How to save Lebanon from looming hyperinflation, Article in The National, 31 Jul 2020

The article titled “How to save Lebanon from looming hyperinflation” was published in The National on 31st Jul 2020. The original article can be accessed here & is also posted below.

How to save Lebanon from looming hyperinflation

To bring the country’s economic chaos to an end, it is important to examine how it all began

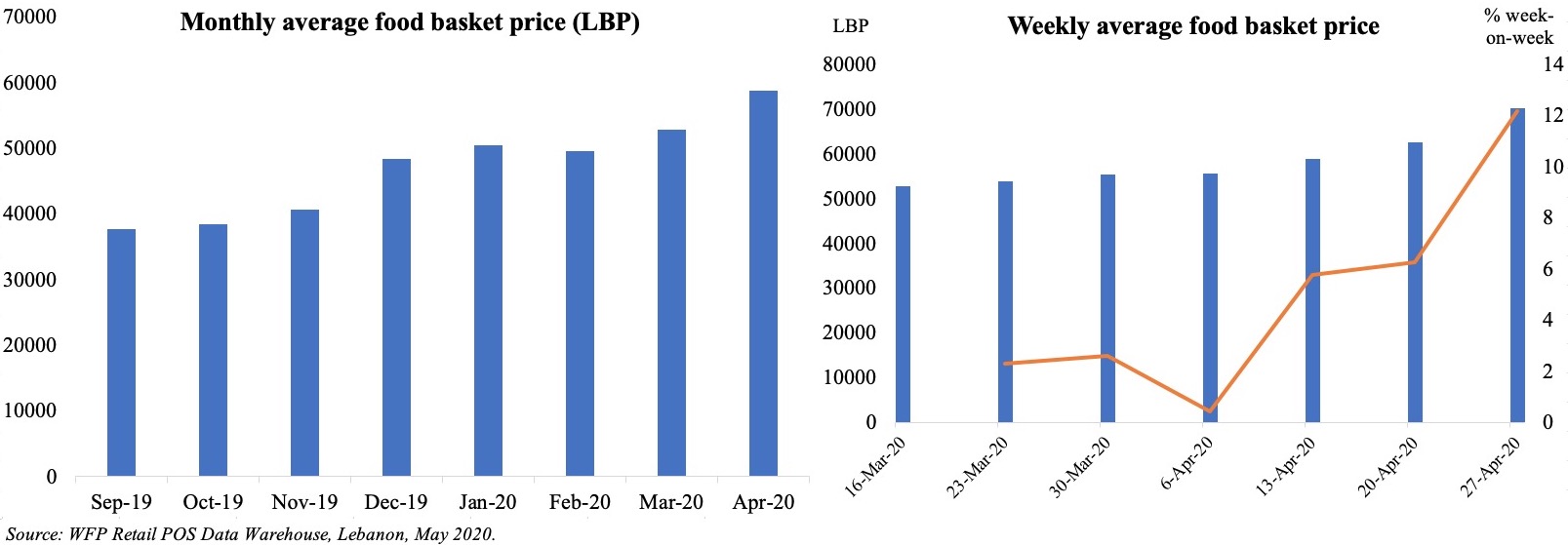

In June 2020, Lebanon’s inflation rate was 20 per cent, month-on-month. In other words, prices in the country were, on average, 20 per cent more than they were a month before. Compared to a year earlier, in June 2019, they had nearly doubled.

Lebanon is well on its way to hyperinflation – when prices of goods and services change daily, and rise by more than 50 per cent in a month.

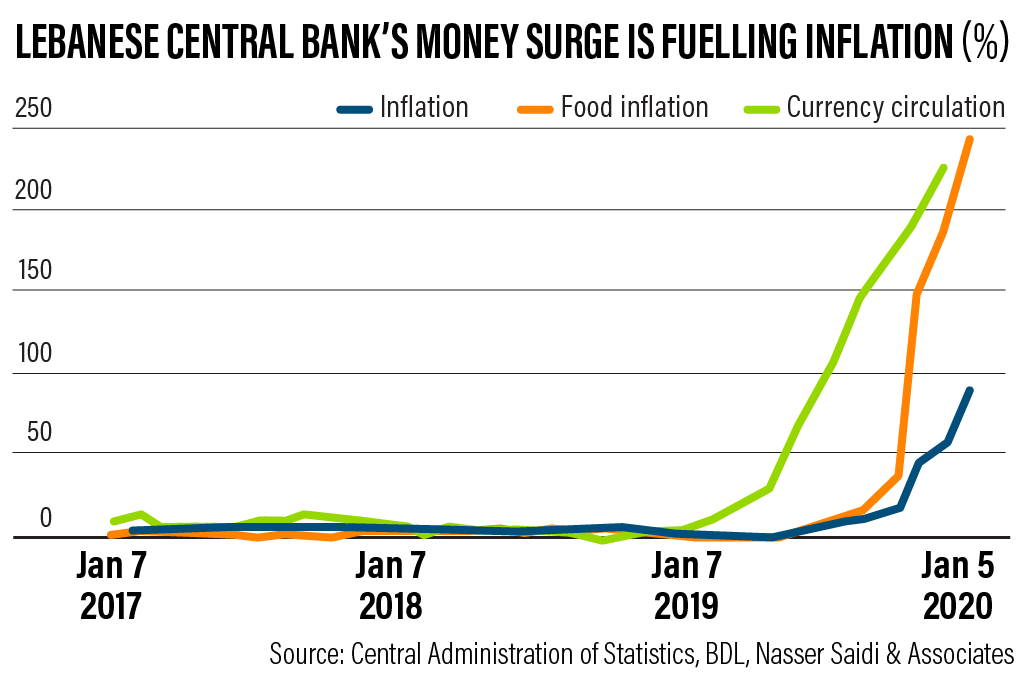

Hyperinflation is most commonly associated with countries like Venezuela and Zimbabwe, which this year have seen annual inflation rates of 15,000 per cent and 319 per cent, respectively. Lebanon is set to join their league; food inflation surged by 108.9 per cent during the first half of 2020.

When hyperinflation takes hold, consumers start to behave in very unusual ways. Goods are stockpiled, leading to increased shortages. As the money in someone’s pocket loses its worth, people start to barter for goods.

What characterises countries with high inflation and hyperinflation? They have a sharp acceleration in growth of the money supply in order to finance unsustainable overspending; high levels of government debt; political instability; restrictions on payments and other transactions and a rapid breakdown in socio-economic conditions and the rule of law. Usually, these traits are associated with endemic corruption.

Lebanon fulfils all of the conditions. Absent immediate economic and financial reforms, the country is heading to hyperinflation and a further collapse of its currency.

How and why did this happen?

Lebanon is in the throes of an accelerating meltdown. Unsustainable economic policies and an overvalued exchange rate pegged to the US dollar have led to persistent deficits. Consequently, public debt in 2020 is more than 184 per cent of GDP – the third highest ratio in the world.

The trigger to the banking and financial crisis was a series of policy errors starting with an unwarranted closure of banks in October 2019, supposedly in connection with political protests against government ineffectiveness and corruption. Never before – whether in the darkest hours of Lebanon’s civil war (1975-1990), during Israeli invasions or other political turmoil – have banks been closed or payments suspended.

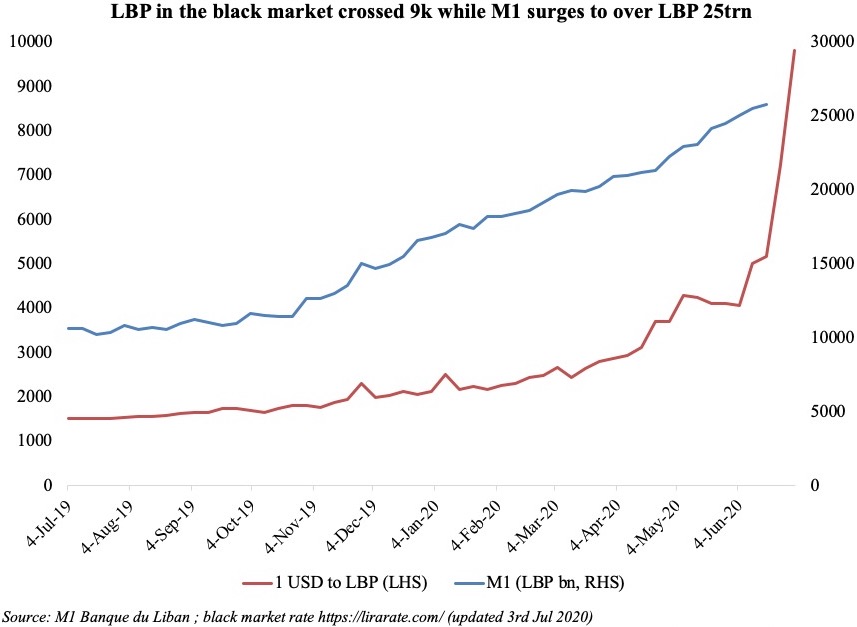

The bank closures led to an immediate loss of trust in the entire banking system. They were accompanied by informal controls on foreign currency transactions, foreign exchange licensing, the freezing of deposits and other payment restrictions to protect the dwindling reserves of Lebanon’s central bank. All of this generated a sharp liquidity and credit squeeze and the emergence of a system of multiple exchange rates, resulting in a further loss of confidence in the monetary system and the Lebanese pound.

Multiple exchange rates are particularly nefarious. They create distortions in markets, encourage rent seeking (when someone gains wealth without producing real value) and create new opportunities for cronyism and corruption. Compounded by the Covid-19 lockdown, the result has been a sharp 20 per cent contraction in economic activity, consumption and investment and surging bankruptcies. Lebanon is experiencing rapidly rising unemployment (over 35 per cent) and poverty rates exceeding 50 per cent of the population.

With government revenues declining, growing budget deficits are increasingly financed by the Lebanese central bank (BDL), leading to the accelerating inflation. The next phase will be a cost-of-living adjustment for the public sector, more monetary financing and inflation: an impoverishing vicious circle!

We are witnessing the bursting of a Ponzi scheme engineered by the BDL, starting in 2016 with a massive bailout of the banks, equivalent to about 12.6 per cent of GDP. To protect an overvalued pound and finance the government, the BDL started borrowing at ever-higher interest rates, through so-called “financial engineering” schemes. These evolved into a cycle of additional borrowing to pay maturing debt and debt service, until confidence evaporated and reserves were exhausted.

By 2020, the BDL was unable to honour its foreign currency obligations and Lebanon defaulted on its March 2020 Eurobond, seeking to restructure its domestic and foreign debt. The resulting losses of the BDL exceeded $50 billion, equivalent to the entire country’s GDP that year. It was a historically unprecedented loss by any central bank in the world.

With the core of the banking system, the BDL, unable to repay banks’ deposits, the banks froze payments to depositors. The banking and financial system imploded.

As part of Lebanon’s negotiations with the IMF to resolve the situation, the government of Prime Minister Hassan Diab prepared a financial recovery plan that comprises fiscal, banking and structural reforms. However, despite the deep and multiple crises, there has been no attempt at fiscal or monetary reform.

In effect, Mr Diab’s government and Riad Salameh, the head of the central bank, are deliberately implementing a policy of imposing an inflation tax and an illegal “Lirafication”: a forced conversion of foreign currency deposits into Lebanese pounds in order to achieve internal real deflation.

The objective is to impose a ‘domestic solution’ and preclude an IMF programme and associated reforms. The inflation tax and Lirafication reduce real incomes and financial wealth. The sharp reduction in real income and the sharp depreciation of the pound are leading to a massive contraction of imports, reducing the current account deficit to protect the remaining international reserves. Lebanon is being sacrificed to a failed exchange rate and incompetent monetary and government policies.

What policy measures can be implemented to rescue Lebanon? Taming inflation and exchange rate collapse requires a credible, sustainable macroeconomic policy anchor to reduce the prevailing extreme policy uncertainty.

Here are four measures that would help:

First, a “Capital Control Act” should be passed immediately, replacing the informal controls in place since October 2019 with more transparent and effective controls to stem the continuing outflow of capital and help stabilise the exchange rate. This would restore a modicum of confidence in the monetary systems and the rule of law, as well as the flow of capital and remittances.

Second is fiscal reform. It is time to bite the bullet and eliminate wasteful public spending. Start by reform of the power sector and raising the prices of subsidised commodities and services, like fuel and electricity. This would also stop smuggling of fuel and other goods into sanctions-laden Syria, which is draining Lebanon’s reserves. Subsidies should be cut in conjunction with the establishment of a social safety net and targeted aid.

These immediate reforms should be followed by broader measures including improving revenue collection, reforming public procurement (a major source of corruption), creating a “National Wealth Fund” to incorporate and reform state commercial assets, reducing the bloated size of the public sector, reforming public pension schemes and introducing a credible fiscal rule.

Third, unify exchange rates and move a to flexible exchange rate regime. The failed exchange rate regime has contributed to large current account deficits, hurt export-oriented sectors, and forced the central bank to maintain high interest rates leading to a crowding-out of the private sector. Monetary policy stability also requires that the BDL should be restructured and stop financing government deficits and wasteful and expensive quasi-fiscal operations, such as subsidising real estate investment.

Fourth, accelerate negotiations with the IMF and agree to a programme that sets wide-ranging conditions on policy reform. Absent an IMF programme, the international community, the GCC, EU and other countries that have assisted Lebanon previously will not come to its rescue.

Lebanon is at the edge of the abyss. Absent deep and immediate policy reforms, it is heading for a lost decade, with mass migration, social and political unrest and violence. If nothing is done, it will become “Libazuela”.

Nasser Saidi is a former Lebanese economy minister and first vice-governor of the Central Bank of Lebanon