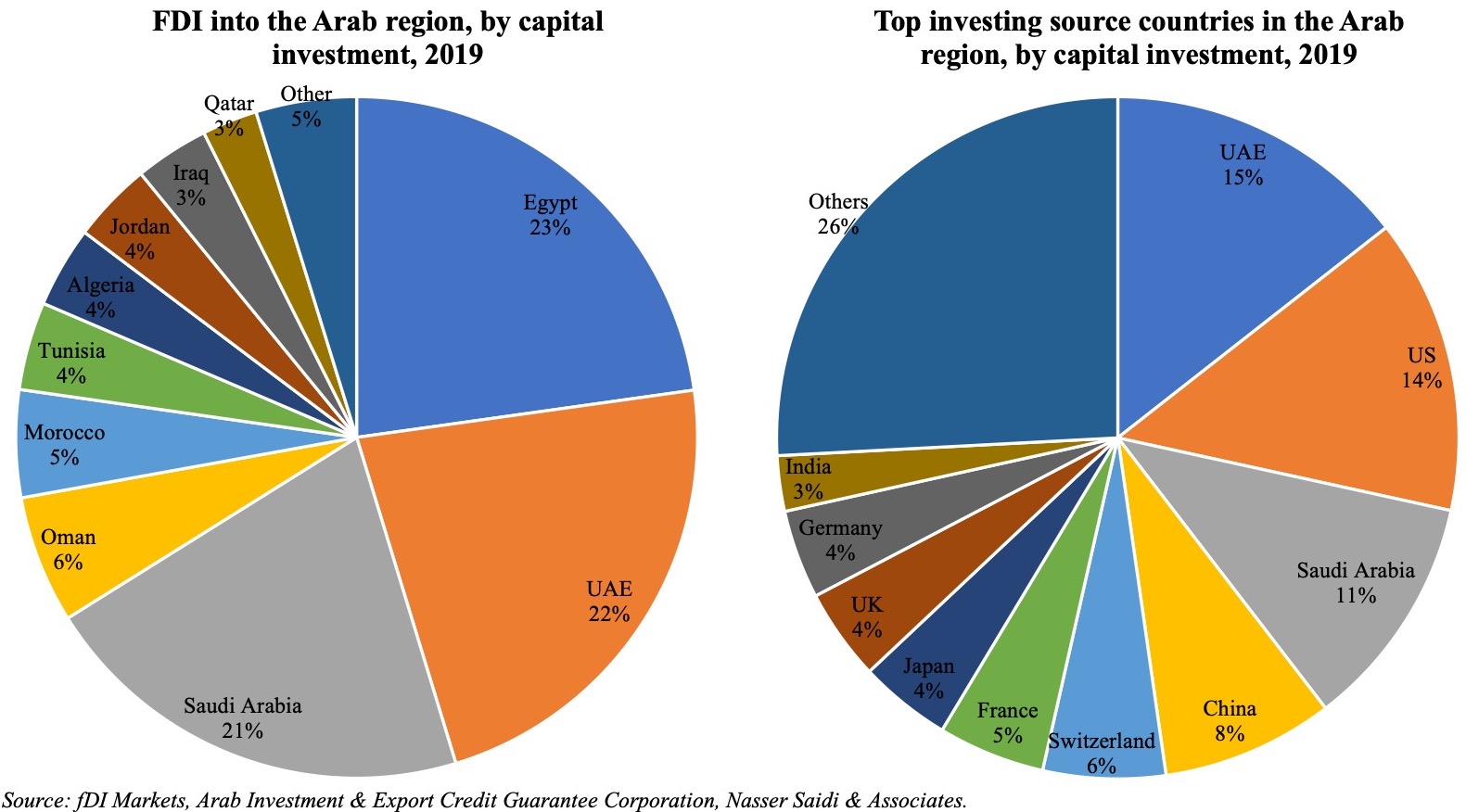

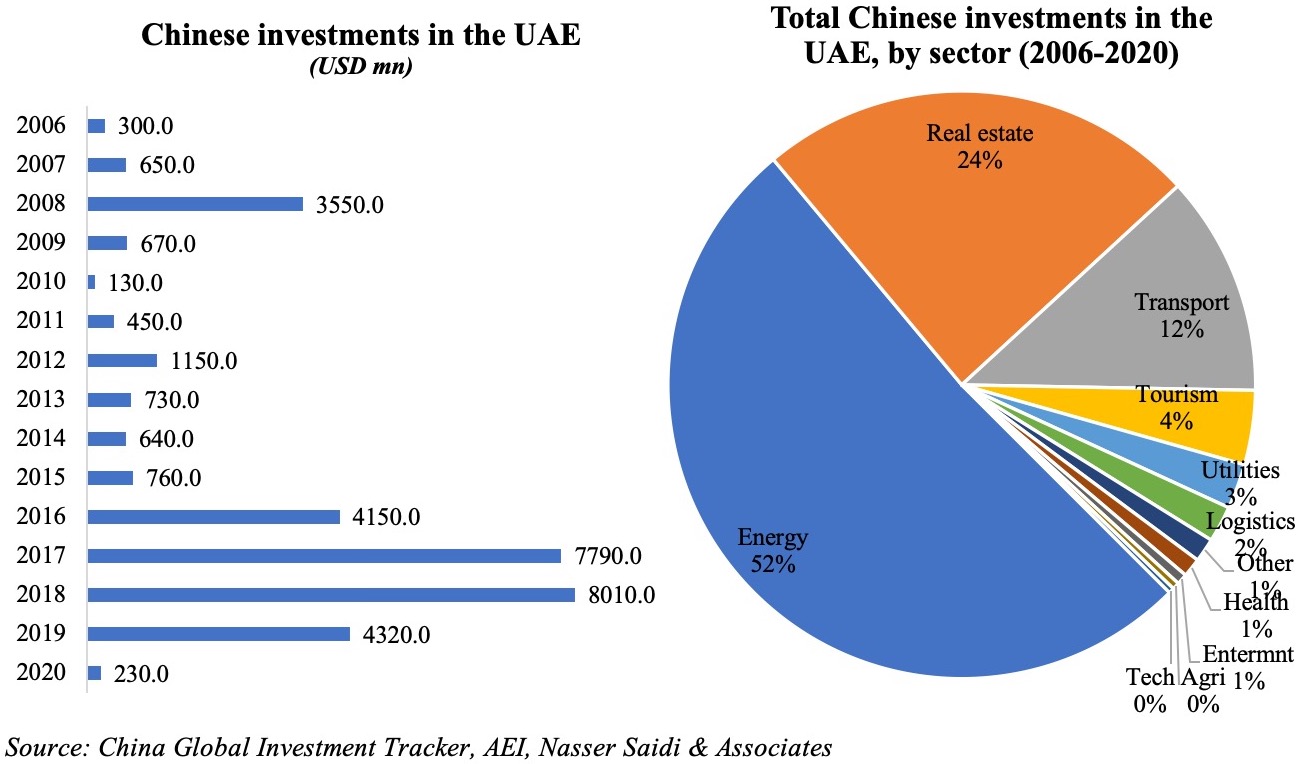

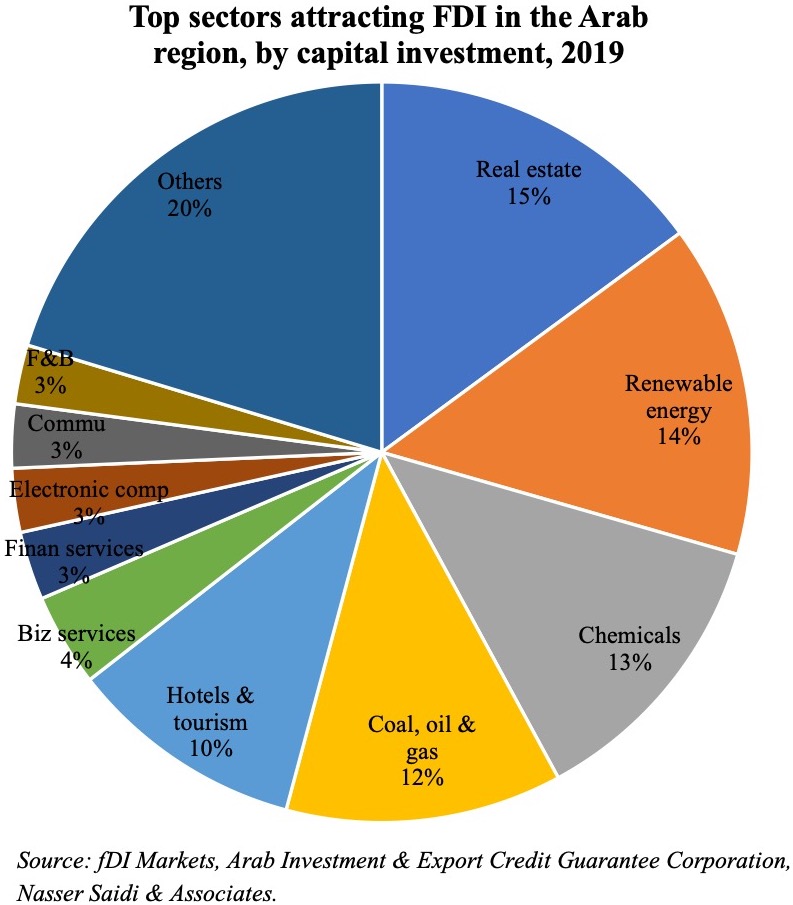

hinese projects tracked during Jan 2003-Mar 2020 (with the number of projects in double-digits in 2018 and 2019). According to AEI’s China Global Investment Tracker, the value of Chinese investments touched a high of USD 8bn in 2018, thanks to a handful of large projects (including with ACWA Power and Abu Dhabi Oil). Sector-wise, investments were concentrated in energy (both oil and gas as well as renewables), real estate and transport – together accounting for 87.8% of total investments during 2016-2020. This is largely in line with FDI inflows into the Arab region as well, with the top 5 sectors (real estate, renewables, chemicals, oil & gas and travel & tourism) accounting for close to two-thirds of total inflows in 2019.

hinese projects tracked during Jan 2003-Mar 2020 (with the number of projects in double-digits in 2018 and 2019). According to AEI’s China Global Investment Tracker, the value of Chinese investments touched a high of USD 8bn in 2018, thanks to a handful of large projects (including with ACWA Power and Abu Dhabi Oil). Sector-wise, investments were concentrated in energy (both oil and gas as well as renewables), real estate and transport – together accounting for 87.8% of total investments during 2016-2020. This is largely in line with FDI inflows into the Arab region as well, with the top 5 sectors (real estate, renewables, chemicals, oil & gas and travel & tourism) accounting for close to two-thirds of total inflows in 2019.