Weekly Insights 11 Mar 2021: Will removing legal & regulatory barriers reduce MENA’s yawning gender gap?

Download a PDF copy of this week’s insight piece here.

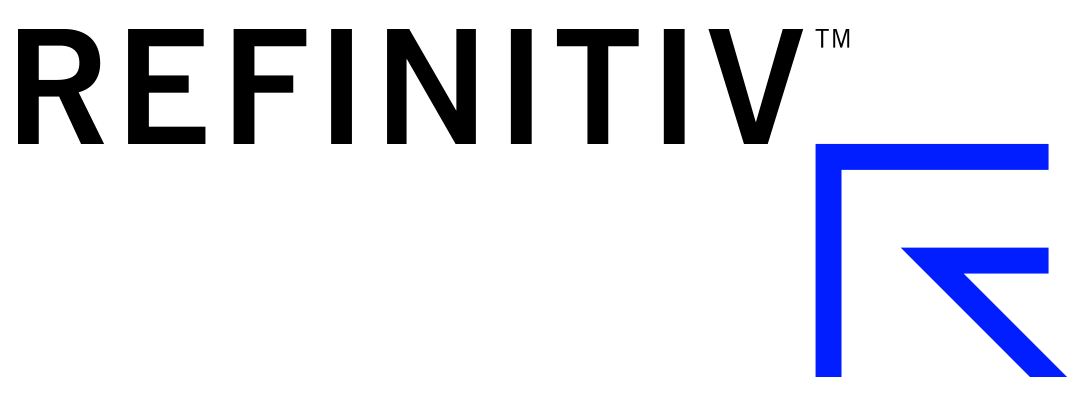

Chart 1. MENA & OECD high-income economies reformed the most in Women, Business & the Law Index 2021

- The latest edition of Women, Business and the Law found that economies in MENA reformed the most, posting an average score of 51.5 in 2021. Agreed, most started from a low base, have lot to catch up on and cross-country variations are the highest!

- Within the region, the lowest score is at 26.8 (West Bank & Gaza) and highest at 82.5 (UAE)

- WEF’s Global Gender Gap Index found that gender gap in MENA narrowed by 3.6 points b/n 2006 & 2019: assuming same progress rate, it will take approx. 150 years to close gender gap in MENA

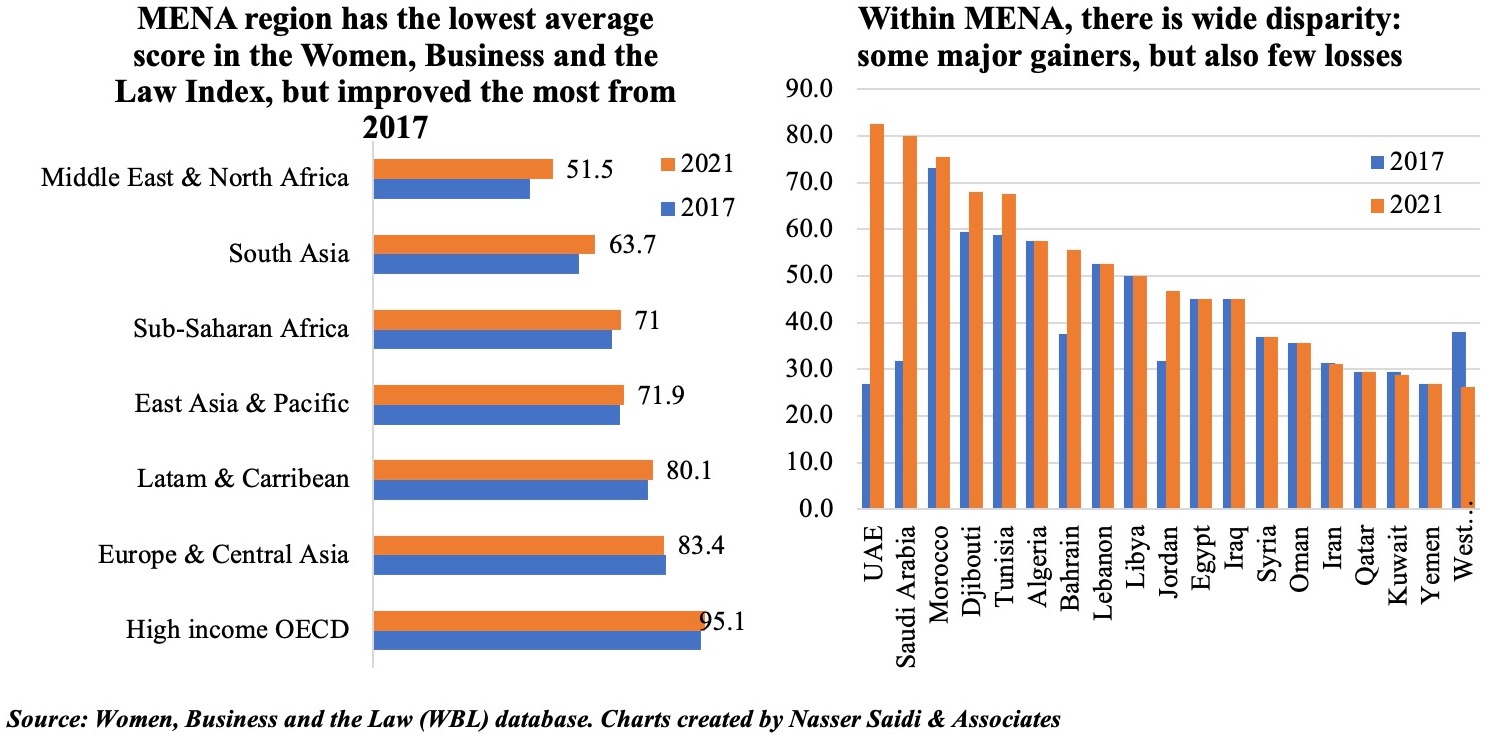

Chart 2. Removing Regulatory Barriers Is Only the Start: it’s a Long Way to Gender Parity!

- Consider the “best performing” regulatory aspects in MENA (from the table below):

- Entrepreneurship: 7 of the 19 nations score a perfect 100 and others 75;

- Mobility & workplace regulations should encourage women to enter the workforce;

- Does this translate into practice?

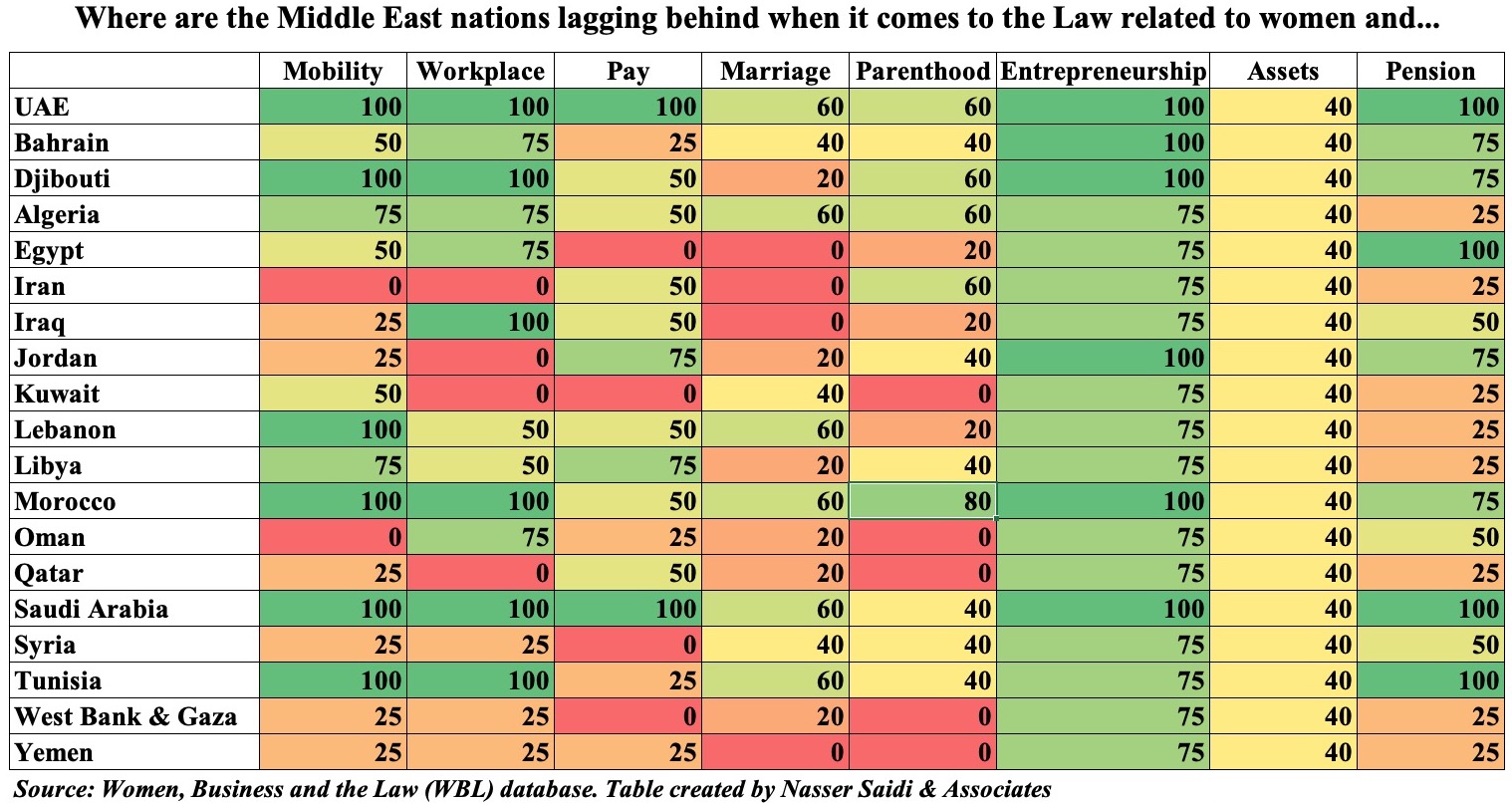

Chart 3. Have Better Regulations Supported Entry of More Women Entrepreneurs in MENA?

- Less than one-fifth of new limited liability company owners are women in the Middle East: ranges between a high of 21.5% in Bahrain to low of 6.9% and 8.8% in Algeria & UAE respectively

- Sole proprietorships are more frequently used by female entrepreneurs: but, evidence shows a wide disparity of women business owners relative to men. This male-female gap is the lowest in Morocco with share of women business owners (as sole proprietors) at 41% versus men at 59%

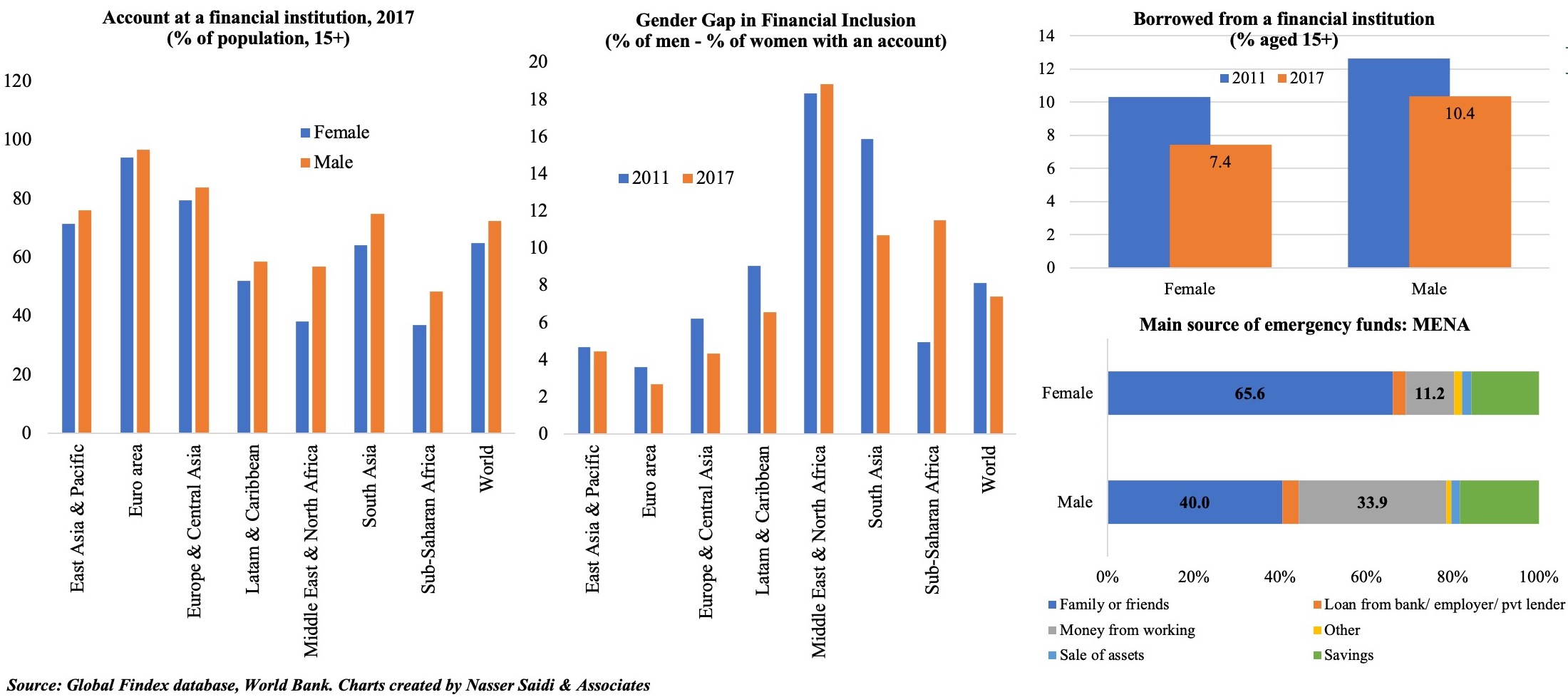

Chart 4. Access to Finance is a Major Barrier

- One of the biggest challenges when it comes to women entrepreneurs is access to finance

- Higher the access to bank accounts for women, the higher the share of female entrepreneurs;

- Higher the lending to women, the higher the share of female entrepreneurs

- MENA reported the largest access to finance gender gap of any region: 52% of men vs only 35% of women have an account; the gender gap in financial access increased between 2011 and 2017!

- Borrowing from a financial institution was low for both men and women in MENA: 10.4% and 7.4% respectively in 2017 (lower than in 2011). When in need of emergency funds, women raise money from friends & family (65%) than other sources

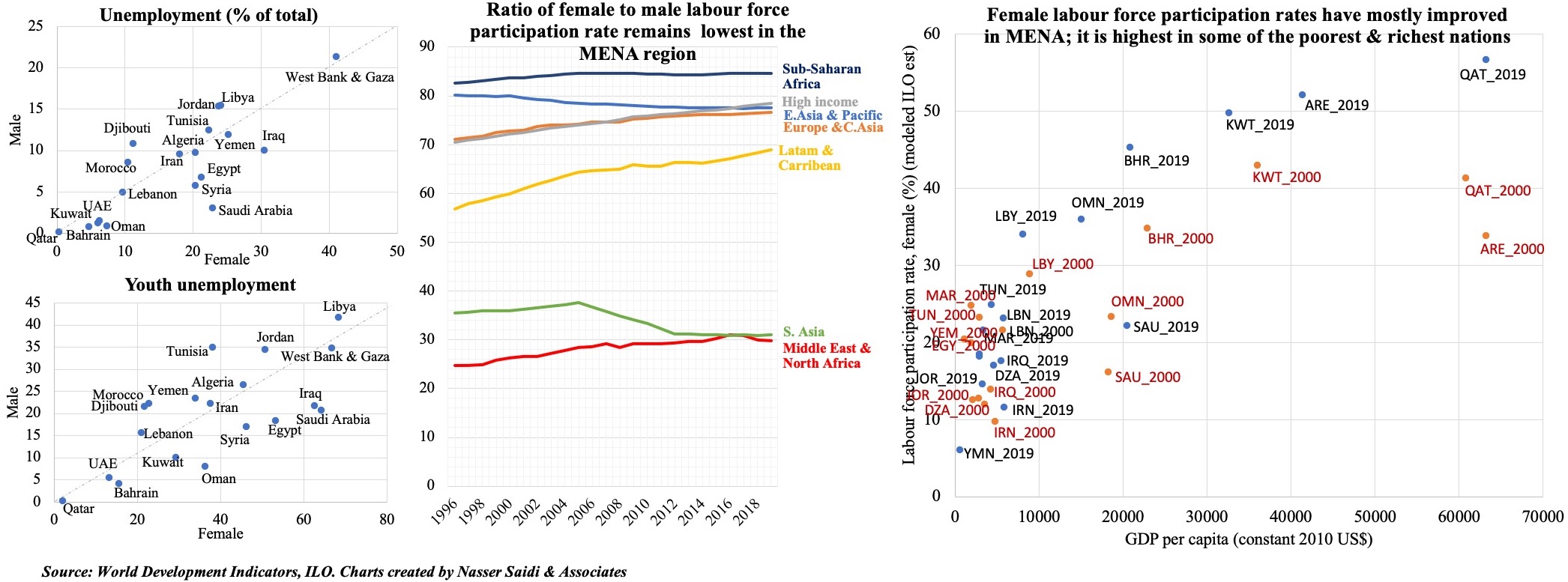

Chart 5. Gender Inequality in Labour Market Outcomes Persist in the MENA region

- Ratio of female to male labour force participation rates (LFPR) continue to be the lowest in MENA

- Large variations in Female LFPRs within MENA: as high as 56% in Qatar, 34% in Libya (low-income) to lows of 6% & 11% in Yemen and Iran respectively. In most cases, female LFPR is higher among single women than married (signalling the influence of cultural/ social norms)

- Even when women actively participate in the workforce, their share of employment in senior & middle management is small: 15.8% in the UAE, 19.3% in Tunisia, 19.8% in Iran and 28.9% in Lebanon (ILO)

- Despite relatively high levels of education, female unemployment is high in MENA & female youth unemployment even higher!

What can be done to support regulatory reform aiming for gender equality?

- Removing legal and regulatory barriers is necessary but not sufficient condition to reduce the yawning gender gap in the Middle East & North Africa region

- The IMF estimates that reducing the gender gap in labour force participation to double (rather than triple) the average for emerging market and developing economies would have doubled GDP growth in MENA over the past decade: a gain of USD 1trn in cumulative output

- Digital economy and labour market reforms (part-time, flexible work arrangements) will boost women’s overall participation

- Support for women entrepreneurs via: (a) access to finance (loan guarantees, grants, microfinance); (b) women-led networks (VC, angel investors) to invest in women-owned businesses; (c) a “sandbox” for texting new products/ concepts

- Encourage the collection of disaggregate data by gender by the private sector, share them with regulators for policymaking (e.g. share of females employed in senior & management levels, reason for leaving employment, banks’ loan portfolios etc.)