“Home is where the heart is for GCC wealth funds”, Op-ed in Arabian Gulf Business Insight (AGBI), 5 Sep 2024

The below opinion piece titled “Home is where the heart is for GCC wealth funds” was published in the Arabian Gulf Business Insight (AGBI) on 5th September 2024.

An extended version of the published article is posted below.

Home is where the heart is for GCC wealth funds

The Gulf’s SWFs are stepping up domestic investment

Globally, state-owned investors (SWFs, public pension funds and central banks) are a massive player in financial markets, managing USD 49.7trn in 2023, with SWFs posting a record high USD 11.2trn. GCC SWFs assets touched a peak of USD 4.1trn in 2023. Five GCC SWFs are among the top 10 most active dealmakers globally (Saudi PIF, Abu Dhabi’s ADIA, Mubadala and ADQ, and Qatar’s QIA), supported by the recovery of markets and higher oil prices post-Covid. They were active as well, representing 40% of all investments deployed by sovereign investors last year. But the asset allocation of portfolios is shifting. While GCC SWFs invested in overseas markets (e.g. PIF and ADQ preferred investments in emerging markets; ADIA had three-quarters of its investment value in North America and Europe), they are increasingly shifting to support domestic economic diversification, becoming more active in local and regional opportunities.

Why are GCC SWF strategies changing?

They are three major drivers.

Firstly, Cold War II is unfolding with growing economic, trade and investment fragmentation and dislocation, threatening deglobalisation and the tectonic shift in global economic geography towards Emerging Asia over the past two decades. Global geo-economic-political risks are growing with historically high debt levels of USD 313trn in 2023, regional wars (Europe, Near East) along with volatile interest rates. Sovereigns also face the risk of the growing weaponisation of the US dollar along with potential sanctions, a freezing and confiscation of assets, (witness Russia) that undermine the rule of law, the operation and architecture of global financial markets. The GCC have to derisk Western financial markets and assets to protect their wealth. Given SWIFT payment system risks, expect the BRICS+ and GCC to develop an alternative multilateral payment system, use national currencies for bilateral payments and the PetroYuan for energy. The era of free flowing GCC petrodollars is ending.

Secondly, national security considerations increasingly dominate economic policy making globally and regionally. It is imperative for the GCC to shift focus to domestic economic objectives and address domestic and regional opportunities and challenges (economic diversification, food security, AI and related tech, clean energy transition, climate risk mitigation and adaptation). Witness PIF’s investments in Saudi airlines and giga projects, ADQ’s investing $35 bn in Egypt’s Ras El-Hekma this year.

PIF’s Annual Report 2023 highlights the realities of the changing investment objectives. While AUMs have grown massively (from SAR 563bn in 2015 to SAR 2.9trn in 2023,), the share of international investments share is down (from 29% in 2021 to 20% in 2023), a smaller share of a growing pie. The PIF’s domestic economic objectives are increasingly aligned with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 and the broad goal of economic diversification, transformation and modernisation, necessitating an inward-focused agenda. Accordingly, the PIF aims to increase AUM to approximately SAR 4trn by 2025, raising the non-oil GDP and job creation contribution of PIF & subsidiaries to a cumulative SAR 1.2trn and to SAR 7.5trn by 2030.

To support Saudi’s maturing economy, PIF has launched 95 companies since 2017, spanning 13 strategic sectors ranging from EVs to sports and tourism, injecting about SAR 150bn into the local economy annually. Complementing Saudi Arabia’s pro-private sector policies, the PIF has been supporting SMEs and innovative, growth companies in new and emerging sectors. PIF has also been instrumental in attracting firms in innovative sectors to locate in the Kingdom – for example Lucid’s advanced manufacturing plant in Saudi to produce EVs, a SAR 1bn tech fund to attract chip-design companies and Alat’s deals in semiconductors & next generation infrastructure among other.

Thirdly, Saudi remains a developing economy and a vast country with massive investment opportunities for foreign investment and technologies. PIF’s engagement in supporting capital market development (e.g. listing of Saudi ETFs in Shanghai and Shenzhen, launch of a Riyadh-based multi-asset investment management platform with BlackRock), developing Saudi’s vast unexplored and unexploited mineral wealth (through PIF-backed Manara Minerals), supporting Saudi Industrial Policy (e.g. localising renewable energy components in collaboration with Envision Energy, support from Alat to manufacture robotic systems & heavy machinery) aim to attract FDI and PPP. The PIF is also supporting Saudi’s regional economic expansion and integration strategy, including involvement in developing the Red Sea Council and Western Saudi areas as a stepping stone into the African Continental Free Trade Area, along with the establishment of five companies for investment in Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Oman and Sudan.

Ahead of 2030 and as it builds capacity, reallocates its assets and investments, the PIF will increasingly become like Temasek, Singapore’s Public Wealth Fund, taking responsibility to improve the management, performance and productivity of Saudi’s vast public assets (e.g. public infrastructure and commercial assets). Saudi adoption and implementation of a robust Public Investment Management frameworks and moves towards a centralised model of the ownership and governance of public commercial assets held by various ministries/agencies– would not only increase financial returns and maximise the value of the public assets, but it would also increase productivity growth and support fiscal sustainability. Accountability is the other building bloc. PIF has taken a lead in promoting transparency: it is currently placed joint second globally and first in the Middle East for Governance, Sustainability & Transparency in a ranking of the top 100 SWFs by Global SWF.

The bottom line is that GCC SWFs (along with the BRICS+) are gradually redrawing the global financial architecture and landscape and supportive payment system, to becoming more regional and serving domestic economic objectives. This has also supported the creation and growth of an asset management industry in the financial centres of the region (working for the region) versus the prior experience of recycling petrodollars through global financial centres abroad.

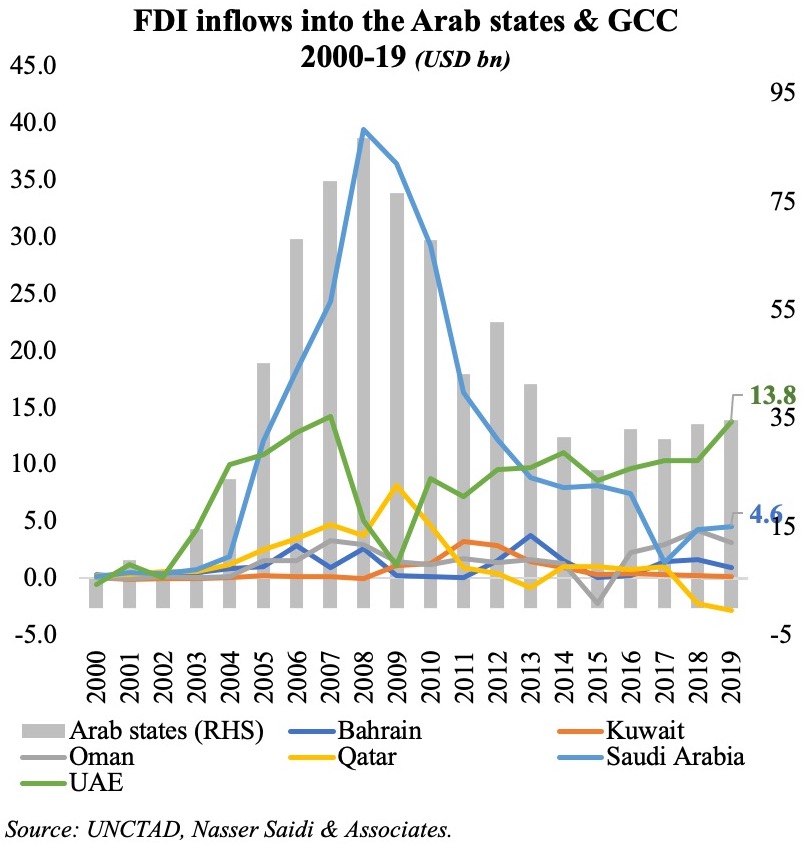

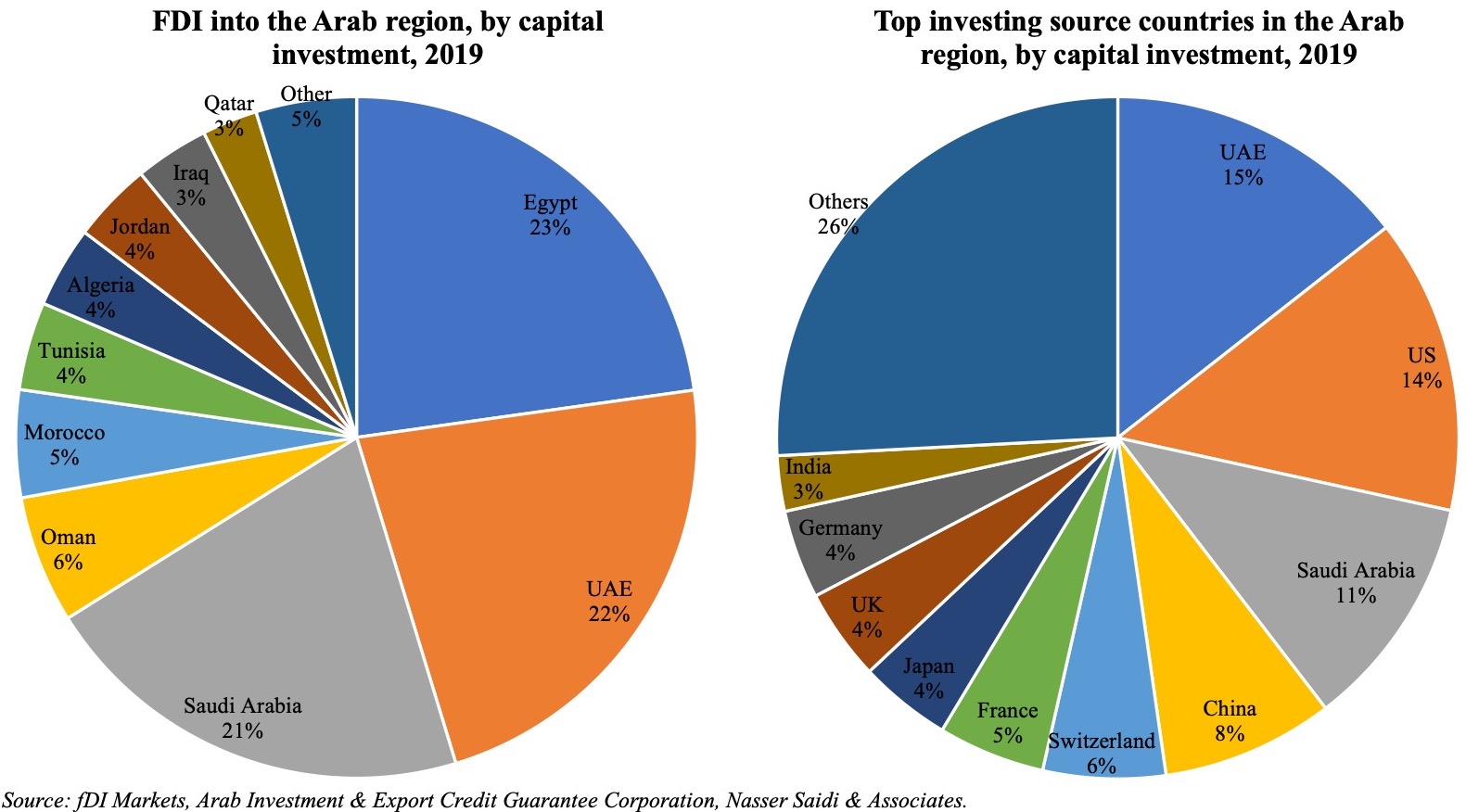

We focus on FDI in this Weekly Insight piece. FDI inflows are essential to the UAE’s diversification efforts, as it would not only create jobs, raise productivity and growth, but could also lead to transfer of technology/ technical know-how and promote competition in the market. According to the IMF, closing FDI gaps in the GCC could raise real non-oil GDP per capita growth by as much as 1 percentage point.

We focus on FDI in this Weekly Insight piece. FDI inflows are essential to the UAE’s diversification efforts, as it would not only create jobs, raise productivity and growth, but could also lead to transfer of technology/ technical know-how and promote competition in the market. According to the IMF, closing FDI gaps in the GCC could raise real non-oil GDP per capita growth by as much as 1 percentage point.

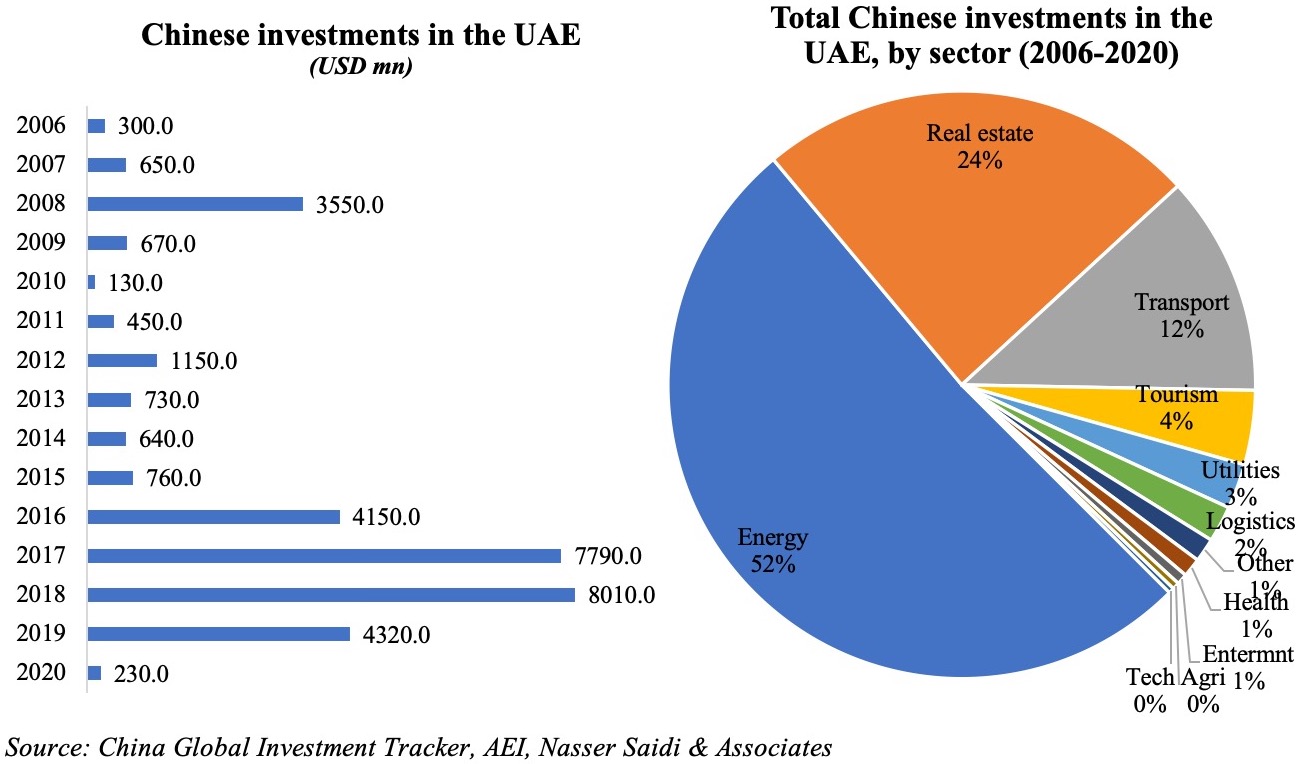

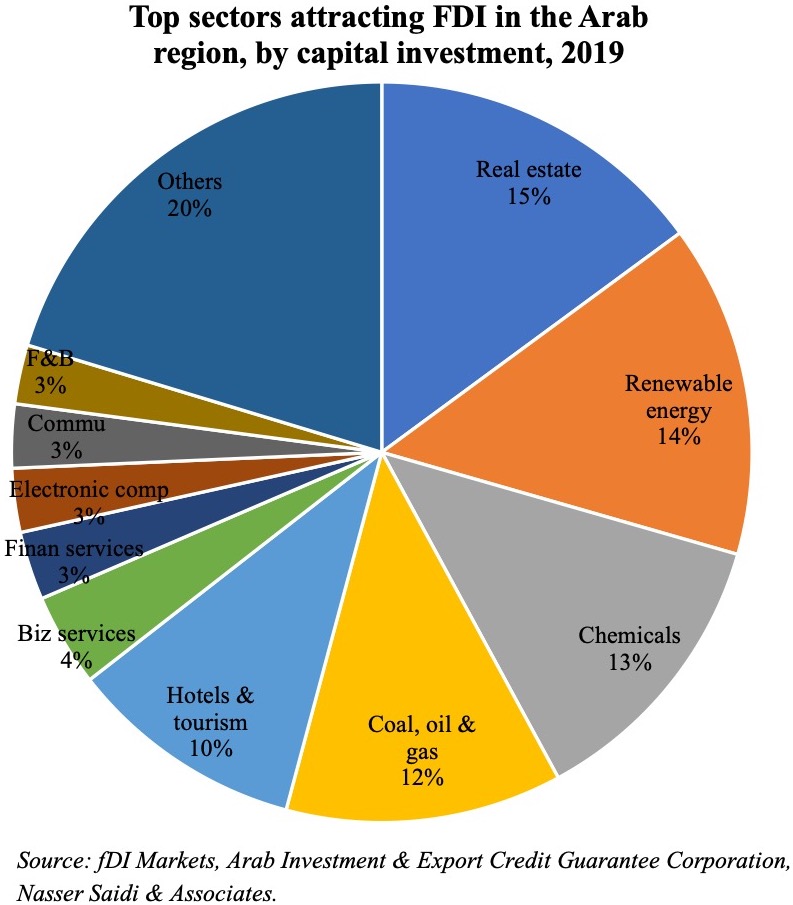

hinese projects tracked during Jan 2003-Mar 2020 (with the number of projects in double-digits in 2018 and 2019). According to AEI’s China Global Investment Tracker, the value of Chinese investments touched a high of USD 8bn in 2018, thanks to a handful of large projects (including with ACWA Power and Abu Dhabi Oil). Sector-wise, investments were concentrated in energy (both oil and gas as well as renewables), real estate and transport – together accounting for 87.8% of total investments during 2016-2020. This is largely in line with FDI inflows into the Arab region as well, with the top 5 sectors (real estate, renewables, chemicals, oil & gas and travel & tourism) accounting for close to two-thirds of total inflows in 2019.

hinese projects tracked during Jan 2003-Mar 2020 (with the number of projects in double-digits in 2018 and 2019). According to AEI’s China Global Investment Tracker, the value of Chinese investments touched a high of USD 8bn in 2018, thanks to a handful of large projects (including with ACWA Power and Abu Dhabi Oil). Sector-wise, investments were concentrated in energy (both oil and gas as well as renewables), real estate and transport – together accounting for 87.8% of total investments during 2016-2020. This is largely in line with FDI inflows into the Arab region as well, with the top 5 sectors (real estate, renewables, chemicals, oil & gas and travel & tourism) accounting for close to two-thirds of total inflows in 2019.