The 2018 World Cup is steaming to a close, with a global build-up of excitement and anticipation. Over a 1.5 billion people are expected to watch the final. World Cup frenzy takes over homes, businesses (with a consequent drop of productivity) and even trading rooms, where volumes decline and sick leave shoots up. Even conservative economists get excited. But economists can also be spoilsports. Despite the euphoria, they ask: does it make sense to host mega events like the World Cup, Olympics or World Expos? Do host countries benefit and do they recoup the investments made?

The arguments for undertaking mega projects and events focus primarily on the direct economic impact. This is the increase in activity and employment in the engineering, procurement and construction sector related to infrastructure spending, along with increased employment and spending in the tourism sector resulting from the inflow of tourists into the country (though this might displace non-event tourism because of congestion costs), as well as an increase in consumer spending during the event.

Research by Vanquis Bank reveals that England fans travelling to Russia for the World Cup and attending all matches would have spent £5,090 (Dh24,643) or 22 per cent of the average UK annual salary if England had reached the final. FIFA estimates close to 2.6 million fans would have watched the games in Russia by the time it wraps up on Sunday, but this is less than 0.1 per cent of the more than 3.5 billion fans expected to tune in on TV and online streaming.

In addition, there are “intangible benefits”: mega-event hosting nations use the opportunity to demonstrate their ability to undertake complex projects, and build and/or promote their “brand name”. In turn the higher value brand name could attract foreign investment and increased international trade and tourism.

The other immediate benefit in hosting the World Cup is that the host nation automatically qualifies for the tournament (and Russia had a good run reaching the quarter finals), but it also has to include massive tax exemptions for the Fifa association and its corporate partners. Germany, for example, offered Fifa an estimated $272 million in tax exemptions when it hosted the 2006 World Cup.

Indeed, the biggest winner from the World Cup is not the host country or the winning team (which takes home the 18-carat gold trophy whose current market value is about $150,000, and $3m along with prestige and honour), but Fifa. Fifa has become “big business”: broadcasting rights for this year is expected to generate $3bn in revenue – a 25 per cent uptick compared to 2014’s $2.4bn. In addition, corporate sponsorships (mostly from Russia itself, China, and Qatar which is hosting the next World Cup) likely brought in a further $1.6bn in revenue, according to KPMG.

Heavy investment, short duration

Hosting international mega-events like a World Cup or a World Expo, such as the UAE’s Expo 2020, involve large capital outlays: stadiums, sports facilities have to be built, modernised or upgraded along with hotels and lodging for visitors and participants. Investments have to be made in transport and logistics to move millions of people: roads, trains, stations and airports have to be built or expanded to absorb the high intensity of use due to the influx of millions over short periods.

In addition, there are the increasing and non-recapturable security costs. Russia’s World Cup 2018 declared bill of $14.2bn, is one of the highest spend so far (somewhat lower than Brazil’s $15bn) with most of the money invested in infrastructure ($6.1bn), stadium construction ($3.4bn) and transport ($680m) – and compares to a spending of $10bn or more by nations that hosted the previous editions of the event.

The Oxford Olympics Study 2016 found that direct sports-related costs for the summer games since 1960 are on average $5.2bn and for the winter games $3.1bnn. But these costs exclude the wider infrastructure costs like roads, urban rail and airports, which often cost as much or more than the sports-related costs.

The most expensive summer Olympics was Beijing at $40-44bn and the massively expensive winter games of Sochi 2014 at $51bn. As of 2016, costs per participating athlete are on average $599,000 for the summer games and $1.3m for the winter event, which are higher given the smaller number of events and participating athletes. For London 2012, cost per athlete was $1.4m; for Sochi 2014, $7.9m.

Costs and benefits of mega events

The common characteristic of mega international events is that the investments are designed for a specific purpose and for a “limited duration” – running from several weeks for the World Cup or Olympics to six months in the case of World Expos. Historical evidence points towards large budget overruns: over the past 50 plus years, Olympic Games have gone over-budget by 179 per cent on average.

The bottom line is that the short-term benefits from the host country’s share of the event, tourism revenues and increased consumption are far outweighed by the heavy costs of event-related investments. In addition, there is an opportunity cost: mega-project investments are likely to crowd out spending towards health, education, social development, and in some cases, basic infrastructure (India’s embarrassing experience with the 2010 commonwealth Games comes to mind). Unless the economics change and there is revenue sharing from media and related property rights, it typically does not pay to host a mega-event, despite prestige and the higher value brand name.

Some lessons on hosting mega-events

What are the lessons from experience for countries and cities planning to host a World Cup or other mega-event? One, use and upgrade existing facilities. Two, focus on the legacy: what will become of the new facilities post-event? How will they be used to avoid white camels? Three, focus on and build lasting economic linkages between the event and the domestic economy. Four, sport is increasingly digital. Negotiate a share of the global media (TV and online) and IP rights with the organisers.

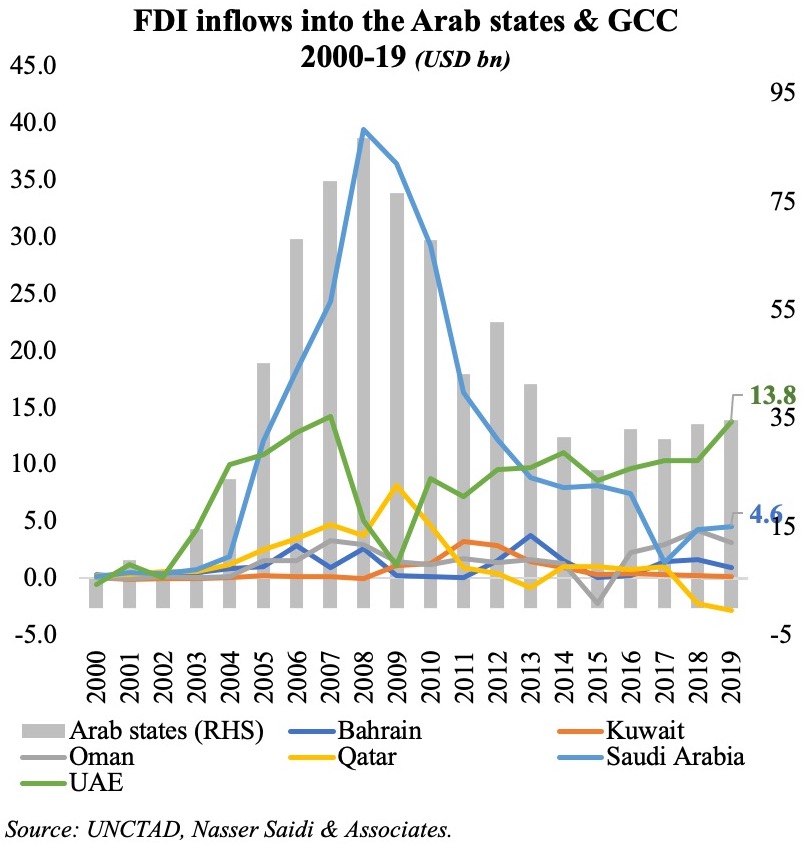

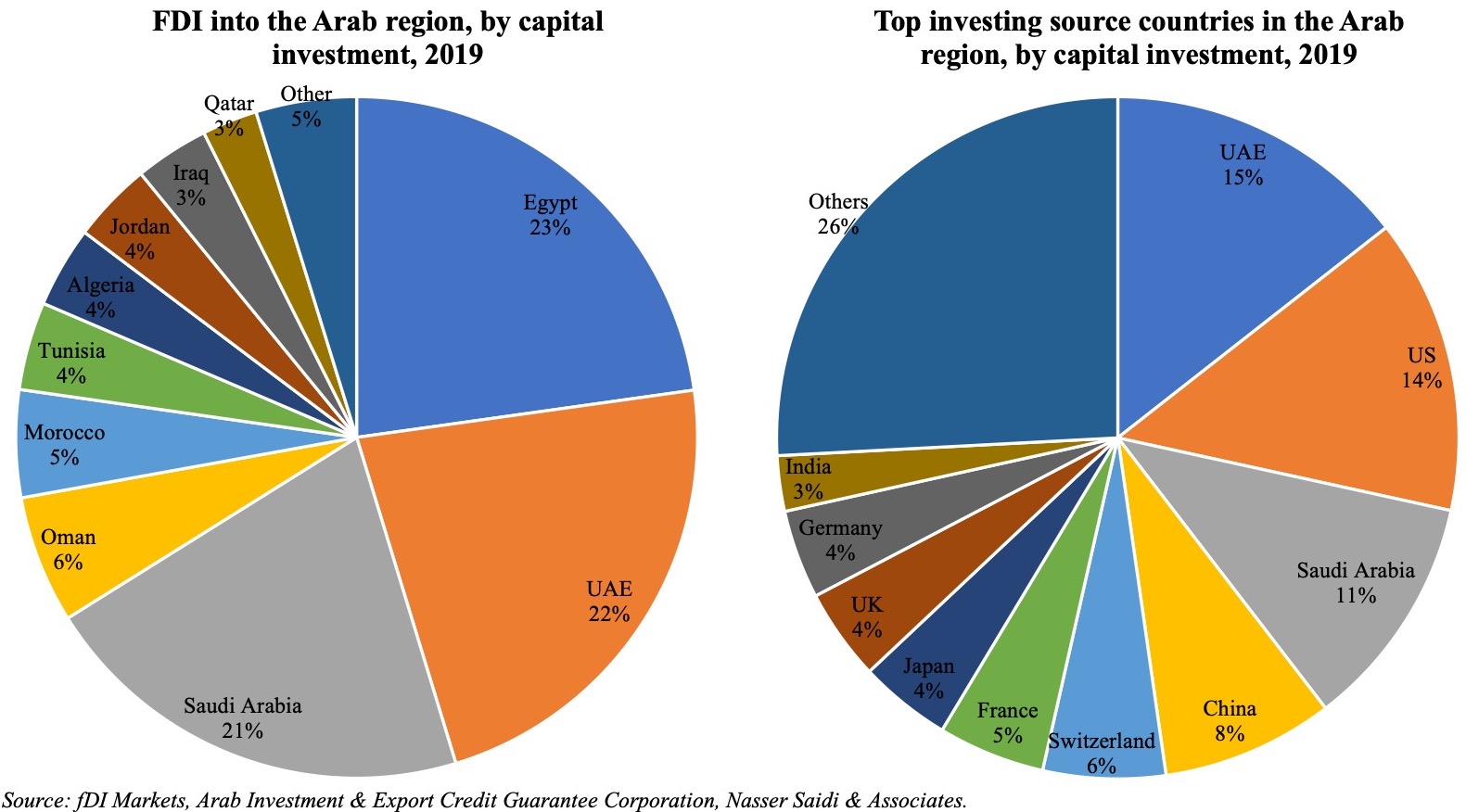

We focus on FDI in this Weekly Insight piece. FDI inflows are essential to the UAE’s diversification efforts, as it would not only create jobs, raise productivity and growth, but could also lead to transfer of technology/ technical know-how and promote competition in the market. According to the IMF, closing FDI gaps in the GCC could raise real non-oil GDP per capita growth by as much as 1 percentage point.

We focus on FDI in this Weekly Insight piece. FDI inflows are essential to the UAE’s diversification efforts, as it would not only create jobs, raise productivity and growth, but could also lead to transfer of technology/ technical know-how and promote competition in the market. According to the IMF, closing FDI gaps in the GCC could raise real non-oil GDP per capita growth by as much as 1 percentage point.

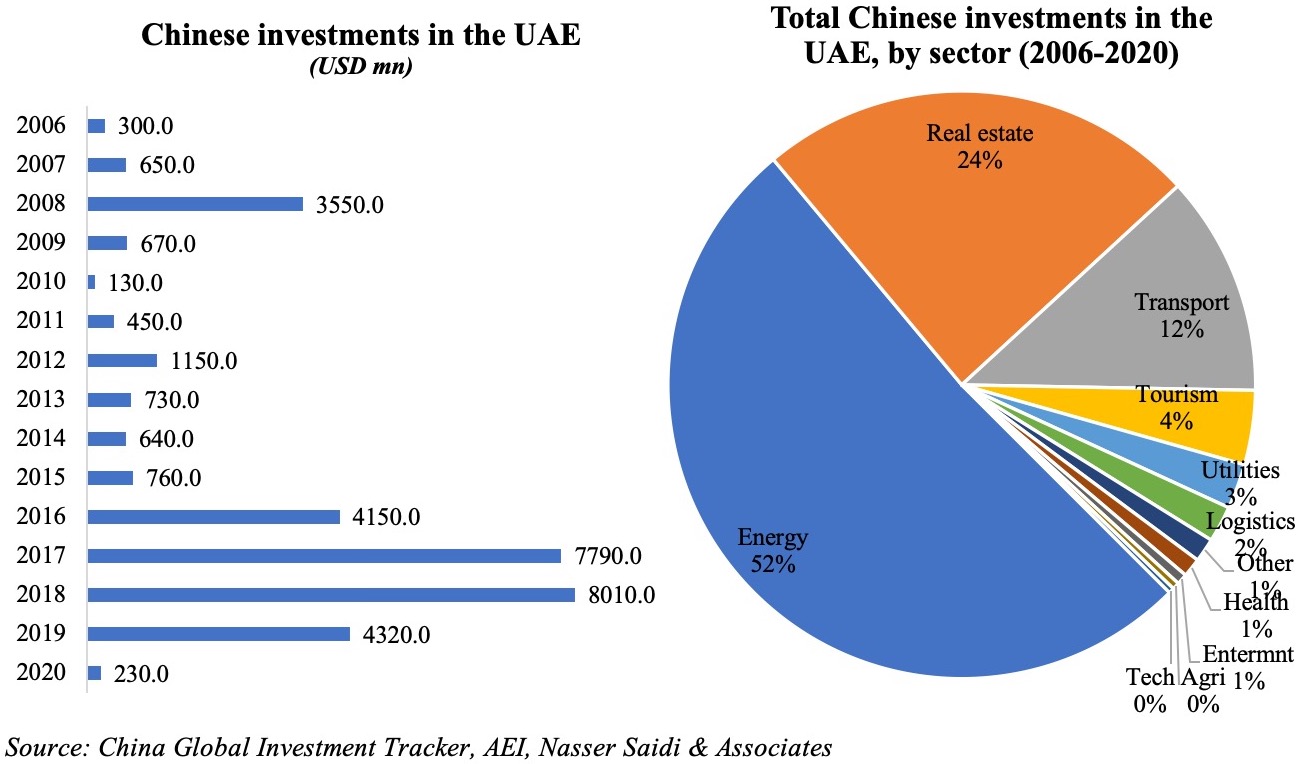

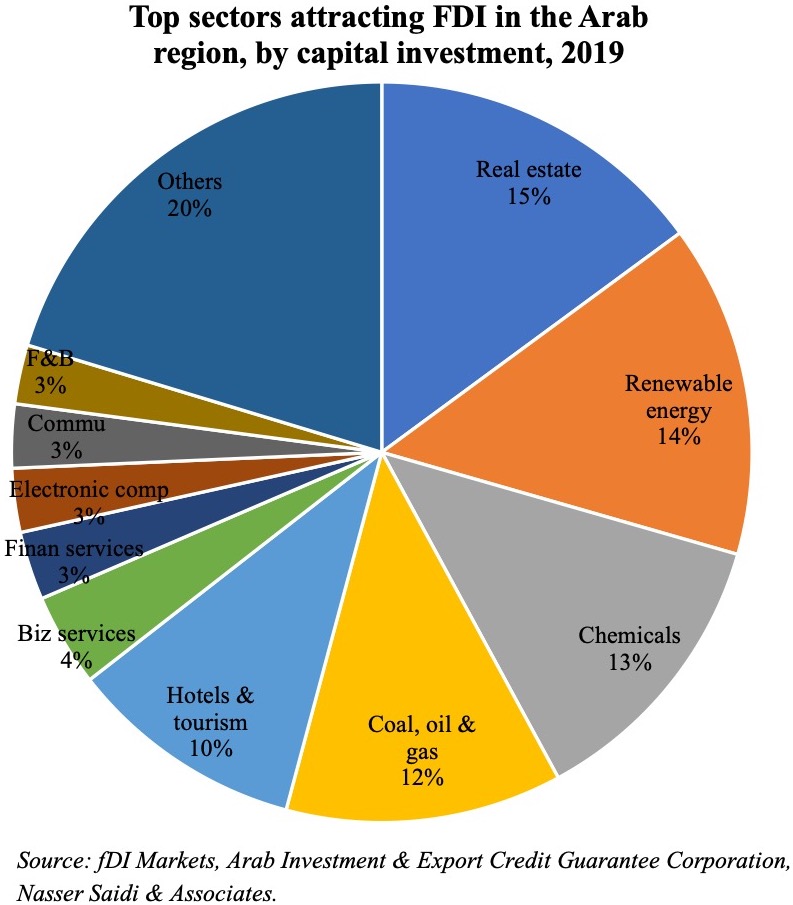

hinese projects tracked during Jan 2003-Mar 2020 (with the number of projects in double-digits in 2018 and 2019). According to AEI’s China Global Investment Tracker, the value of Chinese investments touched a high of USD 8bn in 2018, thanks to a handful of large projects (including with ACWA Power and Abu Dhabi Oil). Sector-wise, investments were concentrated in energy (both oil and gas as well as renewables), real estate and transport – together accounting for 87.8% of total investments during 2016-2020. This is largely in line with FDI inflows into the Arab region as well, with the top 5 sectors (real estate, renewables, chemicals, oil & gas and travel & tourism) accounting for close to two-thirds of total inflows in 2019.

hinese projects tracked during Jan 2003-Mar 2020 (with the number of projects in double-digits in 2018 and 2019). According to AEI’s China Global Investment Tracker, the value of Chinese investments touched a high of USD 8bn in 2018, thanks to a handful of large projects (including with ACWA Power and Abu Dhabi Oil). Sector-wise, investments were concentrated in energy (both oil and gas as well as renewables), real estate and transport – together accounting for 87.8% of total investments during 2016-2020. This is largely in line with FDI inflows into the Arab region as well, with the top 5 sectors (real estate, renewables, chemicals, oil & gas and travel & tourism) accounting for close to two-thirds of total inflows in 2019.