"How knowledge-based human capital can drive UAE’s diversification efforts", Oped in The National, 27 Nov 2020

The article titled “How knowledge-based human capital can drive UAE’s diversification efforts” appeared in the print edition of The National on 27th November 2020 and is posted below.

How knowledge-based human capital can drive UAE’s diversification efforts

Nasser Saidi & Aathira Prasad

Recent structural reforms related to labour will help remove distortions in the market, attracting high-skilled professionals and investment

The UAE recently announced an expansion of its current 10-year golden visa to include medical doctors, scientists and data experts as well as PhD holders, in a bid to attract professionals to the country. The liberalisation comes on the heels of visas for retirees and options for remote working in Dubai: these provide added incentives for expatriates to remain, invest and contribute further to the country’s development.

Currently, an expat’s UAE residential status is linked to an employer, and in the event of job loss, the person has 30 days to either find a new job or secure a new visa. With Covid-19 changing the outlook for jobs globally, these steps come at an opportune time for the country to retain the best talent.

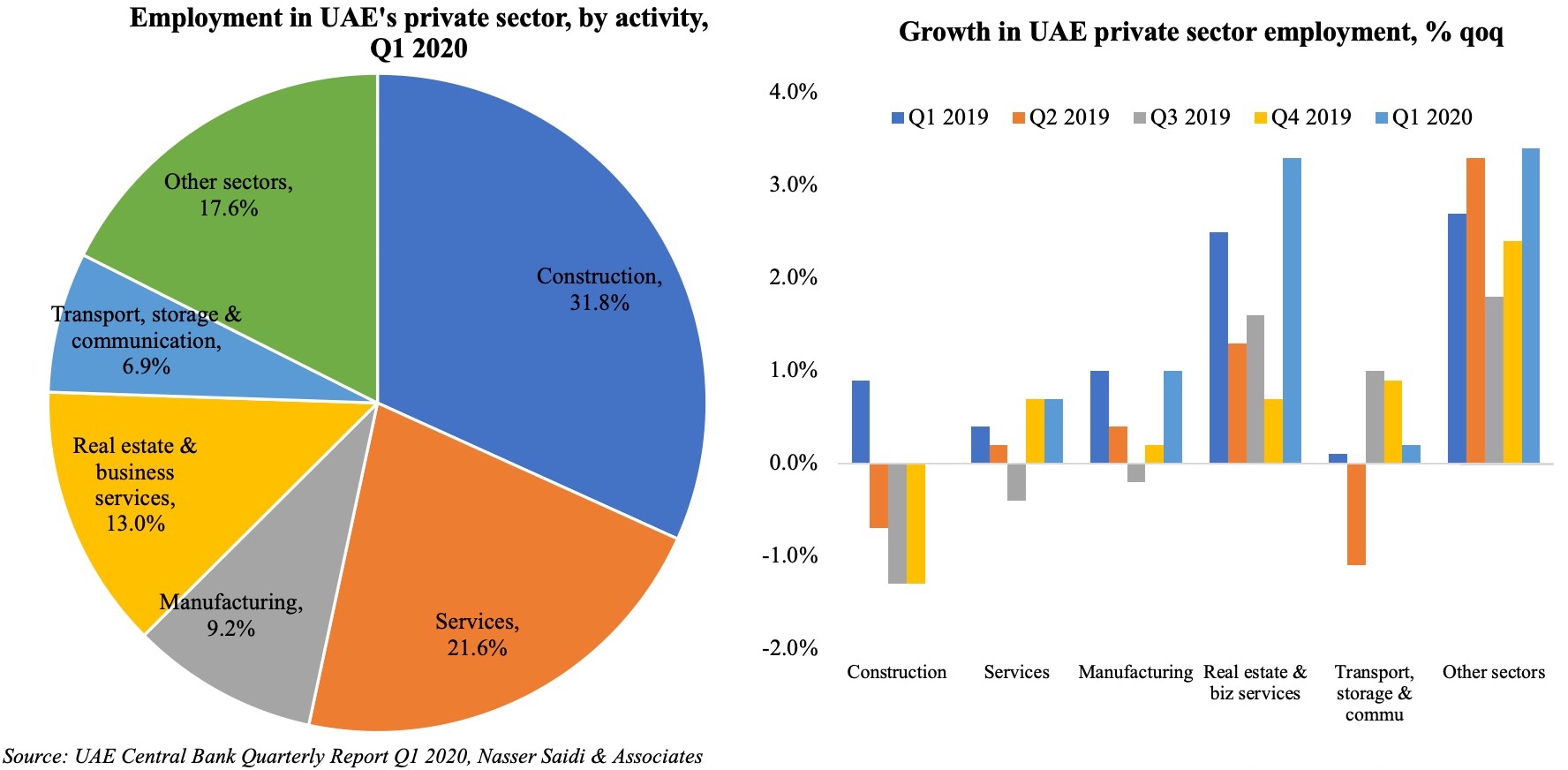

Traditionally, construction and services were the largest sectors offering employment within the UAE’s private sector, according to the UAE central bank’s quarterly report. This data, however, excludes free zone activities. For example, the DIFC is home to 2,584 firms and over 25,000 employees while the DMCC last reported 17,500 member companies in its free zone.

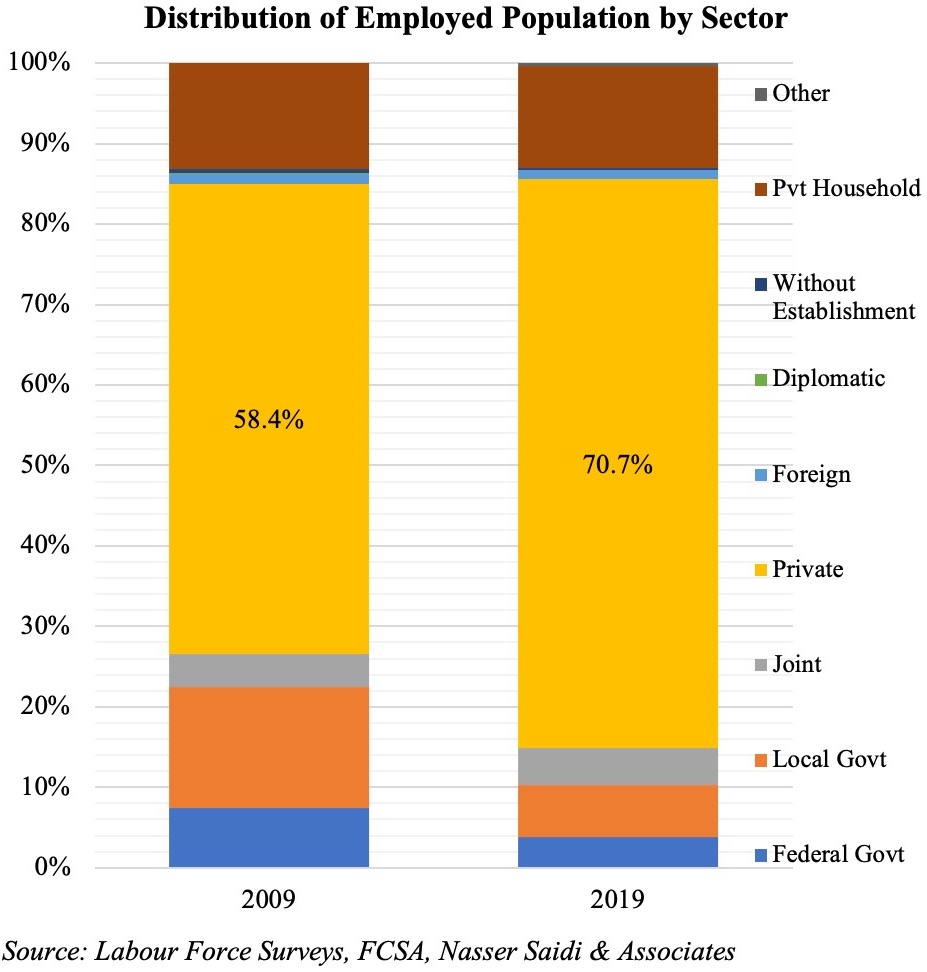

The UAE has also made great strides in increasing the private sector’s participation in the economy as it set sights on greater economic diversification. According to the 2019 Labour Force Survey by the UAE’s Federal Competitiveness and Statistics Authority, the share of the private sector in the UAE has increased to 70 per cent in 2019 from 58 per cent in 2009 – a positive move that underscores diversification efforts.

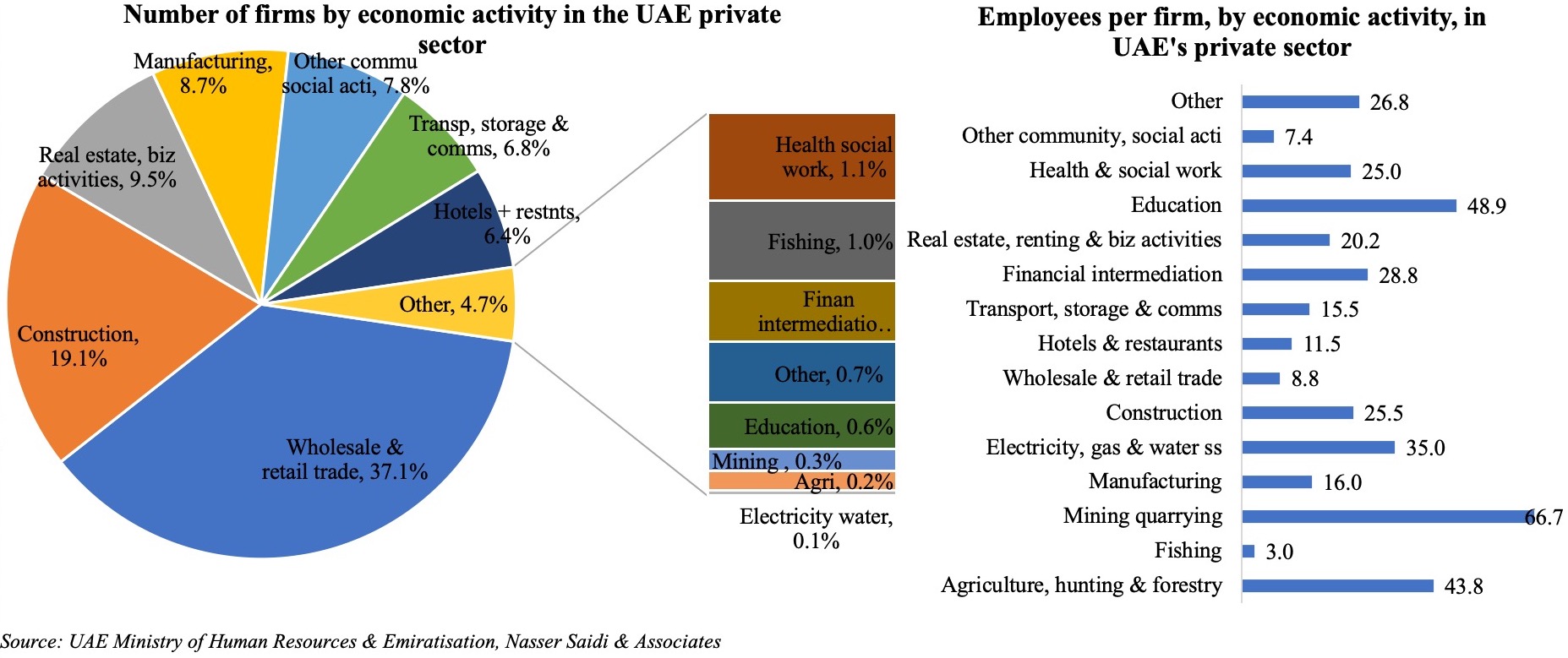

By economic activity, a few sectors have seen an increase in their share: manufacturing (9.2 per cent in 2019 vs 7.7 per cent in 2009), construction (17.5 per cent vs 12.3 per cent), hotels and restaurants (5.4 per cent vs 4 per cent). The real estate sector has seen a significant drop during the decade, which is not surprising given the boom prior to 2010.

Another interesting insight from the Labour Force Survey offers a morale booster for women – women are relatively are more educated than their male counterparts (about 50 per cent of employed Emirati women have a bachelor’s degree while 10 per cent have a bachelor’s and above). The comparable numbers for expat women are at 42.8 per cent and 33 per cent, respectively. A high proportion of women work as professionals and managers as well. This shows that though women are transforming the labour force they still face a glass ceiling. It is time that we have more women on boards and at top management levels in the private sector.

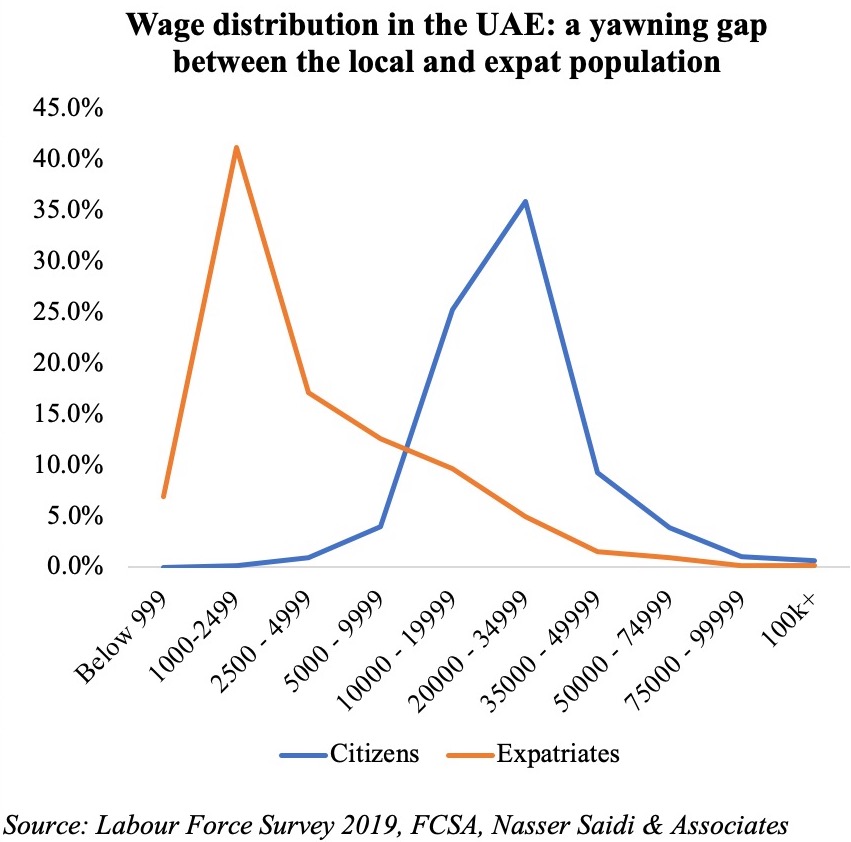

The survey also showed that the public sector, with better salaries and benefits, continued to outweigh the private sector in terms of appeal. Though wages by sector breakdown is not available (publicly), it is safe to assume the government sector has relatively higher salaries where close to three-quarters of citizens work. According to the UAE’s Labour Force Survey, more than one-third of Emirati respondents disclosed receiving monthly wages between Dh20,000 to 35,000 (versus just 5 per cent of expats in the same income bracket).

But for long-term growth and to further increase the private sector’s contribution to GDP, it is important to increase the proportion of UAE nationals in privately-held firms.

While attracting foreign talent to take up such jobs in the near-to-medium term is necessary, it is also critical to reform the education sector and invest in building a knowledge economy.

There is a persistent skill mismatch in the country compared to market requirements. Though spending per capita is high and student-teacher ratios are comparable to OECD levels, the outcomes are not strong: the PISA 2018 scores, for example, reveal that UAE students are placed 50th in maths, 49th in science and 46th in reading. It is time to invest in curricula that support job readiness, ‘Digital Education-for-Digital Employment’, early exposure to the workplace (summer internships and labour policies that facilitate such changes, for example), vocational and on-the-job training. Increasingly, emphasis should be to invest in and promote STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) – especially given the official policy focus on innovation and a shift to the digital economy in the UAE and the region.

The recent structural reform related to labour will help remove distortions in the market, attract high-skilled professionals and help the UAE diversify further while also supporting domestic investment (including in the real estate sector). This will happen in tandem with a reduction in outflow of remittances, which in turn will boost the balance of payments. Last year, outward remittance flows from the UAE reached $44.9bn.

Long-term residents will be keen to invest in medium- and long-term financial instruments, secure mortgages and invest in start-ups and growth companies.

The Survey also confirms the disparity in wages between local and expat population: more than one-third of Emirati respondents disclosed receiving monthly wages between AED 20-35k (versus just 5% of expats in the same income bracket). This brings to the forefront two issues:

The Survey also confirms the disparity in wages between local and expat population: more than one-third of Emirati respondents disclosed receiving monthly wages between AED 20-35k (versus just 5% of expats in the same income bracket). This brings to the forefront two issues: