“Global Economic Diversification Index 2025”, report released at the World Governments Summit, Feb 2025

“Global Economic Diversification Index 2025” was released by the Mohammed Bin Rashid School of Government (MBRSG) at the World Governments Summit held in Dubai on 12th Feb 2025. Dr. Nasser Saidi & Aathira Prasad were co-authors of the report, which was developed in cooperation with Keertana Subramani, Salma Refass and Fadi Salem (MBRSG) and Ben Shepherd (Developing Trade Consultants).

Access the latest and past reports as well as the underlying data on the website.

Effective governance of economic diversification efforts is highly reliant on the availability of representative and robust data that informs evidence-based development and policy directions. The Global Economic Diversification Index (EDI) 2025 report provides valuable longitudinal datasets to inform policy, research and economic development efforts across the globe. It specifically highlights the importance of economic diversification for commodity-producing nations to mitigate the risks of growth, trade, and revenue volatility. The report underscores the vulnerability of countries dependent on commodities to various shocks, such as price fluctuations, climate change, and global pandemics. Successful diversification can be accelerated through adopting new technologies and digitalisation, moving towards a services-based economy, focusing on value-added manufacturing, and investing in human capital and infrastructure.

The findings of this latest edition of the EDI emphasises the need for commodity-dependent nations, particularly those reliant on oil and gas, to adopt policies that prevent the natural resource curse and promote sustainable economic growth. Globally, there are numerous examples of successful transitions, including Norway’s diversification into high-tech sectors and Malaysia’s move towards greater industrialisation. However, the report highlights that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to diversification, as the urgency and pace of reform depend on multiple factors, including institutional effectiveness and governance, among others.

The Economic Diversification Index, first published in 2022, provides a comprehensive measure of economic diversification across countries. The EDI, derived by calculating the scores of three key sub-indices: government revenue, output, and trade, allows countries to assess the state and evolution of their economic diversification, as well as compare themselves with peers, and identify factors that can foster or impede diversification. The 2025 edition covers the performance of 115 countries, using publicly available quantitative indicators to ensure transparency and allowing reproducibility of the results.

The top-ranked EDI nations in the current EDI edition continue to include the United States, China, and Germany. In 2023, twenty-five of the top 30 nations were high-income countries, alongside only four upper-middle-income nations (China, Mexico, Thailand, and Turkey) and a single lower-middle-income nation (India, at rank 20 globally). Only three of the eight regional groupings show an increase in EDI compared to pre-pandemic readings (Western Europe, East Asia Pacific and South Asia). It is, however, important to highlight that while EDI and GDP per capita are generally positively correlated, high-income countries, particularly oil dependent economies, do not always have high economic diversification scores.

In 2024, the Global EDI report introduced new digital trade augmented index (the ‘EDI+’). In the post-pandemic years, digitalisation continues to play an important role in increasing economic diversification while also enabling emerging and developing nations to catch up. The inclusion of digital indicators in the EDI shows that many developing nations are diversifying into the digital space and catching up with more advanced economies. this progress is dependent on factors such as infrastructure availability, regulatory support and the presence of a skilled workforce among others. The 2025 edition confirms that multiple countries in the top quintile of the EDI rise even higher with the inclusion of the digital indicators within the trade sub-index (i.e. trade+ sub-index). Over two-thirds of the nations’ show greater improvements in the trade+ sub-index (comparing 2023 versus 2010) than in the overall EDI+ scores. On the other hand, the lower income groups have yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels, in either EDI or EDI+ scores. This underscores the challenge of achieving recovery without substantial investment in digital infrastructure and relevant enablers. The performance of EDI+ is in line with other digital indices, with the scores showing a positive correlation.

Insights from the latest EDI scores point to a few policy directions. Commodity producing nations need to consider three key factors while deciding on economic policy: (a) the implications of climate change will have an impact on commodities production and extraction; (b) how energy transition is affecting the demand for commodities, including fuel and metals; (c) the continued risks from geopolitical tensions and trade fragmentation, particularly for low-income and emerging market countries that depend on commodities, which may potentially leading to long-term output losses.

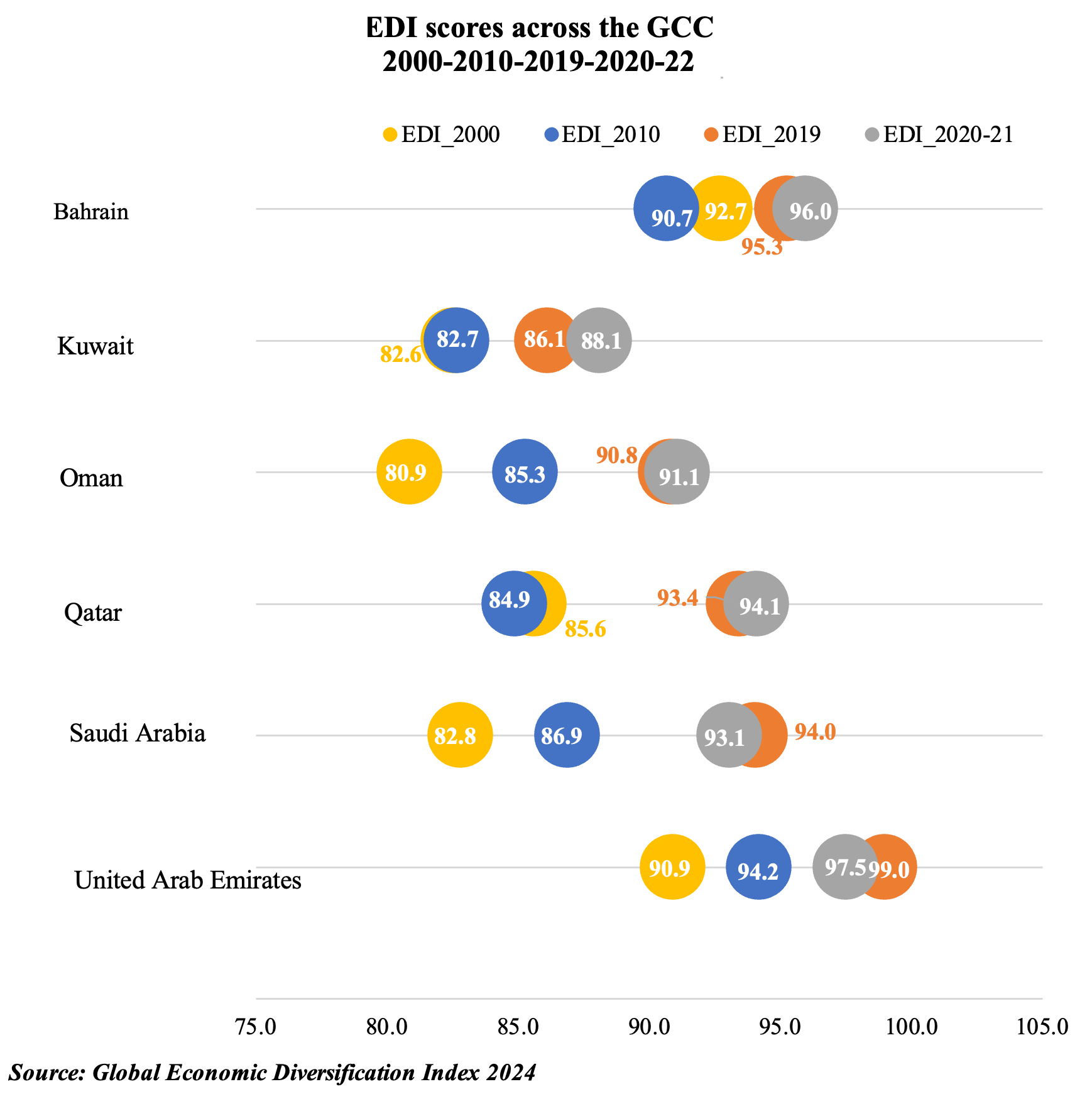

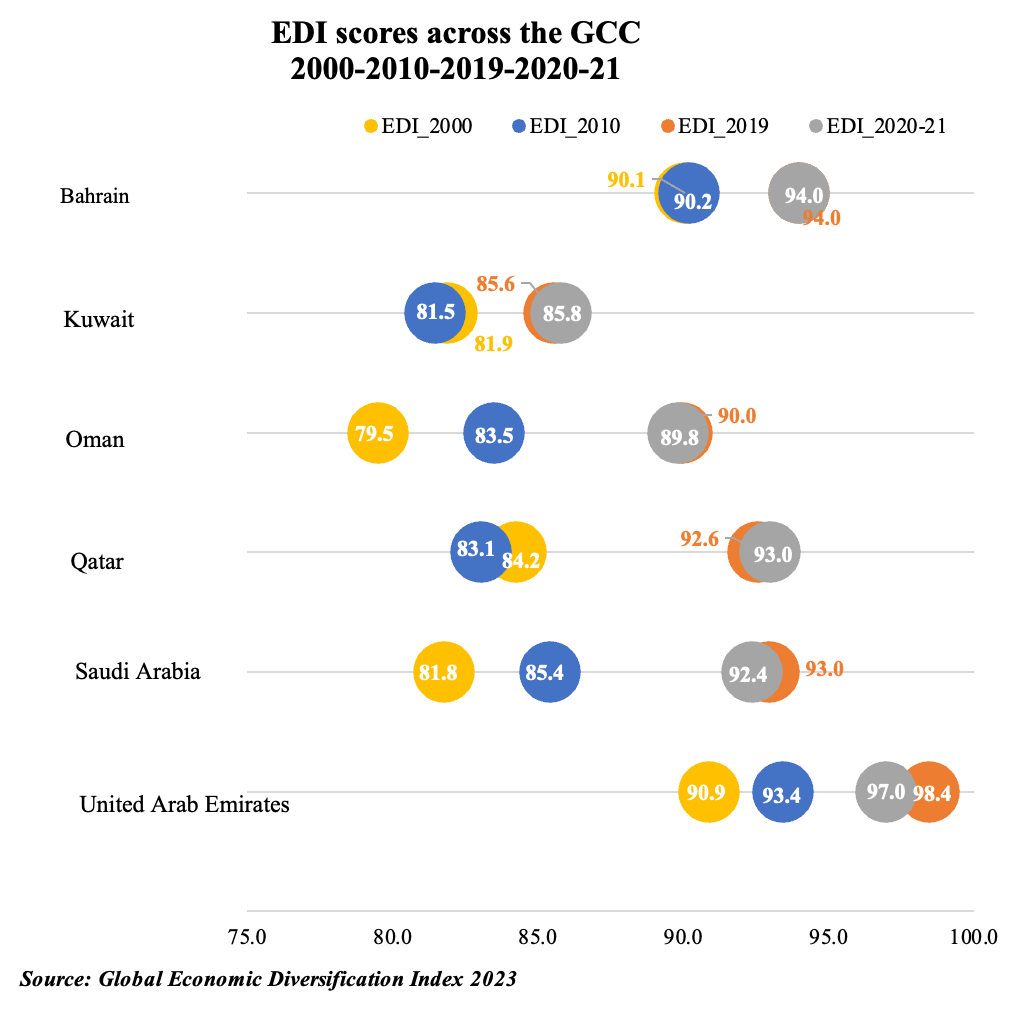

In this EDI edition, 40 countries in the index, nearly 35 percent of the countries covered, are commodity exporters, and within that subset, close to 50 percent of the commodity dependent nations are reliant on fuels. While the more diversified Mexico and Malaysia retain top rankings, given the dynamic nature of diversification, other countries are also undertaking transformational policies: notable cases in 2023 compared to 2000 include Saudi Arabia (up more than 30 ranks), UAE (+24 ranks), Kazakhstan (+17 ranks), Qatar (+12 ranks) and Oman (+10 ranks).Low to middle-income nations such as Angola, Congo and Nigeria remain consistently within the lowest quartile (with common characteristics such as poor governance scores and/ or being politically unstable) along with upper middle-income Azerbaijan. Among the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, Bahrain and the UAE have both scored highly in the output sub-index in recent years, while the UAE outperformed in the trade sub-index. Kuwait lags its peers in all sub-indices, making it the lowest scoring among the GCC countries.

Today, the world faces heightening environmental concerns exacerbating social inequalities and economic instability. The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2025 underscores the urgent need to address these environmental concerns, with “biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse” ranked by respondents as the second-most concerning risk over the next decade. Climate change is forcing nations to hasten low-carbon energy transition plans and policies and consumers to make gradual behavioural shifts away from fossil fuels. Geopolitical forces also reconfiguring the global energy map. Even as the GCC countries emerge as “Middle Powers” in a globally fragmented world, its member states are stand out as energy powerhouses in both fossil fuels and renewable energy amidst global fragmentation.

negative impact on performance but also the divergent paces of recovery. However, both the MENA and Eastern Europe & Central Asia regions reported a slight improvement in the 2020-2022 period versus pre-pandemic scores: these nations were all fuel exporters (i.e. not exporters of any other commodities). The report also finds that countries that reduced (increased) the share of resource rents have seen an increase (decline) in EDI scores, but the relation is one of correlation and not causation. Among the GCC, UAE and Bahrain have higher EDI scores compared to their peers, while Saudi Arabia and Oman have both gained over 10-points in 2020-2022 compared to their EDI score in 2000. Improvements in GCC scores have resulted from the implementation of reforms at a much more aggressive pace after the pandemic – including incentives to invest in new tech sectors, plans to broaden tax bases, trade liberalisation through free trade agreements and improvements to regulatory and business environment among others facilitating rights of establishment and labour mobility – that support diversification efforts and provide long-term economic resilience.

negative impact on performance but also the divergent paces of recovery. However, both the MENA and Eastern Europe & Central Asia regions reported a slight improvement in the 2020-2022 period versus pre-pandemic scores: these nations were all fuel exporters (i.e. not exporters of any other commodities). The report also finds that countries that reduced (increased) the share of resource rents have seen an increase (decline) in EDI scores, but the relation is one of correlation and not causation. Among the GCC, UAE and Bahrain have higher EDI scores compared to their peers, while Saudi Arabia and Oman have both gained over 10-points in 2020-2022 compared to their EDI score in 2000. Improvements in GCC scores have resulted from the implementation of reforms at a much more aggressive pace after the pandemic – including incentives to invest in new tech sectors, plans to broaden tax bases, trade liberalisation through free trade agreements and improvements to regulatory and business environment among others facilitating rights of establishment and labour mobility – that support diversification efforts and provide long-term economic resilience.

The MENA region has lagged behind its regional peers with respect to diversification yet it has caught up relatively fast. This has been supported by diversification strategies introduced by many oil-producing nations in recent years, including the introduction of non-oil taxes (excise, customs and value added taxes to name a few), alongside various liberalisation measures ranging from rights to establishment to trade facilitation measures, and improvements to hard and soft infrastructure.For resource-dependent countries, economic diversification (activity, trade and government revenue) is a strategic imperative given their demographics and job creation requirements, as well as their need to achieve sustainable development and to mitigate the macroeconomic risks of volatile commodity prices and markets. The Global EDI aims to provide guidance for countries, policy makers and analysts to design successful diversification strategies and policies, turning resource rents into an engine of growth rather than a barrier to economic development and thereby avoiding the “resource curse”.

The MENA region has lagged behind its regional peers with respect to diversification yet it has caught up relatively fast. This has been supported by diversification strategies introduced by many oil-producing nations in recent years, including the introduction of non-oil taxes (excise, customs and value added taxes to name a few), alongside various liberalisation measures ranging from rights to establishment to trade facilitation measures, and improvements to hard and soft infrastructure.For resource-dependent countries, economic diversification (activity, trade and government revenue) is a strategic imperative given their demographics and job creation requirements, as well as their need to achieve sustainable development and to mitigate the macroeconomic risks of volatile commodity prices and markets. The Global EDI aims to provide guidance for countries, policy makers and analysts to design successful diversification strategies and policies, turning resource rents into an engine of growth rather than a barrier to economic development and thereby avoiding the “resource curse”.