The article, “Breaking the Cycle: How the Great Financial Crisis Can Prepare Us for the Next One“, written by Dr. Nasser Saidi for the inaugural issue of the Dubai Policy Review (published in Jan 2019) can be downloaded in both English and Arabic.

Breaking the Cycle: How the Great Financial Crisis Can Prepare Us for the Next One

“It takes all the running you can do to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that”

– the Red Queen in Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll

What can policymakers learn from the painful times of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) that hit the region hard a decade ago?

This article examines the economic landscape in the UAE prior to the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), the factors leading up to the crises, and the ongoing economic & financial policies that must be addressed to minimize economic downturn in the future. It extracts lessons and recommends responses to remedy identified policy gaps and fortify economic development while striding towards the future. Economic diversification, digitalisation, strengthening monetary and fiscal policy toolboxes, improving STEM education and looking East in foreign trade and investment strategies, are a few critical responses identified. These policy responses provide valuable lessons for policymakers across the region, while preparing for uncertain economic times in a region going through socio-economic and geopolitical turbulence.

A Decade Ago..

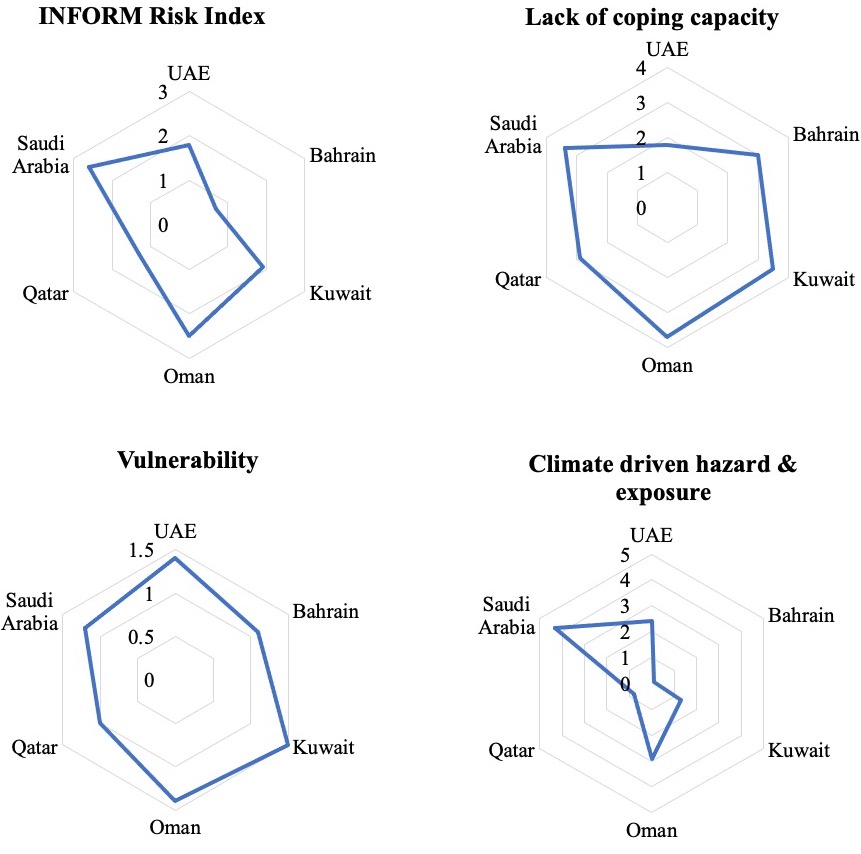

.. the Great Recession and the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) reverberated globally, with its destructive waves enveloping both advanced and emerging economies. Ten years later, the global economy is yet to fully recover, with the financial sector facing a debt bubble generated by ultra-loose monetary policy, historically low interest rates and quantitative easing (QE). The aftermath has seen sovereign states, corporations, and households build up debt in excess of $250 trillion worldwide. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries were not immune to the Great Recession and the GFC, left vulnerable and exposed through their large foreign direct and financial investments, and the oil market. Despite being the most diversified economy among its GCC counterparts, the United Arab Emirates still experienced a major hit from the sudden downturn. Ten years on, it remains oil-dependent and vulnerable to financial and oil market shocks. Oil exports and revenues in 2017 accounted for an estimated 34 percent of total exports (excluding re-exports) and 43 percent of government revenues, while the sovereign wealth funds (ADIA, DIC, Mubadala and others) are directly exposed to international financial market risks. Given the size of the oil sector and the dependence of government funding and spending on oil revenues, the economy of the UAE, is sensitive to commodity price shocks: boom-bust cycles driven by oil price volatility, as evidenced by the high correlation between oil prices and real economic activity.

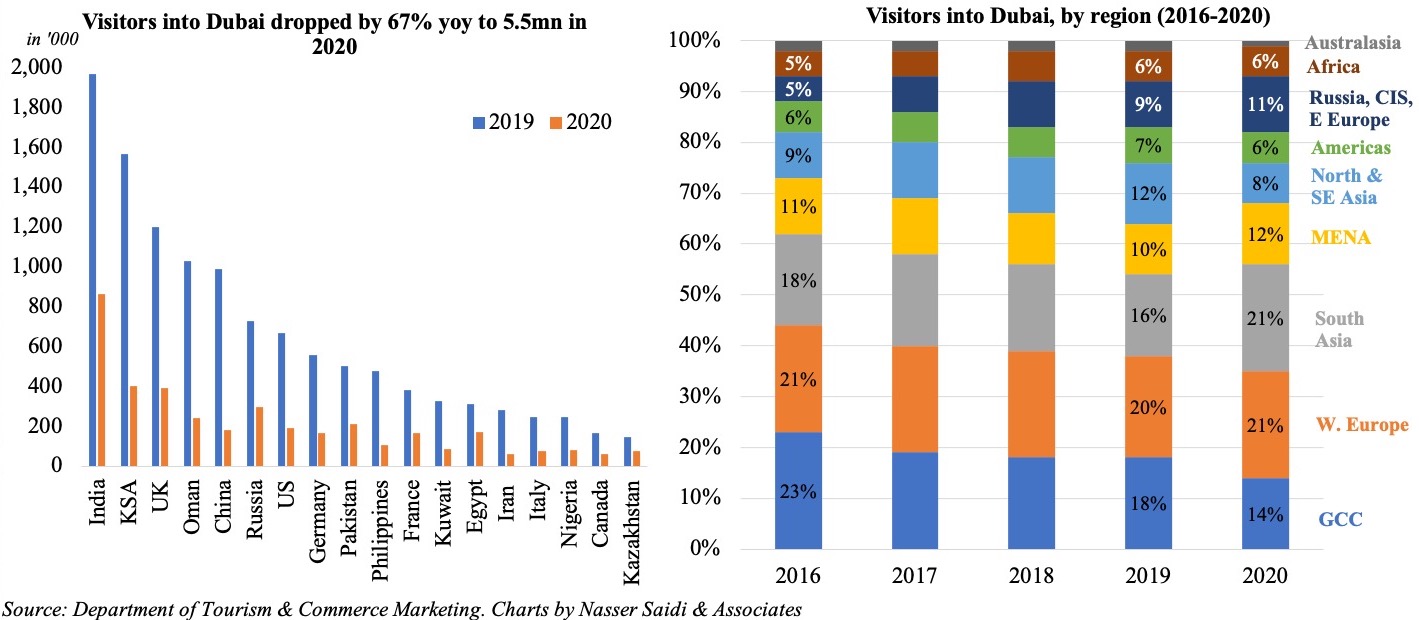

In addition, the Dubai development model, which is partly dependant on a “build-it-and-they-will-come” attitude to economic development, is subject to real estate and housing induced business cycles. Evidence of this can be found in the aftermath of the GFC and in the current downturn since 2016. Given the UAE’s exposure to international as well as region-specific and domestic shocks, are there lessons that can be learned from past crises? What policy adjustments are required to mitigate the risks of another crisis?

Exuberance, the 2008-2010 crisis and aftermath

Prior to the Great Recession and the GFC crisis, the Dubai/UAE economic development model was based on supportive demographics driven by a liberal policy of international labour mobility and high domestic population growth. The UAE economy also depended on investment in infrastructure – such as ports, airports and logistics – that facilitated international economic integration and development of the services sector (retail, trade and tourism). Business friendly policies, as well as an industrial policy based on economic clustering embodied in a multitude of Free Zones allowing 100 percent foreign ownership, with low or no taxation, resulted in large foreign direct investment flows, competition and economies of scale and economies of scope (generating a wider variety of goods and services). High population growth fuelled the construction industry, the real estate, housing and retail sectors as well as health and education to serve a young, fast-growing consumer base. Dubai’s economic growth, with its low direct dependence on oil (about 1% of GDP), was supported by a high contribution from its services sector – trade, retail, hospitality, tourism and transportation. Liberal domestic economic policies, along with political and macroeconomic stability, benefited from a supportive global environment of the “Great Moderation”, of decreased macroeconomic volatility and reduced volatility of business cycles. Altogether, this resulted in a dynamic business environment and high growth rates. Investors, businesses and consumers were exuberant – but vulnerabilities were building. Buoyant economic activity, supported by the oil price boom of 2003-08, rising consumer and investor confidence, and abundant liquidity led to credit growth, inflation, and asset price inflation, including real estate. But, investor exuberance and ‘animal spirits’ faced legacy institutional and policy vulnerabilities: an absence of a fiscal and monetary framework and policies geared at economic stabilization; an absence of coordination and lack of guiding strategy on foreign investment by State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and Government Related Enterprises (GREs); a real estate market bubble financed by foreign borrowing (in US dollars); and absence of centralized oversight and control over foreign borrowing by SOEs & GREs and the absence of a public debt policy and management. The stage was set for a domestic economic and financial crisis. At the onset of the GFC in 2008, banks in the Middle East, and more so in the GCC, were not highly leveraged and did not have any direct linkage or exposures to the US sub-prime crisis which triggered the GFC. Financial instruments like mortgage-backed securities (MBS), collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) and other instruments that became toxic assets, were absent from the local markets. Though the UAE banks were adequately capitalized and profitable, the fast pace of growth of personal, consumer and real estate loans, along with the uncertain outlook for asset prices in the UAE were worrisome signs alongside growing concerns about counterparty risk. Real, inflation adjusted, average credit growth was a blistering 26 percent a year during 2003–08 fuelling growth and the accompanying real estate bubble. Credit to the private sector rose by 51 percent year-on-year by Sep 2008, up from 40 percent in December 2007, driven by the economic boom and highly negative real interest rates – with credit, financed by strong deposit growth and large foreign borrowing in 2007. On the corporate sector side, the boom was associated with a sharp rise in leverage, including inter-company and supplier debt, increasing the sector’s vulnerability to funding availability, rollover risk and cost. Eventually, the bubble burst. Project cancelations, postponements and amendments amplified in the fourth quarter of 2008 and first quarter of 2009. About $39 billion of GCC debt (half from the UAE) was maturing, to be repaid or refinanced in 2009, at a time when liquidity had evaporated from the international and regional markets.

Twin Oil and Financial Shocks

The collapse of oil prices accompanying the GFC and the Great Recession was a twin shock, both economic and financial. The oil price shock directly impacted government and export revenues and the current account, with a spill over and an direct impact on financial market, banking and corporate liquidity. Funding costs jumped as speculative capital inflows reversed and investor confidence collapsed. Asset prices plunged, and when the Nakheel/Dubai World issues surfaced in Q4 2008, Dubai’s CDS rates (credit default swaps) skyrocketed, trading at nearly 2000, while Saudi Arabia’s rates were at 125. Pressures on bank funding and liquidity led to tight credit conditions. Dubai was engulfed in the GFC tsunami. What followed, with a lag, was the rollout of short-term policy measures including deposit guarantees, monetary easing and injection of liquidity which helped stabilize interest rates and liquidity conditions, alongside medium-term measures like real estate regulations geared to countering leverage and speculation. Ultimately, the crisis highlighted vulnerabilities related to the unsupervised leverage and foreign borrowing of SOEs and GREs, classical asset-liability mismatching, banks’ exposure to asset markets and their growing dependence on foreign correspondent bank financing, and a general weakness in their liquidity and risk management frameworks. It also exposed instances of weak regulatory and supervisory frameworks and enforcement at both banks and non-bank financial institutions. The crisis also brought to the forefront the need for greater government revenue diversification, given the macroeconomic and systemic risks of high dependence on volatile oil revenues. Last, but not least, the crisis uncovered the near absence of sound corporate governance practices and transparency, especially in the case of SOEs and GREs.

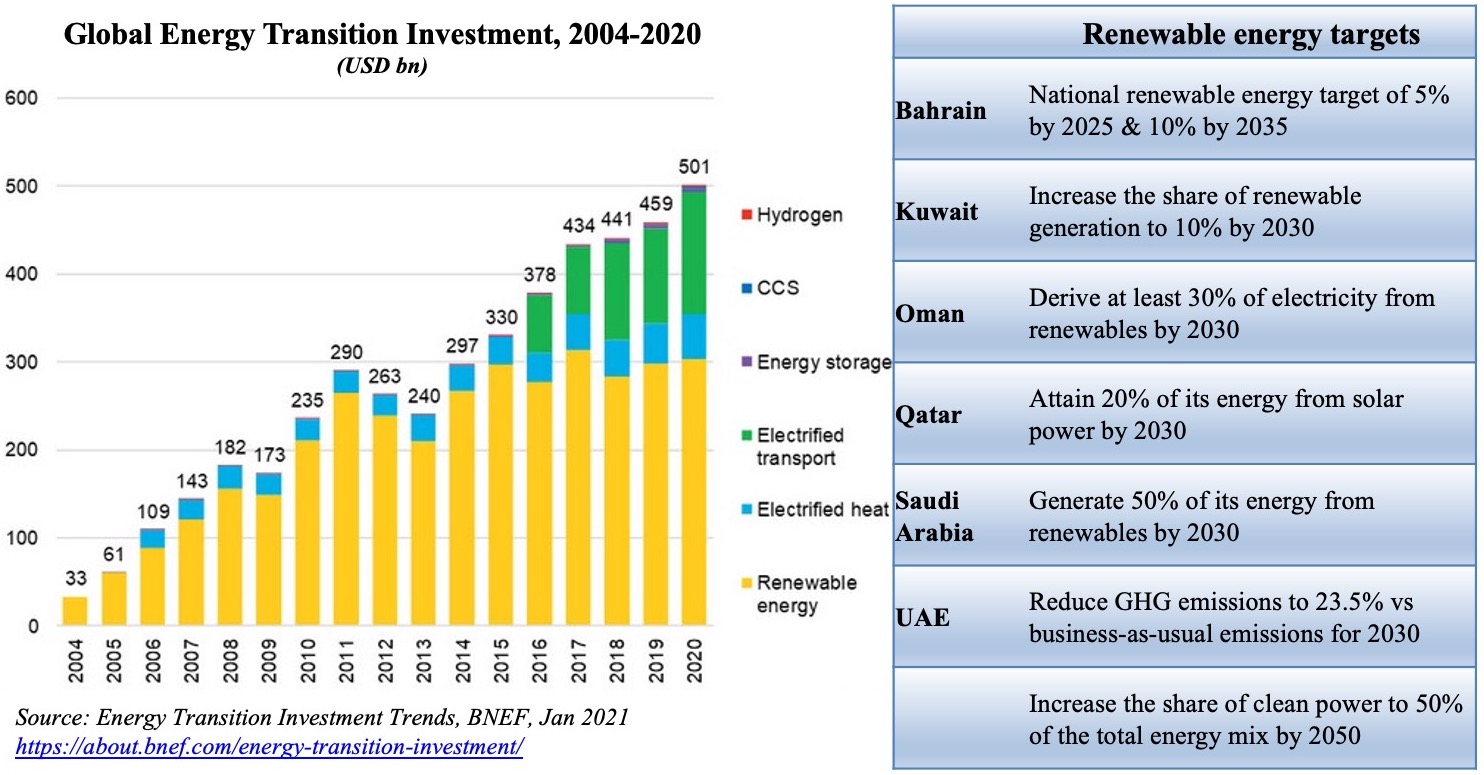

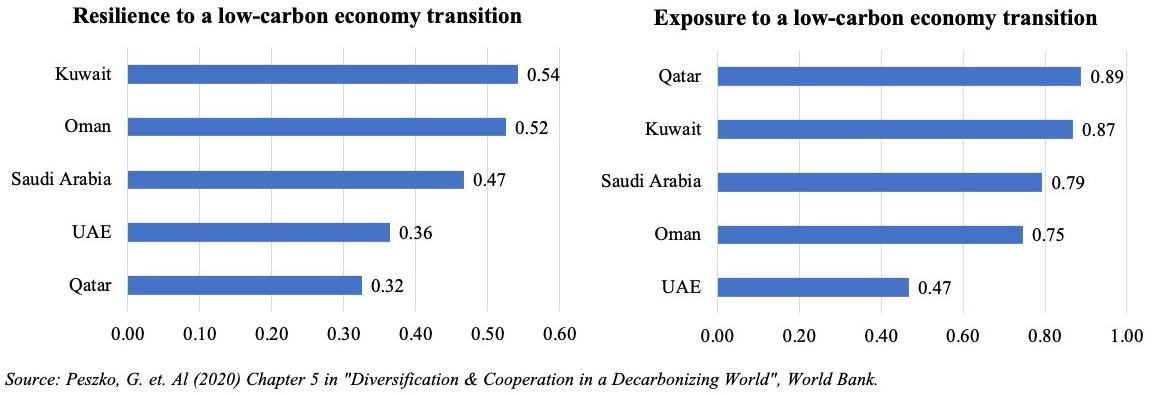

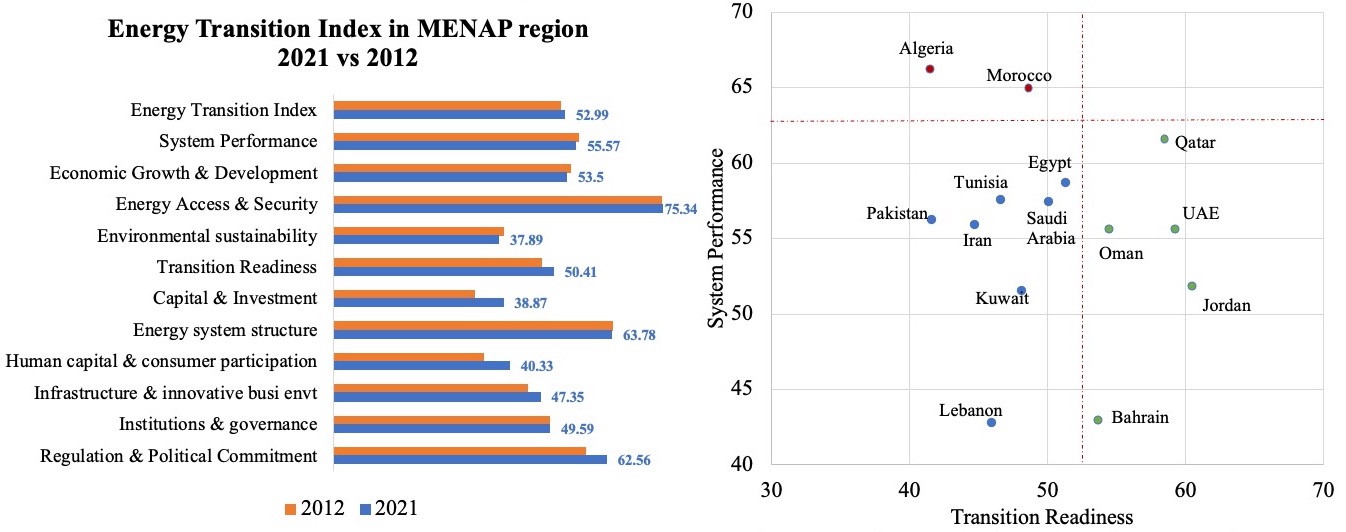

The ‘New Oil Normal’ Crisis

Oil prices have dipped from the three-digit heights of 2014 to as low as $30-40 per barrel in the past few years before a partial recovery in 2018. This “New Oil Normal” reflects new realities: technology and high oil prices have driven improving growing global energy efficiency (energy/GDP ratios are falling), COP 21 policy commitments are changing the energy mix away from fossil fuels, while disruptive technological innovations are making shale oil and gas, along with renewable energy sources like solar and wind, directly competitive with fossil fuels. In short, both demand side and supply side factors imply downside risks for oil prices, despite short-term supply disruptions due to geopolitical developments or attempts by OPEC to limit production, including through unsustainable non-OPEC alliances. Over the medium and long-term, the UAE and other oil exporters run the risk of owning stranded fossil fuel assets, which are not economical to exploit. Developing and investing into higher value-added uses of oil & gas, downstream activities, and privatization through the public listing of energy assets should be part of a national fossil fuel de-risking strategy.

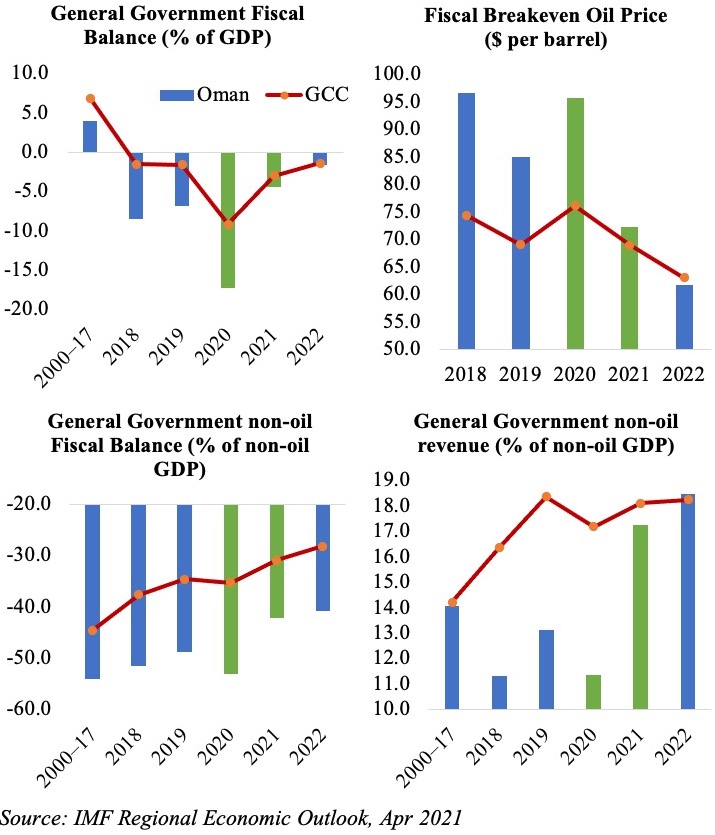

Pro-cyclical fiscal policy exacerbates oil price boom-bust cycles

Oil boom-bust crises, including those in the UAE, were exacerbated by the pro-cyclical fiscal policies followed by oil exporters: driven by a balanced budget policy stance, governments tend to increase spending when oil prices are high and scale back spending when prices dip. This has direct and spill over effects on the non-oil sector (in particular infrastructure, construction, real estate) which experiences a slowdown in economic activity. The current mix of monetary tightening due to the ‘normalization’ of US monetary policy and the onset of Quantitative Tightening (QT) and fiscal austerity directly conflicts with the need to conduct a counter-cyclical stabilization policy. In order to adjust to the New Oil Normal, the policy mix should be changed to one that is monetary easing with lower interest rates along with fiscal stimulus, combined with structural reforms. However, monetary policy is constrained by the tight peg to the US dollar and the classical policy trilemma: you cannot simultaneously have monetary policy independence, fixed exchange rates and freedom of capital flows. The downside risk for oil prices weighs on the growth prospects for oil exporters, making greater economic diversification a policy imperative and requiring structural policy reforms and enabling and supportive fiscal policy.

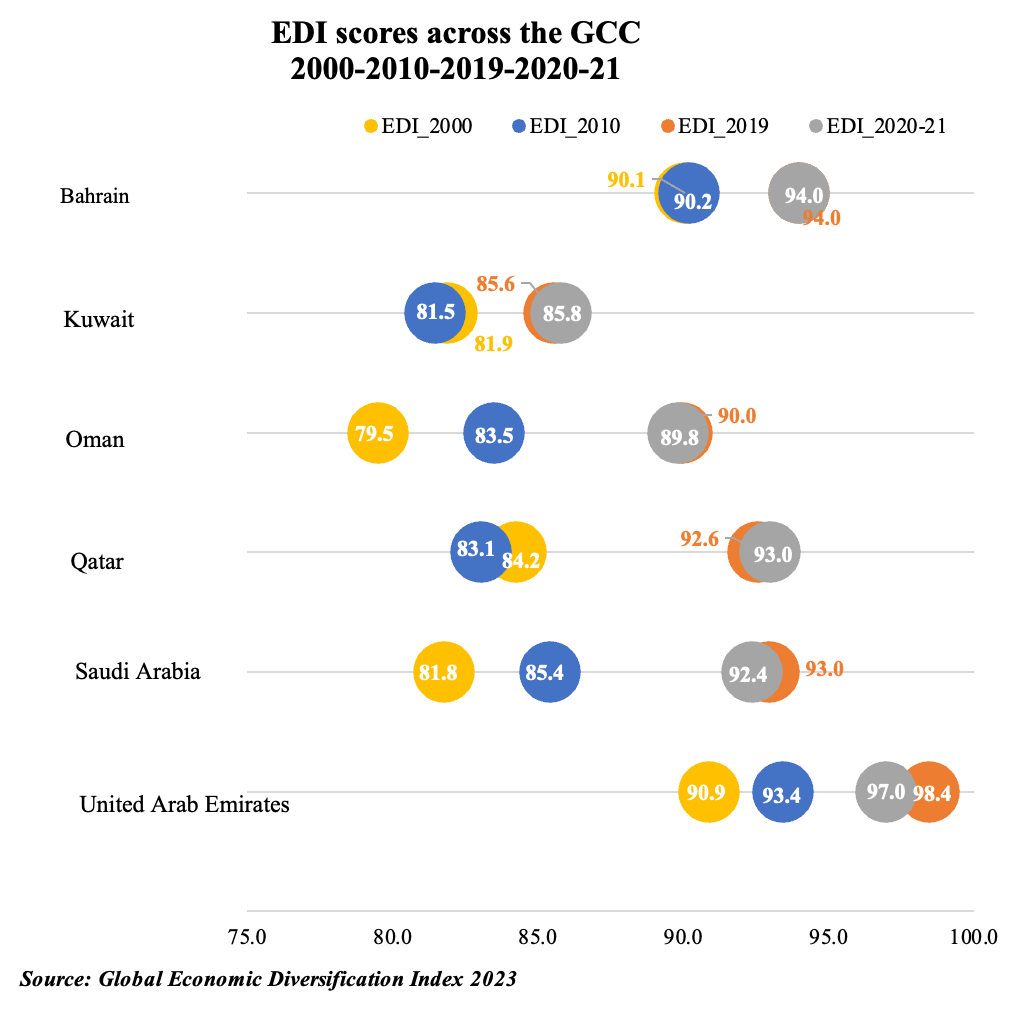

Economic Diversification is a Policy Imperative

Economic diversification leads to more balanced economies and is crucial for more sustainable economic growth and development. For the UAE (and other fossil fuel exporters), diversification is critical to reducing exposure to the volatility and uncertainty of the global oil market and related boom-bust cycles. Greater diversification is needed across three dimensions: structure of production (supporting the non-oil private sector), trade (developing non-oil exports) and at the fiscal level (diversifying sources of revenue). A successful diversification strategy would: re-orient the economy towards more knowledge based and innovation-led activities (including higher value-added in the energy sector), raising productivity growth and creating new jobs; directly support greater private sector activity, including in the tradable sector; provide more sustainable public finances that are less dependent on revenues from natural resources; generate greater macroeconomic stability and gradually de-risk fossil fuel assets through gradual privatization and divestment in the financial markets.

Economic policy and Reform: Minimizing Vulnerability to Next Crisis

Build local currency financial markets and develop a counter-cyclical fiscal policy toolbox for economic stabilization to allow for deficit financing, along with the institution of fiscal rules for long-term fiscal sustainability. A major lesson from the GFC and from the Asian crisis, is the danger of over reliance on foreign currency bank financing for cyclical sectors like housing, real estate and long gestation infrastructure investment. The UAE needs to focus on developing local currency financial markets starting with a government debt market to finance budget deficits, infrastructure and development projects, along with a housing finance/mortgage market. Market financing for infrastructure and development projects is more appropriate for longer-dated investments than bank financing.

Unification of local financial markets. There are three operational financial markets in the UAE – the Abu Dhabi Securities Exchange, the Dubai Financial Market, and Nasdaq Dubai in the DIFC. These fragmented markets should be consolidated to create a deeper, broader, and more liquid and active market, regulated and supervised by an Emirates Capital Markets Authority.

Establish a modern and credible legal and regulatory financial infrastructure. Enhance debt enforcement regimes by decriminalizing bounced cheques and building the capacity of the courts; develop insolvency frameworks to support out-of-court settlement, corporate restructuring and adequately protect creditors’ rights. Introduce laws to facilitate mergers and acquisitions, as well as securitization to support the development of asset backed and mortgage backed securities and other structured debt instruments.

Develop a counter-cyclical fiscal policy toolbox for economic stabilization. This requires reforming the budget law framework, inherited from colonial days, to allow for deficit financing, along with the institution of fiscal rules for long-term fiscal sustainability. Given the recent passage of the UAE Federal Debt Law, the government should accelerate the set-up of the public debt management office.

Favour greater exchange-rate flexibility and monetary independence. The peg to the US dollar has exacerbated the negative impact of pro-cyclical fiscal policy. While the policy peg gives the UAE dirham policy credibility, it has prevented real exchange rate depreciation and fails to reflect the deep structural changes in the UAE’s economic and financial links over the past three decades – particularly the shift away from the United States and Europe and toward China and Asia. The timing is opportune to move to a peg to a currency basket including the euro, Yen and Chinese Yuan, along with the US dollar.

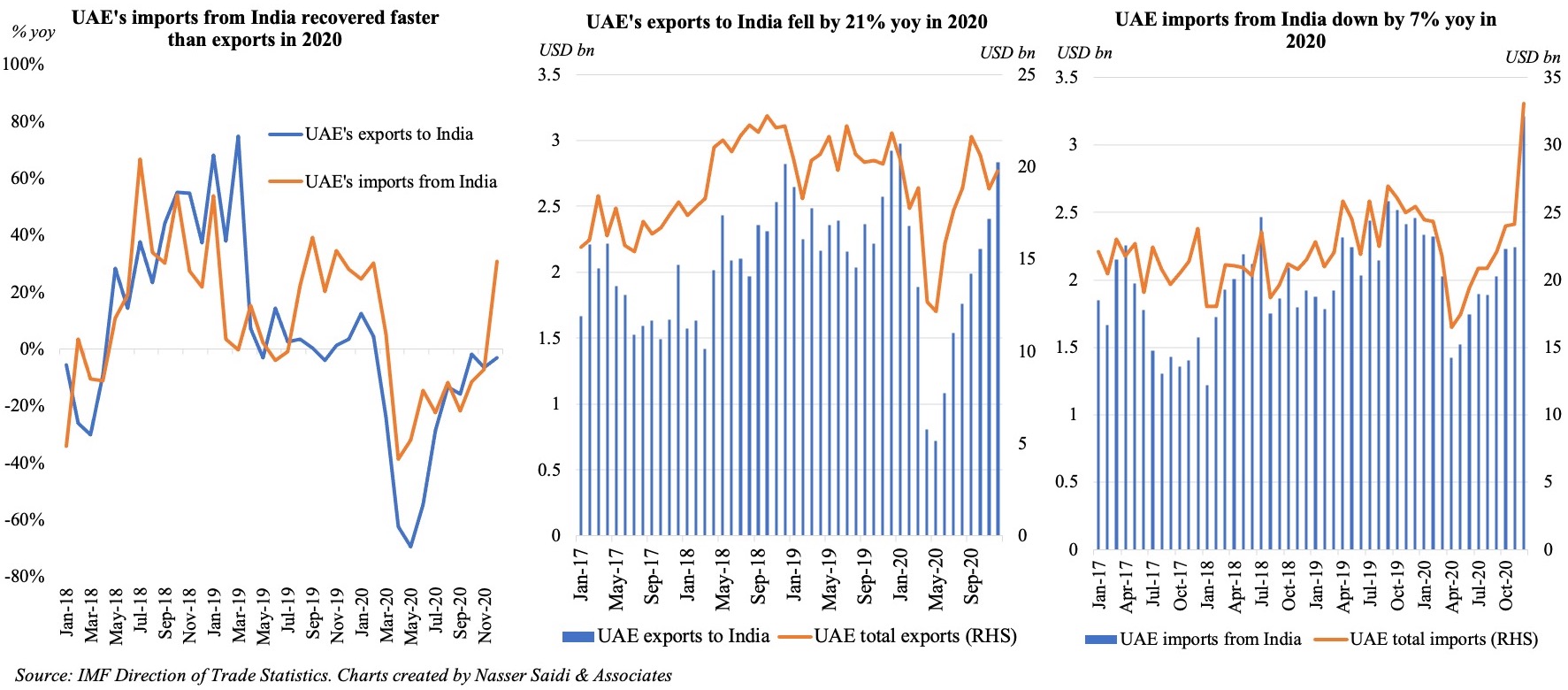

Trade policy reform to adapt to the new global economic geography. Given the global shift in trade and investment patterns towards emerging markets and Asia, the UAE (with or without the GCC) should aim to negotiate trade and investment agreements with Asian countries (China, India, ASEAN-Plus-Six) as well as the COMESA countries. India is the UAE’s largest trading partner, while China is the strategic economic partner going forward (notably in light of the recently announced $10 billion UAE-China investment fund and the win-win potential from participating in China’s Belt & Road initiative).

Labour market reforms. The UAE has taken the first steps towards creating a more efficient labour market with the establishment of visas for part-time work/internship/apprenticeship and long-term residence rights (for selected professionals). The next steps would be permitting greater labour mobility, as well as flexible hours and the ability to work from home facilitated by modern technology. Abolishing the Kafala system may not be realized anytime soon, but is a necessary and important structural reform to retain expatriate human capital. The other major reform is continuing to break down the barriers to the economic participation and empowerment of women.

Education market reforms and building knowledge human capital. The educational system continues to focus on preparing students for public sector jobs, with a persistent skill mismatch and low educational quality compared to market requirements. Though spending per capita is high and student-teacher ratios are comparable to OECD levels, the outcomes are not strong. The PISA scores, for example, reveal that UAE students are placed 47th in math, 46th in science, and 48th in reading. Radical modernisation of education curricula is essential for creating a 21st century able workforce. It is time to invest in ‘Digital Education-for-Digital Employment’, vocational, and on-the-job training. Increasingly the focus should be to promote STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) – especially given the official policy focus on innovation and a shift to the digital e-economy and -services in the UAE and the region.

Competition and liberalisation of rights of establishment: Effective implementation of the new Investment Law (2018) to remove barriers to FDI by allowing 100 percent foreign ownership and the protection of property rights would galvanise the benefits of competition. It would encourage expatriates to invest locally, reducing the outflow of capital and remittances. Dubai’s free-trade zones are a testament to the success that comes with liberalization and the removal of barriers to foreign ownership and management. Permitting companies in the free zones to also operate in the “domestic economy” would stimulate investment and create jobs. Some companies have completed this transition, given recent regulatory changes in the DIFC, DED, and more recently in Abu Dhabi. Phasing out of the commercial agency system needs to be the obvious next step.

Digital transformation: The UAE has been the first mover in the region in embracing new digital technologies, including Blockchain/DLT (Distributed Ledger Technologies) and Artificial Intelligence. However, the Blockchain/AI movement needs regulatory support with the passage of enabling laws to facilitate AI, Blockchain, Big Data, and related technologies. Integrate and link public and private sector e-services databases through Blockchain (similar to Estonia’s X-Road). Leap ahead by teaching coding in kindergarten, to securing digital identities for every citizen and resident, allowing an “e-citizen” programme, an “onshore” Fintech regulatory sandbox, and eventually a UAE Digital Currency to facilitate digital transacting. Supporting and financing start-ups with incubators and accelerators and co-investing with the private sector (seed, VC, Angel and PE investors) would help drive the UAE’s digital transformation. Digitalisation also requires broad, deep, unencumbered and cheap access to digital highways: the telecoms sector should be open to competition both in the backbone and in services. China provides a good example of what can be achieved.

New energy & industrial policy: the UAE should rapidly diversify its energy mix by ramping up investment in clean energy (wind and solar) and technology (including desalination) which can become the basis of a new export industry. This frees up oil for export and contributes to decarbonisation and reducing pollution levels. Diversification should be private sector based to create new jobs. This requires liberalisation and competition for SOEs and GREs and establishing the legal and regulatory framework needed for privatization and public-private partnerships (PPPs). Privatization and PPPs in infrastructure, new and old energy, health, education, transport, telecoms and logistics would could attract massive domestic and foreign investment. Similarly, SWF investment strategy should shift to further support economic diversification policies and co-invest with domestic and foreign investors in new technologies and innovative sectors including clean energy, robotics, AI, Blockchain/DLT, Machine Learning, Fintech, and related tech.

Principles of Stabilization in Turbulent Times

Arab countries and oil and natural resource based economies face multiple economic, geostrategic, and climate change challenges as they seek to adapt and integrate into a rapidly changing global economic landscape and geography. The high level of dependence of both oil exporters and oil importers on oil revenues and oil assets poses an existential risk. The “New Oil Normal” and global move to decarbonisation imply permanently lower real oil prices and the risk that oil assets become stranded assets, with marginal economic value, in the absence of new innovations and new, clean, uses for fossil fuels. The UAE’s experience and economic diversification achievements provide a broad policy framework for Gulf oil producers. However, there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’. Moving forward, five principles should guide strategists and policy makers: (i) Economic diversification is a strategic imperative encompassing production, trade and government revenue diversification; (ii) Facilitate and enable the rapid digitalisation of the economy and society by, among other, removing barriers in the telecoms sector; (iii) Pivot policy towards emerging economies, towards India, China, ASEAN and the COMESA countries through innovative trade and investment agreements. The UAE and the region needs to participate in the new global value chains emerging from the Belt & Road and its ramifications. (iv) Education curricula require radical reform towards STEM and enabling ‘Digital Education for Digital Employment’. (v) Develop a modern economic – monetary and fiscal – policy toolbox allowing policy makers to undertake economic stabilization and counter-cyclical measures.

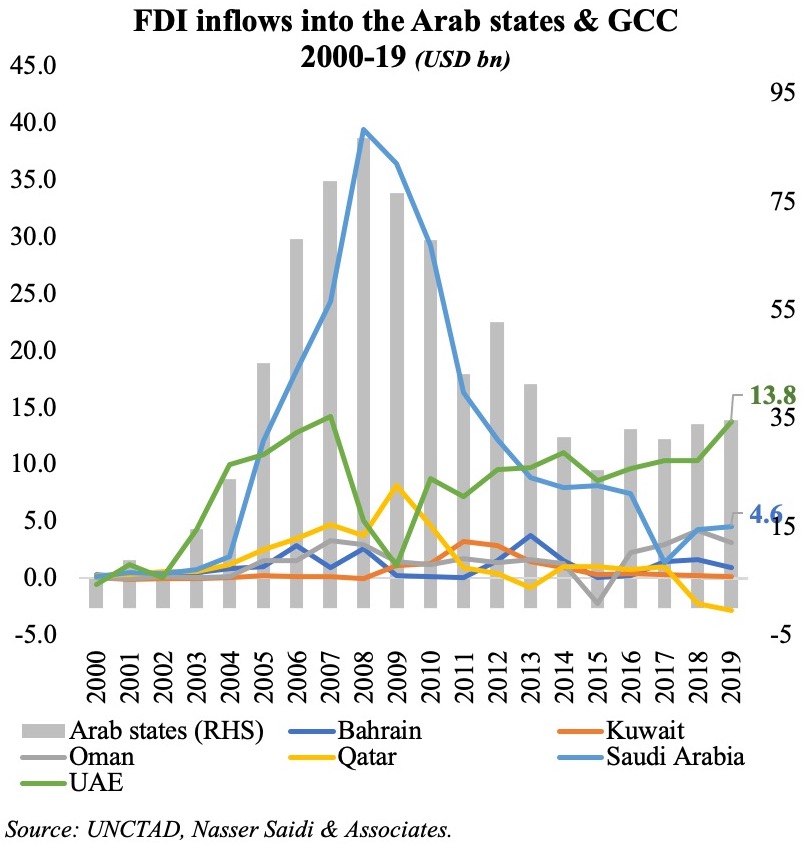

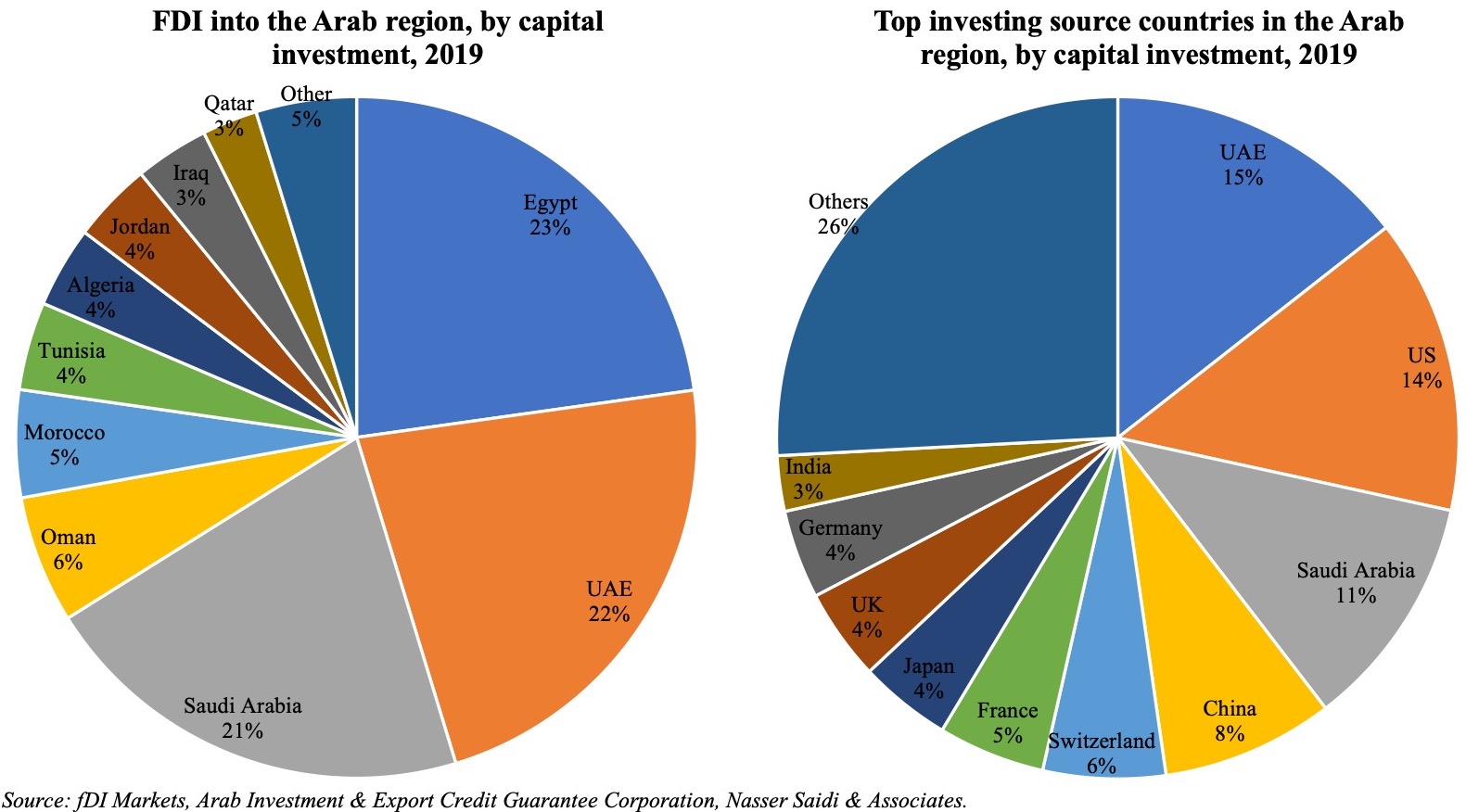

We focus on FDI in this Weekly Insight piece. FDI inflows are essential to the UAE’s diversification efforts, as it would not only create jobs, raise productivity and growth, but could also lead to transfer of technology/ technical know-how and promote competition in the market. According to the IMF, closing FDI gaps in the GCC could raise real non-oil GDP per capita growth by as much as 1 percentage point.

We focus on FDI in this Weekly Insight piece. FDI inflows are essential to the UAE’s diversification efforts, as it would not only create jobs, raise productivity and growth, but could also lead to transfer of technology/ technical know-how and promote competition in the market. According to the IMF, closing FDI gaps in the GCC could raise real non-oil GDP per capita growth by as much as 1 percentage point.

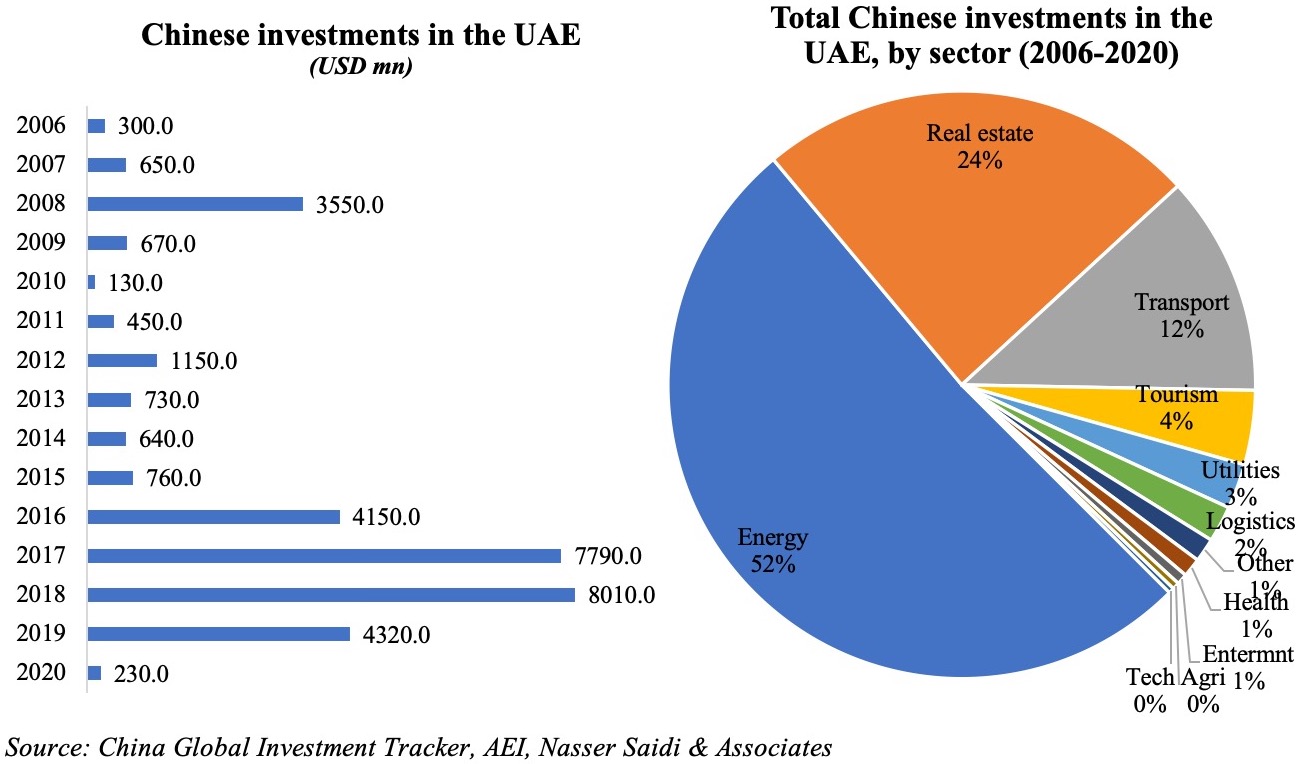

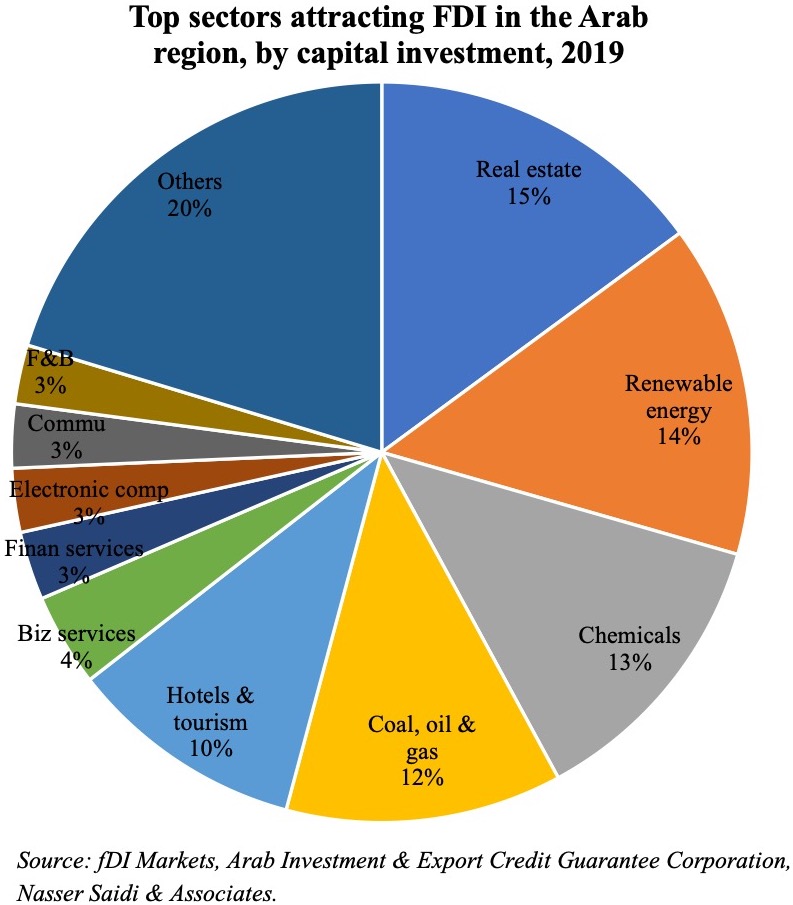

hinese projects tracked during Jan 2003-Mar 2020 (with the number of projects in double-digits in 2018 and 2019). According to AEI’s China Global Investment Tracker, the value of Chinese investments touched a high of USD 8bn in 2018, thanks to a handful of large projects (including with ACWA Power and Abu Dhabi Oil). Sector-wise, investments were concentrated in energy (both oil and gas as well as renewables), real estate and transport – together accounting for 87.8% of total investments during 2016-2020. This is largely in line with FDI inflows into the Arab region as well, with the top 5 sectors (real estate, renewables, chemicals, oil & gas and travel & tourism) accounting for close to two-thirds of total inflows in 2019.

hinese projects tracked during Jan 2003-Mar 2020 (with the number of projects in double-digits in 2018 and 2019). According to AEI’s China Global Investment Tracker, the value of Chinese investments touched a high of USD 8bn in 2018, thanks to a handful of large projects (including with ACWA Power and Abu Dhabi Oil). Sector-wise, investments were concentrated in energy (both oil and gas as well as renewables), real estate and transport – together accounting for 87.8% of total investments during 2016-2020. This is largely in line with FDI inflows into the Arab region as well, with the top 5 sectors (real estate, renewables, chemicals, oil & gas and travel & tourism) accounting for close to two-thirds of total inflows in 2019.