Interview on Lebanon, hyperinflation & the way forward, TRENDS magazine, 5 Sep 2021

An interview with Dr. Nasser Saidi was published in the article titled “Hyperinflation imminent in Lebanon”, in TRENDS magazine dated 5th Sep 2021.

Excerpts from the conversation are posted below; the entire article can be accessed here.

In an exclusive interview with TRENDS, Dr Nasser H. Saidi — former Minister of Economy and Trade and Minister of Industry of Lebanon between 1998 and 2000 and the first Vice-Governor of the Central Bank of Lebanon for two successive mandates, 1993-1998 and 1998-2003 — describes the present Lebanon’s economic crisis as “one of the most massive depressions in Lebanese history”.

Dr Saidi, who is also Founder and President of Nasser Saidi & Associates and Former Chief Economist and Head of External Relations at the DIFC Authority, said that Lebanon got here because of multiple crises occurring at the same moment. However, the primary issue was non-sustainable indebtedness, both government and central bank debt, as well as an increasingly unsustainable balance of payments and an inflated value of the Lebanese pounds. These factors have contributed to the current crisis in Lebanon.

He claimed that the government’s borrowing was not used to fund the construction of real assets or infrastructure. The Central Bank, on the other hand, was borrowing to defend an overvalued Lebanese pound, so it had to pay high interest; this was referred to as financial engineering, but it was a like “Ponzi scheme.”

How far will Lebanon’s inflation fly?

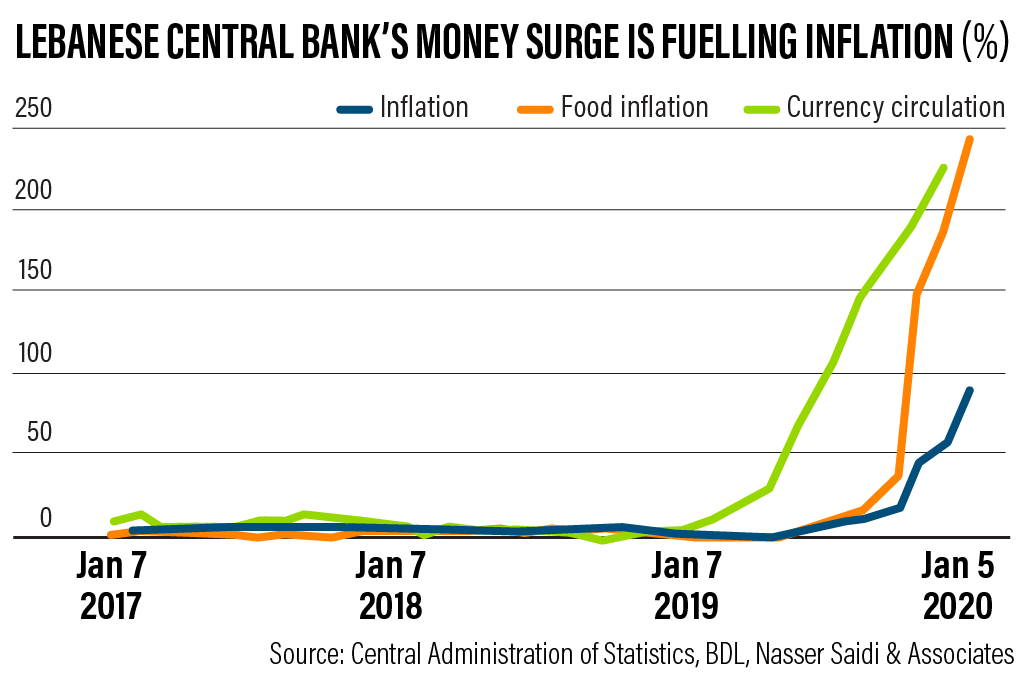

The Lebanese economy, according to Saidi, is heavily dollarized, which means Lebanon imports a lot of commodities and the currency rate plays a big role in goods and services. As a result of the collapse of the financial exchange rate system, prices began to rise. Furthermore, the Lebanese Central Bank continued to fund the government’s deficit, which means infusing more money into the system, resulting in higher inflation rates.

“As a result, we are on the edge of hyperinflation unless the government implements significant deep reforms, such as fundamental, monetary, fiscal, and structural reforms,” he said.

Saidi felt that the Lebanese government and Central Bank should issue a new currency, a new lira, and cancel the old currency. “This is because we are on the verge of hyperinflation, with monthly price increases of 25 percent, because of cost adjustments that the government is willing to take,” he pointed out.

Recovery takes time

According to Saidi, predicting when Lebanon would emerge again is difficult since it depends on whether changes are implemented, whether a credible government is in place to implement these reforms, and whether Parliament passes the necessary legislation.

He believes that if the Lebanese government started a program right now, it would take Lebanon 5-7 years to re-emerge. However, poverty and unemployment will persist, and it will take a long time to return to Lebanon’s productive levels.

Saidi went on to say that Lebanon needed to confront the humanitarian issue and begin the reform process. As a result, it might require around US$1.5bn, which we could raise through humanitarian aid meetings, the World Bank, Gulf countries, the EU, and other well-donors.

Reasons for banking crisis

The banking sector is illiquid and insolvent, but, according to Saidi, the reason for its insolvency is that the banks lent money to the Central Bank, which then used those deposits to finance the government and defend the Lebanese lira. As a result, the central bank suffered massive losses of more than US$60bn.

By the end of 2019, the banking sector had invested over 75 percent of its assets in the Central Bank, government treasury bills, and Eurobonds. The Lebanese Eurobond is now being sold for 12 cents on the dollar, meaning it has lost 88 percent of its value.

This means that the banks’ holdings, including their holdings of Central Bank, secured certificates of deposits, and bonds, have also been reduced, resulting in massive losses.

Saidi believes that Lebanon’s banking sector, before the crisis, was too big for the size of the economy. Hence the government must reduce the size by at least 50 percent, if not more, which means a total restructuring of the banking sector.

He also added that the Lebanese banks now require an equity injection and must sell some of their assets abroad, which some banks have started so.

The banking system has failed, and there is no longer trust in the financial sector. The Central Bank had a significant role in the failure because of the fixed exchange policy and the government’s continuous financing, he said.

Regaining the customers’ trust

To regain the customer’s trust, the banks should recapitalize, which requires a large injection of around US$20bn from the bank’s shareholders.

According to Saidi, bank bailouts are necessary. Still, they must be followed by a plan to stabilize the economy, such as fiscal and structural changes companies with international aid and financing from the IMF, World Bank, EU, and of course, the GCC countries.