“Tariffs, Taco and Cepas: diverging trade paths in a fragmenting world”, Op-ed in Arabian Gulf Business Insight (AGBI), 17 July 2025

The opinion piece titled “Tariffs, Taco and Cepas: diverging trade paths in a fragmenting world” was published in Arabian Gulf Business Insight (AGBI) on 17th July 2025.

“Tariffs, Taco and Cepas: diverging trade paths in a fragmenting world”

On July 9 the 90-day tariff pause imposed by the Trump administration came to an end, reigniting global trade tensions.

Several countries now face a fresh wave of levies scheduled to take effect on August 1.

These include a 25 percent tariff on nations such as Japan and South Korea, both currently in trade negotiations with the US; 30 percent on the European Union, Mexico and South Africa; 35 percent on Canada; 40 percent on Laos and Myanmar and a steep 50 percent rate on Brazil.

In a broader escalation, the administration also threatened an additional 10 percent tariff on Brics nations should they pursue what it describes as an “anti-American” policy stance.

For many small, developing, export-orientated countries, the loss of access to US markets represents a major economic shock.

Adding to the pressure, a 50 percent tariff was announced on copper – a critical material used in everything from wiring and plumbing to clean energy and AI infrastructure.

Other sectors under consideration for new imposts include pharmaceuticals, semiconductors and lumber, potentially broadening the impact across global supply chains.

Unlike the April announcement, which triggered a stock market sell-off, last week’s developments barely ruffled investor sentiment.

Wall Street remains at record highs, and Nvidia reached a $4 trillion market cap milestone – suggesting markets view the threats as negotiating theatrics, summed up by the acronym Taco: Trump Always Chickens Out.

But this calm may prove premature. Markets could be underestimating the risk that rhetoric hardens into policy.

US protectionism, aimed at shielding domestic industries under the guise of national security, has proven disruptive. It has fractured supply chains, distorted trade and investment flows and injected global economic uncertainty, affecting far more than direct trade partners.

Policy volatility has surged to levels not seen since the pandemic, heightening uncertainty over monetary policy, debt and interest rates, given tariffs’ impact on inflation and growth. Tariffs act as a tax on imports, raising prices for both intermediate goods and consumer products.

The Fed is left with a dilemma: keep policy tight to fight inflation and risk stifling weak growth, or accommodate price shocks and face Trump’s attacks on the Fed chair for not cutting rates.

GCC nations were initially hit with a blanket 10 percent US tariff, with sectors like aluminium and steel facing duties of up to 25 percent. The latest list now imposes a 30 percent rate on Algeria, Iraq and Libya, and 25 percent on Tunisia.

A major focus is the transshipment of goods from China, an issue raised in the US-Vietnam trade agreement, which introduces a 20 percent general tariff and a 40 percent rate on transshipped goods. Yet the definition of “transshipment” remains vague: does it mean rerouting and repackaging, or include Chinese inputs?

For Gulf countries like the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Qatar, global logistics and re-export hubs, with deep trade ties to China and extensive special economic zones, the implications are serious. These states could face further tariff pressure unless they increase local value addition to ensure goods meet domestic origin criteria.

The UAE’s agreements with China to develop EV and solar glass manufacturing facilities mark strategically important steps toward localisation. This shift is increasingly essential, particularly as rules of origin pose major hurdles in trade talks, as seen in the ongoing US-India negotiations.

In contrast to US protectionism, the UAE has pursued a radically different path. By negotiating around 27 comprehensive economic partnership agreements (Cepas), it has positioned itself as a global model of trade and investment liberalisation.

These Cepas go well beyond traditional free trade deals, covering goods, services, digital trade and investment. They also address non-tariff barriers and standards, creating a seamless framework for global commerce.

Such deep trade agreements also drive investment and innovation. The UAE is a case in point: its non-oil foreign trade surged 19 percent year-on-year in Q1 to AED835 billion, far outpacing the global average of just 2-3 percent.

At this pace, the UAE is set to reach its AED4 trillion trade goal within two years – ahead of its 2031 target.

It has also emerged as a major FDI destination. Inbound investment rose 49 percent to $46 billion in 2024, ranking second globally for greenfield projects, behind only the US.

Beyond trade and investment, the UAE is attracting entrepreneurs, skilled professionals, including tech talent, and high-net-worth individuals, a testament to a stable, business-friendly ecosystem.

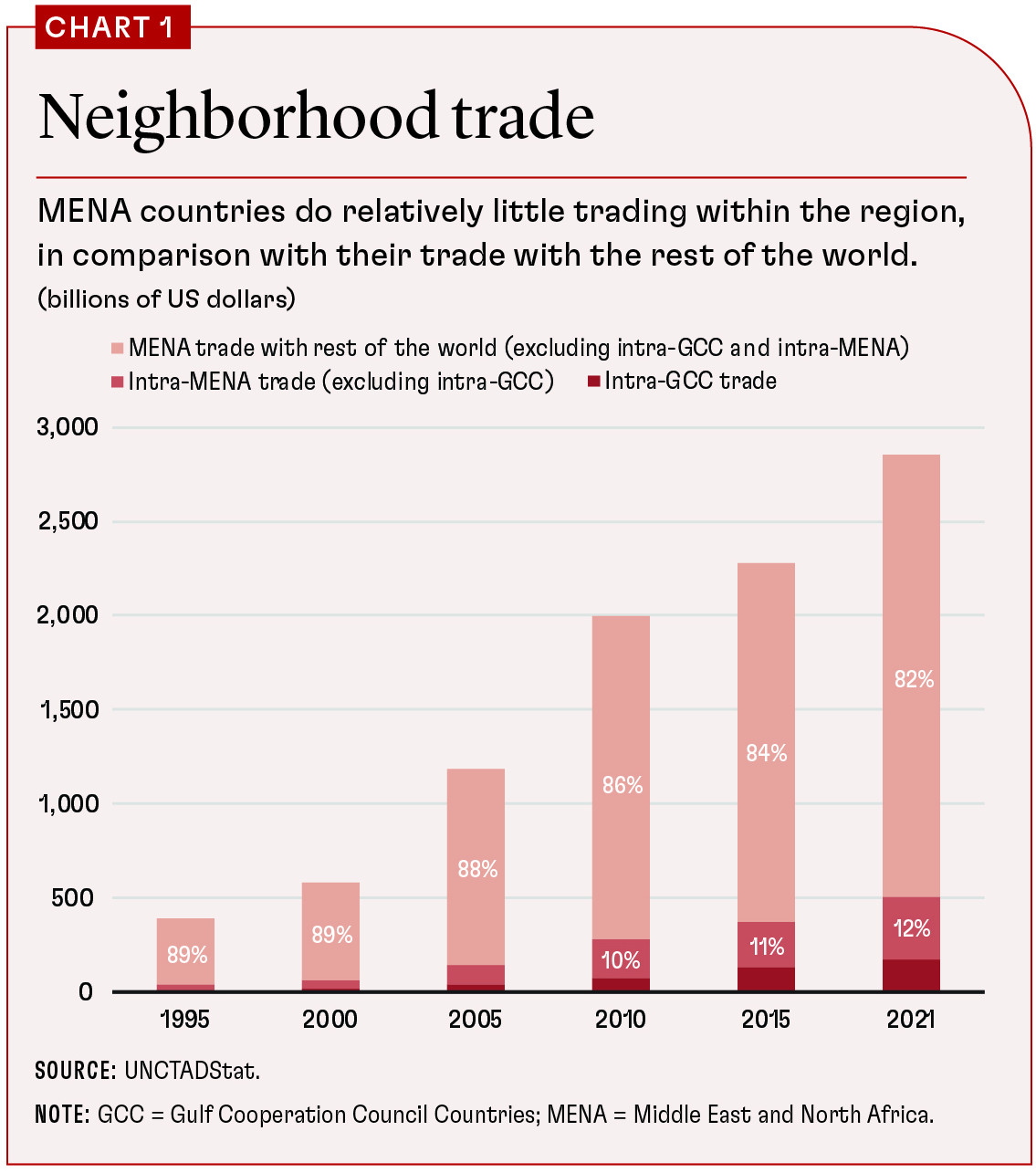

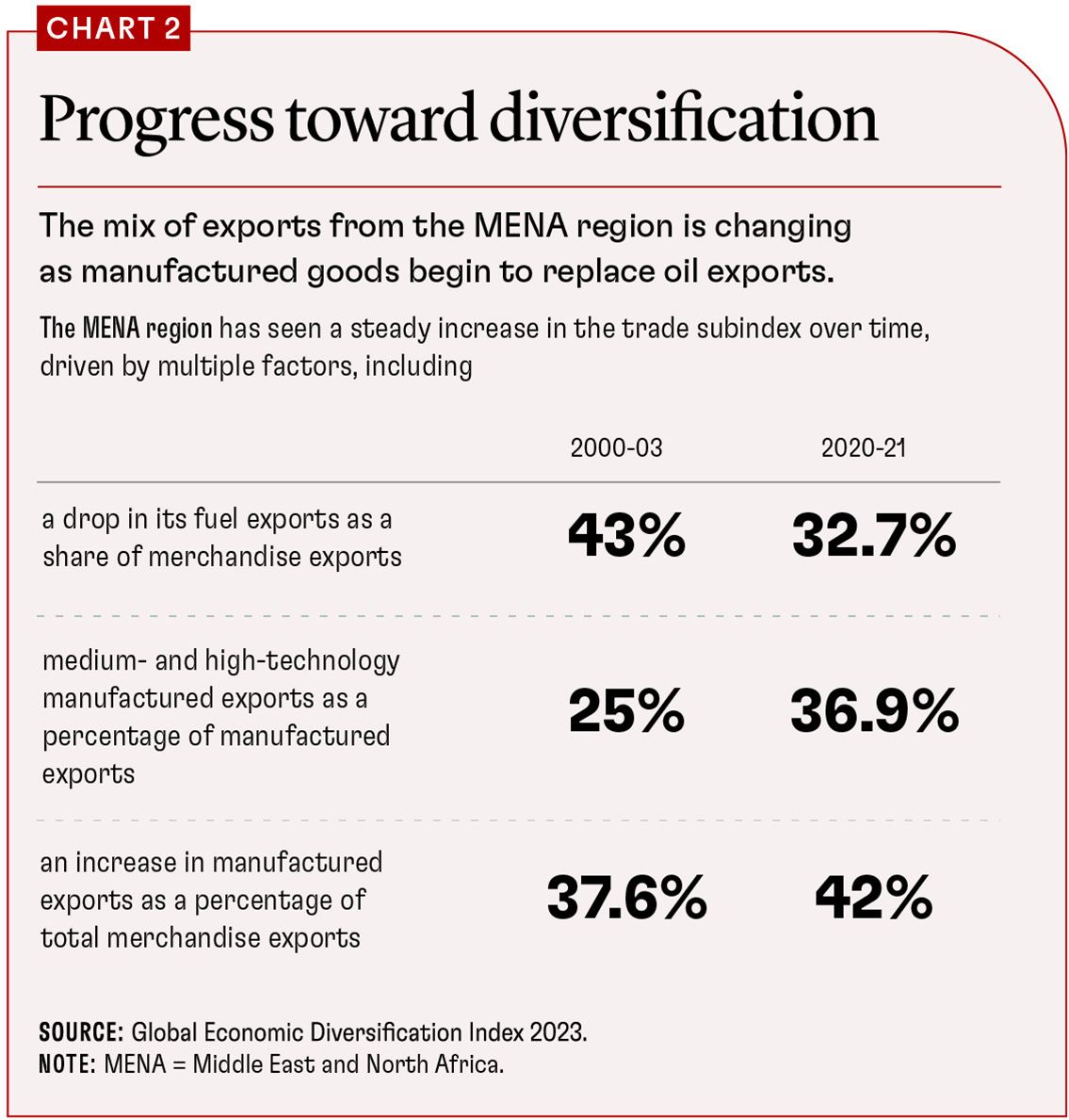

Trade remains a critical engine of economic growth. Cepas support not just liberalisation, but also economic diversification and modern industrial strategy.

For the GCC, these deals are forging resilient new corridors linking the Gulf with fast-growing Asian markets and the demographic powerhouse of Africa.

Combined with the region’s rapid tech adoption, from AI to green data centres and clean energy exports, Cepas can place the GCC on a more sustainable growth path.

In a world where political and economic fragmentation threatens prosperity, the UAE offers a compelling countermodel: strategic openness remains the most viable path to a resilient, high-growth economy.

Dr Nasser Saidi is the president of Nasser Saidi and Associates. He was formerly chief economist and head of external relations at the DIFC Authority, Lebanon’s economy minister and a vice governor of the Central Bank of Lebanon

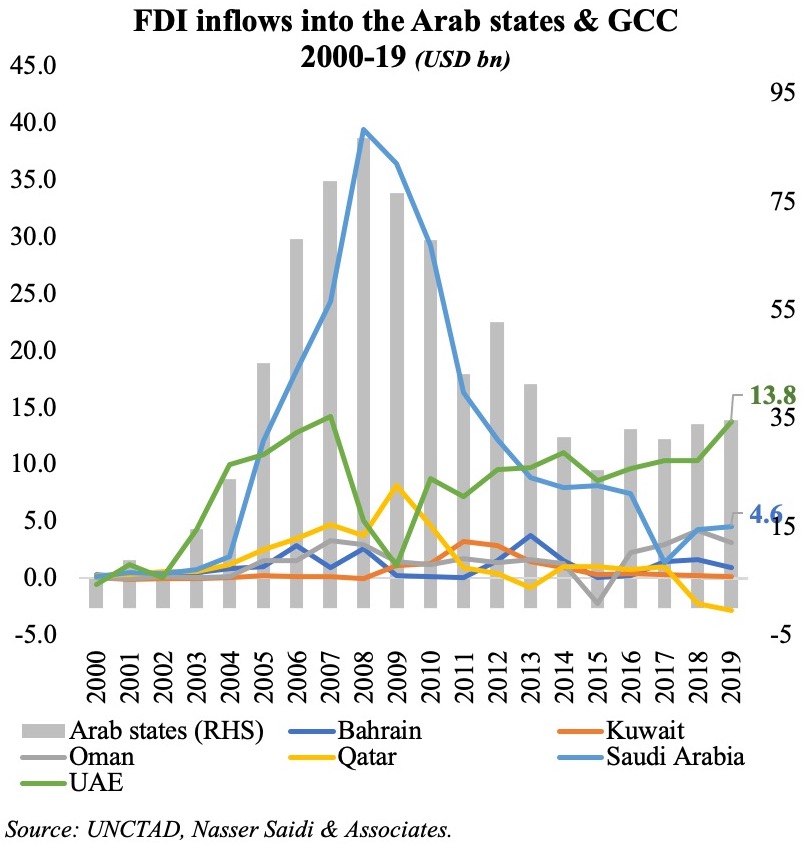

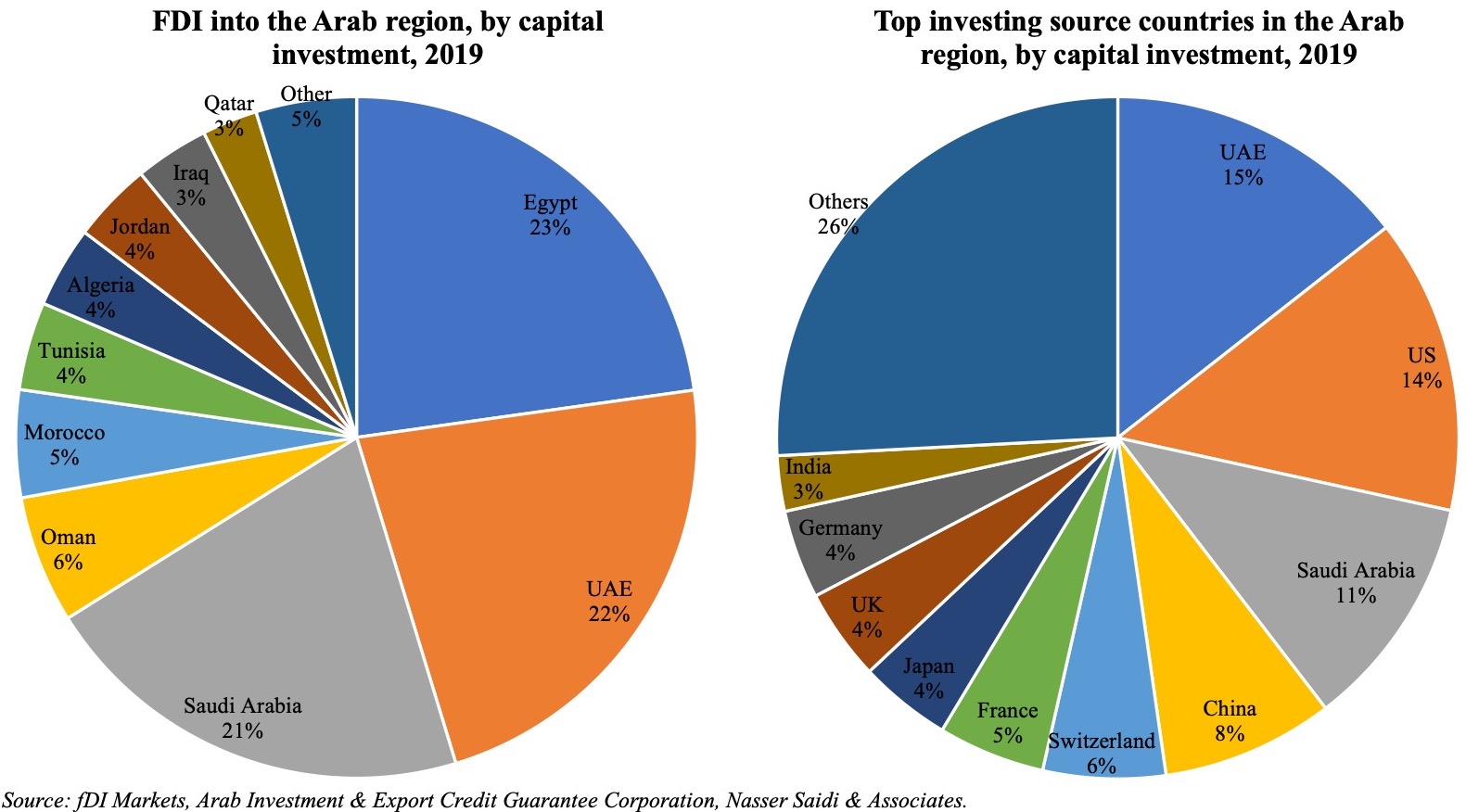

We focus on FDI in this Weekly Insight piece. FDI inflows are essential to the UAE’s diversification efforts, as it would not only create jobs, raise productivity and growth, but could also lead to transfer of technology/ technical know-how and promote competition in the market. According to the IMF, closing FDI gaps in the GCC could raise real non-oil GDP per capita growth by as much as 1 percentage point.

We focus on FDI in this Weekly Insight piece. FDI inflows are essential to the UAE’s diversification efforts, as it would not only create jobs, raise productivity and growth, but could also lead to transfer of technology/ technical know-how and promote competition in the market. According to the IMF, closing FDI gaps in the GCC could raise real non-oil GDP per capita growth by as much as 1 percentage point.

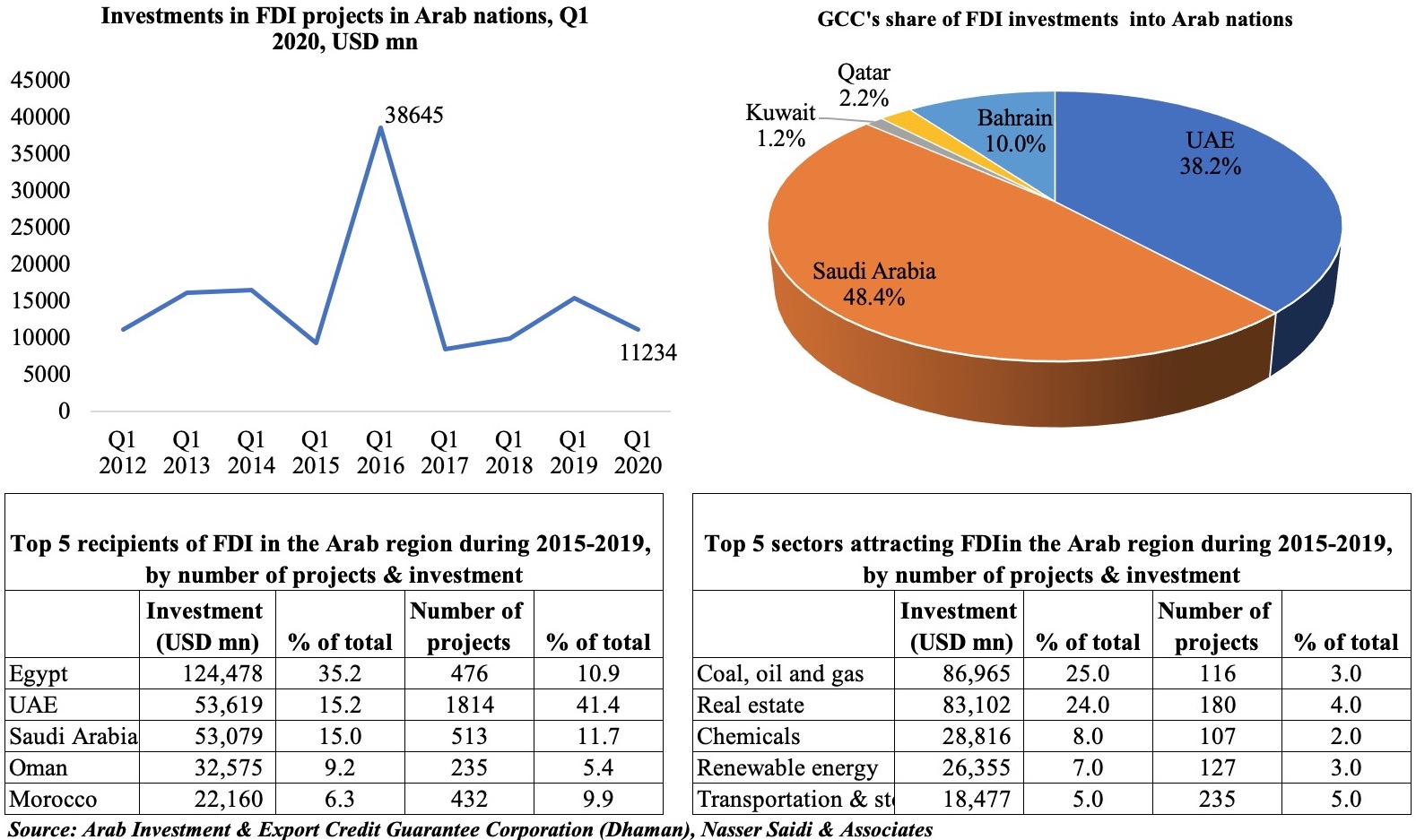

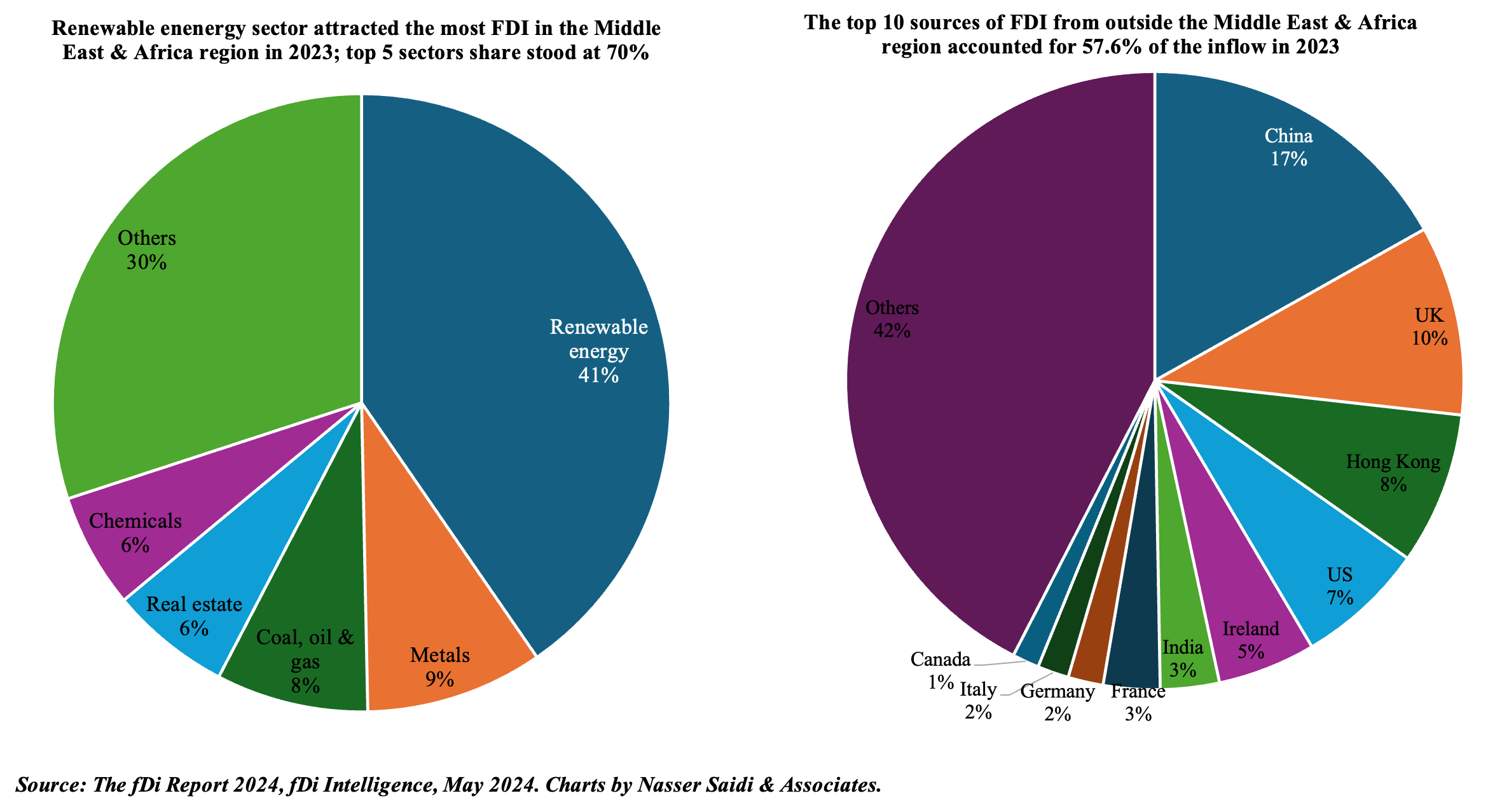

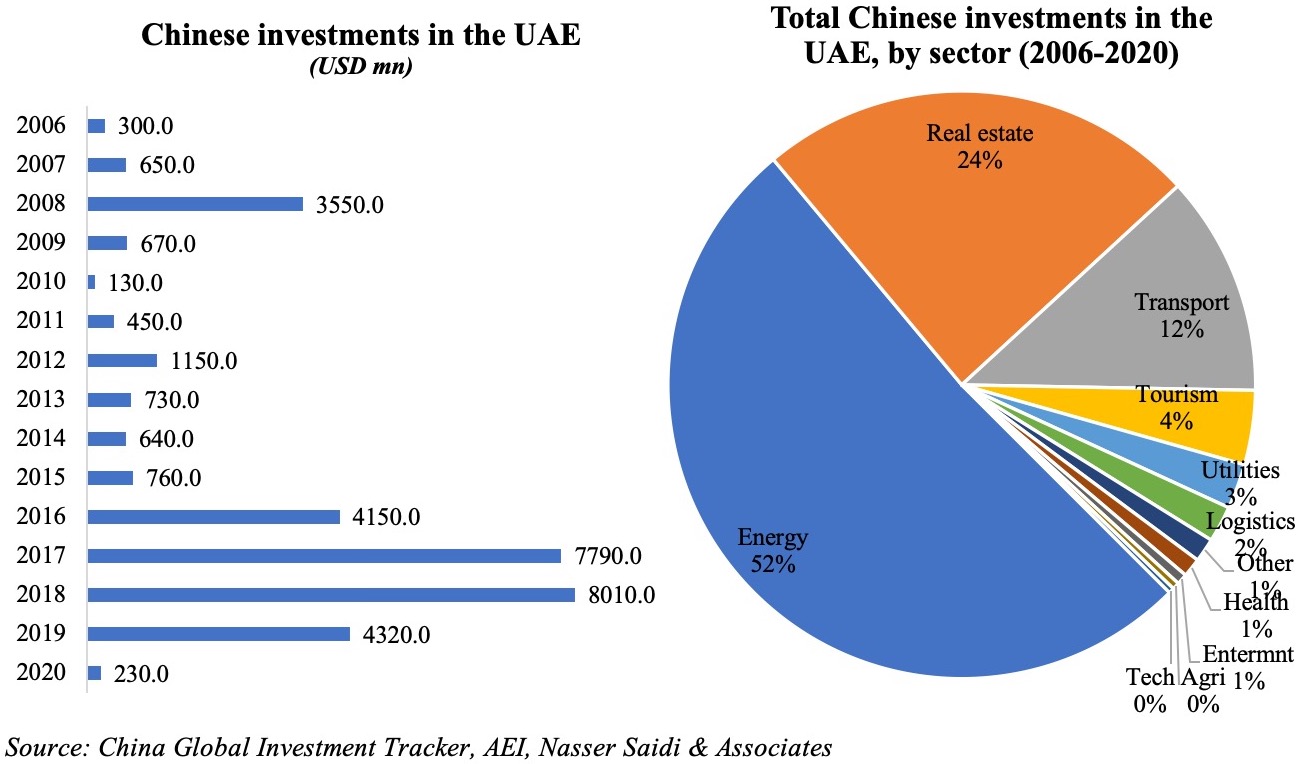

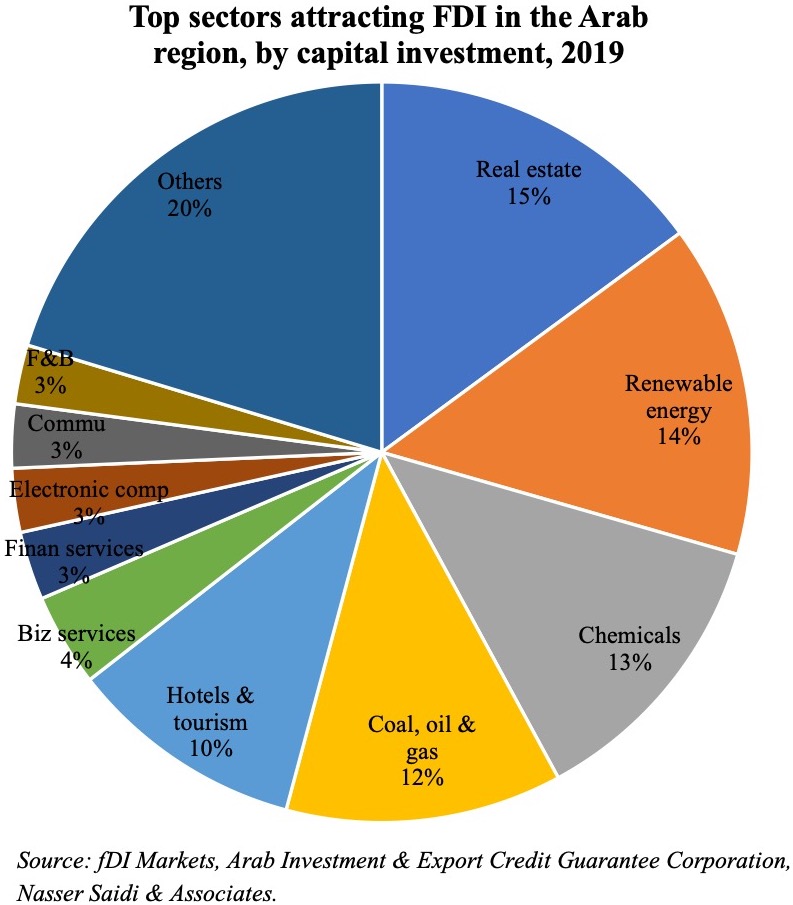

hinese projects tracked during Jan 2003-Mar 2020 (with the number of projects in double-digits in 2018 and 2019). According to AEI’s China Global Investment Tracker, the value of Chinese investments touched a high of USD 8bn in 2018, thanks to a handful of large projects (including with ACWA Power and Abu Dhabi Oil). Sector-wise, investments were concentrated in energy (both oil and gas as well as renewables), real estate and transport – together accounting for 87.8% of total investments during 2016-2020. This is largely in line with FDI inflows into the Arab region as well, with the top 5 sectors (real estate, renewables, chemicals, oil & gas and travel & tourism) accounting for close to two-thirds of total inflows in 2019.

hinese projects tracked during Jan 2003-Mar 2020 (with the number of projects in double-digits in 2018 and 2019). According to AEI’s China Global Investment Tracker, the value of Chinese investments touched a high of USD 8bn in 2018, thanks to a handful of large projects (including with ACWA Power and Abu Dhabi Oil). Sector-wise, investments were concentrated in energy (both oil and gas as well as renewables), real estate and transport – together accounting for 87.8% of total investments during 2016-2020. This is largely in line with FDI inflows into the Arab region as well, with the top 5 sectors (real estate, renewables, chemicals, oil & gas and travel & tourism) accounting for close to two-thirds of total inflows in 2019.