How should GCC economies manage public finances, Opinion Piece in Gulf Business, Nov 2021

This article appeared in Gulf Business online on 1st Nov 2021, and can be accessed online.

How should GCC economies manage public finances

Governments can use sovereign asset liability management as a financial tool to manage public sector balance sheet risks

The Cop26 climate talks in November 2021 will confirm global commitments to counter climate change and move to a sustainable future.

At the core of the response is the energy transition away from hydrocarbons, the main source of wealth for GCC countries. While there is much focus on the energy system transition, part of the challenge for GCC countries is how they will manage their wealth and public sectors, assets and liabilities — much of which depend on hydrocarbons. That will require efficient public fiscal and financial management to ensure sustainability through a tool known as Sovereign Asset Liability Management (SALM).

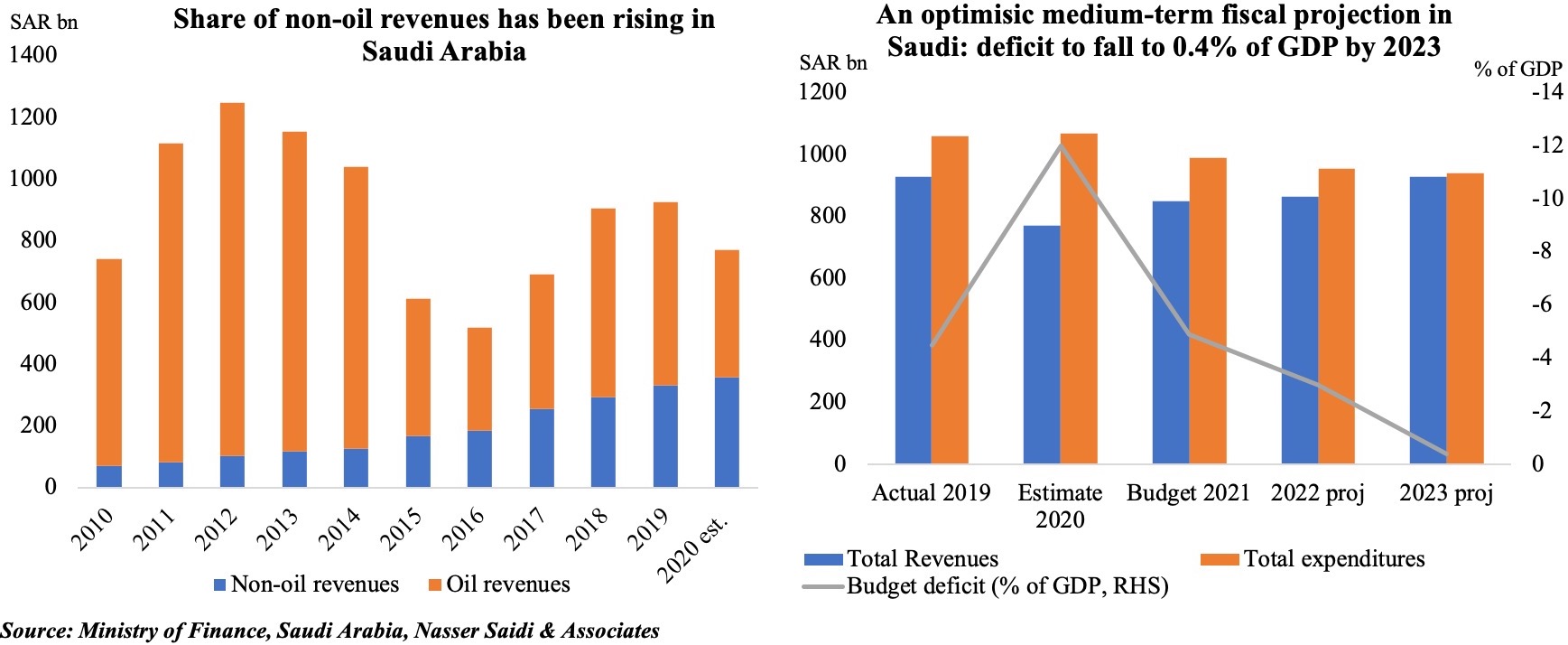

At present, GCC governments run large non-hydrocarbon fiscal deficits despite major initiatives in recent decades to diversify their economies.

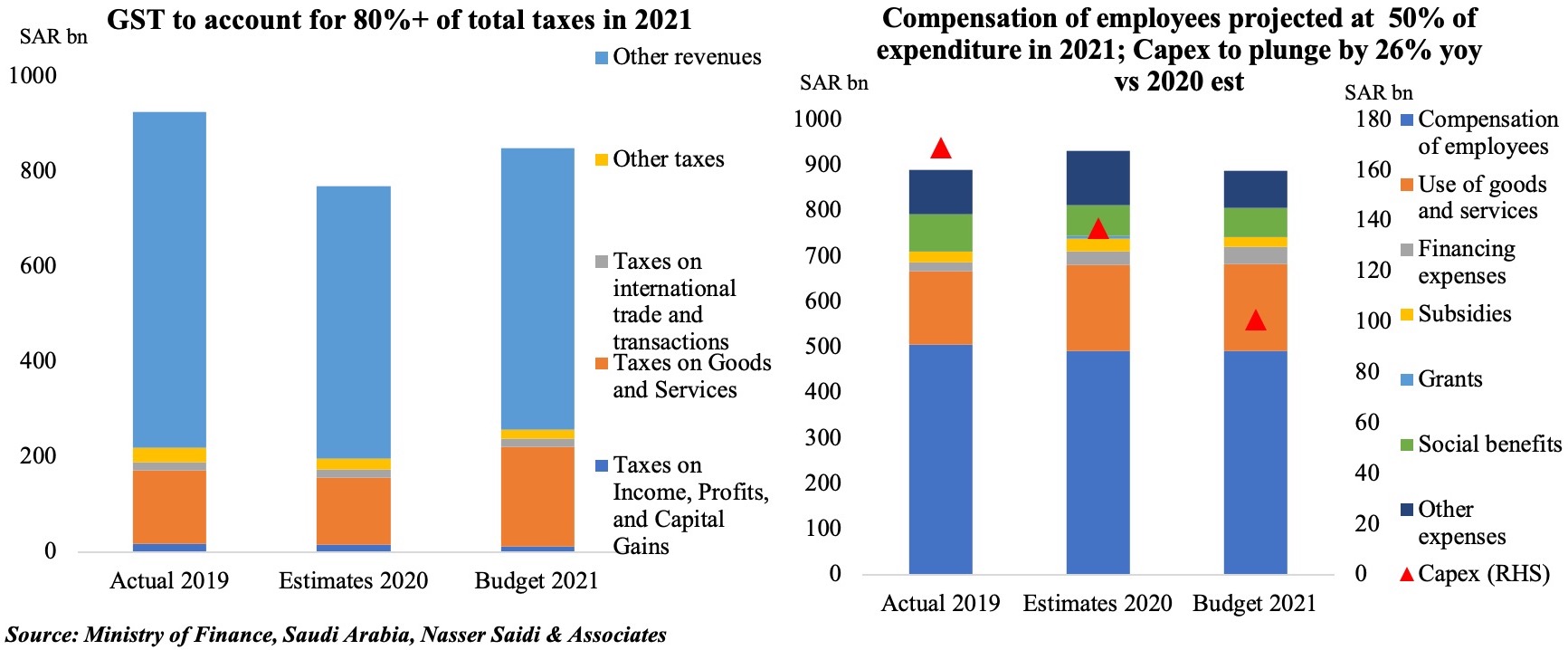

Governments have set up economic zones, infrastructure investments, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and government-related entities (GREs). They have moved some public finances away from hydrocarbons through reforms to subsidies, public utilities pricing, and expenditures, along with the introduction of value-added tax. Despite these changes, the non-hydrocarbon primary balance as percent of non-oil GDP remains negative for all GCC countries.

Along with the fiscal dependence on hydrocarbons, GCC governments have future liabilities.

On the positive side of the ledger, decades of rapid economic growth have resulted in the accumulation of large international reserves and financial investments, a build-up of real assets and companies.

At the same time there has also been an increase in debt, contingent liabilities, and generous social programmes that governments have to finance. Adding to that burden is the size and extensive role of state-owned entities (SOEs) and government-related entities (GREs) in GCC economies.

In some cases, the liabilities of SOEs and GREs are estimated to constitute over 30 per cent of GDP, which has an effect the overall soundness of public sector balance sheets.

Financing these liabilities could be difficult during the energy transition as it implies lower prices in real terms for oil and gas.

GCC countries run the risk of an earlier than expected depletion of their net financial wealth. Their hydrocarbons and associated industries could become stranded assets.

These countries could also find it difficult to draw upon their sovereign wealth funds, which have stabilised government accounts during times of volatile commodity prices. Asset accumulation in these funds flattened following the drop in oil prices end of 2014, leading to a drawdown in reserves.

Over the long-term, as the IMF has warned, the net financial wealth of GCC countries could turn negative by 2034, turning the region into a net borrower.

To manage these financial risks, GCC governments should adopt SALM to handle the financial aspects of the energy transition. This system integrates multiple public assets, future revenues, and cash reserves, along with public debt and contingent liabilities into one sovereign balance sheet. That allows governments to manage liquidity, risks, savings, and commitments, to ensure macro-fiscal stability and long-term sustainable public finances.

They will be able to manage resources more adroitly, leading to a smoother transition away from hydrocarbons.

Denmark and New Zealand, for example, have implemented a comprehensive SALM framework successfully. They have improved their risk, fiscal and debt management significantly. They have also ensured intergenerational equity so that future generations do not pay for today’s spending. Their finances are now more resilient to shocks, and there is greater efficiency in the use of government assets, quality in the provision of government services, and wealth management.

To implement SALM, GCC governments will need an effective governance framework. They should institute clear mandates for the different public sector entities so that their data is transparent and should encourage cooperation, centralisation of risk management, and market-oriented valuations of assets and liabilities.

They should start their SALM journey by identifying the assets and liabilities of the public sector. That means creating a full register of public assets, followed by the collection of data and the construction of a comprehensive balance sheet. Then, they should develop dynamic tools that connect to each other, allowing a complete overview. That means policy making decisions that are evidence-based, impactful, equitable, and those that minimise risk.

The result will be an effective policy making and leadership decision engine.

In essence, the public sector would emulate the sound financial management tools used by modern private corporations in managing their balance sheets and risks.

As GCC countries move away from hydrocarbons, they will need SALM as a macro-economic and financial tool. SALM will allow them to manage risks in the public sector balance sheet and decide on policy tradeoffs during the move toward a sustainable future, ensuring that future generations inherit sound public finances.

The article is written by Nasser Saidi & Talal F Salman

Nasser Saidi is an economist and former minister and Central Bank vice governor in Lebanon, and Talal F. Salman is a principal with Strategy&