The global economic meltdown has demonstrated that pan-regional financial systems that are heavily reliant on commercial banks for corporate funding are either potentially crisis prone or seriously impaired. This is particularly true if banks must suffer the pains of recapitalization, deleveraging, restructuring and de-risking, as is happening in most European countries.

By contrast, financial systems that are dependent on bond markets are enjoying more reliable and cheaper access to new funding resources. In the US, for instance, the average yields on junk-rated debt fell to a record low of below 6% in the first week of 2013.

Beyond the short-term and often volatile opportunities, recent economic history has shown that bond markets are naturally fungible as a leading channel of liquidity for governments, as well as public and private companies. Even those regions (both mature and emerging) whose banking systems are still sound display a structural trend towards strong bond market development.

The name of the game is capital market disintermediation, which will occur, sooner or later, either in a vicious or virtuous way.

It may be a case of the former for continental Europe, where the combined effects of the required accelerated deleveraging (as mandated by global capital standards) along with forthcoming “mark-to-market” of non-performing loans (NPLs), could drive to a strong and rapid contraction in banks’ commercial lending supply.

It may, more optimistically, be the latter for the MENA region, where banks enjoy a relatively better funding structure with more reasonable loan-to-deposit ratios, coupled with higher interest margins, nominally stronger capital base and higher profitability ratios.

Still, the case for the disintermediation of traditional banks’ funding channel is laid out due to a number of fundamentally safe and sound reasons:

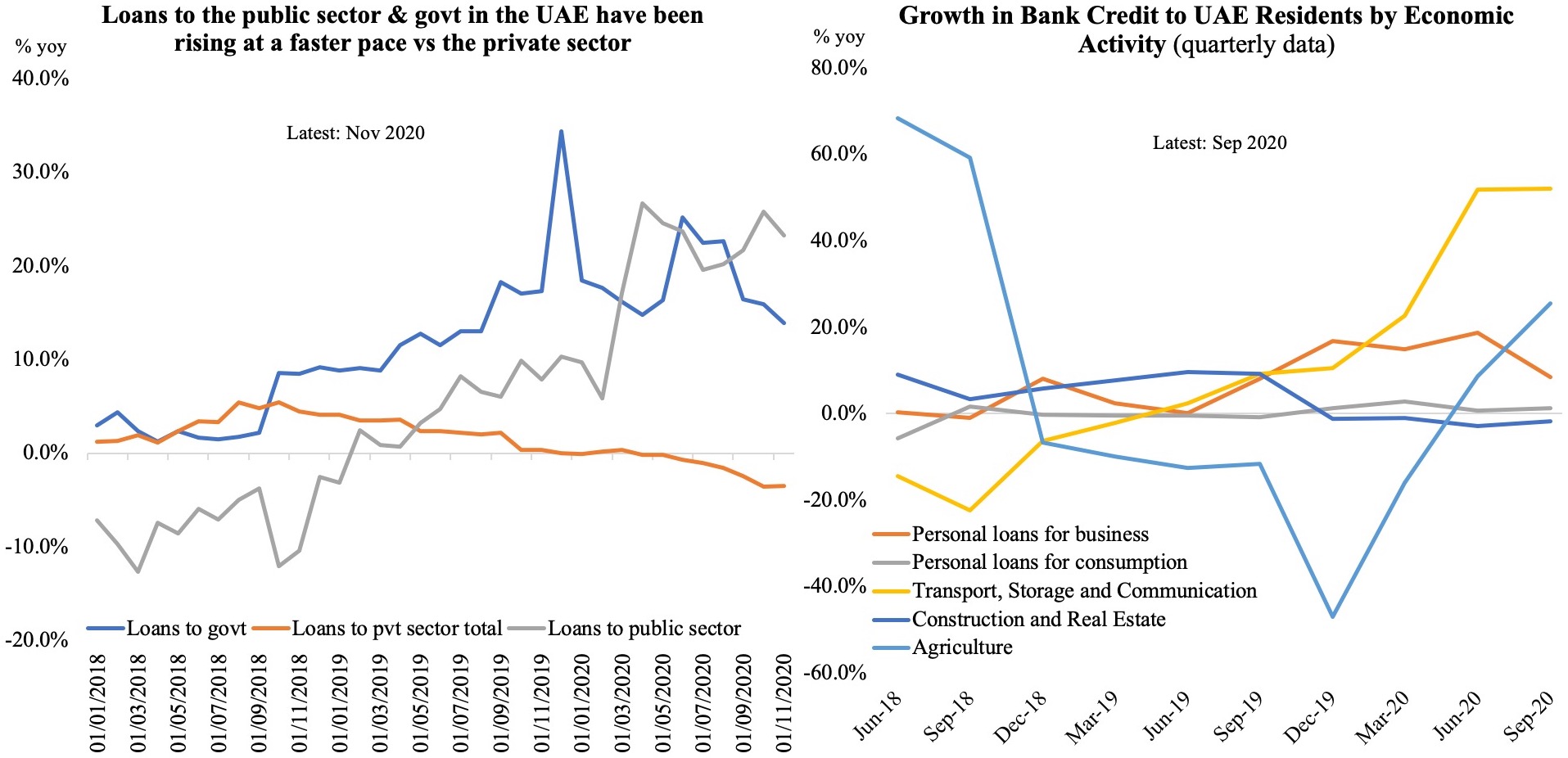

- The regulatory case for deleveraging, and the effect of the forthcoming mark-to-market of NPLs on real estate lending (with particular reference to the UAE and Kuwait), will also hurt MENA commercial banks’ lending capacity;

- The high interest margin charged on corporate lending appears less attractive when compared with the true cost of credit. It is startling that a top-rated company in the MENA region borrows at an interest of 10-12%, while a subpar firm in the US at half the rate through junk bonds. Self-financing, other pockets of “shadow financing” and the international capital markets will start competing more aggressively as regional banks threaten the direct funding business. In particular, “shadow financing” and capital markets benefit from the comparative advantage of softer regulation, lower cost of funding and larger economies since these provide a variety of financing options.

Addressing the issue

The solution is to push for the development of local currency fixed income markets (both conventional and Islamic) in order to ensure stable access to new funds. This move not only creates a yield curve that will price all kinds of financial assets transparently, but also provides monetary policy tools and enables the development of risk management techniques.

Deeper bond markets in local currencies will likewise allow open economies to better absorb volatile capital flows. As well as provide institutional investors with instruments that satisfy their demand for safe and stable long-term yields, locally denominated debts can guarantee a stable source of capital and reduce financial instability associated with asset price .

Considering the heavy investments needed in MENA’s infrastructure projects, it is ideal to raise financing through securities backed by future cash flows from the infrastructure services, as is typical of project-financing schemes.

On macro-economic terms, the development of a strong, liquid and transparent local currency bond market would be highly beneficial for the economies of MENA. This will improve the optimal allocation of financial resources in the overall system.

As it stands now, the MENA nations lack the important ingredients of a well-functioning debt capital market. These elements include a credit rating culture, market transparency, benchmarks, long maturities, a broad spectrum of institutional investors and a derivatives market for managing interest rate and credit risk.

Disintermediation to benefit banks

Only recently, a credit default swap (CDS) OTC market has gained prominence, but it is still in its infancy. On micro-economic terms, the disintermediation to come could also benefit the banking system in at least two ways:

Firstly, the proactively controlled re-composition of MENA banks’ balance sheets, profit and loss accounts would prevent abrupt and negative impacts on their financial stability and value creation capacity. The loss in net interest margin from direct loans could be gradually replaced -at least partially – by the higher fees coming from debt capital market structuring and placing activities.

The deleveraging and de-risking of the banking system would liberate financial and commercial resources for redeployment in more innovative and value adding activities (from asset management to bank-assurance; from private banking to corporate advisory). It will also reduce credit charges as well as the formation of NPLs.

In order to achieve this, regional banks should consider the opportunity of building some smart investment banking capabilities: focusing internally on the product design and risk management activities while considering third party alliances for the more standardized ones.

Secondly, MENA banks could benefit directly from the development of an efficient bond market that could help them pursue a longer term and cheaper liability structure – therefore reducing the currently high asset-liability management (ALM) imbalance.

We feel that a medium-term notes (MTNs) market for domestic banks that are active in the region could be an achievable target for the short term and a first step in the right direction. Such initiative should be considered a high priority project for policy makers, central banks and regulatory bodies.

In order to strengthen MENA’s local bond market, governments must express strong commitment to implementing a proactive debt management program (DMP). Part of this scheme should include extensive marketing and communication effort aimed at institutional global investors.

The DMP aimed at the development of an MTN market for domestic banks should start identifying and supporting focused issuance programs for local banking champions, thereby helping them access international investors.

It could also consider the creation of a “bond of bonds”, which can pool together the issuance needs of mid to small banking players, thus creating diversification in terms of names, countries and sub-sector of activities.

Eventually, some form of credit enhancement through credit protection on the first loss or on specific senior and super senior tranches, could be considered and provided by government-owned financial guarantees and credit insurance entities.

Last, but not the least, money markets and financial derivative markets should be developed alongside the debt capital markets to facilitate liquidity management by both central banks and investors.

[This article was co-authored with Claudio Scardovi of AlixPartners and published by Zawya]

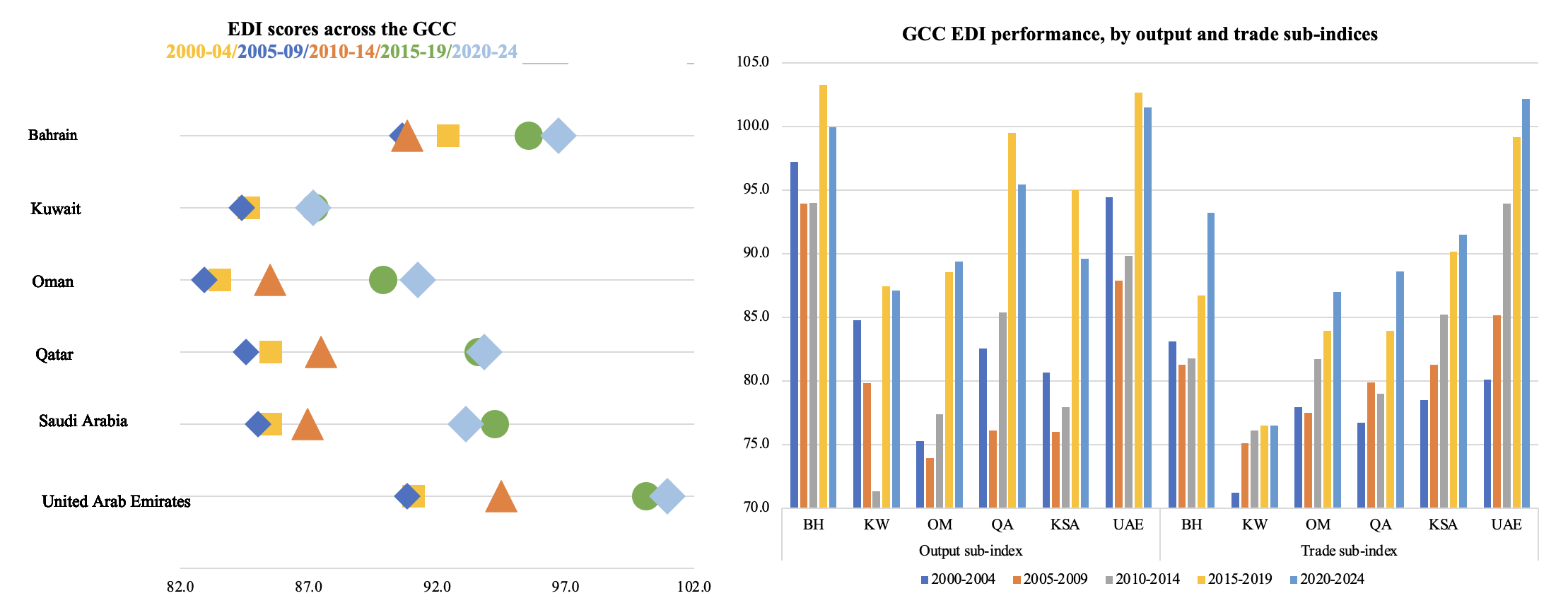

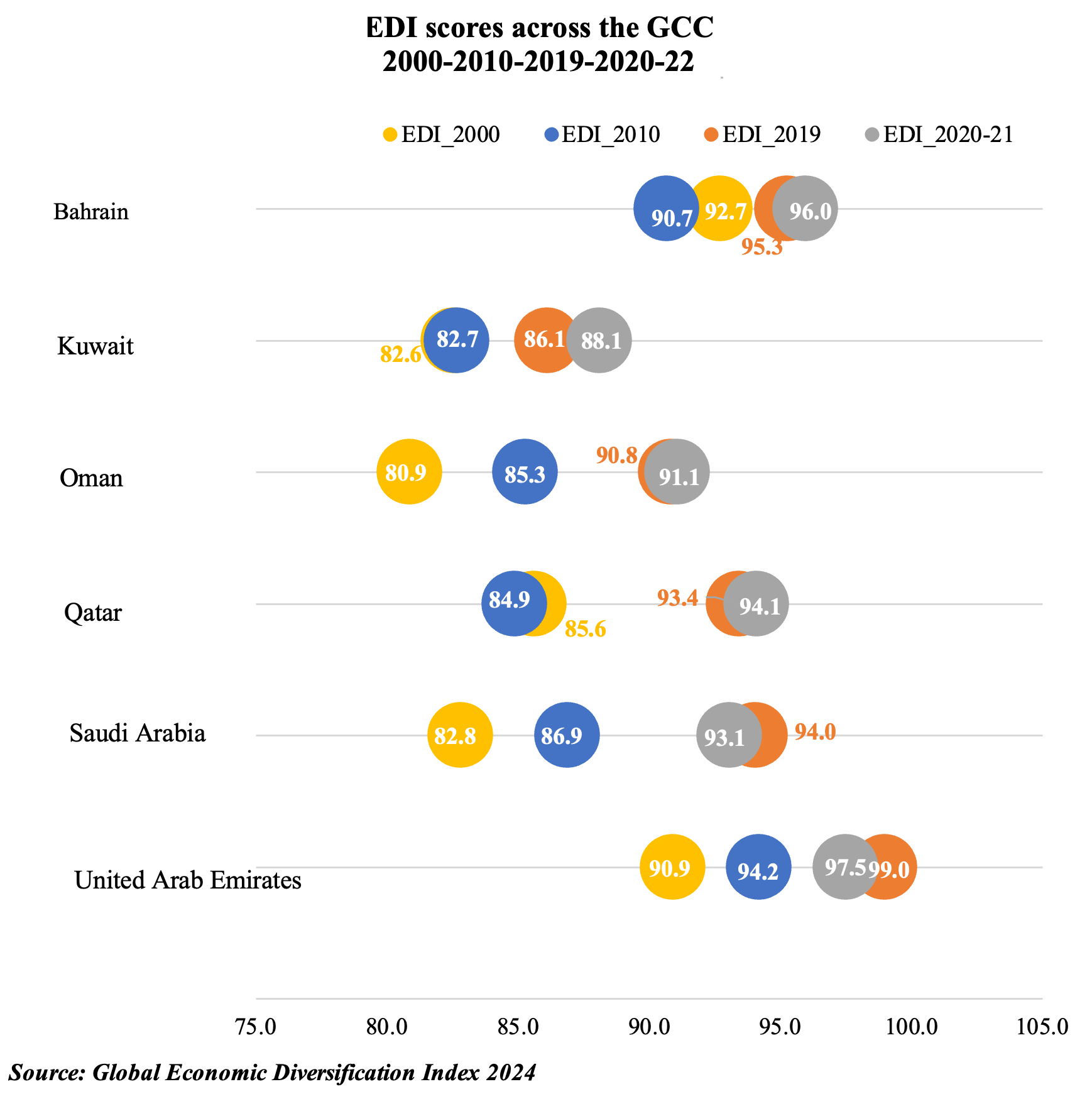

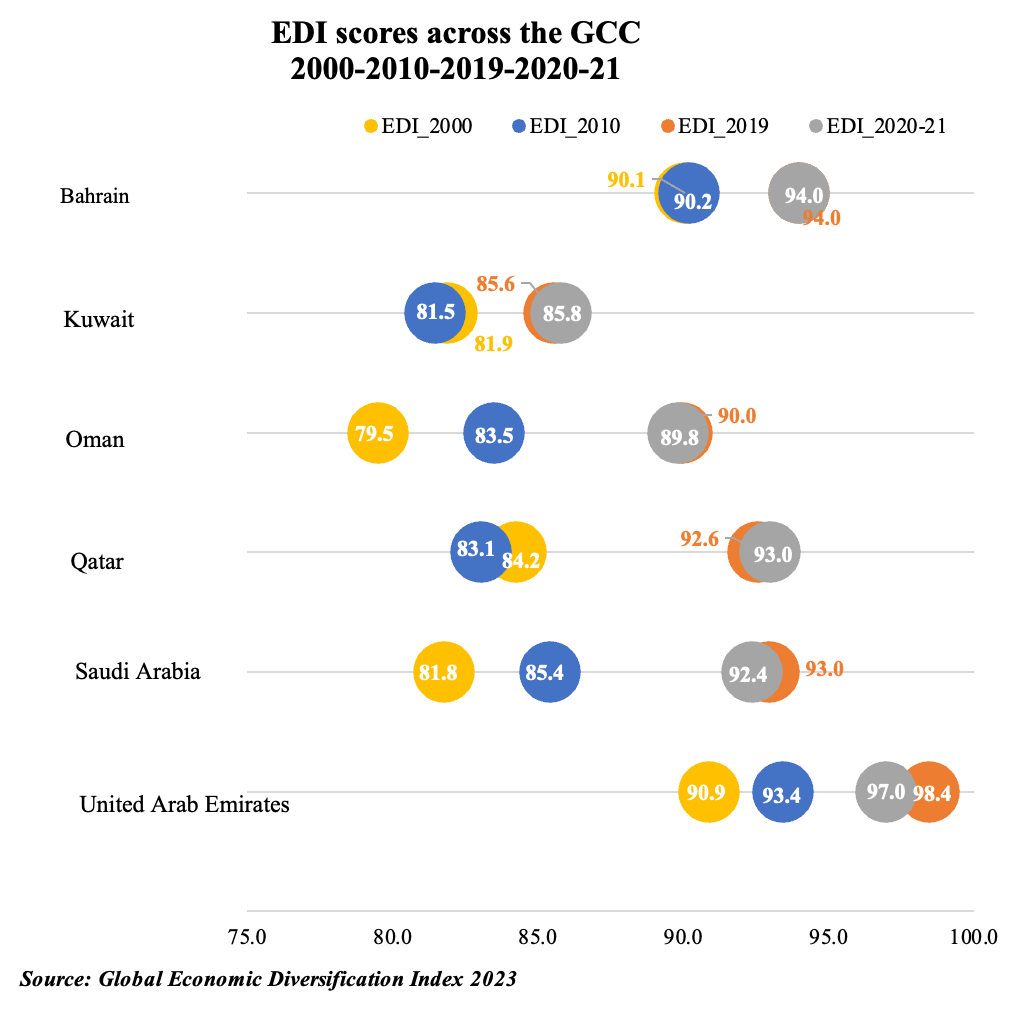

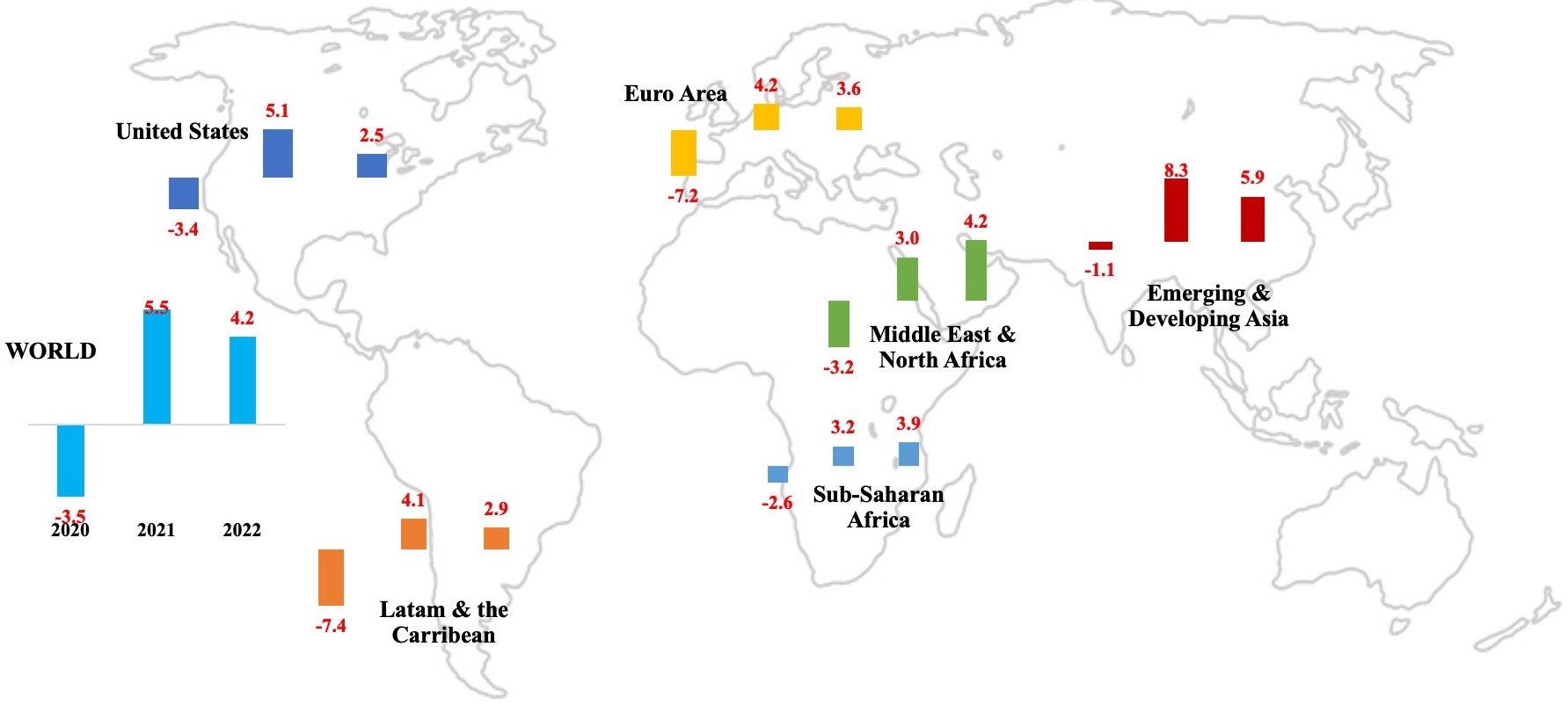

negative impact on performance but also the divergent paces of recovery. However, both the MENA and Eastern Europe & Central Asia regions reported a slight improvement in the 2020-2022 period versus pre-pandemic scores: these nations were all fuel exporters (i.e. not exporters of any other commodities). The report also finds that countries that reduced (increased) the share of resource rents have seen an increase (decline) in EDI scores, but the relation is one of correlation and not causation. Among the GCC, UAE and Bahrain have higher EDI scores compared to their peers, while Saudi Arabia and Oman have both gained over 10-points in 2020-2022 compared to their EDI score in 2000. Improvements in GCC scores have resulted from the implementation of reforms at a much more aggressive pace after the pandemic – including incentives to invest in new tech sectors, plans to broaden tax bases, trade liberalisation through free trade agreements and improvements to regulatory and business environment among others facilitating rights of establishment and labour mobility – that support diversification efforts and provide long-term economic resilience.

negative impact on performance but also the divergent paces of recovery. However, both the MENA and Eastern Europe & Central Asia regions reported a slight improvement in the 2020-2022 period versus pre-pandemic scores: these nations were all fuel exporters (i.e. not exporters of any other commodities). The report also finds that countries that reduced (increased) the share of resource rents have seen an increase (decline) in EDI scores, but the relation is one of correlation and not causation. Among the GCC, UAE and Bahrain have higher EDI scores compared to their peers, while Saudi Arabia and Oman have both gained over 10-points in 2020-2022 compared to their EDI score in 2000. Improvements in GCC scores have resulted from the implementation of reforms at a much more aggressive pace after the pandemic – including incentives to invest in new tech sectors, plans to broaden tax bases, trade liberalisation through free trade agreements and improvements to regulatory and business environment among others facilitating rights of establishment and labour mobility – that support diversification efforts and provide long-term economic resilience.

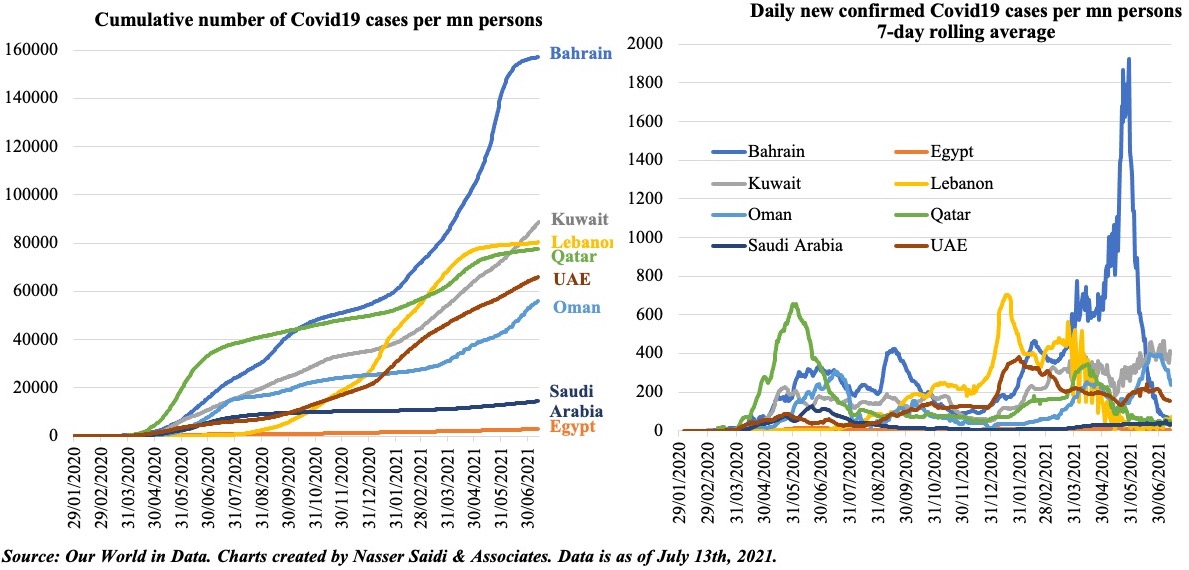

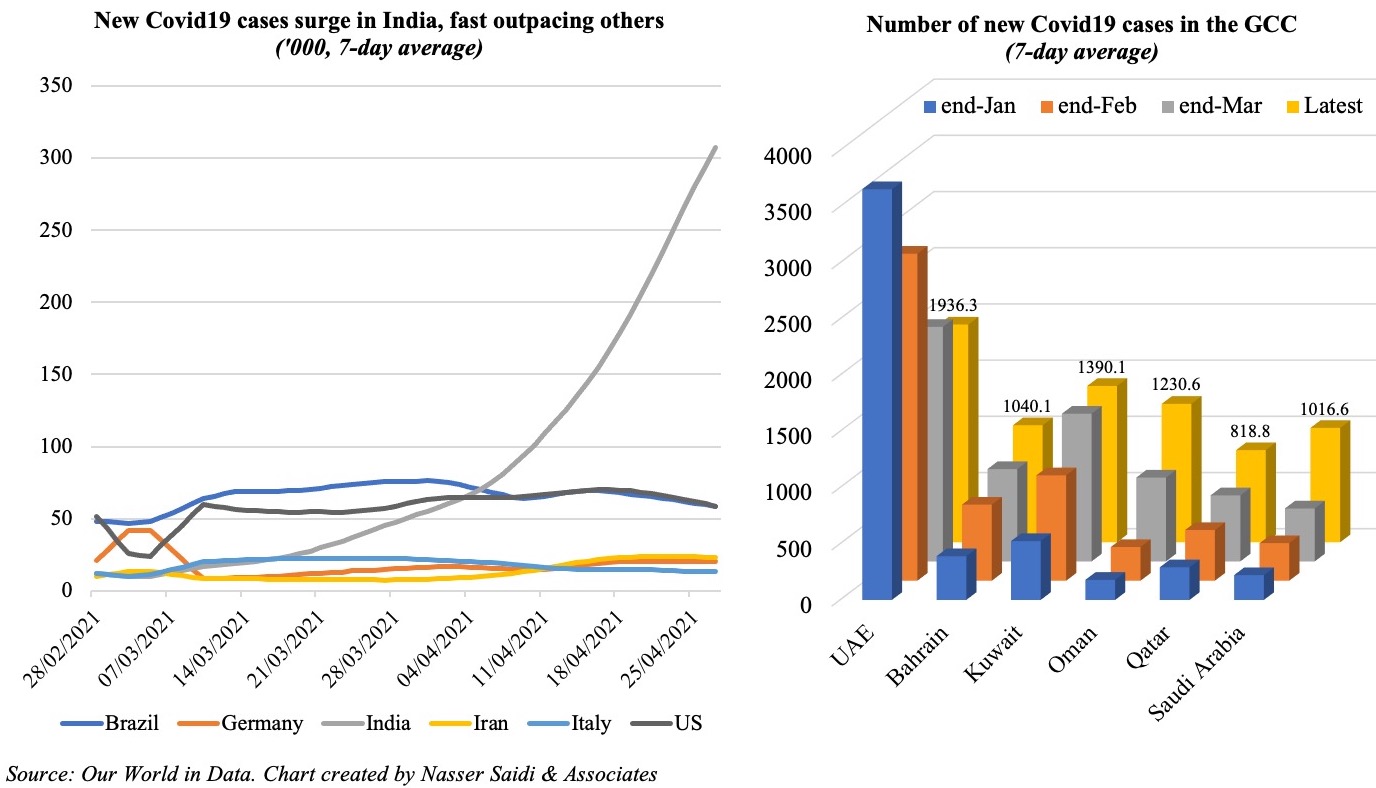

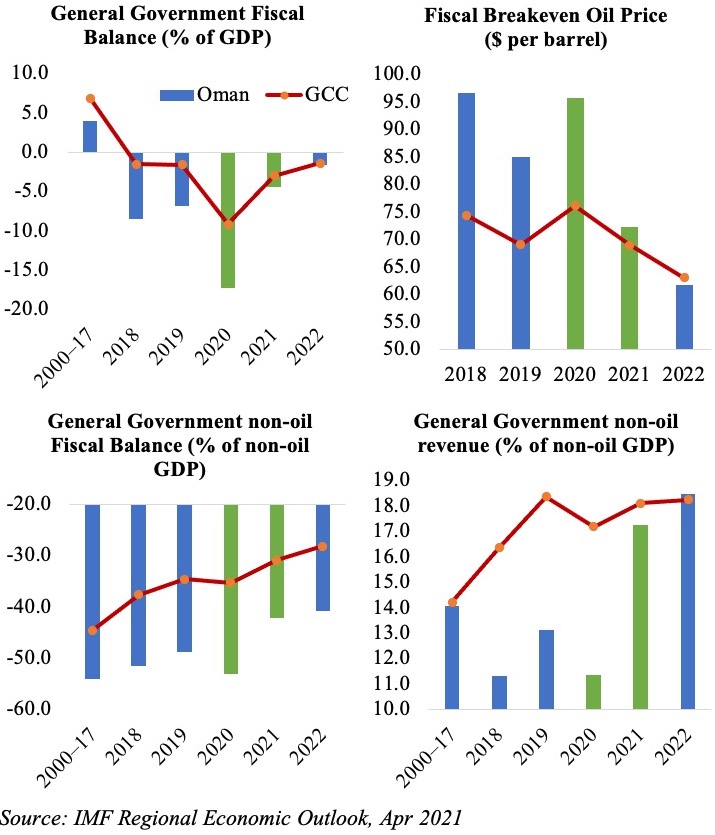

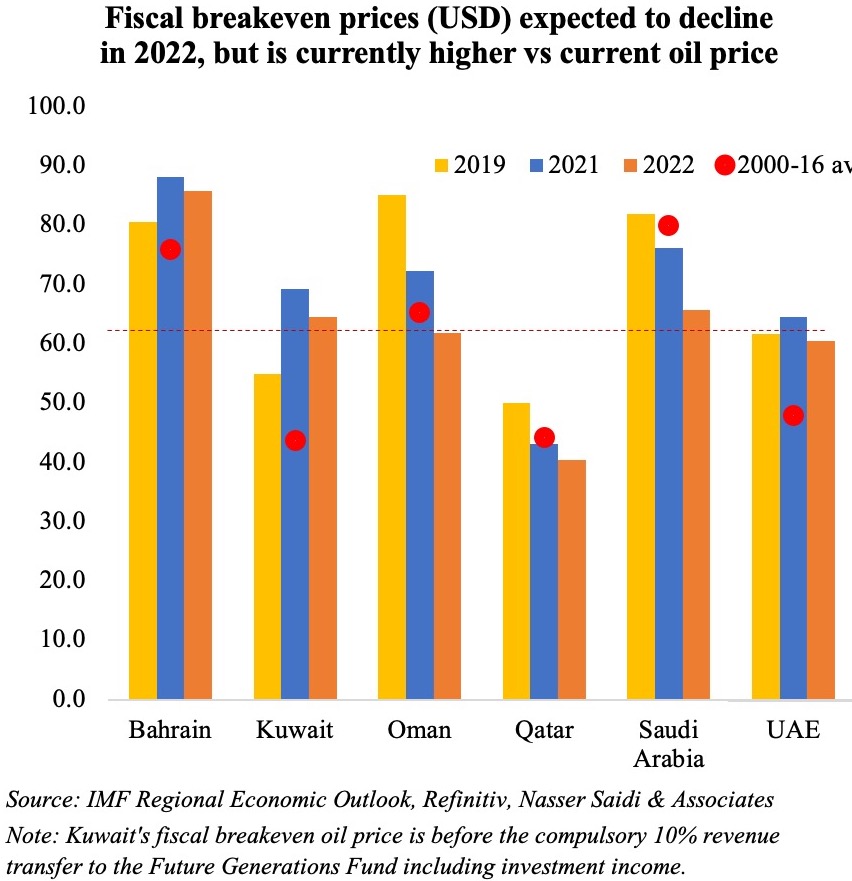

However, policy measures introduced to support the economy during the pandemic is creating immense fiscal strain. Fiscal deficits widened to 10.1% of GDP in 2020 in the MENA region from 3.8% in 2019. It was severe in the GCC as well: fiscal deficit widened to 7.6% of GDP last year (2019: -1.6%), as the impact was from both lower oil and non-oil revenues. The fiscal breakeven price this year ranges from a high USD 88.2 in Bahrain to a low USD 43.1 in Qatar. While, it is expected to decline across the board next year, it still remains higher than the current oil price levels for most nations. Given new rounds of restrictions and with oil demand not yet at pre-pandemic levels, the OPEC+’s recent decision to roll back production cuts are likely to depress oil prices. As real oil prices trend downward, fiscal sustainability becomes increasingly vulnerable.

However, policy measures introduced to support the economy during the pandemic is creating immense fiscal strain. Fiscal deficits widened to 10.1% of GDP in 2020 in the MENA region from 3.8% in 2019. It was severe in the GCC as well: fiscal deficit widened to 7.6% of GDP last year (2019: -1.6%), as the impact was from both lower oil and non-oil revenues. The fiscal breakeven price this year ranges from a high USD 88.2 in Bahrain to a low USD 43.1 in Qatar. While, it is expected to decline across the board next year, it still remains higher than the current oil price levels for most nations. Given new rounds of restrictions and with oil demand not yet at pre-pandemic levels, the OPEC+’s recent decision to roll back production cuts are likely to depress oil prices. As real oil prices trend downward, fiscal sustainability becomes increasingly vulnerable.

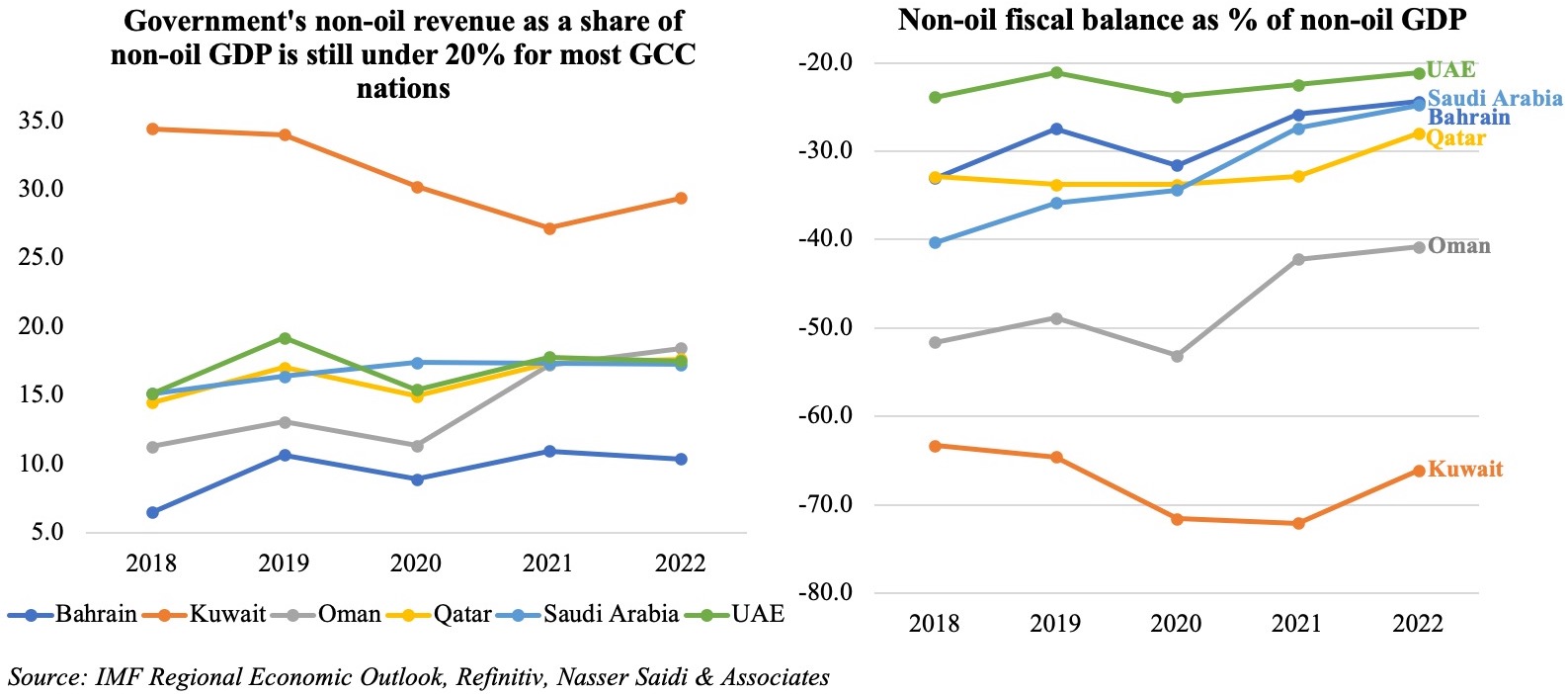

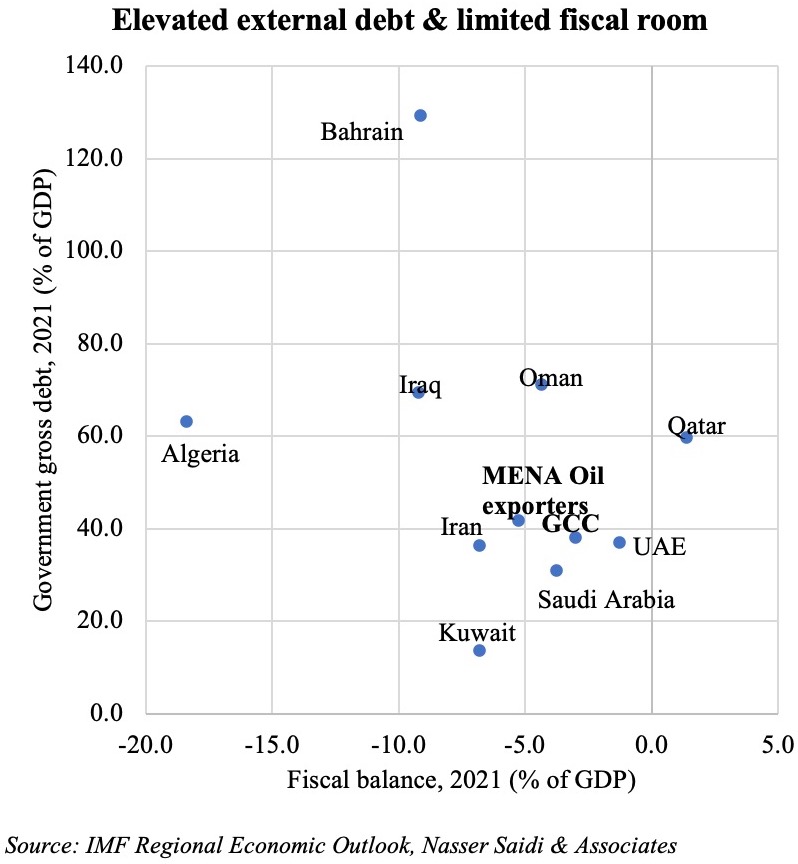

Higher deficits and negative economic growth resulted in governments resorting to multiple financing options: borrowing from commercial banks, tapping international and regional markets (bond issuances, commercial loans) as well as drawing down from international reserves at the central banks/ sovereign wealth funds. Government debt levels increased to 56.4% and 41% in the MENA and GCC regions last year. Though it is forecast to fall slightly this year, it still remains higher than the 2000-17 average of 36.2% and 24.6% respectively. The IMF estimates financing needs in the MENA to touch USD 919bn for this year and next. Public-financing requirements were likely to stay above 15% of GDP in most parts of the region through end-2022.

Higher deficits and negative economic growth resulted in governments resorting to multiple financing options: borrowing from commercial banks, tapping international and regional markets (bond issuances, commercial loans) as well as drawing down from international reserves at the central banks/ sovereign wealth funds. Government debt levels increased to 56.4% and 41% in the MENA and GCC regions last year. Though it is forecast to fall slightly this year, it still remains higher than the 2000-17 average of 36.2% and 24.6% respectively. The IMF estimates financing needs in the MENA to touch USD 919bn for this year and next. Public-financing requirements were likely to stay above 15% of GDP in most parts of the region through end-2022.

The human toll from violence in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) has reached historic proportions. Since 2000, an estimated 60% of the world’s conflict-related deaths have been in the MENA region, while violence in Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen continues to displace millions of people annually.

For countries hosting refugees from these conflicts, the challenges have been acute. According to a 2016 report by the International Monetary Fund, MENA states bordering high-intensity conflict zones have suffered an average annual GDP decline of 1.9 percentage points in recent years, while inflation has increased by an average of 2.8 percentage points.

Large influxes of refugees put downward pressure on a host country’s wages, exacerbating poverty and increasing social, economic, and political tensions. And yet most current aid strategies focus on short-term assistance rather than long-term integration. Given the scale and duration of MENA’s refugee crisis, it is clear that a new approach is needed, one that shifts the focus from temporary to semi-permanent solutions.

To accomplish this, three areas of refugee-related support need urgent attention. First, donor countries must do more to strengthen the economies of host states. For example, by buying more exports from host countries or helping to finance health-care and education sectors, donors could improve economic conditions for conflict-neighboring states and, in the process, create job opportunities for refugees.

For this to pay off, however, host countries will first need to remove restrictions on refugees’ ability to work legally. Allowing displaced people to participate in formal labor markets would enable them to earn an income, pay taxes, and eventually become less dependent on handouts as they develop skills that eventually can be used to rebuild their war-ravaged countries.

Employment might seem obvious, but most MENA host countries currently bar refugees from holding jobs in the formal sector (Jordan is one exception, having issued some 87,000 work permits to Syrian refugees since 2016). As a result, many refugees are forced to find work in the informal economy, where they can become vulnerable to exploitation and abuse.

But evidence from outside the region demonstrates that when integrated properly, refugees are more of a benefit than a drain on host countries’ labor markets. For example, a recent analysis by the Refugee Studies Centre at the University of Oxford found that in Uganda, refugee-run companies actually increase employment opportunities for citizens by significant margins.

A second issue that must be addressed is protecting refugees’ “identity,” both in terms of actual identification documents and cultural rights. For these reasons, efforts must be made to improve refugees’ digital connectivity, to ensure that they have access to their data and to their communities.

One way to do this would be by using blockchain technology to secure the United Nations’ refugee registration system. This would strengthen the delivery of food aid, enhance refugee mobility, and improve access to online-payment services, making it easier for refugees to earn and save money.

Improved access to communication networks would also help refugees stay connected with family and friends. By bringing the Internet to refugees, donor states would be supporting programs like “digital classrooms” and online health-care clinics, services that can be difficult to deliver in refugee communities. Displaced women, who are often the most isolated in resettlement situations, would be among the main beneficiaries.

Finally, when the conflicts end – and they eventually will – the international community must be ready to assist with reconstruction. After years of fighting, investment opportunities will emerge in places like Iraq, Syria, and Sudan, and for the displaced people of these countries, rebuilding will boost growth and create jobs. Regional construction strategies could reduce overall costs, increase efficiencies, and improve economies of scale.

In fact, the building blocks for the MENA region’s postwar period must be put in place now. For example, the establishment of a new Arab Bank for Reconstruction and Development would ensure that financing is available when the need arises. This financial institution – an idea I have discussed elsewhere – could easily be funded and led by the Gulf Cooperation Council with participation from the European Union, China, Japan, the United States, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and other international development actors.

With this three-pronged approach, it is possible to manage the worst refugee crisis the world has experienced in decades. By ensuring access to work, strengthening communication and digital access, and laying the groundwork for post-war reconstruction, the people of a shattered region can begin planning for a more prosperous future. The alternative – short-term aid that trickles in with no meaningful strategy – will produce only further disappointment.