The article titled “Capital Controls and the Stabilization of the Lebanese Economy”, written by A Citizens’ Initiative for Lebanon was published on 5th January, 2020 in An Nahar and is also posted below.

This note is the latest in a series of analysis by an independent group of citizens who met in their personal capacity in December 2019 to discuss the broad contours of Lebanon’s financial crisis and ways forward.

Capital Controls [1] and the Stabilization of the Lebanese Economy

Summary:

In mid-October 2019, Lebanese banks shut down their branches, imposed informal capital controls and blocked depositors’ access to their deposits. These informal capital controls are unprecedented in Lebanese banking history and are not based on legal grounds. To make matters worse, they have been applied without any transparency and in an arbitrary manner. In line with our 10-point action plan to avoid a lost decade, Lebanon urgently needs to replace these informal controls with formal (i.e., based on laws and regulations), focused and effective capital controls that are an integral part of a macroeconomic comprehensive program for monetary and financial stabilization and economic recovery. Well-designed capital controls are essential in slowing down the outflow of capital and stabilizing Lebanon’s external finances until confidence is restored in the Lebanese banking system and economy.

What are capital controls?

Formal Capital controls are lawful restrictions placed by government authorities on the flow of capital, i.e. on foreign currency transactions. These restrictions are designed by governments, implemented by banks and financial institutions and are typically enforced by a central bank.

Capital controls can take many forms outright prohibition of any international transaction or, alternatively, any international transaction above a certain threshold; restriction depending on the type of the transaction debt vs equity investments, short term vs long term, or capital account versus current account. Iceland, for example, restricted capital account transactions in 2008 but allowed current account transactions in other words, no restrictions were placed on imports taxation of international transactions and, finally, requiring licenses or approvals for certain international transactions such as payments for imports of inputs to industries and other economic activity.

The type of capital controls that will be required in Lebanon will vary depending on the program for monetary and financial stabilization and economic recovery, and more specifically, the foreign exchange regime.

Why are capital controls required in Lebanon?

Capital controls are needed to slow down the outflow of capital from Lebanon. The key reasons for imposing capital controls are:

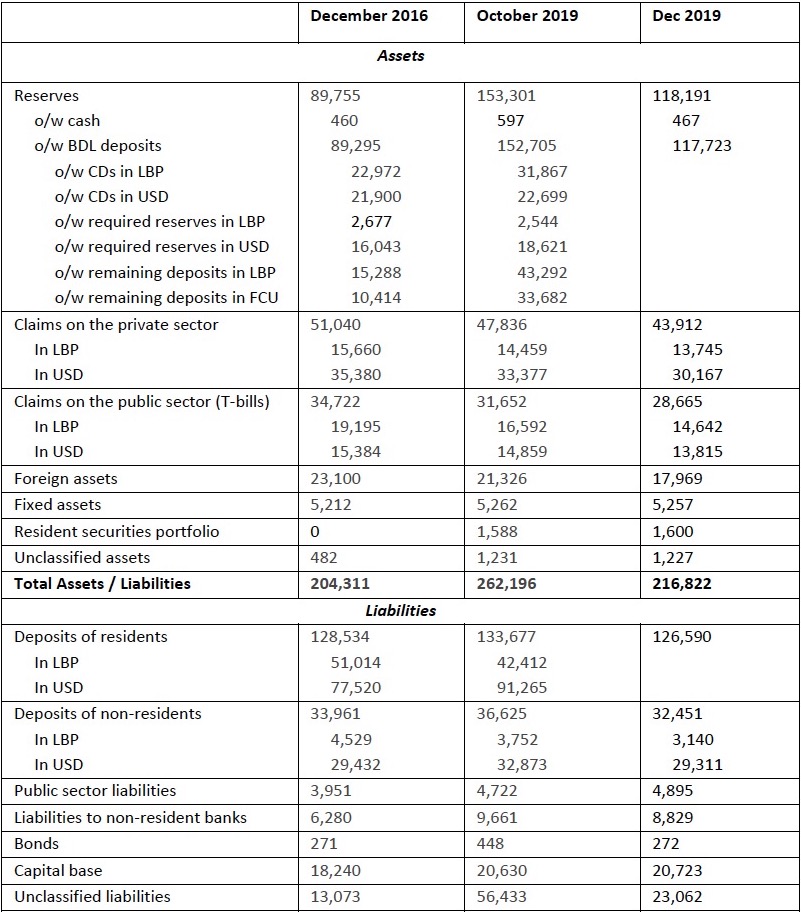

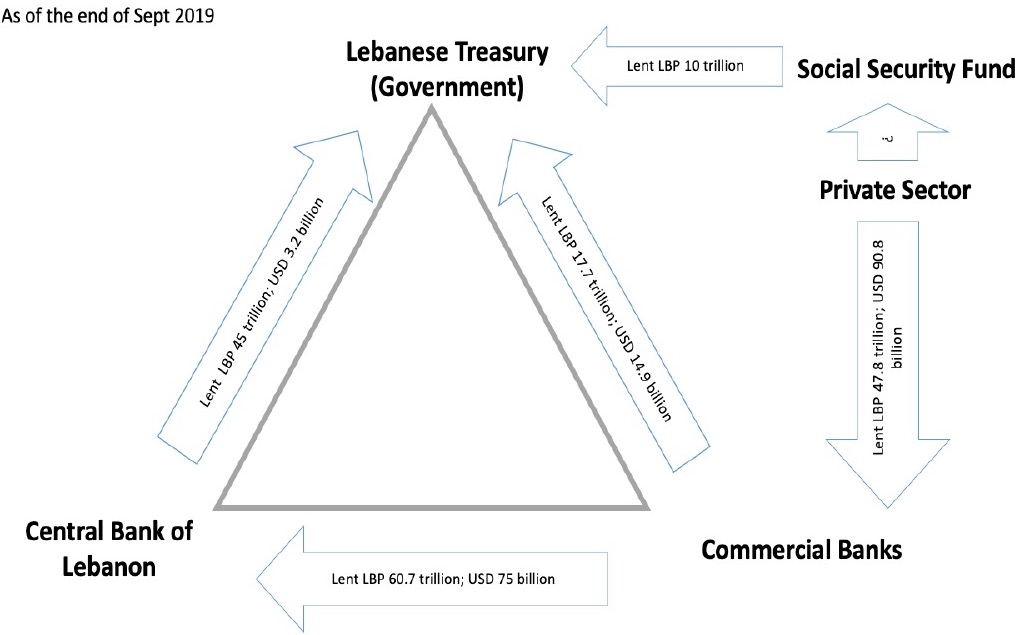

- the large net negative foreign currency position (net reserves) of the Central Bank of Lebanon [2]. BDL is not in a position to meet the banks’ foreign exchange requirements.

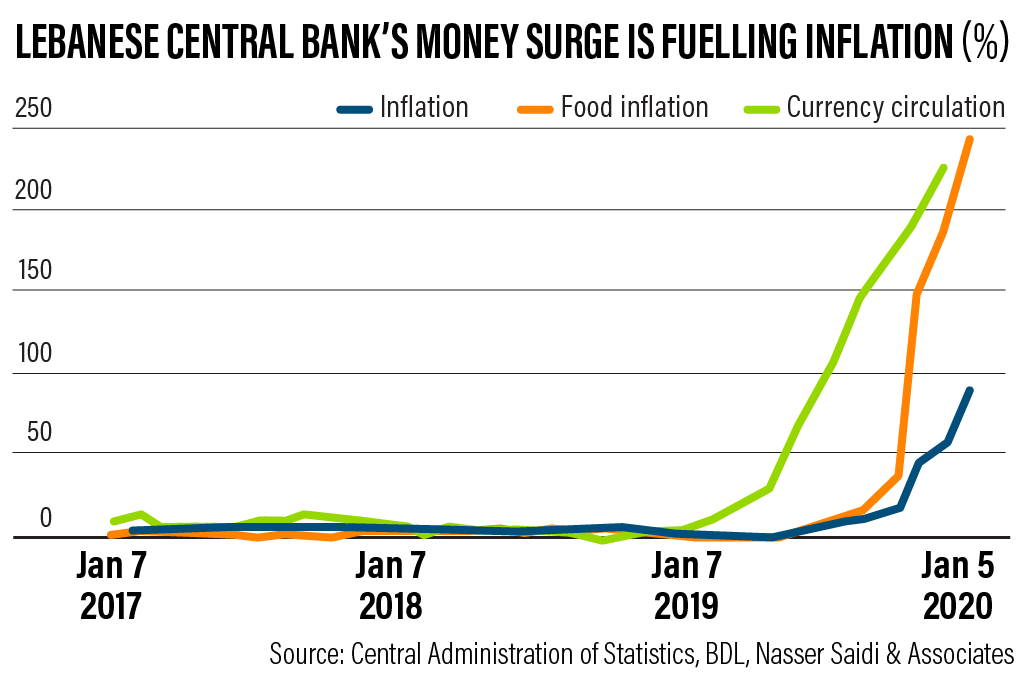

- the need to limit the rapid decline in foreign exchange reserves and, therefore, the loss of confidence in the ability of BDL in maintaining the exchange rate peg and the depreciation of the LL in the parallel market.

Given the large exposure of Lebanese banks to BDL, it will be very difficult to restore confidence in the banking system and stem the outflow of deposits without capital controls.

There are currently over $170 billion in deposits in the Lebanese banking industry. Given the lack of confidence in Lebanon’s economy and financial system and given the lack of trust in the ability of the political establishment to lead the country out of the financial crisis, most deposits will likely be transferred out of the Lebanese Lira (out of the banking system, and out of Lebanon at the earliest opportunity. A panic run on the banks will put many banks at risk of failure and depositors will lose their deposits. Furthermore, the LL is likely to depreciate even further below the current unofficial market rate which is itself more than 40% lower than the LL 1505-1515/US$ official BDL rate.

The informal capital controls that were introduced in October 2019 are unfair to depositors. Well-designed capital controls can 1) limit rapid currency fluctuations in Lebanon’s case, to slow down the rapid depreciation of the LL, and 2) contain panic runs on banks until confidence is restored if they are part of a credible and comprehensive macroeconomic fiscal financial stabilization program.

What do capital controls mean in the Lebanese context?

Lebanese banks have put in place informal capital controls since mid-October 2019. The alleged rationale is to avoid a panic run on the banks which could result in banks seeing all their deposits withdrawn at the same time. Despite the informal capital controls, about US$1.6 billion were transferred between October 17, 2019, and the end of 2019 It has been reported that these transfers were carried out when banks were closed to the public. This has fueled widespread anger and in some cases, violence against the banks.

The informal capital controls have been implemented in an arbitrary manner, with each bank and in some cases, each bank manager deciding how much foreign currency to allow each depositor to withdraw on a weekly or monthly basis or which transactions to honour. To date, there have been no less than three court rulings in favor of depositors who challenged the legality of the banks’ sequestration of their deposits.

Formal capital controls should 1) replace the informal controls with legally sound, transparent, fairly and uniformly applied controls; 2) give time for a credible and comprehensive stabilization program to restore trust in the financial and economic system; and 3) lead to the phasing out of the multi-tier exchange rate system in line with the stabilization program.

How can capital controls be introduced in Lebanon?

Capital controls (قيود على رأس المال) in Lebanon can only be imposed by law and even then, for a finite period of time. Capital controls require either an act of Parliament or, if a government is so empowered, by legislative decree (مراسيم ت رشيعية). The legislation needs to identify the types of controls that should be introduced for how long, and how these controls are to be enforced by the monetary and banking authorities and regulators. Legislation should define the principles and the broad parameters for banking and capital controls ensure transparency and good governance and provide adequate checks and balances to avoid abuse and additional market distortions.

The specifics of capital controls should be set by government policy and BDL regulations. Capital controls should be embedded in the government’s comprehensive program for macroeconomic and monetary reforms, financial stabilization and economic recovery. They should not be a substitute for stabilization nor a cause for delaying fiscal, structural, and financial reforms.

Capital controls are too important to be left to BDL and the banking system to decide. They are an instrument, albeit temporary, of economic policy and they have a material impact on depositors. To be effective, they must have a solid legal basis including constitutional legitimacy and have the necessary political backing for the monetary and banking authorities to enforce these controls.

There are those who have made the case that existing legislation the 1963 Money and Credit Code and its amendments, gives the Governor of BDL wide powers that could be used to introduce capital controls. There are three problems with this argument. First, even by the admission of its proponents, there is no clear mandate for BDL to impose capital controls and, were it to do so, these will be easy targets for legal challenges. Second, such an expansive view of the powers of BDL will set a bad precedent including raising issues of accountability and, therefore, undermine confidence in the banking industry for decades to come. Third, introducing capital controls through BDL circulars does not relieve the government and the political parties that are represented in it from the responsibility of backing formal capital controls.

There is no substitute for legislation whether through Parliament or by legislative decree to ensure that capital controls adhere to the following principles:

- Appropriate: The controls should be bound by legislation to deliver the appropriate level of restrictions on capital account transactions. Controls are more effective when they are simple, wide reaching, and do not leave room for arbitrary decision making:

- Controls should not affect foreign exchange accounts that are below a certain threshold which would not materially affect the country’s overall external balances. Account holders should be allowed to transfer a maximum amount every year from LL to US$ or from a resident account to a non-resident account.

- Controls should not affect capital that reaches Lebanese banks after a certain date (what is commonly referred to as “fresh money”).

- The financing of current account transactions should be allowed while imbalances in the current account should be addressed via other measures (e. import duties).

- Fair: Controls should be applied fairly to all citizens and all depositors should have access to their deposits on the same terms and conditions. Decisions r elated to the implementation of controls should be subject to review (by the enforcing authority) and appeal (through the judicial system).

- Limited: Legislation should place a time limit a sunset clause on all controls. Previous experience shows that countries have kept controls in place for a few years. How long the controls will be needed in Lebanon will depend on the government’s stabilization program.

- Transparent: BDL and the Minister of Finance should present joint report s to the Council of Ministers every six months justifying and providing evidence of the effectiveness and the need for the continuation of controls. Parliament, too, should review these reports make them public and keep the pressure on the Council of Ministers to hasten the lifting of controls.

Are capital controls “bad”?

Capital controls lead to inefficient capital deployment, market distortions, slow growth, slow investment in socially desirable sectors such as education and healthcare, and, most importantly, scare away non-resident capital including FDI which is essential for productive investment and job creation. Capital controls can also cause a lot of damage to the perception of risk associated with that country. Once capital controls are used, it can take years for a country to outlive the perception that it is likely to use these controls again. Without countervailing measures, the country risk rating will be negatively affected for years to come.

Capital controls create incentives for evading enforcement and, therefore, present opportunities for abuse and corruption. The more latitude government and BDL officials have in determining when and how to apply the controls, the weaker the oversight functions and, hence, the easier it will be to evade the controls. The experience of countries in licensing access to FX which is not recommended for Lebanon, shows how pervasive corruption can become. Any application of controls should be accompanied by appropriate measures for the accountability of BDL and regulators for their implementation of the controls.

Despite all this, capital controls are urgently required. Introducing capital controls in Lebanon is not to be taken lightly. Some objections have been raised to capital controls on the ground that they would irreparably damage the reputation of Lebanon’s banking industry. Others would argue that the damage has already been done by the unjustified bank closures, informal controls and payment restrictions and that these should urgently be revised to be fit for purpose and regularized. We are squarely in the latter camp.

Capital controls are needed in Lebanon as a tool of last resort and not an instrument of industrial policy:

- They are necessary to stabilize the economy and manage, to the extent possible, the LL/US$ exchange rate in order to avoid a crash landing of the LL which will have devastating effects on the vast majority of the Lebanese population, over and above the 40% effective depreciation of the LL on the parallel market. It is, indeed, a stopgap measure and not a silver bullet, nor an alternative to genuine economic reforms;

- They are necessary to buy time to provide for an orderly restructuring of the financial sector;

- They allow for the reduction of interest rates which can help kick start investments and start generating growth.

In 1998, Paul Krugman wrote a letter to the Malaysian Prime Minister, in which he encouraged him to introduce capital controls. In it, Krugman wrote: “Currency controls are a risky, stopgap measure, but some gaps desperately need to be stopped.” [3] Malaysia introduced capital controls as part of a comprehensive stabilization program which resulted in a shallower and shorter recession, and a faster recovery than other East Asian economies.

Are International Financial Institutions opposed to capital controls?

The short answer is “No”. The IMF has, in recent years, been more flexible about capital controls as long as these are not meant to delay financial reforms. [4] IMF programs have been accompanied by capital controls in many countries, most notably in Iceland. The IMF Articles of Agreement rule out capital controls, but they carve out an exception.[5]

The IMF recognizes that formal capital controls may be needed in some very specific circumstances, such as the risk of drastic and rapid depreciation of the currency, the risk of depletion of foreign reserves and the onset of a crisis in the banking industry. However, IMF requires, as most Lebanese would, that capital controls be accompanied by a comprehensive program for economic, fiscal, structural and financial sector reforms.

In summary, Lebanon urgently needs to replace the informal and haphazard capital controls with formal capital controls to ensure fair, transparent, and regulated flows of capital and depositors’ access to their bank deposits. Capital controls, if introduced for a limited period of time and as part of a broader program for financial stabilization and economic recovery, do not mean the end of the liberal economic order n or the demise of the Lebanese banking and financial industry. Quite the contrary, they could be an integral part of a much needed program of economic, fiscal structural, and financial sector reforms that put s the economy back on the path to recovery.

Signatories (in their personal capacity)

Firas Abi-Nassif, Amer Bisat, Henri Chaoul, Ishac Diwan, Saeb El Zein, Nabil Fahed, Philippe Jabre, Sami Nader, May Nasrallah, Paul Raphael, Nasser Saidi, Kamal Shehadi, and Maha Yahya

Institutional Endorsements

LIFE

Kulluna Irada

[1] We will use the term capital controls to refer to formal capital and banking controls in the rest of this paper

[2] Hereafter referred to as BDL, the acronym for Banque du Liban

[3] Paul Krugman, “Free Advice: A Letter to Malaysia’s Prime Minister,” Fortune September 28, 1998.

[4] IMF, The Liberalization and Management of Capital Flows: An Institutional View November 14, 2012

[5] Article XIV, Section 2, of the IMF Articles of Agreement makes an exception for transitional arrangements: “A member that has notified the Fund that it intends to avail itself of transitional arrangements under this provision may, notwithstanding the provisions of any other articles of this Agreement, maintain and adapt to changing circumstances the restrictions on payments and transfers for current international transactions that were in effect on the date on which it became a member (…) In particular, members shall withdraw restrictions maintained under this Section as soon as they are satisfied that they will be able, in the absence of such restrictions, to settle their balance of payments in a manner which will not unduly encumber their access to the general resources of the Fund.”