Weekly Insights 4 Nov 2020: Rising budget deficits & debt levels in the Middle East/ GCC Require Sustained Fiscal Adjustment

Download a PDF copy of this week’s insight piece here.

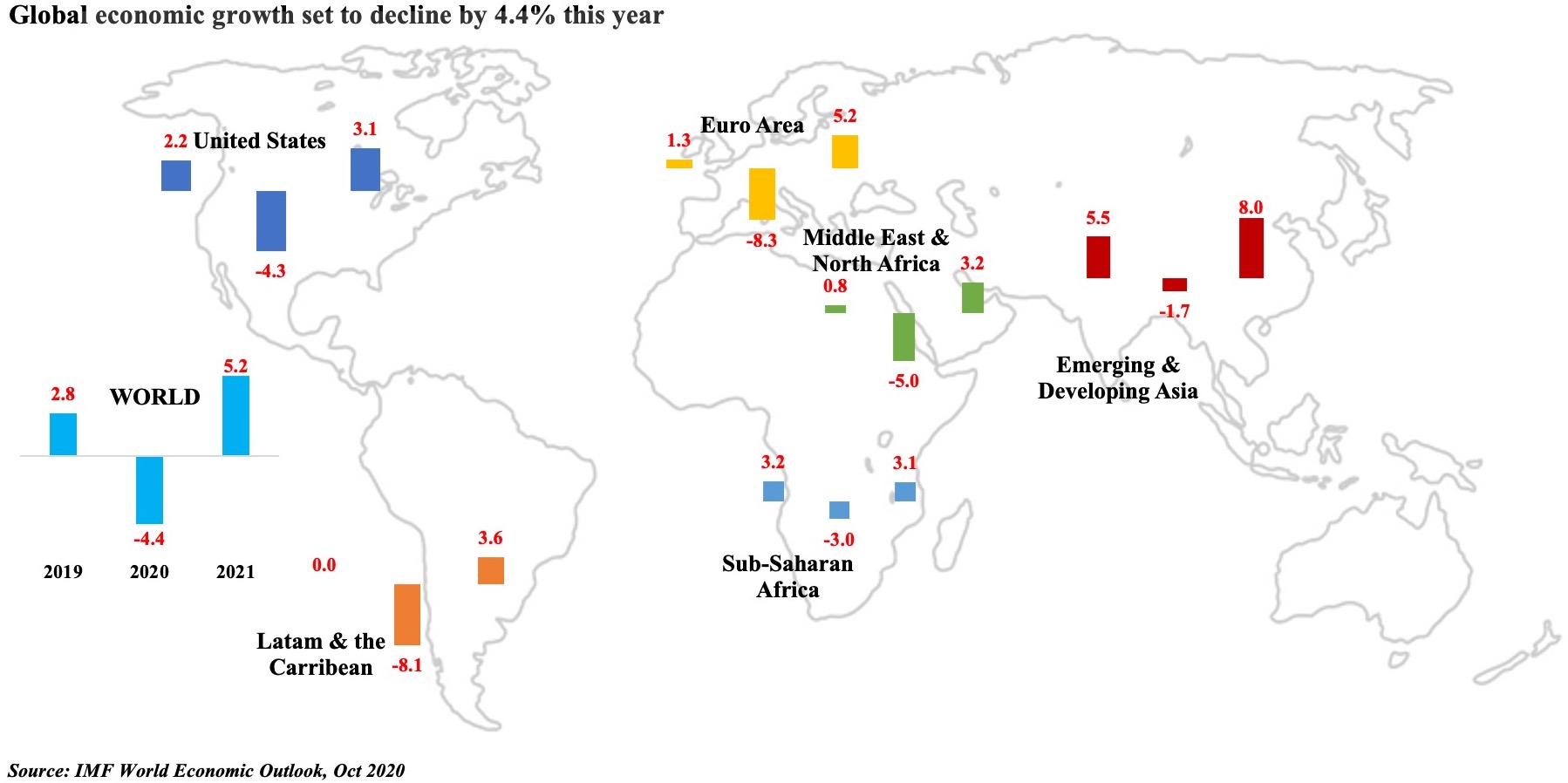

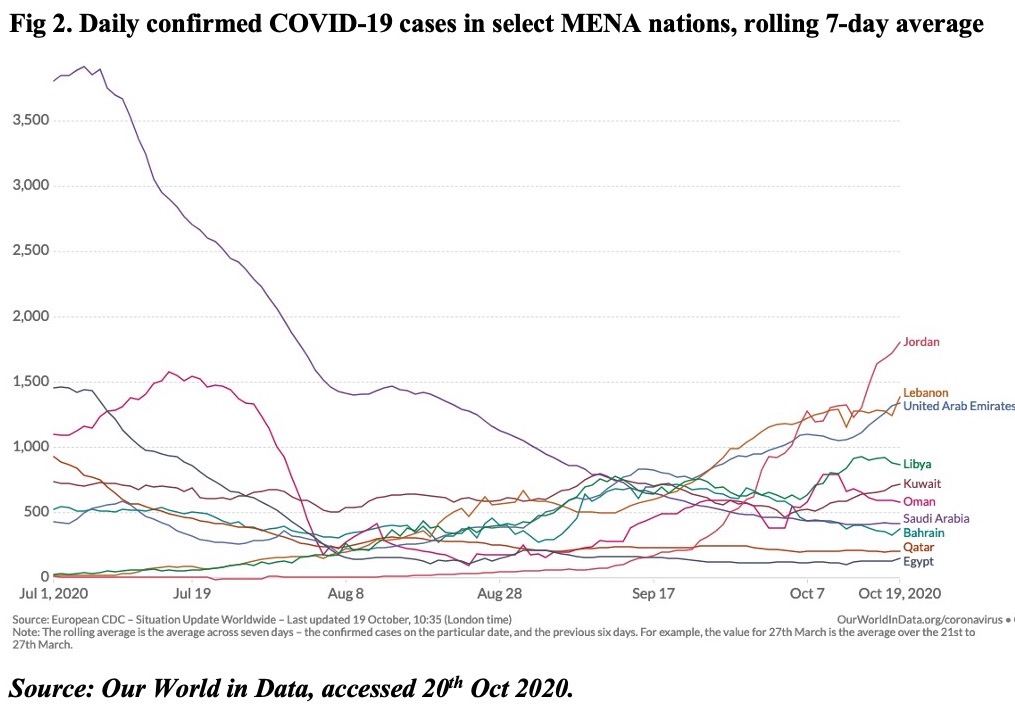

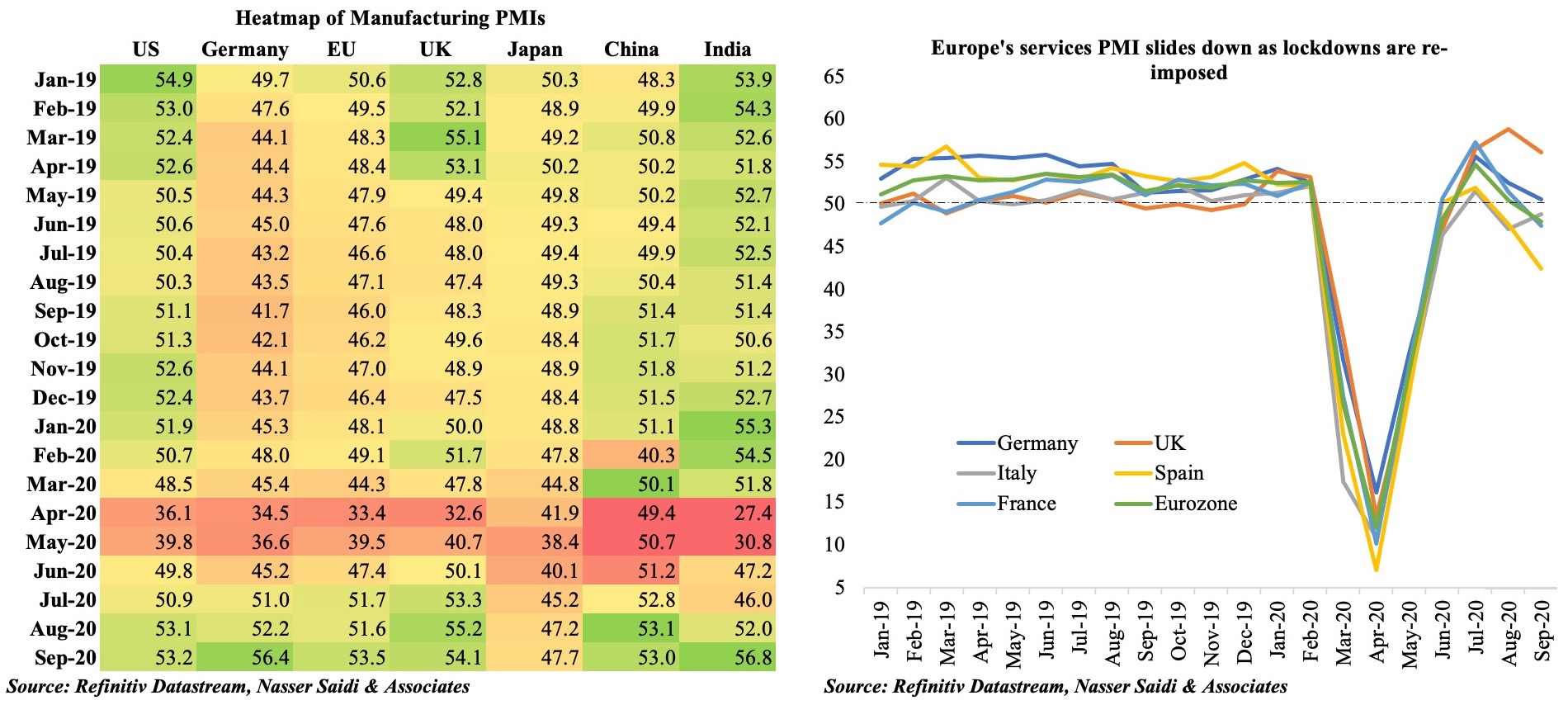

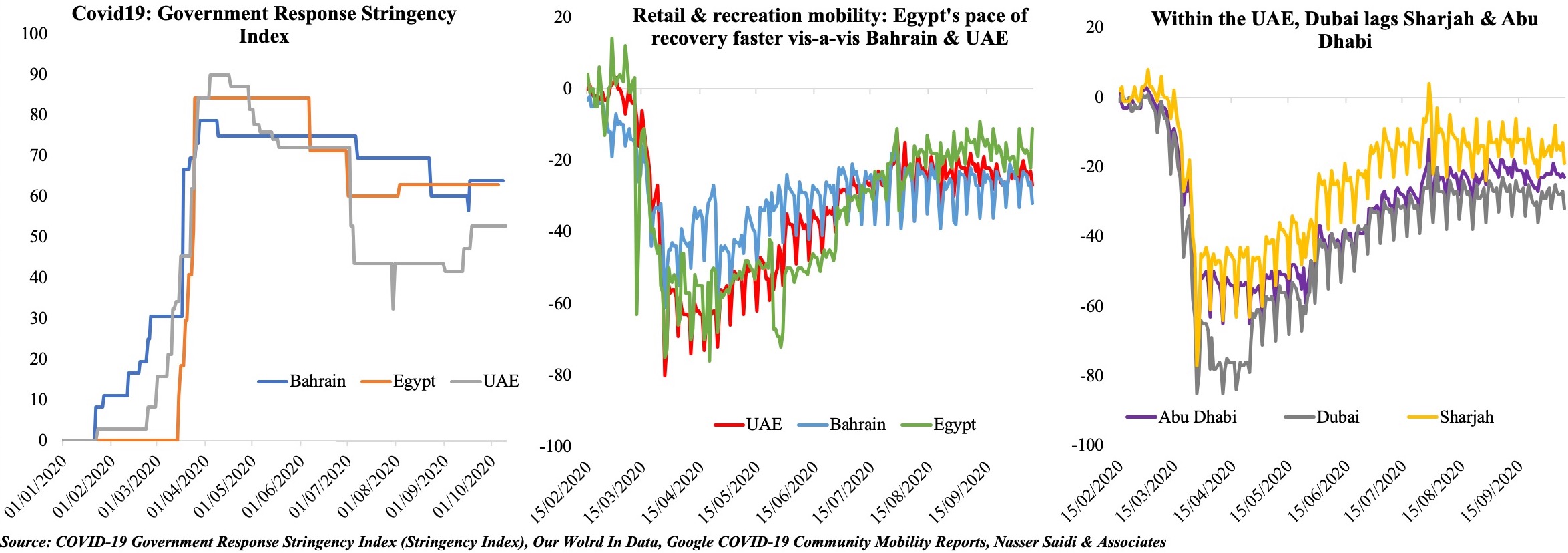

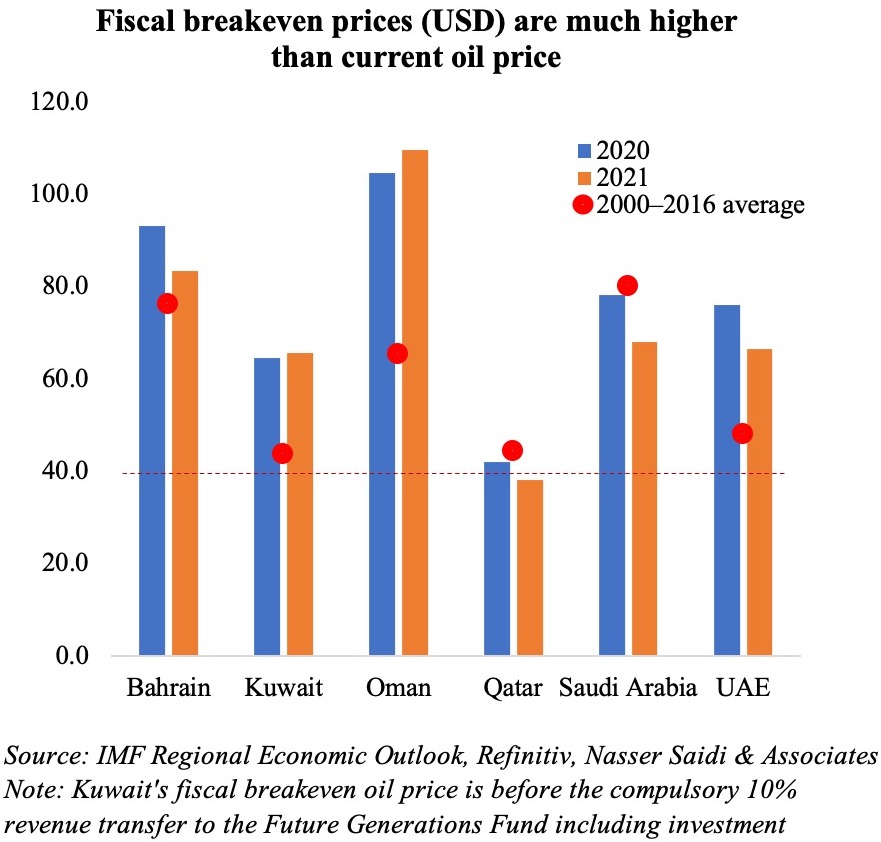

As the world awaits results of the US election, oil prices have settled around the forty-dollar mark. Oil exporters in the region have had to deal with the Covid19 outbreak along with a global recession that have drastically reduced the demand for oil, as well as lower oil prices.  Given the resurgence in Covid19 cases and renewed lockdown measures and the global energy transition away from fossil fuels, it is unlikely that oil prices will revert to the levels seen a few years ago, given weaker demand – the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook puts oil prices, based on futures markets at USD 41.69 in 2020 and USD 46.70 in 2021 (versus an average price of USD 61.39 last year). Fiscal breakeven oil prices in the GCC range between USD 42 for Qatar to USD 104.5 for Oman this year, exerting additional pressure on most oil producers as they ramp up spending to support the economy (UAE’s emirates Dubai and Sharjah announced USD136Mn and USD139Mn respectively in additional stimulus in the last few days).

Given the resurgence in Covid19 cases and renewed lockdown measures and the global energy transition away from fossil fuels, it is unlikely that oil prices will revert to the levels seen a few years ago, given weaker demand – the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook puts oil prices, based on futures markets at USD 41.69 in 2020 and USD 46.70 in 2021 (versus an average price of USD 61.39 last year). Fiscal breakeven oil prices in the GCC range between USD 42 for Qatar to USD 104.5 for Oman this year, exerting additional pressure on most oil producers as they ramp up spending to support the economy (UAE’s emirates Dubai and Sharjah announced USD136Mn and USD139Mn respectively in additional stimulus in the last few days).

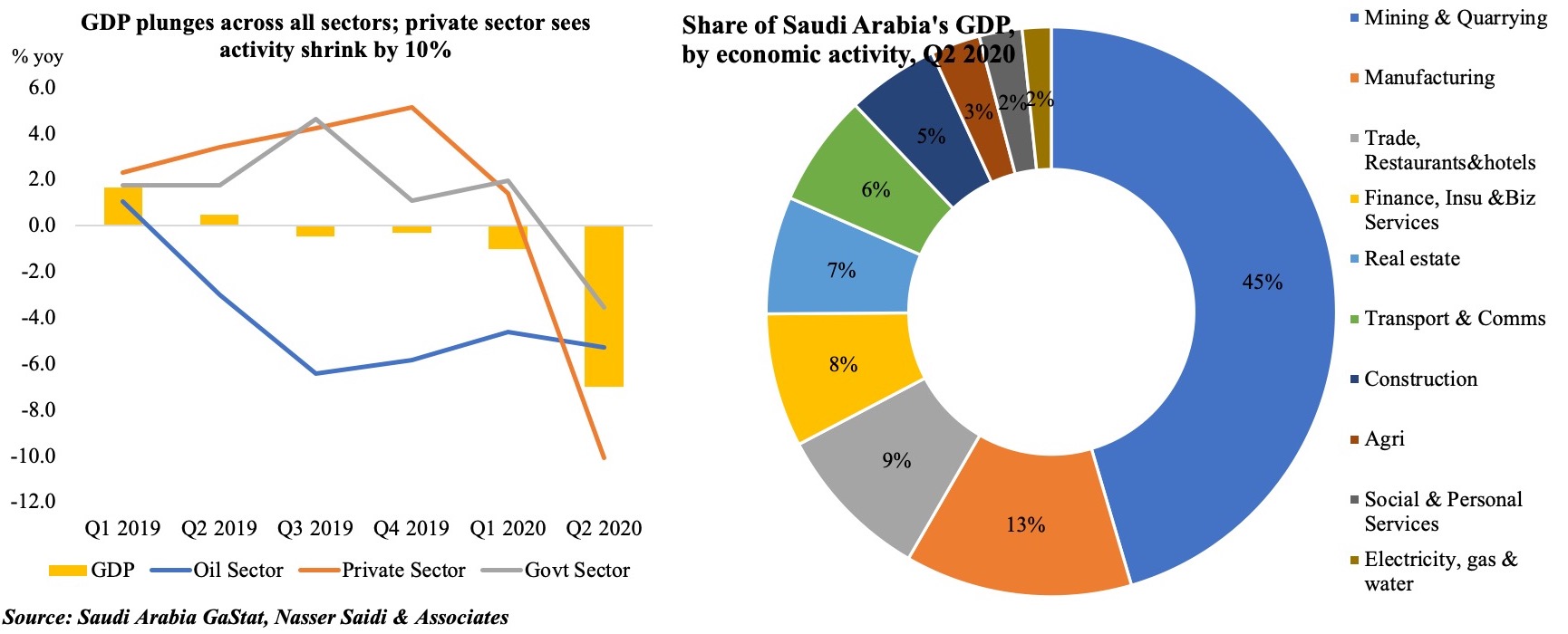

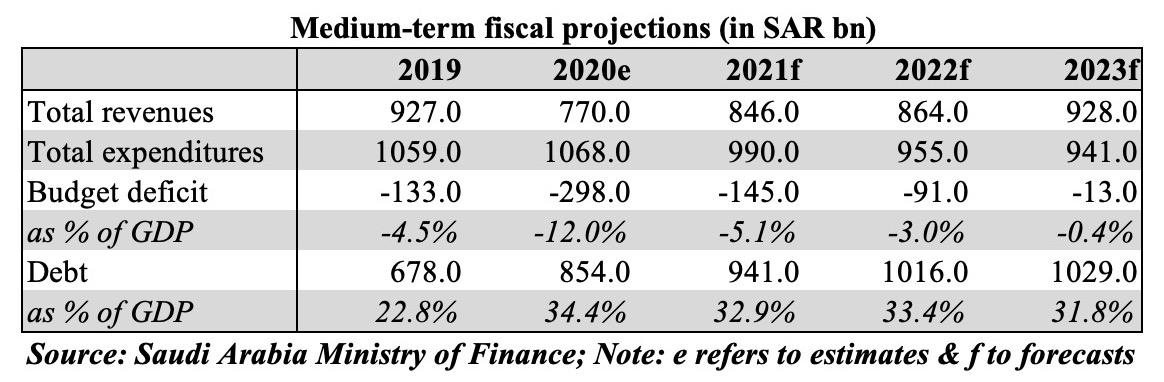

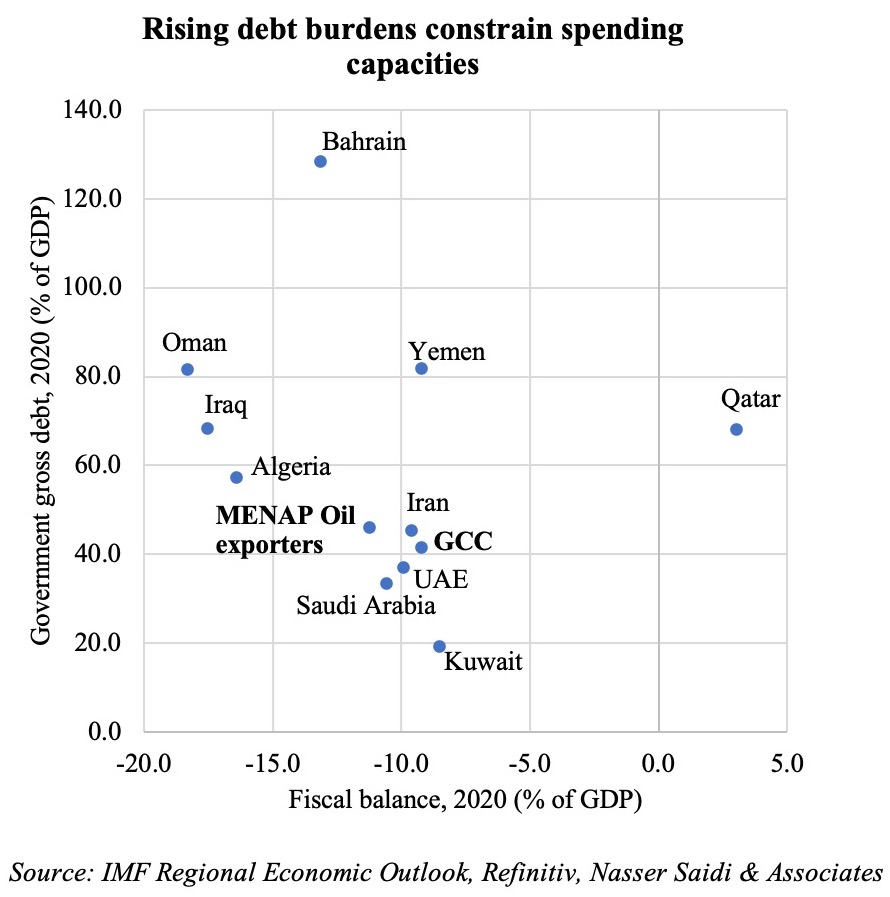

Oil exporters in the region are still highly dependent on oil revenues, with lower oil revenues implying limited fiscal room and higher fiscal deficits, which are averaging 10% in 2020 for the GCC countries. As real oil prices trend downward, fiscal sustainability becomes increasingly vulnerable.

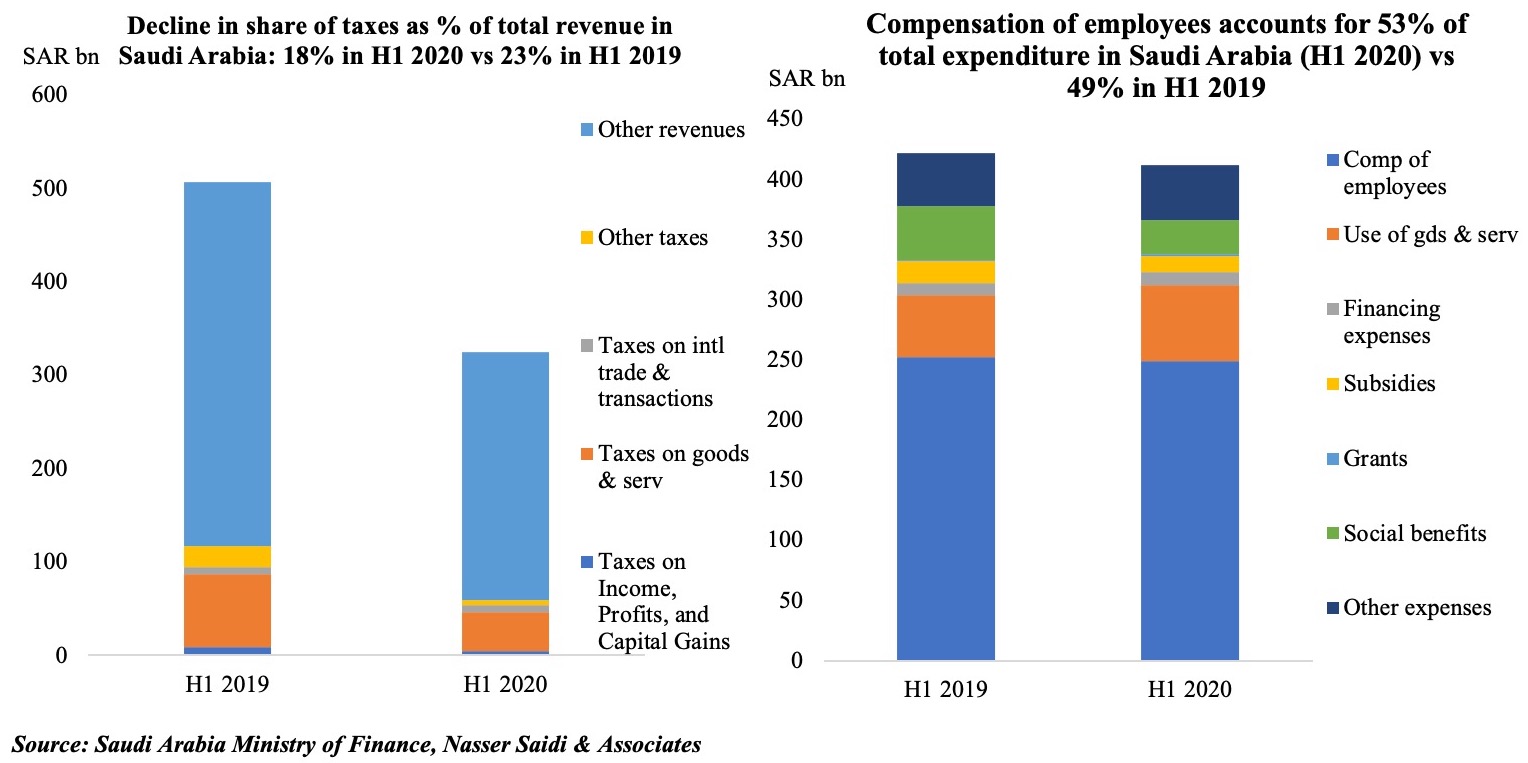

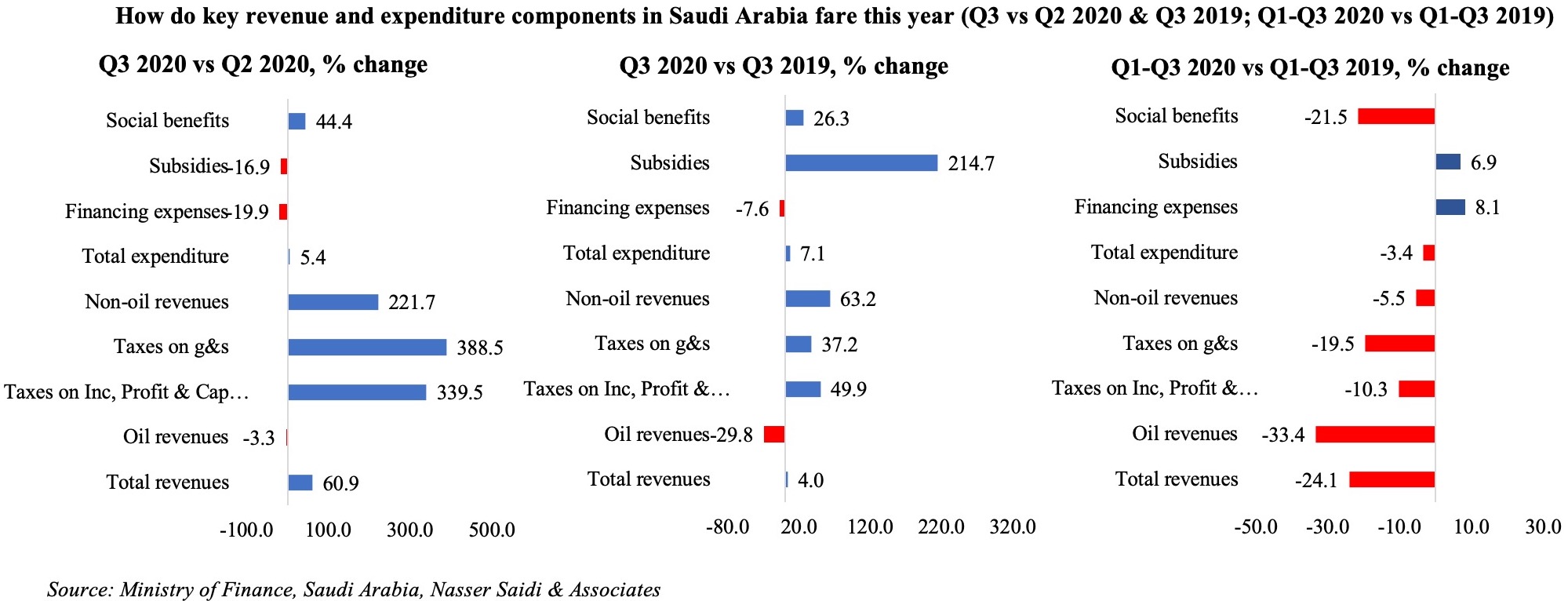

The latest numbers from Saudi Arabia underscore the need to diversify away from dependence on oil revenues. Saudi Arabia managed to halve its fiscal deficit in Q3 compared to Q2, as overall revenues edged up by 4% yoy, thanks in part to the 63% surge in non-oil revenues (VAT rate was hiked to 15% From Jul onwards); however, spending increased by 7% yoy, driven by a massive surge in subsidies to SAR 8.2bn (From SAR 2.2bn a year ago) brought on by the need to support the economy during the Covid19 outbreak.

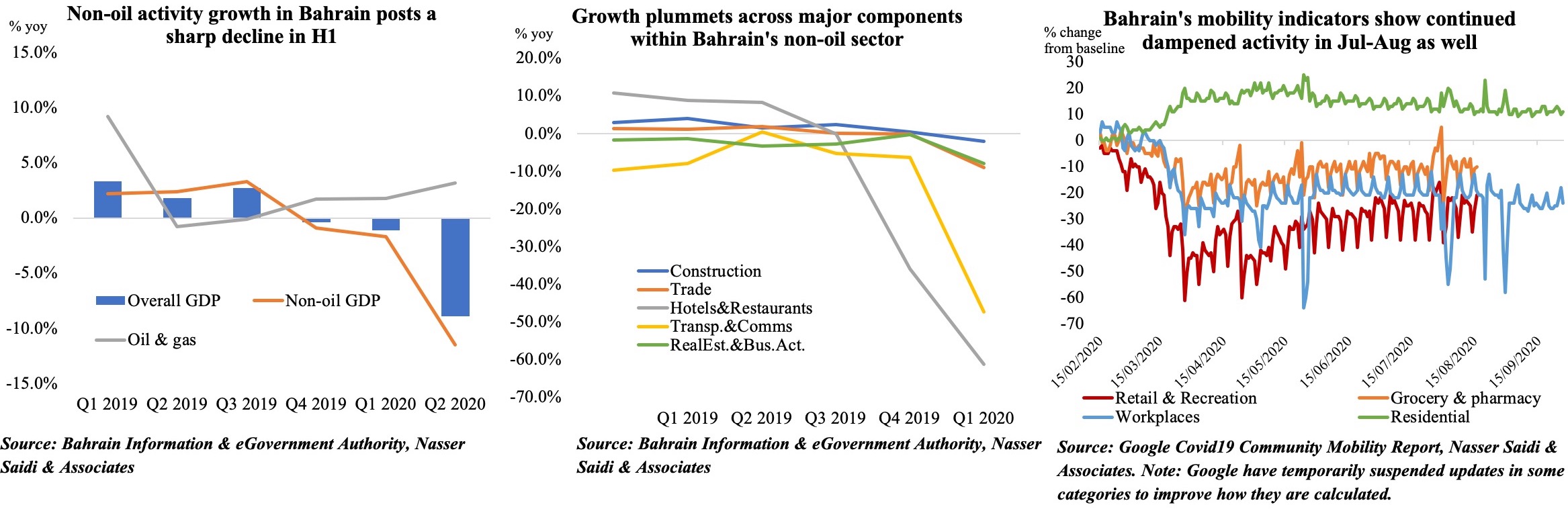

Among other GCC nations, Oman, in a bid to raise non-oil revenues, announced plans to introduce 5% VAT from next year, in addition to potentially introducing an income tax (currently being studied). Furthermore, costs of expatriates’ employment visa and work permit renewals will be increased by 5%, with a plan to redirect additional funds towards financing its recently initiated Job Security System. Kuwait meanwhile is facing the highest budget deficit in its history[1]. In Aug this year, the national assembly approved a law that makes transfers to the Future Generations Fund dependent on budget surplus, thus providing a much needed[2] but momentary respite. However, the Parliament is still holding the public debt law – which would allow the government to borrow KWD 20bn over 30 years – hostage. Bahrain’s deficit widened by 98% yoy in H1 this year (as oil revenues fell by 35% and overall revenues by 29%), leading it to issue a USD 1bn bond, while receiving a payment from its GCC neighbours (part of a support package approved in 2018).

Rising fiscal deficits following the previous decline in oil prices and lower growth have resulted in an accumulation of debt across all the MENA countries. The rising debt burdens and their servicing, leave limited space for increasing spending at a time when it is needed to support the economies. The IMF revealed that the median size of revenue and expenditure packages in the region’s oil importing countries this year was double that of oil exporters (2% of GDP versus 1% of GDP). For the GCC, adjustment has resulted from a combination of spending cuts, borrowing from commercial banks, tapping international/ regional markets (bond issuances[3], commercial loans) as well as drawing down from international reserves at the central banks and in Oman’s case direct external financial support from Qatar (with talks ongoing with the UAE, reports FT). As for support from sovereign wealth funds, given lack of transparent data, it will be difficult to gauge the actual value of their support/ contribution, but their optimal role would be to: (a) tap into investments abroad (starting with sale of money market instruments like T-bills); (b) re-assess long-term investment strategies to play a larger role domestically in supporting local industries, innovation and developing digital assets.

Faced with a complex situation, it is little wonder that measures to increase non-oil revenue are being introduced – Oman’s plan to introduce VAT in 2021, rise in visa fees and a potential income tax on high income earners and Saudi Arabia’s VAT hike. To achieve and maintain fiscal sustainability in the long-run, oil exporters will need to move away from pro-cyclical policies, rationalise overly generous and unsustainable entitlement programs, alongside revenue-enhancing measures. The policy agenda is full in the coming years!

|

Expenditure reduction policies |

Revenue enhancing measures |

Other measures |

| Phase out subsidies Reduce current spending Reduce public sector wage bills |

Raise non-oil fiscal revenues by raising taxes / introduce new taxes Improve efficiency in collecting taxes Consolidate/ rationalize fees/ charges on government services |

Allow deficit financing / create local currency debt & mortgage markets Public investment towards infrastructure to ensure a steady pipeline Establish social safety nets / pensions scheme |

[1] Kuwait posted a fiscal deficit of KWD 5.64bn in 2019-2020 (ending Mar 2020): this was higher by 69% yoy and inclusive of a KWD 1.72bn (10% of total annual revenues) transfer to the Future Generations Fund.

[2] The finance minister stated in Aug 2020 that the country has just KWD 2bn (USD 6.6bn) worth of liquidity in its Treasury and it was not enough to cover state salaries beyond Oct.

[3] Abu Dhabi issued a USD 5bn multi-tranche bond; Dubai sold USD 2bn in bonds; Saudi Arabia sold USD 7bn in 3-part bonds; Qatar sold USD 10bn in USD-denominated bonds.