The opinion piece titled “Markets face bumpy ride rather than soft landing” appeared in the Arabian Gulf Business Insight (AGBI) on 29th January 2024.

The article is published below.

Markets face bumpy ride rather than soft landing

Persistent inflation, high interest rates and slow growth will dog 2024

Inflation surged post-Covid, reaching multi-decade highs of 8.7 percent in 2022 globally, driven by pent-up consumer demand, supply disruptions, the Russia-Ukraine war and ultra-easy monetary policy.

But a less commented-on major cause of inflation has been fiscal profligacy.

Governments boosted spending, increased subsidies, provided business incentives and reduced taxes to revive consumption and maintain jobs, all financed by public borrowing encouraged by historically low interest rates and central banks’ quantitative easing.

The result was a surge in budget deficits and public debt rising to the highest levels since the end of the World War II.

The world also experienced its largest debt surge since World War II during 2020. Global debt rose to $226 trillion (or 256 percent of GDP) with public debt accounting for about 40 percent of the total.

The global public debt ratio soared to a record 99 percent of GDP in 2020. The IMF forecasts global government debt to touch $97.1 trillion in 2023 (a 40 percent increase since 2019), with the US accounting for over one-third of total public debt ($33.2 trillion, or 123.3 percent of GDP).

According to the Congressional Budget Office, net interest will total more than $13 trillion over the decade through 2033, exceeding defence spending by 2025 and the net cost of Medicare by 2026.

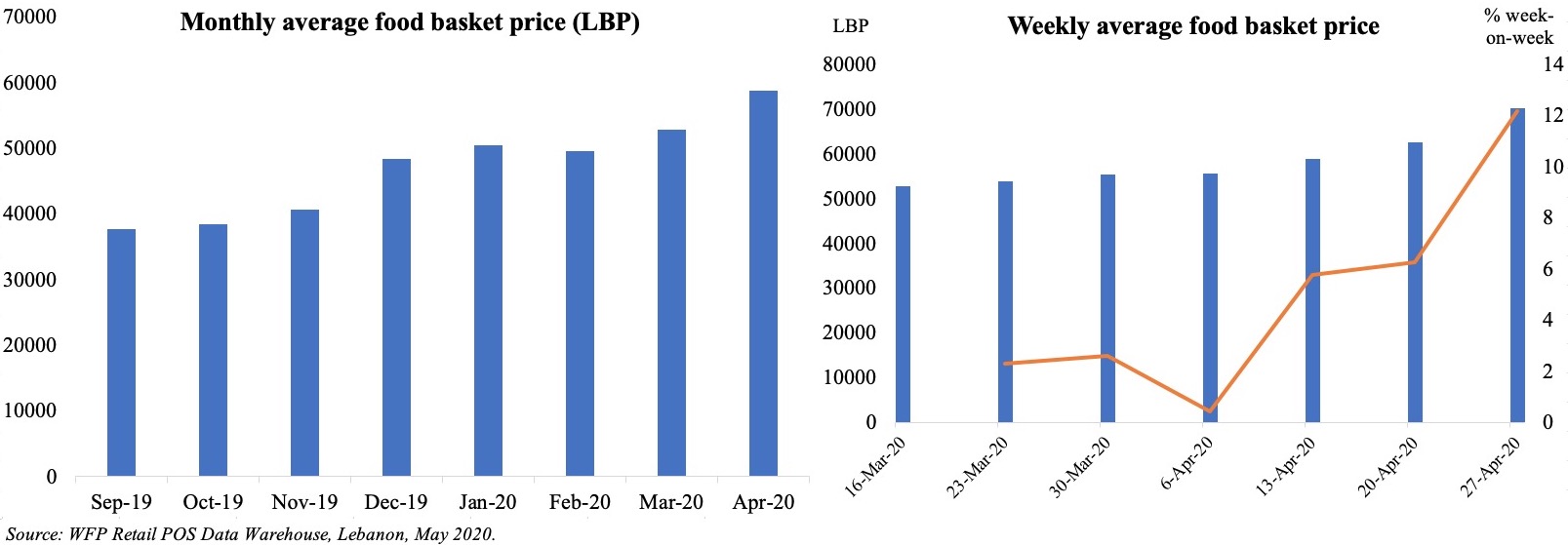

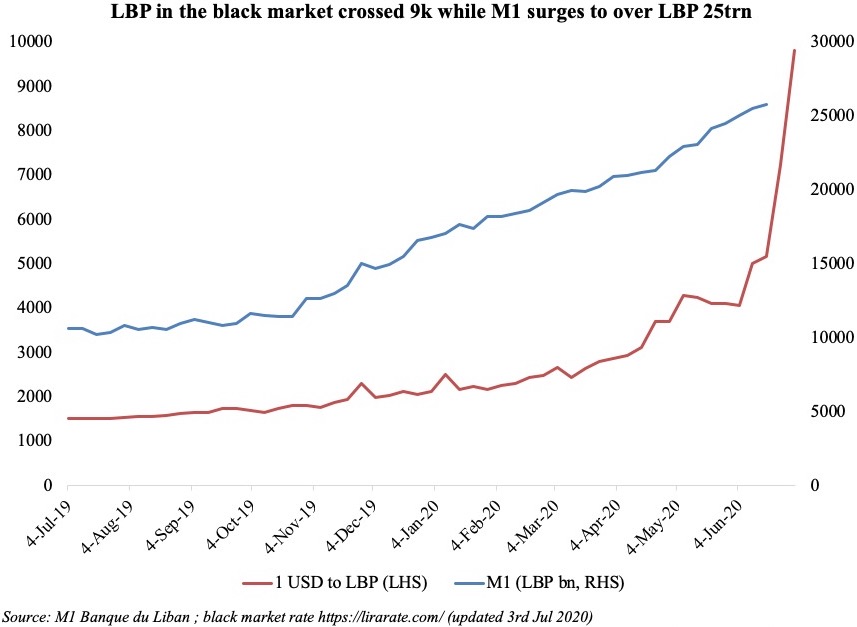

In the Middle East, Bahrain’s debt to GDP is running at 121 percent, while Egypt is expected to see around 40 percent of revenues going towards debt repayments. Lebanon has been in default since 2020.

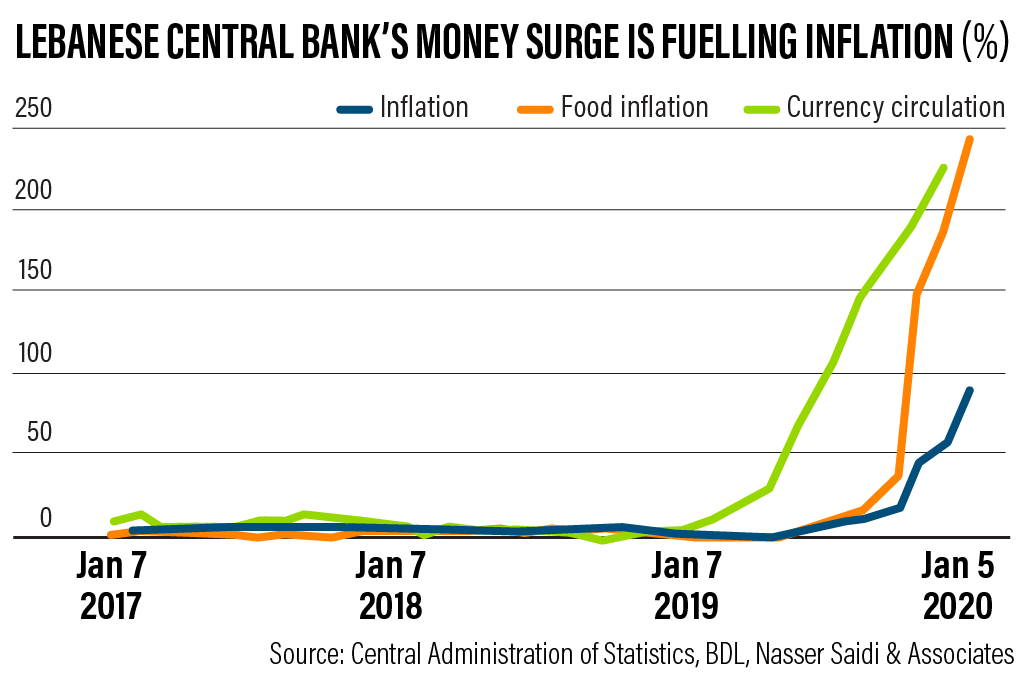

Governments and central banks underestimated the inflationary impact of a doubled-barrelled bazooka of increased deficit spending, with low rates and quantitative easing. From 2009 until the end of 2022, net asset purchases by major central banks (the Fed, ECB, BoE and BoJ) totalled about $20 trillion.

Central banks have since reversed course and applied the monetary brakes, through high interest rates and quantitative tightening.

Inflation rates have eased, though core inflation rates declined more gradually and remain higher than central bank targets, with actual and expected price inflation feeding into cost-of-living wage and salary increases, further fuelling inflation.

Will monetary tightening result in lower inflationary pressures and usher in lower interest rates in 2024? Financial markets focused on data-driven central banks are over-optimistic, exhibiting soft-landing exuberance.

Short-termism disregards economic fundamentals and neglects growing geopolitical risks, which the markets have failed to price in.

First and foremost, 2024 is an election year in 64 countries, together representing over four billion people. Governments do not cut spending in election years, let alone with rising populism in advanced, and many emerging, markets.

The biggest overhanging risk is the US. Elections are taking place in a highly divided and divisive political landscape, with no parties willing to undertake spending cuts.

US budget deficits are running at 6 to 7 percent of GDP, which is unprecedented in a near-full employment economy. The Biden administration is also requesting additional spending of some $115 billion to finance Ukraine and Israel.

US Treasury funding in 2024 will be flooding markets with $4 trillion in issuance, and net issuance is set to increase to about $1.9 trillion. Investors are unlikely to absorb surging borrowing at lower interest rates.

What’s more, the growing calls from the US, EU and UK for further decoupling from China increase the risk of disrupting global supply chains, leading to lower global growth and higher inflation rates.

Defence spending has also been rapidly rising and is likely to increase further given growing geopolitical flashpoints, the New Cold War and the potential risks of military confrontation with China in a US election year.

World military spending had already reached a new record high of $877 billion in 2022 (39 percent higher compared to 2021), with the US not only the world’s largest military spender but also spending more on defence than the next 10 countries combined.

The ongoing conflict in Gaza could spill over to include other countries, engulfing the GCC and Iran and threatening global trade and energy supplies.

Marine war risk premiums have soared almost 50-fold since before the war, about 0.7 percent to 1 percent of the value of the ship; war risk rates for shipping in the Black Sea from Ukraine can range up to 3 percent.

The bottom line is that markets face a growing risk of debt crises, high interest rates, rising debt service burdens, high levels of inflation, weakening currencies and slower growth.

Rather than a goldilocks scenario, 2024 is likely to be a bumpy ride for economies and financial markets dominated by short-termism to the neglect of economic fundamentals and growing geopolitical and geostrategic risks.